The case of the Slovak minority in Poland

Polish language policy towards minority languages

This paper looks into the Polish language policy towards minority languages through the case of the Slovak minority in Poland by analyzing strategies that are used for language maintenance and development in the fields of education and the media.

Slovaks in Poland: a national minority without moving

Being a migrant is nothing exceptional in the contemporary world. While some people migrate within their home country, others migrate internationally; for the most part, they are members of a national, ethnic, or language minority in the place where they live. However, there are occasional cases of people who become a national minority without even leaving their homes. This is what happened to Slovaks living on the borders of Poland and Slovakia. In the 20th century, the border between Poland and Czechoslovakia, or the Slovak State, was modified several times. This meant that people were suddenly living in a different country without actually having moved .

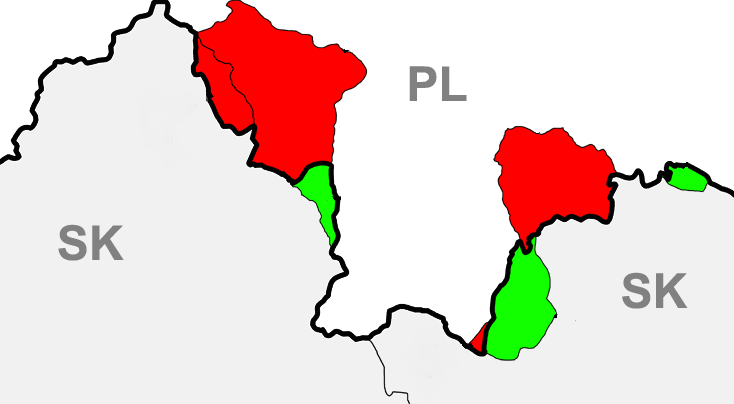

Border dispute: Poland got the red areas while Czechoslovakia the green ones.

Although exposed to serious polonization throughout the years, the Slovaks from the area have been managing to maintain their Slovak identity, partly due to use of the Slovak language.

Minorities in Poland

Poland is one of the most homogenous countries in Europe, when considering nationality, which is viewed as a sense of belonging to a certain national or ethnic group (McCrone and Kiely, 2000). In the latest census, which took place in 2011, 96.74 per cent of the population claimed Polish nationality, 1.23 per cent other than Polish nationality and the nationality of 2.03 per cent could not be determined. The largest national minorities were Germans, Belarussians, and Ukrainians (Rykała, 2014). One of the recognized minorities is also Slovak, the past of which is complicated. In order to understand the current situation of the Slovak-national minority in Poland, it is necessary to describe how it came into existence and what the situation was like throughout the 20th century.

History of the Polish-Slovak borderland

After the end of World War I, the borders of European countries were changing. Poland, quite surprisingly, made claims to territories that were south of its borders at that time (Majeriková-Molitoris, 2013a): the area of the newly established Czechoslovakia. It also covered part of the area's present-state Slovakia. The argument of Poland, on the basis of which they claimed the border areas, was so-called ‘ethnographic theory’ (ibid). It was based on “the hypothesis formulated at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries by Polish intellectuals about linguistic similarity between the Hungarian Gorals with Polish, from which they inferred their Polish identity, which was needed, in their opinion, only to be ‘rekindled’” (ibid) (note 1).

In addition to the claims that Poland made about the Upper Orava and the Northern Spiš, which were south of Polish borders, it also claimed the Těšín area in what is now the Czech Republic. The foreign ministers of Czechoslovakia and Poland decided to leave the decision to the Great Committee of the Paris Peace Conference, which then delegated the Council of Ambassadors to settle the dispute (Andráš, 2001). The Těšín area was divided between Poland and Czechoslovakia, but the Upper Orava and the Northern Spiš was lost to Poland (ibid). The lost area was comprised of 27 villages.

In the period between the two world wars, inhabitants of these communities encountered repression and experienced “absolute polonization that was happening (...) in the name of awakening ‘Polishness’” (Majeriková-Molitoris, 2013a, p. 21). People living in these areas felt to be Slovaks. “Gorals are ethnically one whole, they speak say the transitional Polish-Slovak dialect, while their national consciousness was developing over the centuries by demarcation of the state border of the Hungarian Empire and Poland. On the Polish (...) side, it is the Polish consciousness, on the Hungarian side Slovak.” (Andráš, 2001) (note 2, note 3) Nevertheless, in the interwar period, they were not recognized as a national minority and therefore, had no rights. Slovak schools were shut down in the region. Part of the population even decided to move out to the territory of Czechoslovakia (Majeriková-Molitoris, 2013a).

In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, Poland obtained other territories (Andráš, 2001). Another change of borders between Czechoslovakia and Poland took place at the beginning of World War II. The Slovak State, which was formed under the Nazi rule in 1939 and lasted till the end of the WW II, was formed. After the defeat of Poland by Nazi Germany, in which the Slovak army took part on the German side, the border from 1918 was restored and the territories Slovakia lost in 1920 and 1938 were returned (ibid). During the existence of the Slovak State, the inhabitants of Northern Spiš and Upper Orava identified with the new state (Majeriková-Molitoris, 2013a, p. 22). These people felt to be Slovaks and spoke Slovak.

In 1945, after the end of WW II, significant changes took place again in Europe, and Czechoslovakia was restored. Again, Poland voiced claims to the territory of Northern Spiš and Upper Orava, which they had in the years 1920 to 1939. The population of the area actively resisted this annexation (Andráš, 2001):

“After the liberation by the Soviet army, the national committees held a plebiscite, according to which 98 percent of the population claimed Slovak nationality. Therefore, these authorities were persuading leaders of the Soviet Army that this territory belonged to Czechoslovakia. But the Czechoslovak government (...) decided to return these regions to Poland…” (ibid)

Residents of these areas, which were returned to Poland again, were persecuted and still were not considered as national minorities. Furthermore, Slovak schools did not operate in the areas, and Slovak priests were expelled from parishes. Gradually, the situation began to change, especially through the activities of the Czechoslovak diplomacy led by the consul Matej Andráš. “Based on the principle of reciprocity, it was even considered that if the Poles did not reopen Slovak schools, it would be an argument for closing Polish schools at the Těšín region. Therefore, in the end, the Polish side began to consider reestablishment of the Slovak schooling” (Majeriková-Molitoris, 2013a, p. 131). In 1947, the Czechoslovak-Polish treaty of friendship and mutual assistance was signed, which included the principle of reciprocity and consequently Slovak-medium schools started to open. However, most of such schools were closed down in the 1960s. The main reason was that the Czechoslovak diplomacy in Poland paid less and less attention to the issue (ibid).

The main tool of polonization of the Slovak national minority was the church. “Usage of the Slovak language in the church essentially depended on the goodwill of a particular priest, which led to continual disputes and controversies” (ibid, p. 178). In 1949, the establishment of an organization of the Slovaks in Poland was approved, which, after a few variations, still operates (ibid, p. 180). Its current name is the Association of Slovaks in Poland (Towarzystwo Słowaków w Polsce; hereafter referred to as the Association).

Current state of the Slovak minority in Poland

The Slovak national minority is, therefore, historical in the area of today’s Poland. In the 2011 census, 3,241 people claimed Slovak nationality. Out of those, 2,739 were autochthonous residents, who have Polish citizenship (Majeriková-Molitoris, 2013b). More than half of these people live in Malopolskie voivodeship (note 4), which also encompasses the areas of Upper Orava and Norther Spiš (ibid). However, Slovak officials estimate the number of Slovaks in Poland to be up to 25,000 (The Office for Slovaks Living Abroad, 2012) and Poland estimated the total number of addressees of “projects for maintaining the cultural identity of national and ethnic minorities (...) (including preserving minority and regional languages)” (Republic of Poland, 2015, p. 20) to 24,900 in 2013.

There is a considerable discrepancy between the actual number from the census and the estimates. This is caused by assimilation, which can be defined as “attenuation of distinctions based on ethnic origin” (Alba and Nee, 2003, p. 30). According to Moskal (2004), the number of members of historical minorities living on the territory of Poland, which are Belorussians, Ukrainians, Ruthenians, Germans, Roma, Slovaks and Russian, is decreasing and these people are being assimilated. Rykała (2014) sees the results of the 2011 census as a confirmation of the thesis that “minorities underwent the process of gradual assimilation throughout the whole post-war period” (ibid, p. 149). The Office for Slovaks Living Abroad (2012) dubs this assimilation as “rather intense”, the main reasons for which are “language, cultural, value and religious compatibility” (ibid) (note 5). This compatibility may make the minority less aware of the assimilation process (ibid). However, awareness of this process may help in establishing the goals of the Association of Slovaks in Poland.

Although low in numbers, there are members of many national and ethnic minorities living in Poland, who also have their own languages. These languages are national-minority languages, such as Slovak or Belorussian; a regional minority language called Kashubian; ethnic minority languages, such as Lemko and Romani; and finally non-territorial languages, such as Hebrew or Yiddish (Council of Europe, 2009). These minority languages are, apart from the national language, subjects of the Polish language policy.

Language policy in Poland

Language policy refers to “a body of ideas, laws, regulations, rules and practices intended to achieve the planned language change in a society, group or system” (Kaplan & Baldauf, 1997, p. xi). The language policy of Poland is affected by the country’s past, having “historical experience that foreign rulers and occupants repressed the Polish language and endeavoured to denationalise the Polish nation” (The Parliament of the Republic of Poland, 1999).

Poland has several documents regarding language policy. The national language of Poland is Polish, as stated in the Constitution of the Republic of Poland, which came into force in 1997 (Moskal, 2004). The constitution also guarantees minority rights to Polish citizens who belong to the national or ethnic minorities. They have “the freedom to maintain and develop their own language, to maintain customs and traditions, and to develop their own culture” (The Constitution of the Republic of Poland, 1997) and can “establish educational, cultural and religious institutions designed to protect their identity” (ibid).

Poland also has The Act on the Polish Language from 1999, which regards the protection of the Polish language. However, it also states that it is not contradictory to “legal regulations about the rights of national minorities and ethnical groups” (The Parliament of the Republic of Poland, 1999). In 2005, the Polish government adopted The Regional Language, National and Ethnic Minorities Act, which

“regulates issues connected with the preservation and development of the cultural identity of national and ethnic minorities, the preservation and development of the regional language, as well as ways to implement the principle of equal treatment irrespective of a person’s ethnic origin.” (The Parliament of the Republic of Poland, 2005)

Learning a minority language as a mother tongue is guaranteed by the Decree of the Ministry of National Education and Sport from 2002, where such languages are taught at the request of parents or older students themselves (Compendium, 2014). This decree also specifies the number of students required for establishing a class in a minority language, which is seven at primary and fourteen at secondary level (ibid).

Another document that regards minority languages in Poland is the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (henceforth referred to as ‘the Charter’), which was signed in 2003 and ratified in 2009. The languages protected by the Charter in Poland are Belorussian, Czech, Hebrew, Yiddish, Karaim, Kashub, Lithuanian, Lemko, German, Armenian, Romani, Russian, Slovak, Tatar and Ukrainian (Council of Europe, 2009).

With the neighbouring states, which are Germany, the former Czech and Slovak Federal Republic, Ukraine, Belorussia and Lithuania, Poland has signed bilateral treaties, “which further guarantee the protection of the rights of national minorities” (Moskal, 2004, p.9). The full name of this treaty in the case of Slovakia is ‘Agreement between the Government of the Slovak Republic and the Government of the Republic of Poland on cultural, educational and scientific cooperation’, which is based on an original agreement between Czechoslovakia and Poland, was signed in 1991. Article 21 of the treaty is focused on the Slovak minority in Poland and the Polish minority in Slovakia, where it states that the signatories will support these minorities in “development of their language, traditions and national culture” (Government of the Slovak Republic, 1991). Education in the field of Slovak and Polish languages in the respective countries should be available (ibid).

The language policies that Poland has implemented, regarding both Polish and minority languages, can be considered as status-planning policies. This is due to the fact that they are concerned with the position of these languages in the society, where Polish has an unquestionably dominant status. However, the policies are also acquisition-planning, as they largely discuss education and learning of the languages. The main actor in these policies is the Republic of Poland, which is, in most of the cases, also a policymaker. In the case of the Charter, the policymaker would be the Council of Europe. Further actors are members of the recognized minority groups, as well as other countries, which have signed bilateral agreements with Poland.

Although the language policy of Poland towards minority languages aims at their maintenance and development, it can be viewed as a country with a monolingual ideology, where “(o)ne language is recognized as associated with the national identity; others are marginalized” (Spolsky & Shohamy, 2000, p. 28). Therefore, Polish is linguistically hegemonic in Poland. The language policy in Poland can be considered not as specifically enabling a planned language change, but rather as a tool to maintain the status quo. Furthermore, except for the Charter, monitoring tools of the effectiveness of the language policy are unclear. The Charter has a monitoring cycle, in which the authorities of the countries which ratified the document submit a report about the implementation of the undertakings, which is then reviewed by the Committee of Experts that gives recommendations for the following monitoring cycle.

The case of the Slovak minority

Education

Currently, there are no schools at any level which have Slovak as a medium of instruction (Majeriková-Molitors, 2013a). Slovak is taught as a subject, mostly optional, in schools up to lower high school level (note 6), with time commitment of three to four classes per week. On the upper-secondary level, Slovak is supposedly not taught, because “(f)or several years, the Slovak community in Poland has not expressed any interest in continuing of teaching the Slovak language at the level higher than junior high school” (Republic of Poland, 2015, p. 52). Nevertheless, according to the website of the upper secondary school (liceum) in Jablonka, students have the opportunity to study Slovak as a second language after English (Zespół Szkół im. Bohaterów Westerplatte, 2015).

The Polish Ministry of National Education regularly collects data on teaching minority and regional languages in schools (Republic of Poland, 2015). In the school year 2012/2013, there were 202 pupils studying Slovak language, while in 2013/2014, the number was 333 (ibid). Out of these, 181 were children in preschools (ibid). In some villages in Northern Spiš, the share of primary school pupils attending Slovak-language lectures reaches 50 per cent. The data from the school year of 2015/2016 shows that there are 255 students learning Slovak in primary and secondary schools, which is a rise from previous years (Život, 2016).

The right to learn or be educated in a minority language is incorporated within The Regional Language, National and Ethnic Minorities Act (The Parliament of the Republic of Poland, 2005), as well as in the Charter (Council of Europe, 1992). Based on the commitments defined in the Charter in the field of education, Polish authorities have moved towards making pre-school, primary and secondary education available in the minority languages. In the first evaluation report, the Committee of Experts considered these undertakings as not fulfilled for the Slovak language, or for other languages, and “(i)t encouraged the Polish authorities to make available (...) education in these languages” (Council of Europe, 2015, p. 91). However, in the second evaluation report, these undertakings were still considered as not fulfilled for Slovak. Furthermore, it urged “the Polish authorities to develop the teaching of (...) Slovak, (...) as a step that might lead, in the future, to the gradual implementation of the undertakings concerning pre-school, primary and secondary education” (ibid, p. 92). The undertaking regarding technical and professional education, to “include teaching relevant regional or minority languages as an integral part of the curriculum” (Republic of Poland, 2015, p. 43) was also considered as not fulfilled. The Polish authorities claimed that it is not provided “in spite of legal and financial possibilities” (ibid, p. 44).

It can be said that Poland, to some extent, supports the teaching of the Slovak language. However, according to the Charter, its role within preschool, primary and secondary education should not be to respond to the demand, but rather to create an offer of teaching the language. It can be seen that the number of pupils studying the Slovak language rose significantly in one school year, although it may have been caused by a change of the data collection system. Even so, it can be argued that intensive promotion from the side of the Polish authorities could help increase the number of students interested in studying the Slovak language.

The issue is that the general attitude of the Polish towards Slovak may need to change in order to increase the number of students studying the Slovak language. “Nowadays, the situation is such that some parents do not support their children in learning Slovak, one of the reasons is putting certain pressure from the side of the Polish. (...) Because of the Slovak nationality, it is possible that a Slovak person will not be accepted for a vacancy they applied for” (Milová and Zittová, 2014).

In 2011, seven teachers of Slovak in Polish schools discussed problems they faced with the chairman of the The Office for Slovaks Living Abroad (The Office for Slovaks Living Abroad, 2011). The three key problems identified were the decreasing number of students of Slovak, permanent shortage of new Slovak textbooks and the inability of teachers to attend trainings in Slovakia due to problematic cooperation by the schools in which they were employed (ibid). Although the Slovak and Polish ministries of education have a cooperation agreement, the Polish side has not yet signed the supplement which would help with the last two problems mentioned above (Ministry of Education of the Slovak Republic, 2015). Furthermore, support of education of teachers and access to study materials is guaranteed by The Regional Language, National and Ethnic Minorities Act (The Parliament of the Republic of Poland, 2005) and yet, not practiced.

It is evident that the language policy of Poland is inextricably linked with educational, as well as national policy.

In order to understand the language policy, it is essential to look at Poland as an ethnically homogenous state with a clear mission to have Polish as a national language. While languages of the minorities are officially supported (which is also the case of Slovak), in reality, speakers or potential speakers of the language are exposed to the assimilation pressure. Furthermore, support for teaching and learning the language is limited, which manifests itself in subtle ways, such as limiting the options of teachers to extend their education or missing textbooks.

Media

One of the tools which can contribute to language maintenance is the media. Although the term ‘media’ is very broad in the contemporary world, in the context of this paper, it is used to refer to broadcast media, which are radio and television, print media, and also information portals online. Support, or on the other hand, insufficient support of the media in a minority language can be a part of the language policy of a certain country. Whereas the media may seem like effective tools in language maintenance, as they bring languages to the people, the issue is more complex than that. Cormack (2007) argues that

“(m)edia seem most likely to encourage language use when they are strongly participative, strongly linked to communities (whether territorial or diasporic) of language speakers, and when they can give people a reason for adopting, or asserting, the identity of being a minority language speaker.” (p. 66)

Furthermore, he also states that at present, there is not enough knowledge on the relationship of the media and language maintenance in bilingual situations.

Despite these doubts about the effectiveness of the media in language maintenance, the encouragement of media outputs in minority languages is part of the Polish language policy towards these languages. The media can be seen as part of culture, which Poland guarantees the minorities the right to develop. In the Agreement between the Government of the Slovak Republic and the Government of the Republic of Poland on cultural, educational and scientific cooperation (1991), it is stated that the parties will support cooperation between the public radio and television broadcasters, based on agreements among these institutions. However, broadcasting of the state-owned public Slovak Television is not widespread in Poland, although “(f)rom the side of Slovaks, there is a clear interest in broadcasting of the Slovak Television abroad, which would enable hearing Slovak daily” (Kokaisl and col., 2014, p. 37).

The media is covered in the Charter under Article 11. Poland chose several provisions which, in short, say that the country should encourage and/or facilitate the availability of radio and television channels and broadcasts in the minority languages, and do the same with the regular publication of newspaper articles. Furthermore, Polish authorities emphasize that “the Minister of Administration and Digitization shall transfer funds to protect, to preserve and develop the cultural identity of the minorities and to preserve and develop the regional languages, including supporting television programs in minority and regional languages” (Republic of Poland, 2015). In addition to this, The Regional Language, National and Ethnic Minorities Act (The Parliament of the Republic of Poland, 2005) states that “(p)ublic authorities are obliged to take adequate measures” in “(s)upporting the television programmes and radio broadcasts produced by minorities” (ibid).

As of 2015, there were no public or private radio or television channels, programmes or broadcasts in Slovak, as reported by the Committee of Experts (Council of Europe, 2015). In its second report, Poland stated that from 2011 to 2014, there were no applications for any kind of broadcasts in Slovak (Republic of Poland, 2015). The only languages for which Poland's Ministry of Administration and Digitization received applications for projects were German and Kashubian (ibid).

Milová and Zittová (2014) state that the non-existence of broadcasts in the case of the Slovak minority takes place “despite the efforts of the Association of Slovaks in Poland” (p. 58). These efforts can be seen from a television broadcast Informátor slovenský [The Slovak Informant] produced by the Association, which was cancelled due to the lack of finances (Kokaisl and col., 2014). Therefore, there is a discrepancy between claimed financial support by the Polish government and the lack of projects, as well as ceasing the broadcast in Slovak. The question is, does the Polish side actively encourage and support these broadcasts among the members of the minority groups, as implied in their language policy? Also, there have been no radio shows in Slovak in Poland, although in the area of radio broadcasting, the situation seems to be more favorable towards the minority languages in general.

What the problem regarding the situation of radio and television broadcasts can be, is that Poland is a relatively recent signatory of the Charter and therefore, has not had enough time to implement all the undertakings yet. In the last evaluation of the Committee, it urges the Polish authorities to mobilize in the field of the media and encourage these broadcasts. However, the results will only be visible in the next monitoring cycle. On the other hand, the Regional Language, National and Ethnic Minorities Act has been in action for more than ten years already, so in this context, the broadcasts can be considered to have been neglected.

It can be argued that in the meantime, “the deficit of radio and television broadcasts is compensated by the internet portal. As a medium of information exchange, it is popular not only among compatriots from Poland, but also from abroad” (The Office for Slovaks Living Abroad: Slovaks Abroad, 2012).

One of the aims of the minority language policy in Poland is to have at least one newspaper issued in each of the minority languages (Council of Europe, 1992). The most important periodical of the Slovak minority in Poland is the magazine Život [Life], which is issued monthly in around 2,300 copies, most of which are sold in the form of subscription (The Office for Slovaks Living Abroad: Slovaks Abroad, 2012). Its producer is the Association and its editorial staff is based in Krakow. This magazine can encourage language maintenance, as it has a strong link to the community and supports a sense of belonging. The Život magazine is financially supported by the Ministry of Administration and Digitization through special-purpose subsidies (The Association of Slovaks in Poland, 2010). In this case, the undertakings of the Polish-language policy can be considered fulfilled, as the magazine is not only issued, but financed via the Polish government.

The policy towards the minority languages in the media in Poland is a language policy. Not only is it a part of language policy documents, but it also aims at supporting language maintenance through the means of various media. However, from researches among the Slovak community in Poland and the reports of the Polish authorities and Council of Europe, the positive results in radio and television broadcasting are not visible. The indications are that this is a consequence of inactivity of the Polish side in promoting the opportunities for funding and other kinds of support.

Better communication, better results?

Language is omnipresent in all areas of life.

Language policy on the state level has to consider various aspects of life where language is present and can be developed, such as education, administration, religion, culture and its different facets. That is why states should create policies which do not contradict each other, but support each other. Poland has a strong nationalist policy, which intertwines with its educational policy, policy towards minorities, as well as language policy.

Poland deals with minority languages through various documents, which are national, such as the Regional Language, National and Ethnic Minorities Act; bilateral, as the Agreement between the Government of the Slovak Republic and the Government of the Republic of Poland on cultural, educational and scientific cooperation; as well as international documents, represented by the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. These policies in general have their individual aims, but what they lack are effective monitoring tools, which would help supervise how the policies are carried out. Poland reports on and gets feedback regarding the fulfillment of its undertakings from the Charter. The usage and effectiveness of monitoring tools is what could be improved in Polish language policy towards minority languages.

Considering that the topic of minorities is not one that is publicly debated in Poland, in the case of minority languages, the issue is left further into the shadows. It seems that problems in minority language education in the case of Slovak are mostly discussed within the minority community itself and then with the Slovak authorities, rather than with the Polish side (The Office for Slovaks Living Abroad, 2011).

The Polish side should attempt to actively engage the representatives of the Slovak minority in a debate on education in the minority language.

Also, opportunities for learning Slovak in schools should be actively promoted within the target groups. The problematic part of the current situation is that the members of the Slovak minority do not feel the support to learn the minority language from the Polish side; moreover, they fear certain discrimination. Thus, in order to fulfil the aims of the language policy to support the maintenance and development of minority languages, it is necessary for the Polish side to take an active part in promoting the learning and usage of such languages.

In the field of the media, the situation is similar. Despite the existence of funds, there does not seem to be active encouragement from the Polish side towards the minorities to apply for them . Although there is no clear link between language maintenance and minority-language media, the existence of such media could at least strengthen the sense of community among the minority group members.

If the language policy is to be successful, other policies have to match its needs, as these policies cannot work separately on the state level. Polish-language policy mixes with its educational and nationalist policy, which can hinder its efficiency by having aims that do not match the aims of the policy towards the minority languages. All in all, minority-language policy in the case of Slovak cannot be considered as fully successful in education and the media. Although there are opportunities for learning Slovak, they do not seem to be actively supported and promoted by the Polish authorities. In the field of the media, there is a print magazine and an online portal in Slovak, but no radio or television shows, despite the existence of funds to support these. It can be argued that the language policy towards minorities in Poland is more ostensible than an actual policy aiming to reach significant goals.

Notes

Note 1: Quotations originally in Slovak have been translated by the author.

Note 2: Gorals = A group living mainly in the area of southern Poland, northern Slovakia, and in the region of Cieszyn Silesia in the Czech Republic.

Note 3: Specifically, the Austro-Hungarian side, to which the area of what is now Slovakia also belonged.

Note 4: Malopolskie voivodeship = An administrative unit of Poland.

Note 5: Both Slovak and Polish are West Slavic languages and the majority of inhabitants of Poland are Catholic, which is also the case for the Slovak minority living there.

Note 6: The Polish school system consists of preschools, primary schools(which children start usually at six years of age and complete six grades), and lower high schools (equivalent to grades 7-9). Then, pupils can continue to upper secondary education, either to liceum (three years), or to technikum (four years).

References

2nd report for the Secretary General of the Council of Europe concerning implementation of provisions of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages by the Republic of Poland (2015). Republic of Poland.

Alba, R. & Nee V. (2003). Remaking the American Mainstream. Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Andráš, M. (2001). Osudy hornej Oravy a severného Spiša [The Fates of Upper Orava and Northern Spiš]. Slovo.

Application of the Charter in Poland - 2nd monitoring cycle (2015). Council of Europe.

Cormack, M. & Hourigan, N. (eds.) (2007). Minority Language Media: Concepts, Critiques and Case Studies. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Dohoda medzi vládou Slovenskej republiky a vládou Poľskej republiky o kultúrnej, vzdelávacej a vedeckej spolupráci [Agreement between the Government of the Slovak Republic and the Government of the Republic of Poland on cultural, educational and scientific cooperation] (1991). Government of the Slovak Republic.

European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (1992). Council of Europe. European Treaty Series, 148.

História - Život [History - Život magazine] (2010). The Association of Slovaks in Poland.

Baldauf, R. B. & Kaplan, R. B. (Eds.) (1997). Language Planning from Practice to Theory. Clevendon: Multilingual Matters.

Kokaisl, P. & col. (2014). Po stopách Slováků ve východní Evropě. Polsko, Ukrajina, Maďarsko, Rumunsko, Srbsko, Chorvatsko a Černá Hora [Following the steps of Slovaks in the Eastern Europe. Poland, Ukraine, Hungary, Romania, Serbia, Croatia and Montenegro]. Praha: Nostalgie.

Liceum [Lyceum] (2015). Zespół Szkół im. Bohaterów Westerplatte.

Majeriková-Molitoris, M. (2013a). Vojna po vojne: Severný Spiš a horná Orava v rokoch 1945 – 1947 [A war after the war: Northern Spiš and Upper Orava in the years 1945-1947]. Kraków: Spolok Slovákov v Poľsku.

Majeriková-Molitoris, M. (2013b). Kto sú Slováci v Poľsku podľa sčítania z roku 2011? [Who are the Slovaks in Poland according to 2011 census?] Život, 55 (4), pp. 26–27.

McCrone, D. and Kiely, R. (2000). Nationalism and Citizenship. Sociology, 34 (1), pp. 19-34.

Milová, P. & Zittová, N. (2014). Slováci v Polsku [Slovaks in Poland]. Hospodářská a kulturní studia.

Moskal, M. (2004). Language minorities in Poland at the moment of accession to the EU. Revista de Sociolinguística, 1-11.

Poland - Reservations and Declarations for Treaty No.148 - European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (2009). Council of Europe.

Poland - Specific policy issues and recent debates - Language issues and policies (2014). Compendium: Cultural policies and trends in Europe.

Poľská republika [The Republic of Poland] (2012). The Office for Slovaks Living Abroad: Slovaks Abroad.

Poľsko [Poland] (2015). Ministry of Education of the Slovak Republic.

Rykała A. (2014). National, ethnic and religious minorities in contemporary Poland. In Marszał, T. (red.) Society and space in contemporary Poland (pp. 137-170). Łódź University geographical research, Łódź.

Slovenčina na Orave a Spiši v školskom roku 2015/16 [Slovak language in Orava and Spiš in the school year 2015/16] (2016). Život.

Spolsky, B. & Shohamy, E. (2000). Language Practice, Language Ideology, and Language Policy. In: Lambert, R. D. & Shohamy, E. (Eds.) Language Policy and Pedagogy: Essays in honor of A. Ronald Walton (pp. 137-170). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

The Act on the Polish Language (1999). The Parliament of the Republic of Poland.

The Constitution of the Republic of Poland (1997). Dziennik Ustaw No. 78, item 483.

The Regional Language, National and Ethnic Minorities Act (2005). The Parliament of the Republic of Poland.

V Poľsku klesá záujem slovenských detí o výučbu slovenčiny, okrem asimilácie naň vplýva aj nesúlad školských zákonov dvoch susedných krajín a poľská národnostná politika [Interest of Slovak children in learning Slovak decreases in Poland, except for assimilation it is influenced by disharmony of school laws of two neighbouring countries and Polish nationalist politics] (2011). The Office for Slovaks Living Abroad.