When myths collide: Bolsonaro’s reaction to the coronavirus crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused major economic, social, cultural and political changes on a global scale. As many of the world’s countries have implemented safety measures such as quarantines and lockdowns, a significant proportion of the human population is spending large amounts of time at home. As a result, the consumption of media – in all of its forms – has increased considerably (Blommaert, 2020; K. Jones, 2020). Multiple actors have taken advantage of this situation to spread discourses that are connected to their particular interests – including extremist messages, fake news and junk news (Maly, 2020). By adopting the Barthian definition of myth as depoliticizing and dehistoricizing discourse that empties and impoverishes reality (Barthes, 1991), we can qualify many of the discourses that have emerged during this crisis as myths.

Myth, mythification and Bolsonaro's populism

Myths are not consistent. They do not have a life of their own and are always associated with other historical discourses – which they corrupt in insidious ways, forming poor and incomplete images of things (Barthes, 1991). Despite its elusiveness, mythical discourse is supported by material objects such as visual and written discourses (Barthes, 1991). The rise of social media in the last two decades has favored the quick and widespread dissemination of myths – some of them stronger than others.

Brazil’s president Jair Bolsonaro is known by his supporters as “O Mito” (“The Myth”) – as if he was a legendary figure, a hero who has come to bring significant positive changes to the country. Conversely, the moniker is ridiculed by those who oppose him. This is because the ultraconservative politician’s discourse is filled with oversimplifications and exaggerations (i.e., myths in the Barthian sense), and his political career has been considerably aided by fake news spread by him and his supporters on social media. In this sense, Bolsonaro is no different from other prominent populist leaders such as Donald Trump and Narendra Modi.

Bolsonaro’s response to the COVID-19 crisis has astonished large segments of the Brazilian population and resonated abroad. The president of Brazil has systematically downplayed the risks associated with the pandemic, refusing to implement nationwide safety measures and going as far as attending political rallies and encouraging people to protest against the lockdowns enforced by the country’s individual states and cities. Bolsonaro’s attitudes and discourses have led him to be denounced to the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity (Brandão, 2020). Moreover, his behavior – both online and offline – has contributed to the dissemination and consolidation of a series of myths related to himself and the coronavirus crisis (some of which will be discussed in the next section).

When propagating mythical discourses, populist politicians help shape public debate and perception on diverse issues – including the way they themselves are viewed by audiences. This way, prominent populists not only reinforce other myths, but also help construct their own mythical images. These discursive practices are embedded in a complex and polycentric phenomenon which I call mythification. Mythification is the process by which an overarching myth is collectively constructed by the merging of multiple myths, ideologies and discourses – something which is effectuated (in)voluntarily by many actors, in different online/offline environments and through diverse mediatic channels. The resulting myths might refer to abstract concepts (e.g. technology, neoliberalism), prominent personalities (including political leaders, elite athletes and artists) and non-sentient entities (such as the COVID-19 virus). Despite this broadness, the most important feature that all myths have in common is the fact that they are instruments of power that are used to legitimize – and normalize – other systems of belief. Myths are always attached to larger ideologies (Barthes, 1991), with which they are entangled in a symbiotic feedback loop – both mutually influencing and feeding off each other. It must be stressed that the processes described above are by no means harmonious, predictable or controllable – mythification often involves discursive clashes and unexpected changes in meaning and uptake.

The COVID-19 virus has influenced collective imagination to a level that few diseases have achieved.

When it comes to contemporary populism – which, due to its strong interconnections with digital environments is also known as algorithmic populism – the mythification process involves a large number of human and non-human participants including politicians themselves, their supporters and detractors, activists, mainstream media outlets, social networks, electronic devices and algorithms (Carrington, 2015; Maly, 2019).

As mentioned above, the construction of myths is greatly aided by social media. These networks’ collective, fragmented and multimodal nature – as well as their ubiquitous presence – increases the speed of communication and favors the production and diffusion of content which is often characterized by original uses of intertextuality and interdiscursivity (Vásquez, 2015). Eye-catching memes, collages, remixes and parodies help convey political ideas – and attacks – in a way that is engaging and attractive to contemporary audiences. Nonetheless, mythification does not necessarily involve creativity. The simple fact that most social media and mainstream news websites have features such as comment sections and social buttons enables users to take part in debates, endorsing or challenging mythical discourses.

Mythification is also connected to globalization. Powered by the hyperconnectivity of our times, contemporary mythical discourses travel at a speed that was unthinkable a few years ago, often reaching multiple corners of the world simultaneously. Because myths have no fixity and are shape-shifting concepts (Barthes, 1991), during this process they can be adopted by different populations and adapted to specific contexts – gaining local features and new meanings.

Moreover, globalized mythical discourses can be reinforced by local myths – and even merged with them, giving birth to new discourses that are considerably different from the original myth. Nevertheless, globalized myths sometimes have to compete against local myths – and they are not always successful in supplanting more established local discourses. Alternatively, even when there is no competition, global myths might simply be rejected or not understood by certain populations. In this sense, the power (or lack thereof) of myths to be propagated is related to the concept of voice – the “capacity for semiotic mobility”, as defined by Blommaert (2005, p. 69).

The COVID-19 crisis has given rise to a remarkable amount of myths that simultaneously complement, challenge, reinforce, undermine and merge themselves with the mythical discourses pertaining to another global phenomenon – the emergence of new right-wing populism. In the next section, I will discuss some of these interconnections, focusing on the Brazilian context and on certain aspects of Jair Bolsonaro’s discourses on social media.

Challenging mainstream views

Due to its global reach and potential lethality that has led to safety measures being implemented by many countries and intense media coverage, the COVID-19 virus has influenced collective imagination to a level that few diseases have achieved. The COVID-19 myth encompasses many discourses, including: the personification of the virus as an “invisible enemy” (almost as if it was a conscious, sentient entity); the belief that the current pandemic has supernatural – or divine – origins; racist discourses that blame people of certain ethnicities for the emergence and spread of the disease; an abundance of references – on internet memes and other media – to science fiction and dystopian scenarios; and conspiracy theories which suggest that the virus has been created by national governments or multinational companies.

In this strongly mythified scenario, Bolsonaro has chosen to challenge the dominant narrative. In March, the Brazilian president repeatedly downplayed the COVID-19 pandemic, describing the disease as a “little cold” and blaming mainstream media for fueling “mass hysteria” (Watson, 2020). By attacking mainstream media, the right-wing politician has relied on a common populist myth (the media as an enemy) to justify his stance. Moreover, Bolsonaro has employed other discourses that are related to fascist and nationalist ideologies such as emphasizing his purported virility – by stating that, due to his background as an athlete, he had no reasons to fear the virus (Fishman, 2020) – and also claiming that Brazilians were naturally immune to diseases, when he implied that the country’s nationals could “swim in sewage without catching anything” (T. Phillips, 2020).

The process of mythification also encompasses less direct forms of expression which are made possible by typical social media features such as likes and other reactions.

These statements, however, were overshadowed by the ultraconservative politician’s presence, on March 15th and April 19th, at two far-right rallies. Both protests supported antidemocratic causes including the shutdown of Congress and the Supreme Court, a military takeover of the government and the institutionalization of censorship. Furthermore, the two demonstrations happened at a time when many of Brazil’s governors and mayors had implemented social isolation measures in an attempt to prevent the spread of the virus. Even more significantly, it was rumored that Bolsonaro himself had been infected with the coronavirus – which, if true, would mean that he had put the other demonstrators at risk of contracting the disease.

Despite the controversial character of the president’s actions – which were harshly condemned by the country’s mainstream media – his social media accounts published pictures and videos which showed his participation in both protests. Therefore, Bolsonaro made use of physical/offline activities to reinforce his online discourses and appeal to his social media followers. Nevertheless, the strategy attracted harsh criticism from many social media users.

(Figure 1. Video shared by Bolsonaro on Instagram, showing his participation in the April 19th protest)

On April 19th, Bolsonaro’s Instagram profile posted a short video (fig. 1) in which the president addressed far-right demonstrators by saying: “I am here because I believe in you. You are here because you believe in Brazil”. Many people criticized the politician’s attitude, including a user named @larissariosfranco, who wrote: “[This is the] Only country without unity. The only country in which the president resembles a stubborn child. The only country in which the president goes against the world, against qualified doctors and educated scientists. Regrettable!”.

Larissa’s comment received 899 likes – being one of the most liked comments on that video. This reveals that a considerable number of people who viewed Bolsonaro’s post oppose the president and endorse this commenter's views instead. Nevertheless, many of the users who replied to her comment attacked her arguments and expressed support for Bolsonaro. This imbalance might suggest that many of Bolsonaro’s detractors prefer endorsing other people’s comments to actually engaging in debate and openly expressing their opinions. Therefore, the process of mythification also encompasses less direct forms of expression which are made possible by typical social media features such as likes and other reactions.

@larissariosfranco’s comment argues that the president’s actions are irresponsible and anti-scientific – by going against the recommendations of doctors and scientists – and implies that Brazil is isolated in its approach to the COVID-19 crisis. Therefore, the user endorses globalized discourses in an attempt to delegitimize the far-right politician’s message. Nevertheless, Larissa’s arguments are also based on a myth: the myth of global unity during the crisis, which ignores the considerable differences in each country’s approach to the pandemic as well as the internal divisions many other countries are facing. Consequently, in this case the user challenges the local/nationalistic myths embedded in Bolsonaro’s approach by embracing a global myth related to the COVID-19 crisis. Interestingly, the comment makes no mention to the demonstration that is shown in the video or to its antidemocratic character.

Evidently, Bolsonaro and his supporters have their own arguments to justify their stance during the pandemic. The former army captain has repeatedly stated that the economic consequences of the lockdown are far worse than the damages caused by the virus. This discourse is aligned with the ideas defended by many Brazilian neoliberal economists and businesspersons (Filho, 2020). Nevertheless, it ignores the threat the COVID-19 virus poses to the less privileged segments of the country’s population – in particular, those who have little or no access to proper sanitation and health services (D. Phillips, 2020). Furthermore, although Bolsonaro argues that, if the lockdown goes on, the resulting economic crisis will decrease the standard of living of the lower classes, he does not mention the fact that his administration has made considerable budget cuts to social welfare programs (Filho, 2020; Resende & Brant, 2019).Therefore, the mythical discourse employed here hides part of the broader context while subscribing to neoliberal ideas.

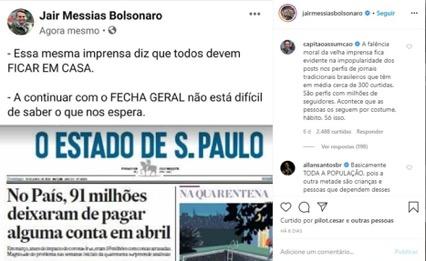

In defending his arguments, the Brazilian president often makes use of content published by mainstream media outlets. On April 20th, Bolsonaro’s Instagram account shared a screenshot of a headline published by the Brazilian newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo (fig.2). The headline reads: “Nationwide, 91 million people have not paid at least one of their bills in April”. Upon sharing the image, the politician commented: “This is the same press which says that everyone must stay home. If the general shutdown goes on, it is not hard to know what awaits us”.

This interaction reveals the ambiguity of Bolsonaro’s relationship with mainstream media. At the same time that the ultra-right-wing politician harshly criticizes established news outlets – employing the myth of “the media as an enemy” and suggesting that they are biased and involved in a conspiracy against him – he bases his arguments on information published by the traditional newspapers he attacks.

Bolsonaro’s attempt to legitimize his views can be characterized as mythical discourse that distorts and contradicts reality.

Interestingly, the most liked comment on this post – published by Captain Assumção, a far-right politician who is one of Bolsonaro’s most active online supporters – argues that traditional Brazilian newspapers are in decline because their social media posts “only have, on average, around 300 likes”. Assumção’s arguments are based on another myth: the claim that mainstream media are being supplanted by new digital media – a discourse that is commonly used by contemporary populist politicians. His views, however, are not based on data such as newspaper sales or their amount of subscribers. Instead, the argument is centered on one of the typical features of social media – the possibility to react to or “like” a post. In this sense, Assumção’s opinion is influenced by the architecture of social networks, which hierarchizes users by their amount of followers or the number of likes they receive. This evidences the way by which the technical affordances of social media contribute to the construction of meaning (Maly, 2019). By blending social media and traditional media in their discourses, the two conservative politicians highlight the complex interconnections between older and newer means of communication that characterize the process of mythification.

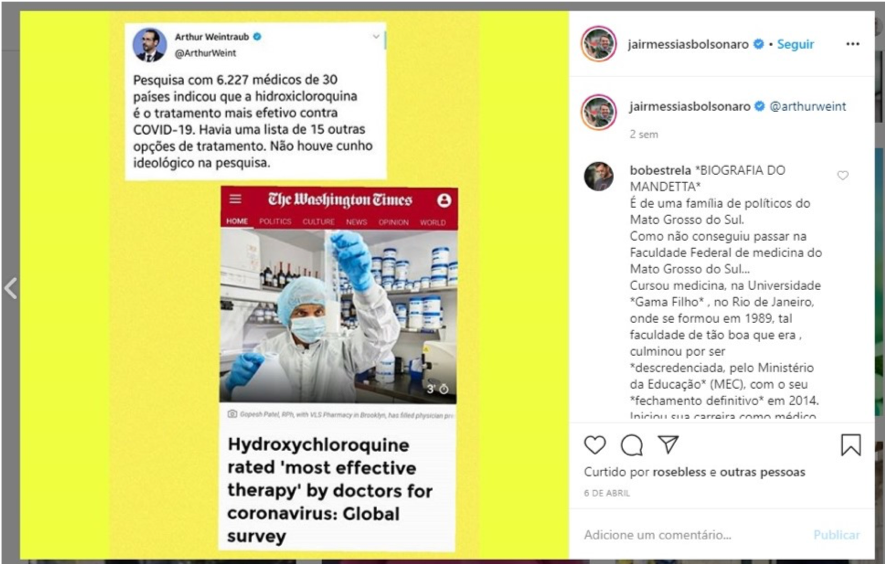

Although Bolsonaro and his supporters have denied the importance of the COVID-19 crisis, they have embraced a purported solution for the pandemic. The president has constantly touted a medicine known as hydroxychloroquine as the supposed cure for COVID-19. In doing so, he mirrors the response of another populist leader – Donald Trump, the president of the United States – to the pandemic. Even though both presidents have adopted a similar rhetoric, this does not presuppose the existence of a common populist counternarrative to the dominant views in the scientific community. In fact, populist politicians from various countries have responded to the COVID-19 crisis in different ways – some have implemented or advocated for strict safety measures (Mudde, 2020).

Notwithstanding Trump and Bolsonaro’s defense of the drug, the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine against COVID-19 is yet to be proven (“Myth: Anti-malarial drugs”, 2020). Therefore, by adopting an anti-scientific stance, Bolsonaro is endorsing a myth that has achieved considerable reach. In doing so, he also makes use of traditional media sources in an attempt to prove his point (fig. 3).

(Figure 3. The Brazilian president has touted hydroxychloroquine as the solution for the pandemic)

On April 6th, the president’s Instagram account posted a screenshot of a headline published by English-language newspaper The Washington Times. The image was accompanied by the screenshot of a tweet by Arthur Weintraub – one of Bolsonaro’s special advisors – in which Weintraub highlights the purported effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine, stating that the research concerning the medication is “non-ideological”. Besides the fact that Weintraub is a lawyer – and not a health authority or a medical researcher – The Washington Times is an American right-wing newspaper which has been criticized multiple times for publishing biased and questionable news articles (Beirich & Moser, 2003; “Washington Times”, n.d.). Consequently, Bolsonaro’s attempt to legitimize his views can be characterized as mythical discourse that distorts and contradicts reality (Barthes, 1991).

A multifaceted phenomenon

In analyzing certain aspects of Bolsonaro’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, I have attempted to shed light on some of the processes that make up the phenomenon known as mythification. By alluding to mainstream media sources and sharing their content on his social media accounts, the ultra-right-wing politician exemplifies how contemporary populist discourses are shaped by the multiple channels that are part of the hybrid media system (Chadwick, 2013). The mythical image of populists – as well as the myths associated with the COVID-19 pandemic – are constructed by many different actors such as politicians themselves, their supporters and detractors, traditional media outlets and social networks (including their technical affordances). Moreover, Bolsonaro’s offline actions – such as his participation in far-right rallies – and his online activity complement and influence each other, highlighting the integration between offline and online environments that is characteristic of the post-digital age (Albrecht, Fielitz & Thurston, 2019; R.H. Jones, Chik & Hafner, 2015).

As stated above, myths are always tied to overarching ideologies. This way, Bolsonaro’s response to the COVID-19 crisis comprises a series of mythical discourses that endorse – among other ideas – neoliberal, nationalist and authoritarian beliefs. Although the Brazilian president’s discourse often features globalized myths such as those commonly associated with populism (e.g., “the media as an enemy”), his rhetoric also alludes to ideas and beliefs that have roots in Brazil. Therefore, Bolsonaro’s discourse blends local and global in a particular way, creating new myths and meanings in this process.

The presence of globalized discourses and myths in the arguments employed by Bolsonaro and other social media users highlights the complexity of the current discursive environment. In a hyperconnected world – in which the word "virality" is no longer exclusively applied to diseases, but also to all sorts of myths – researchers cannot prescind from the context of globalization when studying contemporary discourses (Blommaert, 2005). The broadness and many intricacies of mythification make it a difficult object of study that can never be fully exhausted. Nevertheless, by shedding light on some facets of the processes of myth construction, researchers can provide important contributions that increase our understanding of various cultural, social and political events – such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

Albrecht, S., Fielitz, M., & Thurston, N. (2019). Introduction. In M. Fielitz & N. Thurston (Eds.), Post-digital cultures of the far right: Online actions and offline consequences in Europe and the US (pp. 7-22). Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Barthes, R. (1991). Mythologies (A. Lavers, Trans.). New York: The Noonday Press.

Beirich, H., & Moser, B. (2003, August 15). The Washington Times has history of hyped stories, shoddy reporting and failing to correct errors. Retrieved from https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2015/washing...

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse: A Critical Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blommaert, J. (2020, March 30). The Coronavirus and online culture: Lessons we're learning. Diggit Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.diggitmagazine.com/column/coronavirus-and-online-culture-les...

Brandão, A. (2020, April 3). Coronavírus: Bolsonaro é denunciado no TPI por “crime contra a humanidade”[Coronavirus: Bolsonaro is denounced at the ICC for “crime against humanity”]. Retrieved from https://www.msn.com/pt-br/noticias/politica/coronav%C3%ADrus-bolsonaro-%...

Carrington, V. (2015). ‘It’s changed my life’: iPhone as technological artefact. In R.H. Jones, A. Chik & C. A. Hafner (Eds.), Discourse and digital practices: Doing discourse analysis in the digital age (pp. 158-174). New York: Routledge.

Chadwick, A. (2013). The hybrid media system: Politics and power. New York: Oxford University Press.

Filho, J. (2020, March 29). Coronavírus: Existe uma lógica genocida por trás do falso dilema entre a economia e vidas [Coronavirus: There is a genocidal logic behind the false dilemma between the economy and lives]. Retrieved from https://theintercept.com/2020/03/29/coronavirus-economia-vidas-logica-ge...

Fishman, A. (2020, April 16). Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, the world’s most powerful Coronavirus denier, just fired the health minister who disagreed with him. Retrieved from https://theintercept.com/2020/04/16/bolsonaro-fires-health-minister-braz...

Jones, K. (2020, April 9). This is how COVID-19 has changed media habits in each generation. Retrieved fromhttps://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/covid19-media-consumption-generat...

Jones, R.H., Chik, A., & Hafner, C.A. (2015). Introduction: Discourse analysis and digital practices. In R.H. Jones, A. Chik & C. A. Hafner (Eds.), Discourse and digital practices: Doing discourse analysis in the digital age (pp. 1-17). New York: Routledge.

Maly, I. (2019, November 26). Algorithmic populism and algorithmic activism. Diggit Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.diggitmagazine.com/articles/algorithmic-populism-activism

Maly, I. (2020, March 23). The coronavirus, the attention economy and far-right junk news. Diggit Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.diggitmagazine.com/column/coronavirus-attention-economy

Mudde, C. (2020, March 27). Will the coronavirus ‘kill populism’? Don’t count on it. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/27/coronavirus-populi...

Myth: Anti-malarial drugs can cure coronavirus. (2020, March 26). Retrieved from https://www.covid-19facts.com/?p=83912

Phillips, D. (2020, April 14). 'We're abandoned to our own fate': Coronavirus menaces Brazil's favelas. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/apr/14/were-abandone...

Phillips, T. (2020, March 27). Jair Bolsonaro claims Brazilians 'never catch anything' as Covid-19 cases rise. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/mar/27/jair-bolsonar...

Resende, T., & Brant, D. (2019, December 26). Bolsonaro cuts government spending in social, culture and labor areas. Retrieved from https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/internacional/en/brazil/2019/12/bolsonaro-...

Vásquez, C. (2015). Intertextuality and interdiscursivity in online consumer reviews. In R.H. Jones, A. Chik & C. A. Hafner (Eds.), Discourse and digital practices: Doing discourse analysis in the digital age (pp. 66-80). New York: Routledge.

Washington Times. (n.d.). In Media Bias/Fact Check. Retrieved April 25, 2020, from https://mediabiasfactcheck.com/washington-times/

Watson, K. (2020, March 29). Coronavirus: Brazil's Bolsonaro in denial and out on a limb. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-52080830