The power of Bolsonaro’s message in his campaign

Brazil’s polarization between citizens who were pro-Bolsonaro of PSL (the Social Liberal Party) and those who were pro-Haddad of PT (the Workers' Party) marked the 2018 presidential election. The way Bolsonaro’s message was constructed and communicated through a hybrid media system is key to understanding how it triggered a huge mobilization power from his supporters, which, together with algorithmic activism and digital bubbles, contributed to his winning.

Brazil before Bolsonaro

In order to understand the outcome of the 2018 Brazilian presidential election, we should go back to 2002, the year in which Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva – or simply Lula – of the leftist Workers’ Party (PT) was elected president of Brazil. PT consecutively won all the following elections until the 2018 one. All those years resulted in growing dissatisfaction among many Brazilian citizens of all classes, who saw themselves in the midst of a huge economic crisis, a period of high inflation and interest rates, and the most resilient unemployment rates in the country so far. During that period in which PT was in power, two big corruption scandals also emerged, and Brazilians didn’t buy the PT members' “I don’t know anything about it” stance. Additionally, fear and insecurity were part of the daily routine in Brazil, a country with around 60 thousand homicides per year.

Bolsonaro YouTube video: "Brazil needs a change of direction”

So, amidst the crisis and emergent anti-PT feelings, combined with a rejection of traditional politics and their “dirty money” as well as the Brazilian people's desire for change, an outsider emerged. Ever unpredictable, Jair Bolsonaro presented himself as an anti-system candidate (“6 motivos porque”, 2018).

Bolsonaro’s pathway to shaping his message

Bolsonaro’s political persona was constructed around what he truly believed and tirelessly defended – his issues. After all, what he is is also what he stands for. Since the very beginning – years before the election – his "fight" stance was against PT and everything that (in his opinion) the party meant and supported: corruption, harmful ideologies such as communism and socialism, and a threat to the so-called “traditional Brazilian family” and its Christian values.

Comment on Bolsonaro's Facebook page: "God bless Mr. President, never give up on Brazil and Brazilian people".

The hybrid media system, built upon interactions among older and newer media logics (Chadwick et al., 2016), was the vehicle through which Bolsonaro communicated his issues. But his campaign was mainly focused on the use of newer media logics rather than older ones. His pathway to communicating his issues to Brazilian citizens passed through YouTube videos, tweets, Facebook and Instagram posts, and last but not least, WhatsApp.

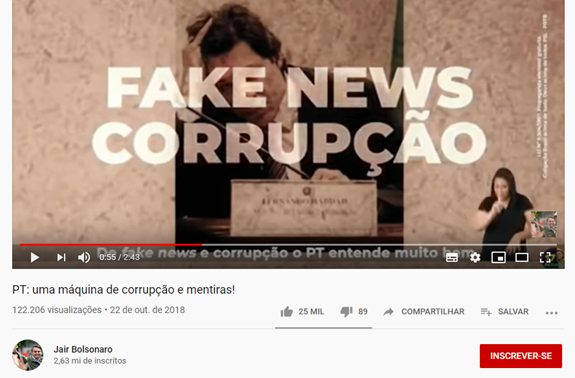

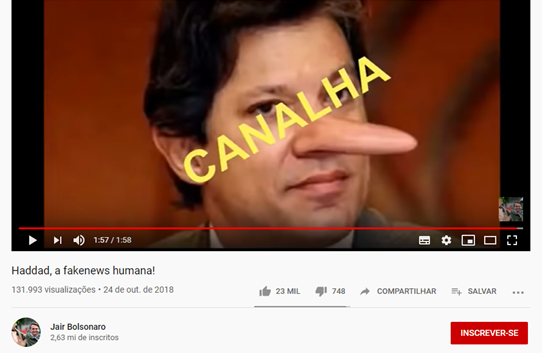

Bolsonaro constantly accused PT and his opponent, Fernando Haddad, of being corrupt. By that time, Haddad was responding to more than 30 such accusations. Bolsonaro, on the other hand, at least up to the point before the election, had no corruption record – which is not so common among Brazilian politicians. His appearance of having a clean record was further boosted by the contrast with the multiple corruption scandals his opponent was involved in.

Video posted by Bolsonaro on his YouTube channel (10/22/2018): "PT: a machine of corruption and lies".

Aside from the fight against corruption, Bolsonaro also made polemic declarations about the “traditional Brazilian family”, stating that “Haddad is the Brazilian family’s enemy”, “Brazil is a Christian country and Haddad mocks our faith”, and “we need to value our Brazilian family. Haddad doesn’t know any biblical passage”. This rhetoric was also related to his fight against gender ideology (“Chegamos na reta final”, 2018).

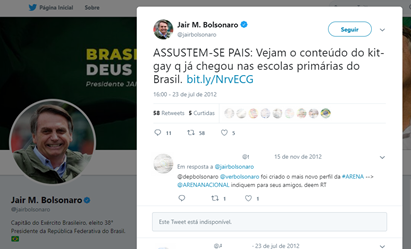

Bolsonaro tweets about the so-called "gay kit" (07/23/2012): "PARENTS, GET SCARED: Look at the content of the gay kit, that has already arrived in Brazil’s primary schools".

On the issue of gender and sexuality, Bolsonaro criticized Haddad’s alleged attempt to implement the so-called “gay kit” in Brazilian schools. He was actually referring to a project called “School Without Homophobia”, which aimed to promote citizenship and human rights for the LGBT community. Bolsonaro thus claimed that Haddad was responsible for presenting this "gay kit" when he was São Paulo’s mayor.

Haddad in his Twitter refuting Bolsonaro: "For the umpteenth time, Bolsonaro is refuted" It is #FAKENEWS that Haddad created a "gay kit" and that the lower house realized a LGBT seminar for kids".

In truth, Haddad had done nothing of the sort – it was fake news (“Haddad não criou”, 2018). Still, Bolsonaro stated in his videos that “Haddad wanted to implement the “gay kit” in schools so that the poor children have sex lessons by the age of 6. This is insane” and that “they [PT politicians] want to legalize pedophilia; they want to sexualize our children; they implemented the “gay kit” under the name “School without Homophobia”” (“Sexo para crianças”, 2018; “Chegamos na reta final”, 2018).

Bolsonaro on his YouTube channel (10/22/2018): "It is our duty to preserve our children's innocence".

The fake news spread went further than the supposed “gay kit” implementation. Bolsonaro often recorded videos to specifically clarify some accusations that were circulating around about him. Some of them were that he was an anti-Christian, that he wanted to kill gays and indigenous people, to distribute weapons to everyone, to deforest the Amazon rainforest, and so on (“Novas informações”, 2018).

Bolsonaro on his YouTube channel (10/24/2018): "Haddad, the fakenews man!".

So, Bolsonaro assumed the position of telling the so-called truth to the Brazilian nation – “we made a campaign based in truth, and the other side made it based on lies”, he stated (“Novas informações”, 2018). On his website's front page, above his slogan (“Brazil above everything, God above everyone”), one finds a link for “The Truth”, which appears even before his biography – is his duty of telling the truth to Brazilian citizens more important than who he is?

Bolsonaro's webpage slogan: "Brazil above everything, God above everyone".

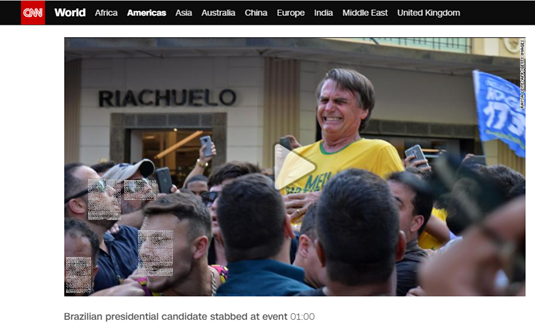

Besides the fake news spread, which assumed a huge role in Bolsonaro’s campaign, one of the most defining episodes of his election process came when he was stabbed during a rally in Juiz de Fora, on September 6th (approximately 1 month before the first round of the election). He lost 40% of his body’s blood and underwent several surgeries (“Bolsonaro presidente”, 2018).

As a result, his opponents softened their attacks against him – after all, he was seriously injured and it was not acceptable to attack someone hospitalized. Bolsonaro constantly updated his supporters with news about his recovery – showing that, even in that condition, he would continue fighting for Brazil. The visibility he gained over time favoured his campaign as he often shared his daily routine after the attack with his followers. This gave his fans the feeling of being close to him: Bolsonaro was more than their potential future president. He was their friend.

Bolsonaro's Instagram post

In the end, the stabbing episode gave Bolsonaro not only more television air time, but also an opportunity to appear on television with the image of a stabbing victim – or even a hero (“Eleição de Bolsonaro”, 2018).

Identification with Bolsonaro’s embodied message

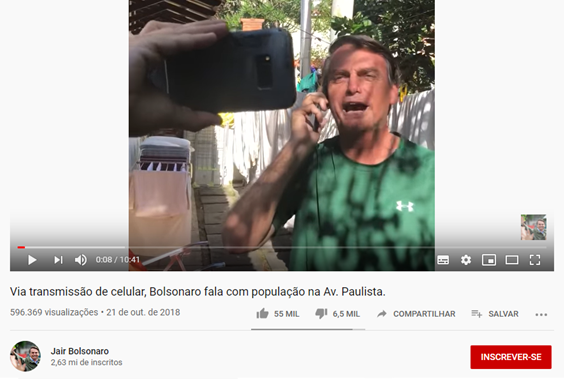

What Bolsonaro fought for combined with how he managed to transmit it was key for his campaign – because his message was not only about his issues, but also about how he communicated them. Bolsonaro’s style – the way (his) image is communicated (Silverstein, 2003) – was seen in his informal and non-filtered language; in his emotional anti-PT and anti-left discourse; in his casual and “common Brazilian man” clothes; in his strong and angry gestures. He often screamed, got angry and said whatever came to his mind – a concern about formalities was not really present in many of his appearances. He successfully inhabited (his) “message” in the act of communicating (Silverstein, 2003).

Bolsonaro on his YouTube channel "Transmission via cellular phone: Bolsonaro talks with the people in Paulista Avenue".

In other words, Bolsonaro constructed his identity embodying his message and being “on message” – a term referring to the consistent, cumulative, and consequential image that a public person has among his or her addressed audience (Silverstein, 2003). In fact, his addressed audience identified not only with his issues, but also with the “Bolsonaro way” of communicating them.

Facebook post from a fan: "Would you have breakfast with this humble sir?"

People started noticing that Bolsonaro looked more like a common Brazilian man than a politician. This attracted audiences – was Bolsonaro one of them? He spoke not only to them, through direct interaction on social media, but also for them. His audience’s issues were also his issues – he was their voice. So, through their identification with his message, his supporters started to actively participate in its continuing construction.

Bolsonaro supporters' algorithmic activism

In order to understand power, one needs to examine the relations between social actors and between social actors and media technologies. Within a context of power relations, even the most powerful must cooperate with the less powerful. Campaigns use hybrid strategies in order to mobilize citizens, but on the other side, citizens can also use and inhabit digital media to influence and spread campaign messages (Chadwick et al., 2016).

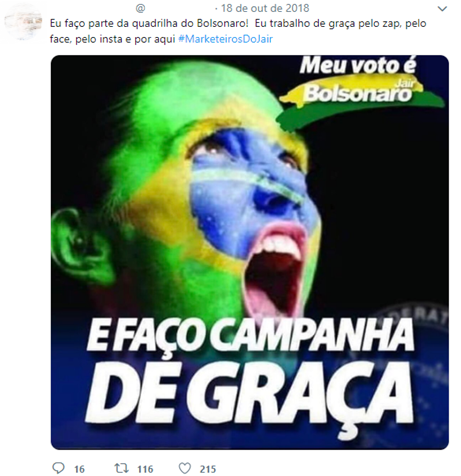

In big organizing, in which millions of people are mobilized in order to achieve a shared goal, volunteers act as campaign staff (Bond & Exley, 2016). In fact, the role of Bolsonaro’s supporters as volunteers was not small at all.

It is estimated that the cost of the US presidential race in 2016 was about $30 per potential elector. France, a country considered to have low electoral campaign costs, spent around $1.9 per potential elector in 2012 (“Quanto custam as”, 2016). In his campaign, Bolsonaro spent approximately $0.01 per vote (“Bolsonaro gastou”, 2018). He owes this extremely low $0.01 figure to his “army” of volunteer supporters, who engaged in spreading his message mainly (although not exclusively) through digital platforms.

Tweet from a fan: "I belong to Bolsonaro's gang! I work for free through Whatsapp, Facebook, Instagram and on #MarketersOfJair. Text on the Image: "My vote is Jair Bolsonaro and I campaign for free".

Technology – and thus all kinds of digital platforms – certainly also contributed to this $0.01 figure. It allowed the volunteer leaders to reach as many people as possible and enabled potential voters to get acquainted with the campaign plan (Bond & Exley, 2016). In order for such outreach to be efficient, the simple use of a digital platform is not enough. The actors need to know how to use the platform – they need to know why, how, when, and for whom to re-tweet, like, share or forward a message.

Algorithmic activism consists in spreading a politician’s message through interactions with one of their posts, in order to trigger the algorithms of the digital platform and boost the post’s popularity, and thereby also the politician’s popularity. So, this type of activism also presupposes that the activists know how to use digital platforms (Maly, 2018). In Bolsonaro’s campaign, this was crucial.

Pro-Bolsonaro memes: "When you are an outlaw and realize that Bolsonaro was elected"

The organization and distribution of messages could be achieved through WhatsApp, the political "education" through YouTube, the political battle through Twitter, and the network boost through Facebook (“É hora de se”, 2018). The actors within a hybrid media system need to judge which combination of media is more adequate to shape a political process (Chadwick et al., 2016). Even memes were used as propaganda for Bolsonaro.

In the end, Bolsonaro supporters' algorithmic activism was dependent on the different platforms used by the actors and their competences in using them since, for example, Twitter logic is different than WhatsApp logic. In addition, the activists' level of knowledge, their mobilization power, and financial means typically also play a role in these cases (Maly, 2018). Of course, the financial means were not so relevant to Bolsonaro’s campaign, as illustrated by the $0.01 figure. Therefore, the answer for his victory might lie in other (digital) aspects.

WhatsApp: the ace up Bolsonaro's sleeve

WhatsApp was the ace up Bolsonaro’s sleeve in his campaign. His support network built on WhatsApp assumed the role of being one of the main communication tools of his electorate. BBC Brazil reported that Bolsonaro himself was a member of many WhatsApp groups, and sometimes he was the one who went after internet militants. This kind of interaction, which originates in digital media logics, allowed his supporters to easily reach him in the absence of traditional and institutionalized mediators.

In one video posted on a Facebook page called “Jair Bolsonaro Presidente 2018”, Bolsonaro appears holding a smartphone and saying “I will answer everyone (on Whatsapp) in a while, ok? I’m just going to drink a coffee first” (“Como exército”, 2017). Bolsonaro's friendly approach slowly deconstructed the image of unapproachable politician and built one of a politician that is a friend who listens and talks to the people – someone reachable and closer to their reality.

Pro-Bolsonaro Whatsapp groups

An article from Folha de S. Paulo, one of Brazil’s leading newspapers, accused some Brazilian entrepreneurs of illegally bankrolling a campaign to bombard WhatsApp users with fake news about PT and Haddad (“Bolsonaro business”, 2018). Bolsonaro responded by criticizing the newspaper and accusing them of being responsible for circulating fake news (“Bolsonaro presidente”, 2018). In reality, because of its decentralized structure and easy dissemination, it was WhatsApp that facilitated the circulation of fake news, which could have favoured the far-right winner (“WhatsApp fake news’”, 2019).

Digital bubbles and online polarization

Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and any other digital platform may be understood as channels of information filled with emotional conduits, through which actors can express their anger and desire for change, mobilizing other actors that feel the same. Therefore, social media shape the way people come and act together – they choreograph collective action (Gerbaudo, 2014). The mobilization of collective action in Bolsonaro’s campaign remained within social media’s boundaries, in which any actor contributed to spreading the candidate’s message with a click, a like or a share.

Concerns about the use of social media in such cases relates to when their use is not accompanied by interaction with those on the other side of a debate (Gerbaudo, 2014). Human beings have a tendency to connect and bond with others that are similar to them – they show “homophily” (Sunstein, 2018). The army of Bolsonaro’s volunteers started with a small group of people sharing the same feelings and interests as him.

On the left, Bolsonaro supporters. On the right, PT supporters.

The digital world, through algorithms, reinforces homophily by creating digital bubbles. People are not exposed to other perspectives, interests and convictions, so they end up living in different political universes (Sunstein, 2018). The newsfeeds of Bolsonaro’s supporters were not nearly the same as those of Haddad’s voters. The problem is that, sometimes, people are not conscious of this difference – algorithms create these bubbles for them based on their interactions on digital platforms.

On the other hand, some bubbles are created very consciously. This was the case for some pro-Bolsonaro groups, which operated apart from the mainstream public sphere by banning “undercover” leftists and “communist” content – possible threats that could show to Bolsonaro’s potential voters other perspectives, and thereby convert them to Haddad’s side (“On Digital Populism”, 2019).

How did he do it?

Months after the presidential elections that led to his win, many Brazilians – and the world – remained with the question: how did Bolsonarodo it? The way Bolsonaro constructed and communicated his message awakened a common feeling between many dissatisfied Brazilians that started yearning for a change in Brazilian politics. In fact, they ended up getting a huge change, but Bolsonaro did not bring this change about alone.

The mobilization power of a small group of Brazilian citizens, who years later became the nearly 58 million people who voted for him in the second round of elections, was what made this change possible. Bolsonaro built his followers, and then his followers voluntarily put themselves in charge of spreading his message. They knew how to use new media effectively to make that happen. They knew its logics.

Bolsonaro on Globo News with text "God, Family, Brazil" written on his hand

Rather than questioning why Bolsonaro was elected, one should question how. The “why” can be explained through the analysis of the Brazilian context before Bolsonaro. But the “how” goes more deeply. The logic of Bolsonaro's presidential campaign changed traditional political marketing and it shows the importance of a coherent construction and maintenance of a politician’s message, image and style. And, of course, it shows that the politician is not alone – Bolsonaro’s victory says more about the Brazilian people than it does about Bolsonaro himself.

References

Chadwick, A., Dennis, J., & Smith, A. P. (2016). Politics in the age of hybrid media: Power, systems, and media logics. In A. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbø, A. O. Larsson, & C. Christensen (Eds.) The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics. Routledge.

Avelar, D. (2019, October 30). Whatsapp fake news during Brazil election ‘favoured Bolsonaro’

Bond, B. & Exley, Z. (2016). Rules for revolutionairies: How big organizing can change everything. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Bermúdez, A. (2016, November 7). Quanto custam as eleições nos EUA e como elas se comparam com outros países [how much are EUA elections e how they compare with other countries].

Bolsonaro, F. [Flavio Bolsonaro]. (2018, October 26). Chegamos na reta final. Vamos dar o último gás combatendo, COM A VERDADE, as mentiras do PT! [Video File]

Bolsonaro, J. M. [Jair Bolsonaro]. (2018, October 24). Novas informações e mentiras que estão sendo difundidas a meu respeito! [Video File]

Bolsonaro, J. M. [Jair Bolsonaro]. (2018, August 30). Sexo para crianças nas escolas: Jornal O Globo mente mais uma vez! Segue a verdade. [Video File]

Cesarino, L. (2019, April 15) On Digital Populism in Brazil.

Cruz, F. B. & Valente, M. G. (2018, October 22) É hora de se debruçar sobre a propaganda em rede de Bolsonaro [It’s time to elaborate on Bolsonaro’s propaganda network].

Fagundez, I. (2017, May 26) Como exército de voluntários se organiza nas redes para bombar campanha de Bolsonaro a 2018 [how army of volunteers organize themselves on networks to boost Bolsonaro’s 2018 campaign].

Figueiredo, P. (2018, October 12) Haddad não criou o “kit gay” [Haddad didn’t create ‘gay kit’].

Gerbaudo, P. (2014). Tweets and the Streets. Social media and contemporary activism. The introduction.

Gullino, D. (2018, October 30). Bolsonaro gastou 4 centavos por voto; Haddad, R$0,70 [Bolsonaro spent 4 cents per vote. Haddad, R$0.70].

Iraheta, D. (2018, October 29). 6 motivos porque Jair Bolsonaro foi eleito presidente do Brasil [6 reasons whyJair Bolsonaro was elected president of Brazil].

Maly, I. (2018) Populism as a mediatized communicative relation: The birth of algorithmic populism. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, 213.

Phillips, T. (2018, October 18). Bolsonaro business backers accused of illegal Whatsapp fake news campaign.

Ribeiro, I. (2018, October 28) Eleição de Bolsonaro marca mudança no marketing político [Bolsonaro’s election set changes in political marketing].

Silverstein, M. (2003). Talking politics: The substance of Style From Abe to ‘W’. Prickly Paradigm Press.

Sunstein, C. R. (2018). # Republic: Divided democracy in the age of social media. Princeton University Press.