Brexit : An Online Battle With Offline Casualties

This article will analyse the distinct approach that the Leave campaign used on both Facebook and Twitter in the lead up to the Brexit referendum. The nature of Twitter as an online medium served Leave as a platform for mobilising and organising pre-existing supporters. Once coupled with the force of Facebook, which sought to target and convert new supporters, this dual approach enabled Leave to strategically communicate with the entire online potential electorate of British society (Usherwood, 2017) and ultimately reward them with a referendum victory.

Brexit, Twitter and the Leave campaign

In 2009, ex-British Prime Minister, David Cameron praised the internet as a means of “turning lonely fights into mass campaigns, transforming moans into movements, exciting the attention of hundreds, thousands, millions of people and stirring them into action.”

Ironically however, it was the online battlefield that lost him Brexit referendum, ousted him from Downing Street and sent British politics into turmoil as a “monumental act of self harm which will bewilder historians in years to come” (Ashdown, 2017). Ultimately, the Leave campaign’s victory demonstrates the necessity of social media activism in achieving political success in the 21st century.

As a growing and changing phenomenon in the political landscape, social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter enable the direct communication of key messages to the broadest possible audience, without the filter of the mass media. ‘Leave’ recognised the merits of this and invested a significant proportion of its time resources into an extensive and effective social media campaign (Silverstein, 2003).

Figure 1: Tweet from official Vote Leave account

To determine how Leave successfully utilised Twitter, it is necessary to consider how this platform works and therefore how it can be used to guarantee political advantage.

Twitter grants autonomy to users in deciding what accounts to follow and thus what information they are exposed to. In customizing their online environment, users are more likely to subscribe to information that adheres to their worldview through the endorsement of similar content to what they believe in.

This creates ‘echo chambers’ in which users will experience continued interaction with sources that reinforce the polarization of messages, political or otherwise. The prevalance of such was found in in a study of 15,299 Twitter users on the subject of the Brexit referendum during the official ten-week campaign period. Conducted by the University of London and published in the journal PLOS ONE, 69% of pro-leave messages were interactions with other pro-leave accounts. This inherent quality of Twitter was harnessed by Leave as demonstrated through choreography of assembly.

Twitter and the choreography of Assembly

With the focus of Leave’s twitter campaign directed at pre-existing voters, such echo-chambers furthered Leave’s ability to mobilise its followers where they were already following and promoting pro-Leave sentiments. Twitter successfully forged the ‘online-offline nexus’ of the Leave campaign and enabled successful choreography of assembly (Maly, 2018).

In the lead up to and on referendum day, the campaign encouraged persons to assist Leave in whatever way they could in a physical ‘offline’ sense, by re-tweeting the actions of similar persons on the official account @vote_leave to encourage similar behaviour from supporters.

This was also critical in guaranteeing the votes of pre-existing supporters. Because the referendum was not compulsory, Leave understood the importance of affirming the views of persons who already favoured leaving the European Union, to ensure that they acted on these opinions by voting.

Figure 2: Collection of Tweets retweeted by @vote_leave

Communicating Brexit as project of hope for the future

The intuitive and overwhelmingly optimistic message purported by Leave on Twitter was also vital to its success, contrasting sharply with the negativity and spitefulness projected in other aspects of the Brexit referendum. By appealing to the emotional rather than rational foundations of the debate on Twitter, voters were largely responsive to this positivity and future-orientated approach. While the relentless tide of negative economic forecasts and complicated arguments promulgated by Remain may have been effective in an academic debate, when it came to Twitter, Leave was dominant in its simplistic and future oriented positivity (Polonski, 2016).

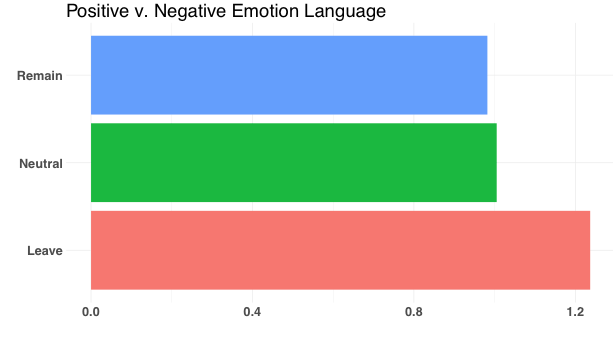

This can be evidenced by comparing the language of Leave users versus Remain users. Research through the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count has found that Leave tweets were generally:

- More associated with the language of reward

- Less sad

- More orientated towards the future, and less towards the past

- Less tentative

- More about assertions of power

- Slightly less quantitative

Figure 3: Analysis of Language of Twitter Users

The general public furthered this overriding theme of positivity and hope purported by the Leave campaign in their tweets. One hashtag created by Vote Leave was #projecthope, which sparked a wave of similarly optimistic tweets that advocated for a ‘brighter,’ more ‘democratic,’ and ‘free’ future:

Figure 4: Collection of Tweets using the hashtag #projecthope, retweeted by @vote_leave

The nature of the 24 hour news cycle, both in traditional media and on the internet means that the public is constantly bombarded with negative news. We are conditioned to accept this as the norm and as such, the sentiment of optimism found in these tweets was arguably effective in driving support for Leave.

Engagement with political and public figures

Another point of interest and benefit was the use of key political and public figures in Leave oriented tweets. The celebration or discreditation of high interest political persons is key in cementing a campaign premise as being in line with the ‘common good’ in a populist campaign. This is a subjective concept in that is both understandable and attainable for the everyday person despite being a ‘moralistic imagination of politics’ (Mueller, 2016).

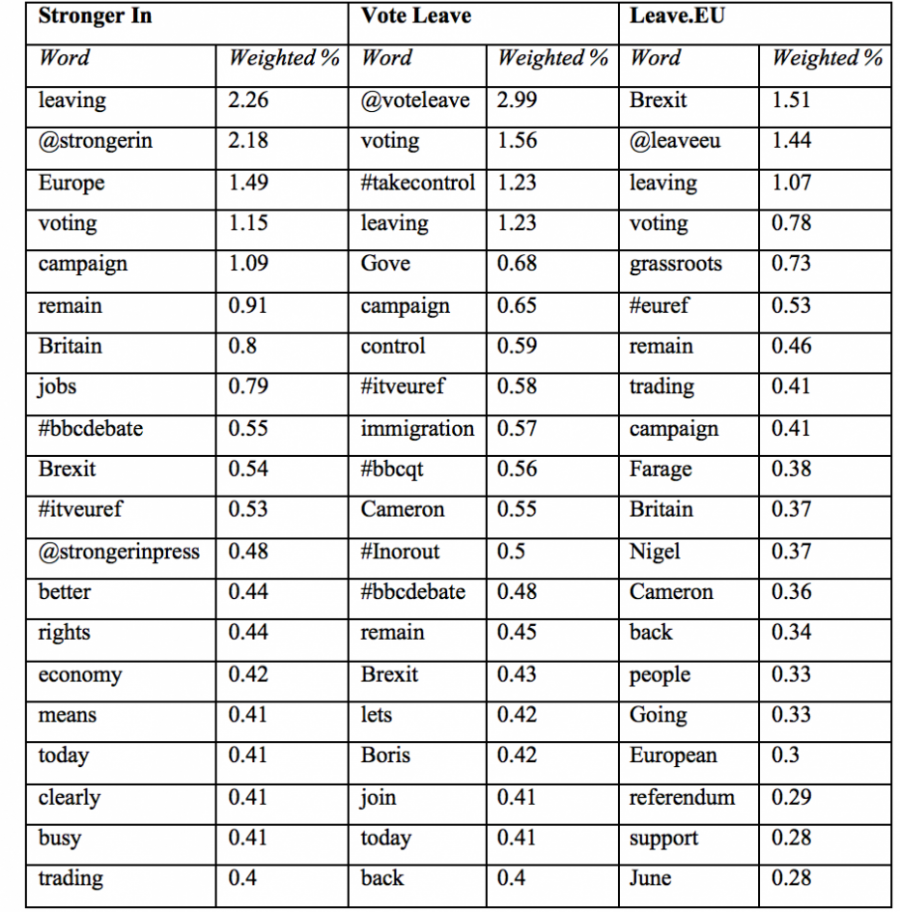

The following data demonstrates the 20 most popular word stems from the three official Twitter accounts centred around the Brexit debate. It shows a distinct lack of individual names used by the ‘Stronger In’ account. By comparison, Vote Leave and Leave.Eu made pointed references to David Cameron, Boris Johnson, Nigel Farage and Michael Gove – all key figures that could be both celebrated and shamed on Twitter.

Figure 5: Comparison of the top 20 word stems by major Brexit twitter accounts

Although anti-elitist by definition, populist campaigns generally seek to portray their own elites as intrinsically connected to the common person by ‘speaking in the name of the people as a whole’ (Mueller, 2016). As demonstrated by this tweet from @vote_leave, Boris Johnson, former mayor of London and conservative member of parliament, is framed as an advocate for common sense by showing his understanding of community needs. It paints him as standing against demanding and privileged European elites that have undermined every aspect of British sovereignty. `

Further, the championing of the values of the common man against the elite undermines an opposing view that becomes illogical and outdated. Tweets against David Cameron, for example, were uniformly negative and used his words and actions against him, while also reminding the anti-conservative votership to vote against him, regardless of the Leave campaign promoting more conservative sentiments. This produces a show of strong and favourable leadership in politicians such as Boris Johnson, which enables a relationship of trust from supporters.

Figure 5: Tweet from official @vote_leave account

The Leave campaign on Facebook

The Leave campaign understood that the Brexit vote would be decided beyond its initial supporter base. As such, it sought to find and appeal to different voter demographics, facilitated by a two pronged approach used on Facebook. This consisted of (1) Data Harvesting and (2) Targeted Campaigning

Data Harvesting in the name of Brexit

Both sides of the debate used sophisticated analytics software that enabled the respective campaigns to apply target advertising. For Leave, much of this operation was achieved by AggregateIQ (AIQ), an obscure technology company based in a small Canadian provincial city. The Leave campaign allocated a mammoth £3.5 million to AIQ, more than 40% of their tax-payer funded budget to this company. Together they attempted to accumulate data for potential voters through complicated analytics software.

Following Leave's Brexit success, AIQ’s website was emblazoned with a quote from Vote Leave’s campaign manager Dominic Cummings that encapsulates the integral role that AIQ played: ‘We couldn’t have done it without them.’ This has since been removed following criticism of AIQ for its apparent improper use of personal data throughout the campaign, likely contributing to Leave's success.

Figure 7: Quote from Dominic Cummings, Vote Leave campaign director

Internally, Leave also performed extensive data mining by drawing information from various online sources such as social media traffic. This allowed for the creation of detailed voter profiles. Likes, comments and shares were all valuable tools in determining voter support.

An example of this was through a data harvesting competition on Facebook which offered fans the chance to with £50 million if they correctly predicted the outcome of every European Championship game that year. Conditions for entering included the submission of an entrant's name, age, gender, address and notably, who they were planning on voting for in the Brexit referendum.

Figure 8: Example of targeted campaigning by Vote Leave

Dominic Cummings affirmed the political nature of this facebook campaign after the referendum was over, saying they sought knowledge relating to young males who typically "ignored politics".

This effectively allowed Leave to gather data on a pool of people who were particularly diffcult to reach politically. This was designed to increase voter turn out in Leave's favour by targeting a new demographic from the information obtained. Such campaigns were simply not reflected by the Remain side, posititioning Leave to harness greater voting power.

Targeted Campaigning for Brexit

After analysing where to find potential voters, Leave ran specifically tailored Facebook advertising campaigns to the identified personality groups. Where users on Twitter are able to customise their information settings, on Facebook this is more likely generated for you through the ‘filter bubble.’ Coined by Eli Pariser in 2011, this refers to the use of algorithms to show content that is reflective of a user's preference based on recent searches, location data, and past Internet behaviour.

Leave took advantage of the filter bubble to target advertising to specific groups of people from the data they had collected. This will be demonstrated through the examples of animal rights activists and youth voters.

These campaigns were generally provocative in nature and sought to target the individualistic fears of the audience. They did this through direct and indirect means.

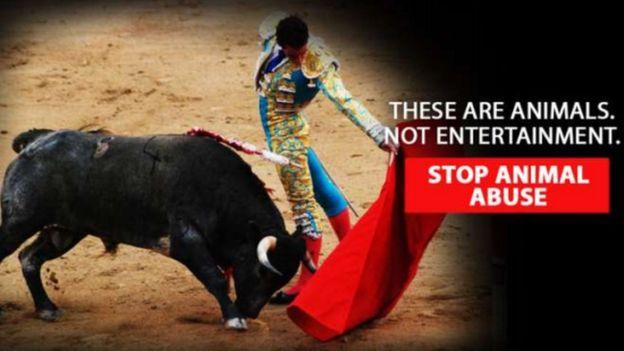

Example A – Animal Rights Activism

The first advertisement makes no specific mention of the Brexit debate but seeks to create a negative stigma toward other EU States. Drawing on the Spanish tradition of bull fighting, it attempts to distinguish the progressive animal protections that British people should advocate for from the celebrated behaviour of a fellow EU state. By subtly highlighting the differences between Spain and the UK, it proposes that the UK should not be politically, socially or economically aligned with the EU, because its member states hold values which are so different from its own.

The second advertisement is much more transparent in its message. It states clearly that the EU is preventing animal activism. It also implies that the EU is somehow at fault for violations towards these animals. The suggestion that the EU rejects and ignores the plight of the already voiceless in our world portrays the EU as a negative and harmful body for those invested in animal rights protections, regardless of the accuracy of these claims.

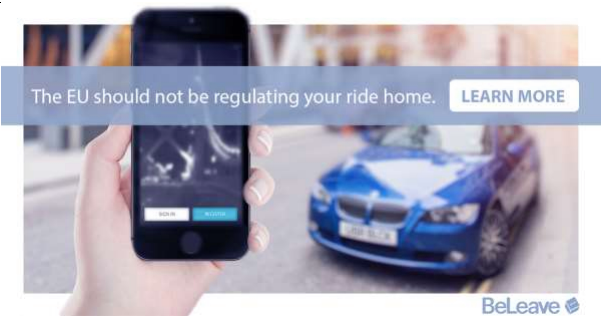

Example B - Youth voters

The following campaigns appealed to a younger demographic of the British public who traditionally vote along progressive rather than conservative party lines. These targeted ads sought Leave votes by appealing to young people's desire for and reliance on consumer technology. They suggest that the EU and its extensive regulations are impacting the services that individuals use in their everyday lives, and that this potentially infringes on individual liberty.

These show a direct form of advertising that was necessary to break down the indoctrinated progressive mentality that many within the 18-30 age block feel. The forceful words 'should not' project a clearly negative sentiment. This was coupled with the individual focus of these ads to show how much of a supposedly detrimental impact the EU has on individual's lives. .

Figure 4

The inaccuracy of certain facebook advertisements such as these was rarely accidental.

In the modern age, ‘politics exploits an information ecosystem designed for the dissemination of material which gives us feelings rather than information’ (Bell, 2016).

Without the professionalism required of a reputable media outlet, Facebook campaigning sought to target the emotional responses of potential supporters without fear of disrepute or condemnation. Leave also knew that this demographic was unlikely to question the factual accuracy of these advertisments, and instead question how the EU infringes upon their personal liberties.

Brexit as digital media effect

The 2016 Brexit battle was heavily influenced by the use of social media. The Leave campaign's victory demonstrated the pressing need to effectively use these online outlets to guarantee public support. The carefully orchestrated and inherently different approaches that Leave applied to Twitter and Facebook enabled the positive influence of prospective voters whilst harnessing the power and support of exiting voters.

References

Bastos M, Mercea D, Baronchelli A. (2018). The geographic embedding of online echo chambers: Evidence from the Brexit campaign. PLoS ONE 13(11): e0206841 (online).

Bauchowitz, S and Hänska, M. (2017) Tweeting for Brexit: how social media influenced the referendum (online).

Benoit, K and Matsuo, A. (2017). More positive, assertive and forward-looking: how Leave won Twitter (online).

Gerbaudo, P. (2014). Tweets and the Streets. Social media and contemporary activism. The introduction.

Maly, I. (2018). What is populism? A discursive take on the phenomenon.

Muller, JW (2016). What is Populism? Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Pariser, E (2012). The Filter Bubble.

Polonski, V. (2016) Impact of social media on the outcome of the EU referendum (online).

Silverstein, M. (2003). Communicating the Message vs. Inhabiting “Message”. From Silverstein, M. Talking politics. The substance of Style From Abe to ‘W’.

Usherwood, S. (2017). Sticks and stones: Comparing Twitter campaigning strategies in the European Union referendum (online).