Centenary of Poland's Independence

On November 11th 2018, Poland celebrated the centenary of its independence. This day did not go unnoticed in the global media, not only because of the magnitude of events (gathering about 250,000 people) but also due to the striking differences in commemoration styles between the attendees of the same march – the party in government and the New Right movements.

In this paper, I will briefly explain the events leading up to the march and the two sides at stake. With the use of digital ethnography I will analyze the image and message that those parties tried to convey, and the uptake of that message by global media.

The concept of a message as described by Silverstein (2003) conveys that it is dialogical, with messengers playing a crucial part in reproduction and uptake of the message, so that it will be read by the audience as it was meant. As a consequence, people will lead the message and it will mobilize them to share, comment, retweet etc. (Maly, personal communication, 2018).

Poland's Prior Independence Celebrations

The National Independence Day honours the restoration of Poland’s sovereignty from the German, Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires in 1918, which meant that Poland was back on the map after 123 years.

Almost every year in the last decade Warsaw’s (now) ex-mayor Hanna Gronkiewicz-Waltz tried to prohibit the march for safety reasons, saying that it could dominate the official celebrations, as it did in 2017, where violent nationalist protesters carried banners with xenophobic slogans such as ‘Pure Poland, white Poland!’

In response, president Andrzej Duda announced that the state will organize its own march, simultaneous with the nationalistic one. This time again, the court overturned Gronkiewicz-Waltz’s decision, resulting in an agreement between the government authorities and far-right organizations to conduct one march, where the state representatives would march first, and nationalist participants second, with the two entities separated by military police.

Independence March No. 1: the ruling party

Thank you for coming here, for Poland, and for bringing the white and red (Polish) flag which saw our fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers spill their blood. (…) There is space for everyone under our flags.

With those words president Duda set the stage for Sunday’s celebrations in Warsaw, and together with prime minister Mateusz Morawiecki, Law and Justice Party (PiS)leader Jarosław Kaczyński, and many other government officials, they walked in the ‘first’ march behind the Polish flag with a caption: 'For You, Poland' (Fig. 1). This slogan can be read as an instance of what Billig (1995) calls "banal nationalism," the nationalism that presents itself as 'normal, natural and just patriotic.'

For many, this event is an ideal point of departure for starting a debate about whether PiS faintly supports anti-Semitic and fascist organizations. Since gaining power in 2015, their Eurosceptic views, and recently, their efforts to take charge of Polish judiciary have weakened the country’s position in the international arena.

Furthermore, earlier that day during the official ceremony, the previously listed politicians kept Donald Tusk, president of the European Council, at a distance, even refusing to shake his hand.

Yet again, what was supposed to be a celebration of independence and commemoration brought Poland’s dissonance to the surface via highly contrasting images of the representatives of the right-wing ruling party and the head of the European Council, and versus the radical right organizations "in the back."

Behind the politicians and followers of the Law and Justice Party stood a cordon of Polish soldiers, who acted as a buffer to protect government officials and separate them from supporters of radical right movements.

Independence March No. 2: the Polish far-right

The attendees that constituted the second part of the Independence March (IM) highlighted their presence with red flares and flags of all kinds. Among thousands of ordinary citizens were far-right movements such as National Radical Camp (ONR), All-Polish Youth (MW) and the National Movement (RN) who have annually co-organized the event since 2010.

Although they often promote homophobic and racist slogans, this year’s march was much more peaceful compared to the 2017 events. But this does not totally exclude displays of xenophobia, which were incorporated into chants ('Use a sickle, use a hammer, smash the Red rabble.'), flags, balaclavas, and so on.

In opposition to PiS, the radical right representatives held a banner saying 'God, Honor, Fatherland' highlighting a hot nationalism, a nationalism that is recognized as combative and radical. Or , it could be understood as an anti-Enlightenment nationalism. Furthermore, they are involved in a metapolitical battle, which is an emic term describing their political actions claiming that if you want to change society, you should start with challenging common sense ideals rather than setting up a political party (Maly, personal communication, 2018).

In the following section, I will outline the main ideas of the aforementioned New Right and extreme right movements ONR and MW, and their most prominent contributions to the Independence March – including a brief analysis of their symbols and meanings.

National Radical Camp (ONR)

National Radical Camp (Obóz Narodowo Radykalny) is a far-right Polish organization founded in 1934 which propagates fascism, neo-Nazism, antisemitism, Polish ultranationalism, national radicalism, anti-communism and hard Euroscepticism among many other ideologies. ONR claims to be involved in many activities, ranging from organizing patriotic demonstrations, such as the Independence March, opposing leftist propaganda, working with veteran communities to organizing lectures and charity events like blood donations. The internal structure of the organization is dictated by geographical location, with one brigade in every province (a total of 16), and several branches abroad, in countries like Canada, USA, Switzerland, Norway, Spain etc.

We are Nationalists of the 21st century, so our goal is not historicism or sentimentalism, but continuous development and work on the revival of national and Catholic values. We do not want to stand by and complain - we want to take matters into our own hands.

Their recruitment strategy is based on the call to action. In his speech during the IM, ONR’s leader Tomasz Dorosz said: 'Our passivity and lack of involvement in national affairs means that minor organizations (responsible for gender projects like equality parades) make an impact and affect the fate of our country and the people, especially the young ones. Many Poles do not adhere to traditional values, because we are unable to defend them.'

Although there are no official statistics regarding the number of members since 2012 (highest attendance at the Independence March), the amount is constantly increasing. It is estimated that ONR could have up to several thousand members.

Recruitment at one of the biggest events organized by ONR.

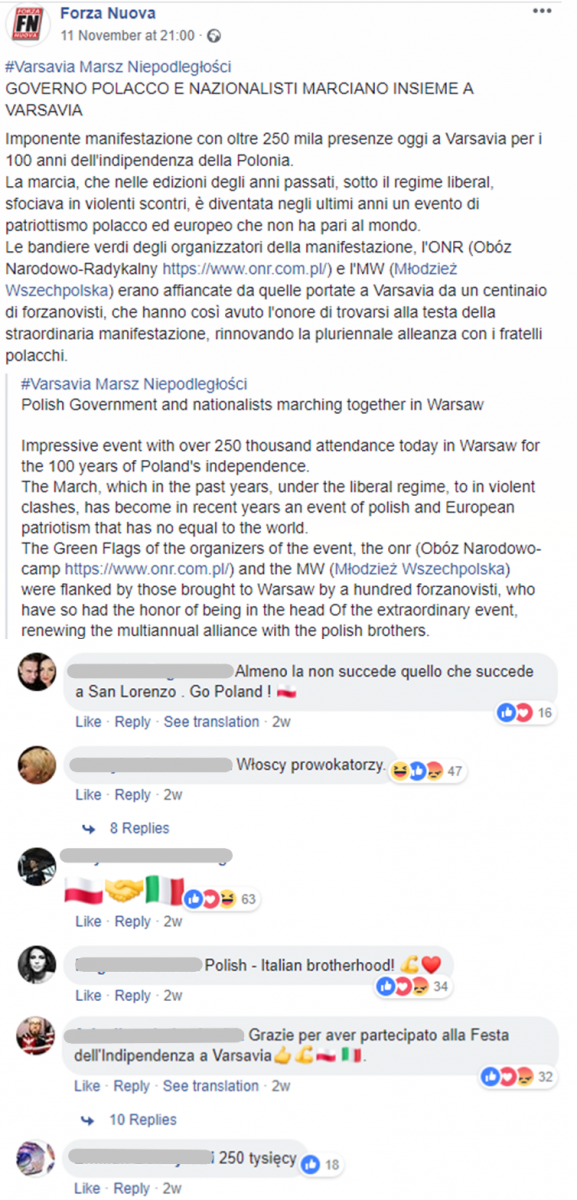

Moreover, an input from ONR that received a lot of media attention was inviting members of Forza Nuova, a neo-fascist movement from Italy.

All-Polish Youth (MW)

Another prominent movement present at the independence march was the All-Polish Youth (Młodzież Wszechpolska). According to Castells (2015), social movements are 'the producers of new values and goals around which the institutions of society are transformed to represent these values by creating new norms to organize social life.'

MW is a far-right organization that aims to raise young Poles in patriotic and Catholic spirit. Their ideology is very similar to ONR’s. In their manifesto from 1989, they claim to 'restore the moral and national renewal of the young generation by uttering war on the doctrines of arbitrariness, liberalism, tolerance and relativism.' On November 11th, surrounded by the smoke from the red flares, they burned the flag of the European Union and shortly after, posted it on Twitter.

EU flag burned. The crowds are shouting: Away with the European Union! #IndependenceMarch

Uptake of the message

By the evening, media outlets had published the run-down of events and their interpretation about the state of Poland’s democracy. Most of them arrived at the same conclusion – democracy is under threat.

The contrast between right-wing politicians (and lack of opposition present at the march labelled ‘For You Poland’), an overt display of nationalism by the radical right movements from Poland and abroad, and counter-demonstrators rioting for ‘Constitution’ form elements mixed and matched to generate headlines for the global news.

This gives them an opportunity for open interpretation, which lead to allegations such as one by a Croatian news channel claiming that the independence march was a 'gathering of extremists who demand ethnic cleansing in Poland.'

How the Polish far-right claimed Independence Day

All in all, Poland’s quite negative image abroad, as discussed in this paper, was heavily defended by Polish journalists, correspondents, and even ambassadors who tried to arrive at a factual summary of events, rather than a biased portrayal of the centenary's celebrations.

Both marches portray different sides of nationalism. According to Billig (1995), the first march is about banal nationalism - the nationalism that is hegemonic and thus comes across as natural and not harmful because it is normal to celebrate Independence as a nation. Such parades therefore reproduce, or in the words of Billig "flag the nation," and thus construct it culturally (ethnocultural nationalism).

The second march demonstrates hot nationalism (Billig, 1995), a nationalism that is explicit, radical and heavily politicized. It is the nationalism that we recognize as nationalism and as dangerous. In particular, this is an anti-Enlightenment blood-and-soil nationalism - one that is indicative of the most radical far-right anti-democratic fringes. Their participation in the march can be described as metapolitical, as battling for the normalization of their conceptualization of Polish nationalism and the Polish nation. The fact that (international) mainstream media portrayed the whole march as indicative of this group shows how their metapolitical strategy works.

References

Billig, M. (1995). Banal Nationalism. London: Sage Publications.

Castells, M. (2015). Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. John Wiley & Sons.

Silverstein, M. (2003). Talking Politics: The Substance of Style from Abe to "W". Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.