Disney's Mulan (2020) and Citizen Journalists: how digital media allowed feminists and Chinese people to reframe Mulan

Releasing a new version of Mulan in a super-diverse and digital world is a complicated matter. Not only do the producers risk 'othering' certain groups, but viewers from anywhere in the world can review the movie with their knowledge of certain niche topics the movie covers and convince people not to watch it.

In the age of modern technology—where we have supercomputers with cameras in our pockets—it's easy to underestimate the importance and relevancy of what millions of vloggers on the internet have to say. What makes them more special than the average person with a smartphone anyway? However, it's that reason that makes their voices all the more important to hear. Those with a following who speak out are representatives of niche groups.

In this article, two bloggers will be discussed who take up the role of citizen journalists on behalf of certain niche groups and their use of digital media to analyze and critique the new Mulan. The discursive strategies used to create discussion about Mulan 2020 and its unfortunate gaffes and how the affordances of digital media help spread the ideas of citizen journalists will also be reviewed. Finally, why this issue is relevant in today’s world will also be considered.

Disney's Mulan 2020: controversy in the making

October 2016 encountered the announcement of a lifetime for Disney fans: the company will be making a live-action remake of Mulan, a 1998 Disney classic that tells the story of Chinese warrior, Fa Mulan, and her devotion to her family and Imperial China. Fast forward to March 2020 and the world is hit with the biggest cinematic tragedy of the millennium.

The live-action adaptation of Mulan was one of the most anticipated films since its announcement—news companies did reports on it and fans speculated about the film for almost 4 years—yet it still became one of Disney’s biggest blunders for several reasons.

Preceding the release of the film a sequence of backlashes occurred that only became worse as its release neared. Mulan star, Liu Yifei, stated in August 2019 that she supported the Hong Kong police who were fighting against the pro-democracy protestors. Following Mulan (2020)'s release, people noticed that Disney thanked Xinjiang province for letting them film there; this was a marketing problem because Muslim Uyghurs are being detained in concentration camps in the area.

Then the cultural backlash came from ethnic Chinese people or people who are acquainted with Imperial Chinese culture. Historical fantasy author Xiran Jay Zhao addresses the cultural inaccuracies of the film in one of the most famous Mulan (2020) review videos on YouTube.

Finally, backlash arose from feminists about the misrepresentation of feminism in the film and how it only reinforced patriarchal ideals in both the fictional world of Mulan and the real world. This is addressed by blogger Madelaine Hanson’s article on the film.

Digital media and citizen journalists

According to Allan and Thorsen (2009), citizen journalism is “the spontaneous actions of ordinary people, caught up in extraordinary events, who felt compelled to adopt the role of a news reporter.” This means that anyone who reports on unusual events—in this case, the blunders of Mulan (2020)—and whose report is spread online could be considered a citizen journalist. We now live in a world of fast media, where everyone likes to have their content then and there. Due to this, citizen journalism is highly valued because of the 'authenticity' and 'realism' they bring to news stories. These come from the photos or live tweets of a certain event (Greer and McLaughlin, 2010). According to Castells (2009), the chances of ideas that challenge dogmatic values get higher with the extent of agency an individual has when posting these stories, which is relevant to the recognition of citizen journalism as a valid source of news.

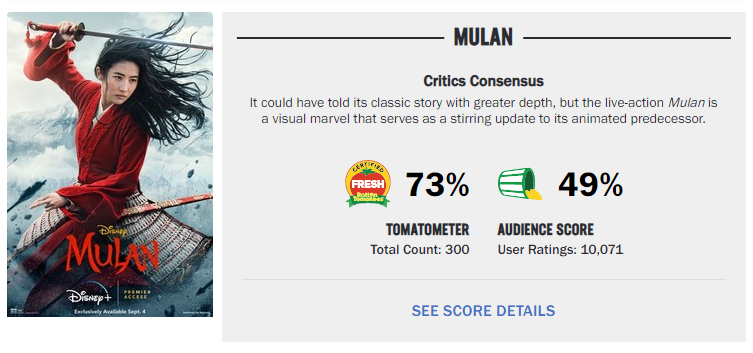

Traditional media initially interpreted and reported on news about the film from a well-established narrative of Disney making a live-action remake that would be a box-office success. This established narrative gave traditional movie critics a framework for their expectations and review of the film, which both were positive. This can be clearly seen in the discrepancy between the professional critic's response and the audience's response to the movie on Rotten Tomatoes.

Figure 1: Professional critic and audience response to Mulan (2020) in percentages

However, digital media platforms, such as blogs and YouTube, enabled citizen journalists to spread their opinions and reframe the film according to their own knowledge of the themes featured. Hanson and Zhao are the citizen journalists this article focuses on as they report on and give their own contribution to the reframing of the film based on the knowledge they have about feminism (Hanson) and Chinese culture (Zhao).

Their content challenged dogmatic ideas that are tied to Disney, challenging the notion of Disney advertising Mulan (2020) as an empowering feminist and culturally accurate interpretation of the 1998 classic. Hanson mentions in her article that she is one of the first people to see the film, which coincides with Greer and McLaughin’s (2010) idea that the immediacy in citizen journalism is connected to how the “evidence” of events is taken “as they happen”.

As more citizen-generated reviews came out on Rotten Tomatoes and Twitter, the initial general opinion on the film shifted to one that is overly negative. This new structure around opinions on the movie—created by citizen journalist content—thus shifted the focus of news media along with it, effectively reframing and reinterpreting the general consensus around the film.

The affordances of digital media help citizen-generated content to spread better than traditional media, and this comes from the interest of newer generations to not only consume news media but to also be involved in the production process (Allan and Thorsen, 2009). However, as powerful as reframing is, citizen journalists’ credibility is built upon an unstable foundation because they do not have the cultural authority to demand access to traditional news media (Allan and Thorsen, 2009). Assessing their performance and their use of the affordances of digital media is thus crucial in determining if bloggers have an impact and why they have an impact.

Feminist backlash

Right off the bat, Hanson proclaims herself as a feminist, saying “As a Bisexual Feminist™…” in her opening lines, asserting her authority to talk about the issues of feminist misrepresentation in the film. Her use of slang and informal language, which is apparent from the introduction of her article, gives her an air of authenticity, painting herself to be just another feminist who watched the film. However, she ironically calls the dialogue in the film “woke” and the film a “binfire”; this along with the lack of logos in her discourse makes her sound cocky, condescending, and not as knowledgeable in traditional feminism as she is in pop feminism.

Her way of highlighting her points comes in the form of repetition, where she frequently uses the phrase “super hot power genius” in the sentence “(Mulan:2020) is a super hot power genius warrior who has almost supernatural super hot power genius skills and er, remains an almost supernatural super hot power genius warrior.” Additionally, she uses hyperbolic vocabulary to stress the severity of the film’s missteps, calling it a “sanitized” remake that “…is aggressively anti-feminist”.

In terms of coding, Hanson heavily relies on ethos and pathos to argue why the film is bad. Appealing to ethos, she convinces people that she is “not one of those people who demands Disney answers to all feminist-genderqueer theory and sanitizes their screenplays accordingly…” (Hanson, 2020), in a show of relatability. She also speaks in the name of all women when she says that Mulan’s “strength was her own self belief, something all women can aspire to.” (Hanson, 2020). Finally, she uses pathos to evoke empathy from readers, as in her sentence “Even in the early 2000s, as a confused eight year old, that was a subtly comforting thing to see.” (Hanson, 2020). She also evokes empathy by explaining that Mulan from the 1998 film was empowering because she was just like any other woman; she had problems, she was misunderstood, but she ultimately overcomes those with determination and bravery.

Furthermore, Hanson often refers to dialogue in the film, as in the line “Every line of dialogue sounds like it was run past a team of lawyers to check whether it was ‘woke’.” (Hanson, 2020) and to scenes in the film as in the sentence “every scene has some contrived, jumbled forced comment on sexism or identity.” (Hanson, 2020) as material representations (Goodwin, 1994) to support her argument that the dialogue was heavily sanitized, as she would say, and that the scenes were nothing but pretty landscapes devoid of meaning.

However, Hanson fails to use facts to support her arguments and, compared to Zhao, she does not give suggestions as to how Disney could have represented feminism better. Additionally, the lack of a comment feature makes it harder for people to share their opinions on the article. Furthermore, the biting sarcasm and edgy humor of the author make it hard to take her seriously as a valid news source.

Cultural backlash

Zhao, compared to Hanson, is more prepared with her arguments for Mulan (2020)’s cultural inaccuracies. Much like Hanson, she informally gives her case, often using slang. However, her informality is much more welcoming than Hanson’s as it makes it easier to digest her content. As a historical fantasy author, Zhao is knowledgeable in Chinese history and this manifests itself in the way she speaks fluently about it. Evidently, as an ethnic Chinese person and a historical fantasy author, Zhao has the authority to speak about the issue of Mulan (2020)’s cultural inaccuracies.

Zhao highlights her points by comparing imagery from the film to real-life Imperial Chinese imagery. She compares Mulan’s makeup to what the makeup would actually look like—which is visually aided by her own photo of Imperial Chinese makeup—to show that, while the makeup is accurate, it is exaggerated for comedic effect. Though, on a more positive note, she applauds the film’s accurate architecture by comparing the capital city architecture in the film to real Imperial Chinese architecture of a building that is still standing today.

Figure 2: Comparison of Mulan's makeup and Imperial Chinese makeup

Figure 3: Comparison of Mulan (2020) building and real Imperial Chinese building still standing today

In regards to coding, Zhao expertly uses ethos and logos to support her arguments. Her use of ethos relies on the fact that she is ethnically Chinese rather than her credentials as a historical fantasy author; she knows a great deal about Chinese culture having grown up with it and she can spot the cultural inaccuracies Disney had put in the film. Immediately, she establishes the outsiders (Becker, 1997) in her video, referring to the white people who worked on the film and white people who don’t know anything about Chinese culture at large.

Additionally, she acknowledges different cultures within China but ultimately puts the nation under one label as in the quote “Mulan is not a character who was born great… The protagonists of Eastern stories […] work hard for their abilities.” Finally, she notably uses more logos compared to Hanson. She shows this by explaining and showing visual aid for Chinese cultural artifacts and traditions mentioned in the film to back her arguments up.

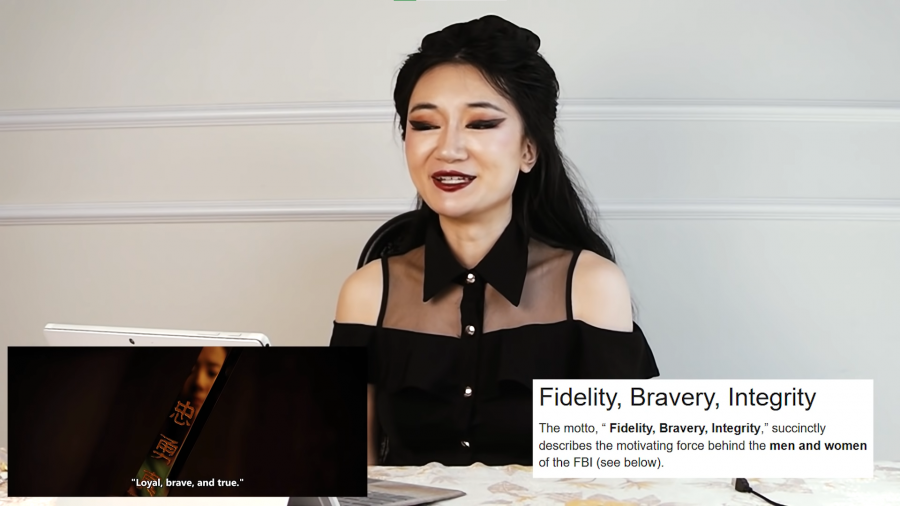

Helpfully, Zhao uses many material representations (Goodwin, 1994) to support her arguments. Throughout her video, she has videos or screenshots of the scenes she is speaking about on-screen so the viewers can understand the claims she is demonstrating. She also uses photos of Imperial Chinese artifacts when they are mentioned in the film, contending whether or not the film was accurate. At a funny juncture, Zhao shows the FBI motto, proving that the Chinese characters on Mulan’s sword are just a translated form of the FBI motto, which is culturally inaccurate because an Imperial Chinese sword would usually have a family name engraved on it.

Figure 4: Engraved sword of Fa family and FBI motto

As thorough as Zhao is, however, she does not always use direct sources or references when making her arguments, making it harder to fact-check and find out where she found her information.

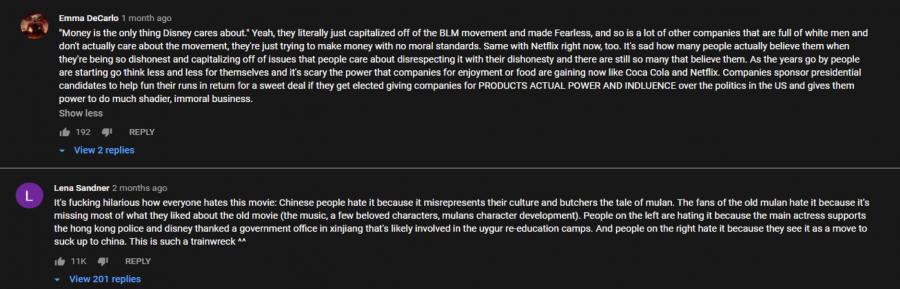

Finally, unlike Hanson, Zhao has the comment feature available in her video, allowing people to give their own reactions. The most common reactions were arguments that Disney is only making the film to profit off of superficial diversity (Figure 5) and—strangely enough—that Kung Fu Panda did a better job of being culturally accurate (Figure 6). In other ways, they reinforce the message that Zhao is producing.

Figure 5: Comments on Xiran Jay Zhao's video on Disney profiting off of the film

Figure 6: Comments on Xiran Jay Zhao's video on how Kung Fu Panda did a better job on representing Chinese culture

Hanson’s and Zhao's coding schemes

As analyzed in the previous sections, Hanson and Zhao managed to reframe Mulan (2020) from its original framework of being advertised as culturally accurate and empowering for feminists to a framework that suits their own culture, using the knowledge they’ve acquired from being part of cultural groups.

They’re able to do this by using coding schemes, which is a systematic method that puts worldly phenomena into categories that are relevant to the work of certain professions (Goodwin, 1994). In this case, Hanson’s and Zhao’s “profession” is being reporters of the film from niche cultures. A coding scheme establishes a perspective towards the world and puts phenomena in organized systems for professionals, which helps coordinate an organization (Goodwin, 1994).

According to Goodwin (1994), professionals use coding schemes to be able to narrow down the phenomena they are examining. By narrowing it down, it helps professionals to develop a data set of observations that can be compared to each other. In this case, Hanson’s looks at the movie from her idiosyncratic feminist ideals and beliefs as she frequently reminds her readers that she is a feminist, while Zhao’s data set draws from Chinese mythology and tradition. Hanson and Zhao evaluate and criticize the film based on the knowledge they have, effectively reframing the film to coincide with their cultural narrative.

Hanson frames the film as an instance of "cosmetic feminism" and not at all empowering (Hanson, 2020). Zhao, on the other hand, represents the ethnically Chinese people who felt that the film was culturally inaccurate and misrepresented the people and values of Imperial China. Similarly, the group identity of being Chinese and their familiarisation with Chinese culture and their shared language are what give them the opportunity to form discourse about the film.

Finally, in their niche, both have the cultural authority to speak out about the inaccuracies in the film, thus reframing the film from the advertised "culturally accurate" to culturally inaccurate. They reframe the film in a way that scorns the all-white writing staff of the film, considering the fact that it was advertised as a culturally accurate interpretation of the classic Chinese ballads. Therefore, these writers do not have the authority to advertise a film created by white people as culturally diverse.

So what now?

As it is, the synthesis of the feminists' and the ethnic Chinese people's dissatisfaction with the movie only goes to show that Hollywood should be more careful when producing and advertising their films as "empowering" and "culturally accurate" by making sure their films actually meet these standards and that they have staff from the groups they are trying to portray. Madelaine Hanson's and Xiran Jay Zhao's use of discursive strategies in their reactions to this movie is extremely important to understand how non-professionals can use digital media to reframe the meaning and quality of a film. This is important because not only are they representing large groups of people, but they are also trying to argue against the questionable moves of a multibillion-dollar company. Zhao makes good use of discursive strategies in her video, garnering the attention of fans and even storyboard artists from the 1998 movie. However, Hanson fails to use these strategies properly, making her article not as strong as Zhao's video. Just because bloggers and vloggers do not a priori have this cultural capital as mainstream journalists, we see the importance of their discourses in the overall impact they will have.

The relevancy of this topic lends itself to the fact that citizen journalism has been on the rise with the upsurge of the internet's and technology's ease of access. People can make their own blogs and YouTube videos on the things they find important, creating a more diverse pool in digital media because these types of content are not as moderated as a news article or a piece in Time magazine. With regard to films, it is also relevant to speak about the fact that marginalized communities should be represented properly in films. In a time of hyper-globalization, it's favorable for companies to diversify their community, however, they tend to do this poorly because some of them diversify for the sake of diversity instead of diversifying to bring new ideas to the table. As in Hollywood, they've come a long way and diversified acutely since Mr. Yunioshi's appearance in Breakfast at Tiffany's, but they've still got a long way to go.

Figure 7: Mickey Rooney as "Mr Yunioshi" in Breakfast at Tiffany's

References

Accented Cinema. (2020, September 10). Mulan: A Case of Failed Empowerment | Video Essay. YouTube.

Allan, S., & Thorsen, E. (2009). Citizen Journalism: Global Perspectives (Global Crises and the Media) (First printing ed.). Peter Lang Inc., International Academic Publishers.

BBC News. (2020, September 8). Disney criticised for filming Mulan in China’s Xinjiang province.

Becker, H. S. (1997). Outsiders: Studies In The Sociology Of Deviance (New edition). Free Press.

Blommaert, J., & Verschueren, J. (1998). Debating Diversity: Analysing the Discourse of Tolerance. Routledge.

Cameron, D. (2001). Working with Spoken Discourse (1st ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Castells, M. (2013). Communication Power (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Chow, A. R. (2020, March 2). Here’s What to Know About the Mulan Boycott. Time.

Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional Vision. American Anthropologist, 96(3), 606–633.

Greer, C., & McLaughlin, E. (2010). We Predict a Riot?: Public Order Policing, New Media Environments and the Rise of the Citizen Journalist. British Journal of Criminology, 50(6), 1041–1059.

Hanson, M. (2020, September 7). Hot take: Mulan (2020) isn’t feminist, empowering or inclusive. Medium.

hiou d. (2020, December 16). Mulan - Audience Reviews. Rotten Tomatoes.

Jin L. (2020, December 14). Mulan - Audience Reviews. Rotten Tomatoes.

Mulan (2020) Cast and Crew. (2020). IMDb.

Rappler. (2019, December 29). Rappler on Female-led Superhero Movies in 2020 [Tweet]. Twitter.

Rotten Tomatoes Editorial. (2021, January 18). Mulan (2020).

South China Morning Post. (2020, September 18). Understanding Mulan: controversy, culture, feminism and China. YouTube.

Talusan, R. (2020, September 17). Disney’s “Mulan” Remake Just Reinforces the Patriarchy. Bitch Media.

Tian, A. T. (2020, September 22). Mulan: A critical look at its portrayal of feminism and Chinese culture. Cold Tea Collective.

Xiran Jay Zhao. (2020, September 11). EVERYTHING CULTURALLY WRONG WITH MULAN 2020 (And How They Could’ve Been Fixed). YouTube.