Divine data: how the Co-Star astrology app becomes an expert on ‘the unknown’

It is 11:00 AM and my phone abruptly vibrates twice. I look over to my screen. “Your day at a glance:…”, the notification tells me, “…how do you handle disappointment?”. My fingers linger over the screen for a few seconds until I give in and click the message. Despite receiving a different yet equally ambiguous notification from the Co-Star astrology app every day, I still find myself frequently opening it to read what else it has to say to me. Having downloaded the app out of curiosity after seeing my friends use it, persuaded by what feels like a way of getting to know yourself and others better, I still objectively know I am merely interacting with an algorithm that claims to have insights about me that I could never have access to on my own.

Yet there is something about the way Co-Star seems to convince users of its expertise on mysterious, unknown matters and its ability to translate these matters into concrete, bite-sized pieces of information. But what exactly makes Co-Star appear like such an accurate app despite its pseudoscientific foundation? To help answer this question, this article explores the discursive strategies and, in turn, the semiotics of expertise as identified by Carr (2010) which can be found in the astrology app Co-Star.

Co-Star and “Hyper-personalized astrology”

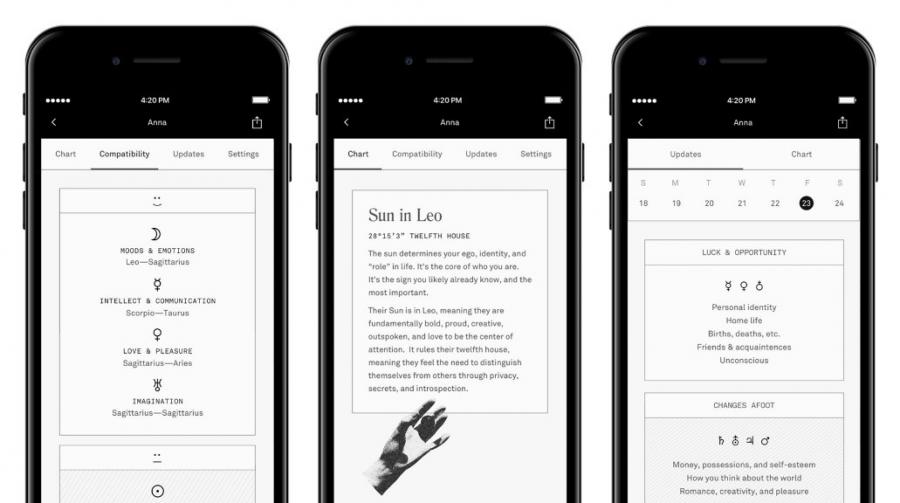

Co-Star was launched in 2017 by CEO Banu Guler and her coworkers Anna Kopp and Ben Weitzman, after Guler had come up with the initial idea (Noble, 2019). After first installing the app, users are asked to fill in not just the date of their birth – which is what many horoscopes focused on – but also the place and time. This generates their natal chart (see Figure 1), which shows the supposed location of each planet as well as the sign and house in which it appeared when the user was born. According to Co-Star, this natal chart can reveal personal characteristics such as “character traits, behavioral tendencies, hidden desires, and the directions your life might take.” (Co-Star, n.d.).

Figure 1. Example of a natal chart generated by Co-Star

Besides this, Co-Star also shows insights based on users’ behavior in the app itself; They will see more insights about the specific aspects they spend the most time looking at. Additionally, the app also allows users to add friends and see their natal charts, daily updates, and their compatibility in areas such as emotions, communication, and love (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Comparing friends’ charts to your own

These insights, presented in a minimalistic black-and-white table, are based on what Co-Star claims to be “a complete picture of the sky”, generating “hyper-personal” horoscopes based on information about the user’s birth (Co-Star, n.d.). This way, Co-Star differentiates itself from other sources of astrological insights: where other sources are framed as superficial and vague, Co-Star puts users’ daily lives in context of the vast universe.

Where other sources are framed as superficial and vague, Co-Star puts users’ daily lives in context of the vast universe.

The app’s interface is a manifestation of this claim: the use of charts for data visualization – generally used to help understand large quantities of data – paired with fixed categories in which various areas of life can be divided, the app renders its astrological insights almost as something scientifically proven. With this format, the app claims to bring about a level of clarity, meaning, and connection to ourselves and to others, in a world in which “screens shape our daily lives” (Co-Star, n.d.). Ironically, of course, the user needs a screen to do so.

Expertise through authentication and evaluation

Things that are widely accessible though arguably illegible, like a natal chart based on one’s birth information in this case, provide an opportunity to enact expertise by being “expertly translated by those who claim to have special knowledge of them.” (Carr, 2010, p. 22). This process of authentication and evaluation is one of the constitutive processes of expertise described by Carr (2010). In this case, a certain authenticity is ascribed to the app – mainly hinging on the ‘completeness’ of its data in comparison with other astrology resources – as well as certain qualities, such as bringing meaning and much-needed order in a chaotic world. In other words, it establishes an interpretive frame through which the app and its discourse should be viewed. In doing so, hierarchies and distinctions are created not only in relation to other astrological resources, but in relation to people as well.

According to Co-Star, those who do not engage with astrology on a daily basis might miss out on a touch of “mystery” and “magnitude” in their otherwise “clinical” and “confusing” reality.

While one can argue that the insights Co-Star provides are still highly ambiguous, the app seems to render users as individuals who, thanks to the app, live their lives with a certain level of awareness, mindfulness and understanding of experiences that cannot be explained. Those who do not engage with astrology on a daily basis might miss out on a touch of “mystery” and “magnitude” in their otherwise “clinical” and “confusing” reality (Co-Star, n.d.). As Noble (2019) argues after having used the app: “Whether it was real or not, I had something that could give meaning to the chaos around me.” This shows how two types of people – experts and laities (Carr, 2010) – are identified in relation to the object that is Co-Star; those who use the app are knowledgeable and aware on a more accurate and elite level than those who use any other app or source – creating a hierarchy within the astrology community. Additionally, those who do not seek astrological insights at all are the ultimate, less-aware laities. Co-Star’s expertise emerges here, too, as it positions itself as the most knowledgeable – perhaps even all-knowing – actor in this relationship.

Using AI terminology

To claim that an app can generate all these personal insights which pass for ‘real’ knowledge is quite a bold statement to make, although such claims are generally habitual in astrology as a whole; these insights and their accuracy are often supported with mathematical discourse. One astrology blog, for instance, describes how “your birth chart is a mathematical model of your character and the rules of astrology allow you to calculate and forecast your character’s reaction to circumstance.” (Astrology for aquarius, n.d.). Similarly, Co-Star supports their expert position using discourse on quantifiable data which, in this case, is heavily focused on terminology used in Artificial Intelligence. Both in-app and on their website, Co-Star uses a specific register to render astrology as something tangible, and itself as the ultimate expert on these ‘tangible’ insights. Such an expert register is more specifically defined by Carr (2010) as “a way of speaking that is recognized as a special kind of knowledge and manifests in interaction as such.” (Carr, 2010, p. 20). The discursive processes that represent these astrological insights are extremely important, as they form the basis on which Co-Star can be evaluated as an expert on a culturally valued object (Silverstein, 2004, 2006, as cited in Goodwin, 2010).

Co-Star speaks of the universe through a digital lens, as if it were a chaotic, colossal assemblage of data, positioning itself as “a key for decoding the cosmos”.

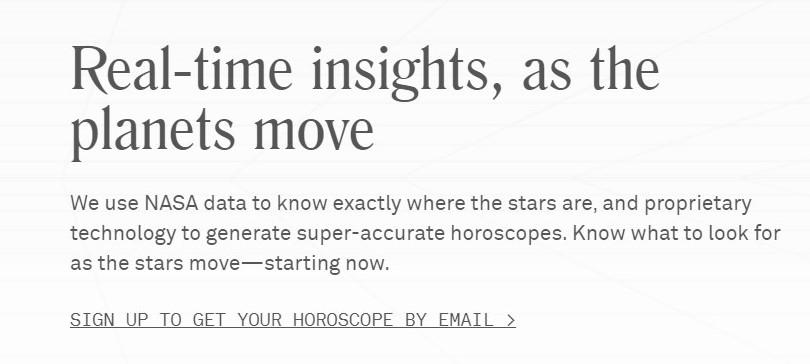

Thus, while Co-Star describes astrology and its characteristics as mysterious and supernatural, it speaks of the universe through a digital lens, as if it were a chaotic, colossal assemblage of data, positioning itself as “a key for decoding the cosmos”. A lot of this has to do with how the app works, as it is “powered by AI that merges NASA data with the insight of human astrologers.” (Co-Star, n.d.) – another statement supporting their claim of being the most accurate source for astrological insights (see Figure 3). Co-Star does not only derive its data from the scientific field of astronomy, but some of its discourse as well; Where NASA describes it as their mission “to understand our place in the universe” (NASA, n.d.), Co-Star, in a similar fashion, aims to “find our place in the universe” (Co-Star, n.d).

Figure 3. “Real-time insights, as the planets move.”

This discursive strategy speaks to another one of the constitutive processes of expertise which is described by Carr (2010) as institutionalization. Co-Star adopts institutionally authorized ways of speaking by using ‘AI language’ to signify expert enactments. These technical terms – generally used by members of professions concerned with AI and data analysis – originate from an interpretative framework, or, in Goodwin’s (1994, as cited in Carr, 2010) words, a professional vision through which the app’s insights are expertly translated. As Mehan (1996, as cited in Carr, 2010) suggests, such technical terms can give this discourse a privileged status precisely because it is so ambiguous and therefore unlikely to be the subject of potential challenges.

Thus, Co-Star deploys recognizable features from AI terminology as a specific genre, a concept described by Konnelly (2020, p. 70) as “constellations of co-occurrent linguistic elements and structures that define or characterize particular classes of utterances” (p. 70). In doing so, Co-Star attempts to attach to itself the social meaning and (academic) status associated with the genre of AI terminology.

Quantified self-knowledge and surveillance failures

These discursive strategies are not only used to come across as an expert, but it is also part of a strategy to convince users to share their data – a strategy described by Jones (2020) as ‘pretexting’. The Co-Star app can essentially be seen as a self-tracking technology in the way that it attempts to find patterns based on personal details, AI, and user data, before reporting these findings back to the user. The app differs from other self-tracking devices in that it explicitly claims not to sell user data to third parties (although it does provide the option to connect your account to Facebook) and claims to only profit from in-app purchases.

The Co-Star app can essentially be seen as a self-tracking technology in the way that it attempts to find patterns based on personal details, AI, and user data, before reporting these findings back to the user.

Still, it reflects what Crawford, Lingel, and Karppi (2015) describe as “the simultaneous commodification and knowledge-making that occurs between data and bodies" (p. 479) which positions not individuals, but tracking devices as the most authoritative sources of self-knowledge (Crawford et al., 2015). Co-Stars’ promise is to communicate the complexity of a user’s personality using astrology. Its discourse is very similar to that of wearable devices, in which its own technology is presented as something “radically new”, able to “reflect back the ‘real’ state of the body” (Crawford, et al., 2015, p. 480). Co-Star goes beyond the physical, claiming to “illuminate the unknown” which the user supposedly needs in order to have meaningful connections and conversations with others (Co-Star, n.d.). For many users, such as the one in Figure 4, Co-Star is indeed seen as the ultimate guide on their own selves.

Figure 4. “…the general guidance I have been able to access easily each has been so helpful”

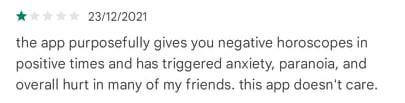

For others, however, it is doing the exact opposite. The reviews of both users shown in Figures 5 and 6 shed more light on negative experiences with the app, describing how it has triggered negative emotions. For them, the documented results of their monitoring do not accurately capture and represent themselves. This likely has to do with the way in which user data is entextualized by the app and what it decides to show or not show, illustrating the issue of power between Co-Star and its users (Jones, 2020).

Figure 5. “This app doesn’t care”

Figure 6. “…that’s not just snark, that’s meanness and emotional manipulation.”

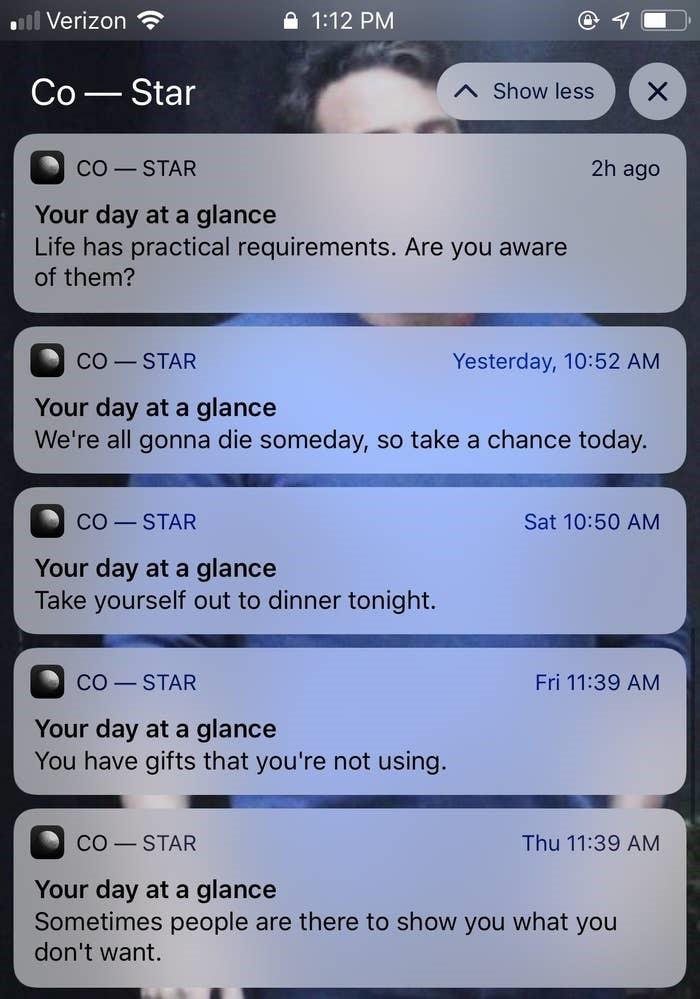

Co-Star CEO Guler has noted that the app’s daily notifications to users are not only meant to bring positive, inspirational insights (Guler, 2021 as cited in Vilog, 2021). Still, many users have voiced their discontent with the frequent, ‘edgy’ notifications they were receiving, like those in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Examples of ‘edgy’ Co-Star notifications

This goes to show that, while claiming to generate insights with the help of human astrologers, the inferences formed by Co-Star’s algorithm – partly based on the often widely relatable characteristics of astrology signs, and partly on the assumptions of those who have written and trained the algorithm – do not always get it right. In the end, the mystery and magic of Co-Star’s fortune-telling are probably, for a large part, the result of predictive inferencing based on the probability of future user behavior (Jones, 2020).

The mystery and magic of Co-Star’s fortune-telling is probably, for a large part, the result of predictive inferencing based on the probability of future user behavior.

Co-Star and Expertise

At first glance, the astrology app Co-Star seems like the ultimate, pocket-sized tool to know the unknown, uncover secrets of the universe, and identify your place in it. Users are persuaded to fill in details of their births to the minute, in the hopes of letting the app fulfill promises of self-knowledge, meaningful connection, and a sense of order in a chaotic world. Claiming to generate hyper-personal insights like no other astrological source, Co-Star strategically uses discourses from the fields of AI and astronomy to further enact their expertise on users’ personal lives in relation to the stars. The mixed responses to Co-Star’s generated insights, however, illustrate how its workings are not more different or mysterious than other tracking technologies.

References

Astrology for Aquarius. (n.d.). Mathematics, measurement and astrology.

Carr, E. S. (2010). Enactments of expertise. Annual Review of Anthropology, 39, 17-32.

Co-Star. (n.d.). About.

Co-Star. (n.d.). Frequently asked questions.

Crawford, K., Lingel, J., & Karppi, T. (2015). Our metrics, ourselves: A hundred years of self-tracking from the weight scale to the wrist wearable device. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 18(4-5), 479-496.

Jones, R. (2020). Discourse analysis and digital surveillance. In A. De Fina & A. Georgakopoulou (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Discourse Studies (pp. 708-731). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Konnelly, L. (2020). Brutoglossia: Democracy, authenticity, and the enregisterment of connoisseurship in ‘craft beer talk’. Language & Communication, 75, 69-82.

NASA. (n.d.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Noble, A. (2019, September 6). What’s Co-Star? Meet the astrology app that’s intriguing millennials everywhere.

Vilog, D. (2021, January 10). People have had enough of Co-Star Astrology’s edgy humor and ‘trolling’.