Eurovision as a platform for international politics

When you read "Eurovision Song Contest", or ESC for short, you probably immediately think about lots of glitter and glamour, and maybe about a woman with a beard too. But what probably doesn't spring to mind is the hidden (and not so hidden) political statements often made within the contest. This article will focus on the political aspects of the ESC and what these have to do with the concept of identity.

What is the contest about?

The Eurovision Song Contest is an annual song competition in which most European and some non-European countries compete. There are two semi-finals and a final, all broadcasted on live television, in which the artists representing the countries often perform with over-the-top outfits and songs.

After everyone has performed, people living in one of the competing countries can use their (mobile) phone to vote for the country they liked best (except for their own). By the end of the night, one country is the winner and it is expected to host the contest the next year. For the contestants, the ESC can serve as a perfect opportunity to promote their country since the show is watched by around 200 million people around the world (BBC, 2018).

Eurovision final

How it all started

The first ESC took place on the 24th of May 1956 with the aim to reunite Europe after the first and second world war (De Bruijn, n.d.). It was established by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU). At first, only 7 countries competed in the contest.

Now the contest has grown to include as many as 43 countries, some of which are not members of the European Union (BBC, 2018). Especially after the end of the Cold War, the number of competing countries increased with many former Eastern Bloc countries wanting to join (Eurovision, n.d.b).

The ESC is not just some European contest, but a phenomenon of globalization, connecting millions of people around the world with songs, performances and artistic expression of all sorts.

This might leave you wondering: why are non-European countries competing in a European contest? This is because the EBU, the broadcaster of the ESC, includes members not only from European networks but also from outside Europe. Every country that is a member of the EBU is eligible to take part in the contest. This is why countries such as Israel and Azerbaijan also participate nowadays (Jordan, 2014).

The only exception to this rule is the participation of Australia. Australia is not a part of the EBU but was invited by the EBU as a one-time guest contender for the 60th birthday of the ESC in 2015. At the end of 2015, it was confirmed that Australia was permitted to participate in the contest as an official competitor for the following years too (Eurovision, n.d.a; Lam, 2018).

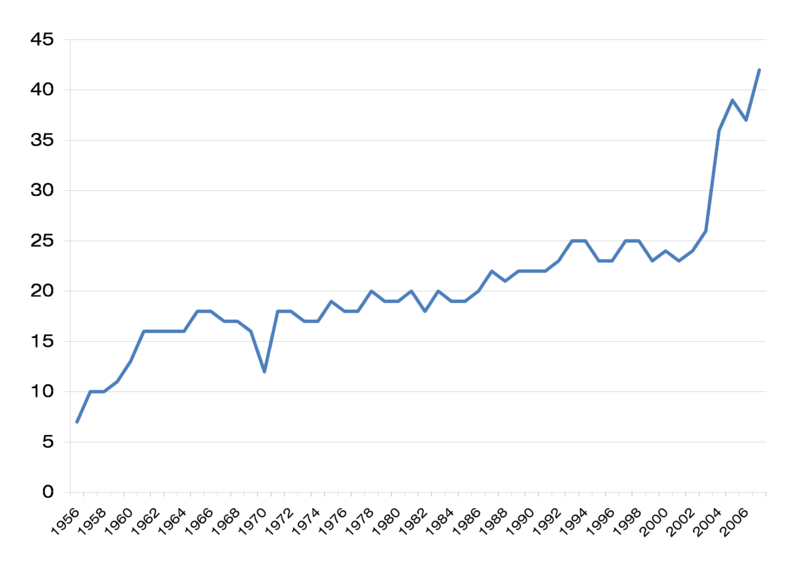

Amount of countries competing in the ESC per year

By now, I think you would agree that the ESC is not just some European contest, but a phenomenon of globalization, connecting millions of people around the world with songs, performances and artistic expression of all sorts. However, culture is not the only thing connecting people in the ESC; politics also play their part.

Eurovision and politics

Although the ESC is officially not seen as a political event, politics were part of it since its beginning: the contest was established with the aim to unite Western European countries as a unified bloc during the Cold War (Fricker & Lentin, 2009). Another example of early political influence in the ESC is the participation of Yugoslavia from 1961 onwards as the only non-Western European country. Their participation can be seen as a political statement of refusing to submit to Soviet dominance (Vuletic, 2007).

Not only does the ESC as a contest itself have political roots, but political influences are also visible within the contest. According to the rules of the ESC, political statements in either lyrics, speeches or gestures are forbidden and can result in countries being disqualified. However, this doesn’t stop countries from making such statements (Eurovision, n.d.c.).

In the past, political statements have been made by various contestants in more or less obvious ways. Whether the message was related to their own country, another country or a taboo they wanted to address, political statements were allowed into the contest. In the end, it is always up to the organization of the ESC to determine whether something constitutes political expression or not.

Breaking taboos

Some of the most memorable ESC performances of the last few years were used to break widespread taboos. I think nearly everyone who watches the ESC will remember Conchita Wurst, mostly remembered as "the woman with the beard". Conchita Wurst performed her song "Rise Like a Phoenix" for her country Austria. Her aim was to spread the message that everyone can be who they want to be and look the way they want to look (Nicolasen, 2014).

Outside the ESC, Conchita is Tomas Neuwirth. In 2014, he adopted the identity of "the woman with the beard" for the ESC. This identity became a symbol for the acceptance of LGBT individuals around the world. The act got "douze points" (or 12 points, the highest score possible) from many countries and won the ESC that year.

New Statesman (2014) also considered Conchita's win to be a sneer at Russia as the country is known for their intolerance against the LGBT community: “a vote for Wurst is another vote against Russian homophobia and transphobia, and a win would send out a strong message of defiance eastwards”. With her new identity, Conchita made a contribution to the global debate about ensuring human rights for the LGBT community.

Conchita wurst wins the ESC

Country politics

In some cases, Eurovision political statements were too obvious in a negative sense, which made the organization of the ESC decide to disqualify the country. Such was the case of Georgia's entry in 2009. Their song "We Don’t Wanna Put In" was interpreted by most as the Georgians making fun of Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin (Marcus, 2009).

At the time, Georgia’s relationship with Russia was tense due to a conflict that had started a few months earlier. The conflict concerned South Ossetia, a separatist region of Georgia. Russia accused Georgia of sending soldiers to the region while Georgia accused Russia of provoking a war by sending troops, tanks and armored vehicles to the area (Trouw, 2008).

"We don't wanna put in the negative move, it's killing the groove"

The relationship between the countries never really improved, which can be seen in the lyrics of Georgia’s song. One part of the lyrics stood out in particular: "We don’t wanna put in the negative move, it’s killing the groove" was considered a clear jab at Putin. Georgia reacted to the controversy by arguing that the song should be seen as a harmless joke. In this way, the Georgian team behind the entry temporarily framed their identity as that of "the funny one", which backfired as everyone knew about the country's conflict with Russia.

The organization of the ESC didn’t believe their argument of being "just funny" and demanded that Georgia change their lyrics or enter another song. Georgia refused to do this and chose to withdraw from the competition (Marcus, 2009).

Less obvious politics

Still, some instances of political expression seen in the past didn’t lead to disqualification. In these cases, the political statements were present but not obvious enough to lead to a disqualification.

An example is the song "1944" by Jamala, who represented Ukraine in 2016. The official interpretation states that the song is about the singer's grandmother who lived in the Crimean region in Ukraine and was deported by Russia in 1944. This song brought up a sensitive topic for Russia since they had recently annexed the Crimean peninsula and saw a clear connection between the song and their actions. The Ukrainian singer stated that the song was just about a family tragedy and since the organization of the ESC saw no explicit textual references to the present annexation of Crimea, the song was not disqualified (Belgers, 2017).

In fact, the song won the contest that year. Although the organization of the ESC didn’t note explicit textual references, implicit references were definitely there. Already in the first sentences of the song, where Jamala sings "When strangers are coming, they come to your house. They kill you all, and say: we’re not guilty", the song can be interpreted as referring to the annexation of the Crimean peninsula by the Russians and how they claim they are not guilty.

Even Jamala herself admitted to The Guardian (Stephens, 2016) that her song was not just about family history: “Of course it’s about 2014 as well. These two years have added so much sadness to my life. … What am I supposed to do: just sing nice songs and forget about it? Of course I can’t do that.” So, to the ESC, Jamala is a woman innocently singing about a family tragedy, while outside the contest the singer reveals her resentment for Russia's actions explicitly.

Jamala wins the ESC

Ukraine and Russia

Jamala's 2016 song was not the first time Ukraine and Russia made political statements against each other in the ESC. In the past, multiple "hidden" actions were taken by the countries. In 2005, Ukraine tried to enter the unofficial anthem of the orange revolution into the competition, which the Russians saw as an attack on Putin. The song was not accepted by the ESC organization (De Bruijn, n.d.). Two years later, Ukraine entered another song that was not appreciated by Russia. Ukrainian drag queen Verka Serduchka sang the line "Lasha tumbai" in her song multiple times, which sounds like poorly-pronounced English for "Russia goodbye".

In 2017, the year Ukraine hosted the ESC after winning with Jamala's song the year before, another Russia-Ukraine incident occurred. Russian singer Samojlova was not allowed to enter Ukraine since she performed in Crimea without a special visa, a year after Russia annexed the area.

Because of this performance, Samojlova was put on Ukraine's blacklist and got a travel ban (Belgers, 2017; De Bruijn, n.d.). The EBU tried to resolve the problem by offering Russia a satellite connection to broadcast their performance from their own country, but this offer was rejected by both Ukraine and Russia. Ukraine didn’t want to broadcast the performance of a lawbreaker and Russia thought that performing via a satellite connection was not in line with the ESC spirit. In the end, Russia decided to withdraw from the competition (Belgers, 2017).

The ESC is deeply connected to political issues and it is often used as a platform for people and countries to make political statements.

After Russia's decision to withdraw from the competition, some even thought that this was the country's plan all along. In an article in the Dutch newspaper Trouw in 2017 (Belgers, 2017), it was argued that Russia didn’t even want to compete that year in the first place and acted in this way just to look good at the expense of Ukraine. The Russian team could have known that the singer they signed up would probably get a travel ban. Besides, according to the article, they hadn’t even booked a hotel, something that is normally taken care of as soon as the candidate is announced. With Ukraine banning the Russian singer, who is also disabled, it looks like Ukraine is just being awful with no good reason; how could a singer with a disability be dangerous? Of course, we will never know the truth of the matter for certain.

Just like in the other political statements made in the ESC, a temporary identity change can be witnessed in this discussion. Everyone knows Ukraine and Russia are not best friends, but for the ESC, they both try to appear to be "innocent" countries with no political tension between them. They go from openly hating each other in daily life to acting innocent in the ESC, even though everyone knows their identity outside the contest is different.

Political statements in other contests

As has become clear so far, the ESC is deeply connected to political issues and it is often used as a platform for people and countries to make political statements. But the ESC is not the only global contest that is affected by politics. For example, the acceptance of Kosovo by the international football federation FIFA in 2016 caused a lot of resistance from Serbia. In 2008, Kosovo declared their independence from Serbia, but nowadays most Serbians still don’t accept Kosovo as an independent country (Nazar, 2018). Kosovo eventually did not qualify for the 2018 world cup. Still, their rivalry with the Serbian team became evident when the Swiss team, which includes two Kosovar-Albanian players, ended up in the same pool as Serbia in the group phase of the 2018 world championship (Nazar, 2018). As you can probably imagine, the match between the two countries was interesting.

Instagram Shaqiri (one of the Swisse players)

A month before the match, the conflict had already started. One of the Kosovar-Albanian players on the Swiss team posted a picture of his shoes on Instagram, showing one football shoe featuring a Swiss flag and the other a Kosovar one. He later stated that he had no political intentions in sharing the post and that he just wanted to show his loyalty to both countries. However, many Serbians saw the post as a provocation (Ames, 2018). By posting this picture, the player constructed his identity as if it was defined not only through his belonging to Switzerland and the Swiss team but also through his Kosovar roots. Maybe his intentions were not to provoke Serbia, but by showing that he literally carries Kosovo with him on the football field, an implicit message to Serbians was clear. This incident shows that constructing one's identity in a specific way in the context of an international contest can have unintended political consequences.

During the match itself, a second incident occurred. The Kosovar-Albanian players celebrated their goals by portraying a double-headed eagle with their hands, which points to the Albanian flag. Much like Kosovo, Albania is still at odds with Serbia. Just as in the Instagram post, this sign refers to the identity of both players. They are not just Swiss (and Kosovar), but Albanian as well. Where the political statement in the Instagram post could have been unintended (maybe the player just wanted to show the world that he’s looking forward to the world cup), this statement was more explicit. Both players showed a sign portraying their Albanian identity, right in front of the Serbian players and crowd. Serbia was offended by the sign and FIFA agreed that making the sign was unsportsmanlike. In the end, it was decided to give both players a fine of ten thousand Swiss Francs (NOS, 2018).

Kossovar-Ukrainian-Swisse players Xhaka and Shaqiri

Of course, this is just one of many examples of political statements being made within global or continental contests. Some of them are seen as positive, while others have a negative load attached to them. Further examples include the kneeling NFL players, the Egyptian judo player who didn’t want to shake hands with his Israeli opponent in the 2016 Olympics, and the Croatian President who wore the shirt of the national football team during their matches in the World Cup.

Identity as a part of political statements

This article shows that in the case of the ESC, contestants often opt to adjust their identity to be able to make political statements. Since they are not allowed to make political statements explicitly, they have to hide behind a different identity. This way, their real identity (e.g., that of hating another country) becomes "hidden" and their political statements become implicit. Still, because everyone knows about their identity outside the ESC, the implicit meaning of their political statements is clear to the rest of the world.

With the 2020 ESC cancelled, we can only wait and see what 2021 will bring in Eurovision politics.

References

Ames, N. (2018, June 21). Shadow of Kosovo hangs over Switzerland’s crunch tie with Serbia.

BBC. (2018). What is the Eurovision Song Contest?

Belgers, J. (2017, May 8). Wilde Rusland wel naar het songfestival in Kiev?

De Bruijn, T. (n.d.). Het Eurovisie Songfestival: glamour, controversie en schandaal.

Eurovision. (n.d.a). Australia.

Eurovision. (n.d.b). In a nutshell.

Eurovision. (n.d.c). Rules.

Fricker, K., & Lentin, R. (2007). Performing global networks. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Jordan, P. (2014). The modern fairy tale: Nation branding, national identity and the Eurovision song contest in Estonia. Tartu: University of Tartu Press.

Lam, C. (2018). Representing (real) Australia: Australia’s Eurovision entrants, diversity and Australian identity. Celebrity Studies 9(1), 117-125. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2018.1432354

Marcus, S. (2009, March 11). Georgia pulls out of Eurovision after controversial song is banned.

Nazar, M. (2018, june 22). Emotionele avond in aantocht voor Kosovo: juichen voor de Zwitsers.

Nicolasen, L. (2014, may 12). Hoe de winst van Conchita Wurst een doorbraak voor de transgender werd.

NOS. (2018, june 26). Albanezen willen FIFA-boete Zwitsers duo betalen.

Stephens, H. (2016, may 15). Eurovision 2016: Ukraine’s Jamala wins with politically charged 1944.

Trouw. (2008, august 9). Oorlog tussen Georgië en Rusland.

Vuletic, D. (2007). The socialist star. Yugoslavia, Cold War politics and the Eurovision Song Contest. In Raykoff, I, & Tobin, R., (Eds.), A song for Europe: popular music and politics in the Eurovision song contest (pp. 83-98). Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.