The design of breaking news on the Hong Kong protests

September 17th marked the 100th day of ongoing protests in Hong Kong and news platforms such as the BBC brought—yet again—large amounts of attention to the complicated issue by releasing videos to give a recap of the current conflict. Starting from June 9th, the Hong Kong protests were not a flash in the pan: they have evolved and developed in both online and offline spaces.

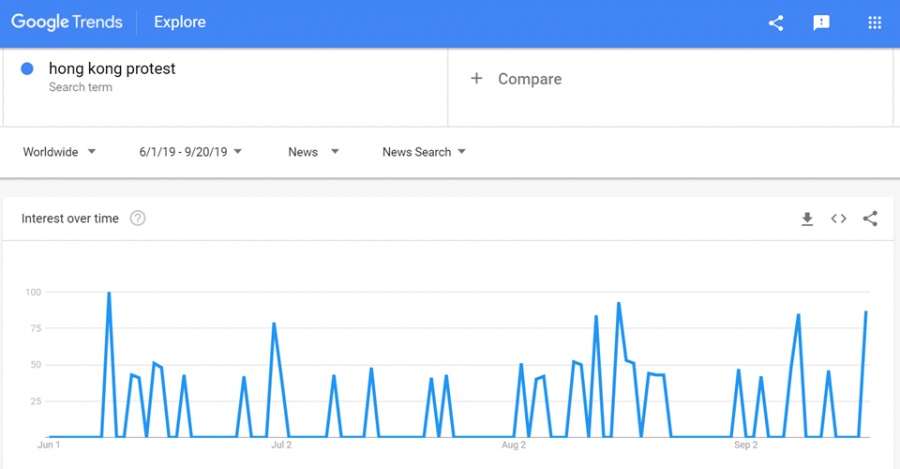

According to Google Trends, the number of HongKong-related items on news platforms has peaked repeatedly. Rather than being a piece of breaking news on the June 9th protest, this media coverage is more of an endless ‘issue attention cycle’ (Dawns, 1972) for keeping audiences updated. The non-stop media attention, in this case, raises several questions when examined as falling within the genre of 'Breaking News': How does it start? What do we 'witness'? And, more crucially, how do we see it?

Figure 1: Google Trends shows the number of coverages of Hong Kong Protests on news media during 100 days

In this article, we take breaking news to be a specifically designed genre of knowledge offered to audiences, and we will examine how mass media design the story of Hong Kong protests: how are the protests narrated, portrayed, motivated, and framed for audiences. For this study, data was collected from The New York Times, Fox News, CNN, BBC, The Guardian, and Al Jazeera.

100 days (and counting) of Hong Kong protests

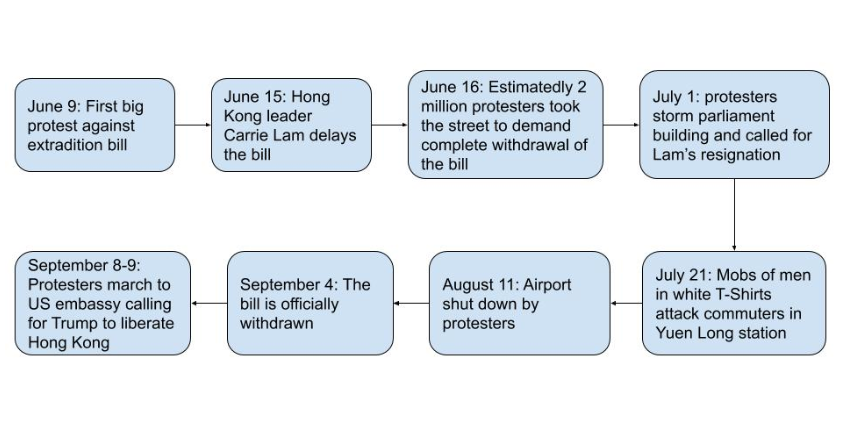

Before we start our analysis on how mass media design construct the breaking news stories of the Hong Kong protests, we will illustrate the storyline, starting from the 9th of June, by naming the ‘big moments’ that emerged in the past months.

Figure 2: Storyline of Hong Kong protests by naming the big moments

The starting point of Breaking News

When looking at the articles on the June 9 event in Hong Kong published by different news platforms, we can see that there are some similarities and differences in the way media outlets introduce their respective stories. Of course,he protests that happened on that day were not the first ones related to the extradition law. Fox News, for example, referred to the protest held by lawyers on June 6th and a march against the law on April 28th. However, the protests on the 9th of June gained greater attention from mass media due to the large number of people present at these protests. Platforms such as The Guardian, BBC, and Al Jazeera start their story by giving the reasons or triggers behind the protest: the proposed extradition law threatening judicial independence of Hong Kong, which is strongly resisted by protesters.

CNN’s starting point is to describe the scene of the protests and explain the historical relationship between Hong Kong and China, and then go into the details, such as the reason(s) for the protest and the actions performed by different actors. As for The New York Times, the article first mentions that the protests culminated after clashes with the police. The demonstrations were called 'a stunning display of rising fear and anger over the erosion of the civil liberties.'

Just like CNN, The New York Times also made connections to multiple older events such as a protest against the Chinese national anthem and the disappearance of a Chinese billionaire. Despite the continuation of protests (and, concomitantly, of news reports), there are some standard factors that characterize the big storylines, the moments of ‘Breaking News.’ Such factors are: violence between protesters and police resulting in casualties, statements from key political actors which could determine the course of events, and actions affecting bystanders such as the tourists at Hong Kong airport.

In the following sections, we will dig into the sources, actors, rumors, and frames with a thematic approach, in an attempt to unveil the big design of the breaking news on ‘Hong Kong protests.’

Building the fact: Multimodality and the hybrid media system

The concept of the eyewitness is in itself a powerful knowledge ideology in our media universe—'what we see' has the power to define what 'we know'. This is particularly applied to the news industry: 'I saw it happen, it was shocking.' In the case of the Hong Kong protests, primary sources as organized by media outlets illustrated how facts are knitted into a sort of map, renewing the logic of the eyewitness knowledge ideology in today’s online-offline nexus defined by multimodality and the hybrid media system.

Media editors compose sources functioning along different modes , such as text, images, and videos,to create meanings for audiences. The collection of these different modes or elements contributes to how audiences perceive the event or situation. In our case, we find that aerial photography, live reports with a correspondent reporter in the scene, interviews with different individuals, edited videos with captions, footage from media platforms, and unnamed eyewitnesses (see figure 3) are the main sources for the reports. Specifically, hyperlinks are presented to audiences for navigation and also as a form of clickbait leading to articles on the relevant context of Hong Kong protests, for example: 'Why are there protests in Hong Kong? All the context you need.'

This protest video came out on June 9th with the caption: 'Critics say the plan would erode the city’s judicial independence.' According to BBC’s article following this video, 'they were protesting against a controversial extradition bill that allows suspects to be sent to mainland China for trial. Organizers say there were one million people, which would make it the biggest march in more than 20 years. Police say there were 240,000 at its peak.' This video combined aerial images of the march with the sounds coming from the crowd, images of protest banners standing out, narratives of the correspondent report including interviews with four protesters (two speaking Cantonese, two speaking English), and the estimated numbers in the article. This all aimed to give audiences a clear impression on how massive the protest was, and also highlight the central topic of the protest.

In the breaking news of Hong Kong protests, mass media is not the only host. Sources from social media are intertwined with mass media, and both resonate through one another. Twitter users’ videos, official speech videos from the government leader, protesters’ monologues on why they stormed into parliament are edited and curated into news reports, but voiced by actors to protect protesters’ identity.

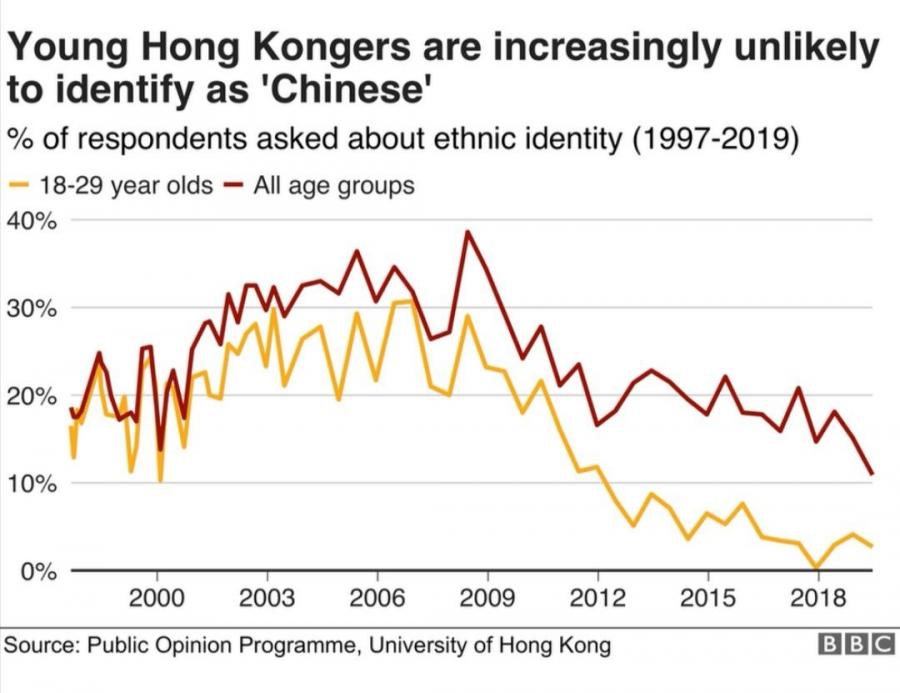

Data from the University of Hong Kong's Public Opinion Programme was also used to discuss the ethnic identity of Hong Kong's young citizens (see figure 3). All kinds of resources and information are intentionally organized to augment the factuality of the protest. What we can notice here is that the violence and scale of protests in Hong Kong are evidently highlighted, which makes them the focal point of news reports. From this point on, the design of narration starts emerging.

Figure 3: Data of young Hong Kongers’ enthic identity as Chinese from University of Hong Kong

Narrating the fact: characterization and dramatization

As pointed out before, the fact of the protests is actually the ‘highlighted fact’ which is selected and made salient by media. But what aspects are specifically highlighted in the story of Hong Kong protests? In our findings, the narration of this story extensively featured characterizations of selected actors and dramatization of the protests within aa bigger master narrative.

“In this ongoing battle, protesters are presented as the unified agents, the powerless empowered by themselves.”

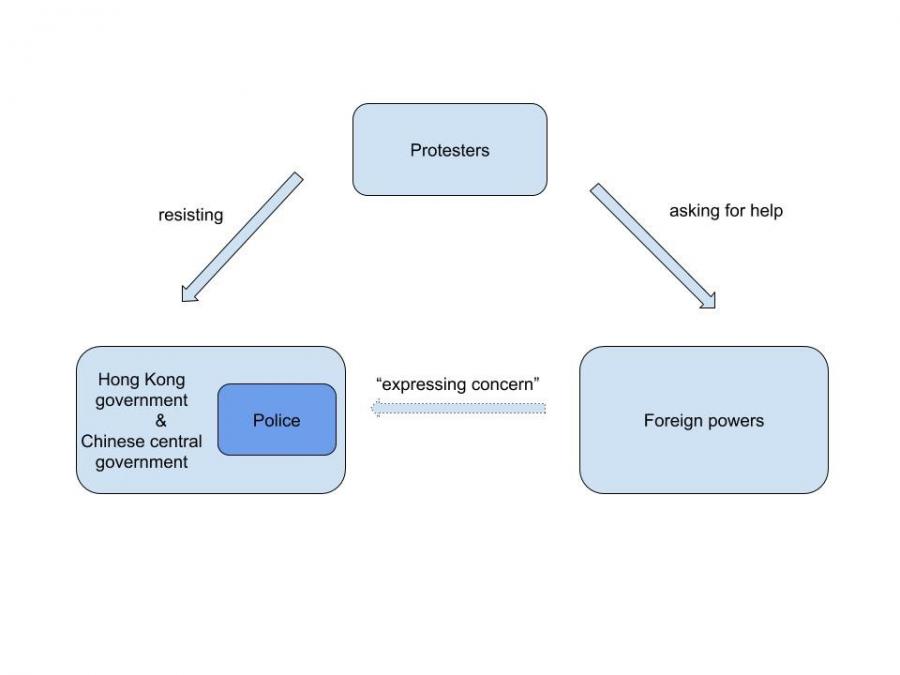

In this big story, actors are introduced and reintroduced to the stage every once in a while. However, some of them are always in the spotlight. These are protesters, police, the Hong Kong government and the Chinese Central Government (Beijing) as well as foreign powers. By highlighting and repeatedly referring to these main actors through a specific design, mass media platforms characterize them for audiences to perceive the story in a certain way.

Figure 4: Relationships among actors

In this ongoing battle, protesters are presented as the unified agents, the powerless empowered by themselves. Western mass media often describe them as victims, anti-governmental and pro-democracy demonstrators, while also showing sensational pictures of bloody injuries, and featuring protestants' monologues explaining why they stormed the parliament. By visualizing the images of protesters associated with militant violence and fierce chaos, a powerful image of unity against the government is presented.

Figure 5 : Protesters used yellow umbrellas to reflect the Umbrella Movement

In this big story, protesters are not fighting alone. By re-introducing the historic moment of Umbrella Movements and foregrounding theUmbrella Movement members as actors, the portrait of protesters is reinforced by the connotations of such precedents.

Figure 6: Police are using pepper spray

CNN News and The New York Times clarify the police's violence commenting that they 'have no choice but to use force.' With no denying that police takedown protesters, the police are characterized more as an innocent mediator between the protesters and the government. However, in The Guardian, BBC and Fox News reporage, the police and their supporters are labeled as violent and ruthless as they are depicted shouting into the camera, using rubber bullets and teargas. In the eyes of audiences, they are portrayed as a merciless tool for the Hong Kong government to implement the repression of the protest.

Carrie Lam, acting on behalf of the Hong Kong government, was seen as a ‘lame duck’ in both CNN and The Guardian, a derogatory nickname originally given to her by protest organizers. On the contrary, Fox News showed Lam’s sadness and struggles causing sympathy among readers, building up the image of a leader who would rather be more responsive to the public and keeps making promises about the future. With the exception of CNN News that employed a less hostile tone discussing the Chinese central government, other media outlets paint a portrait of China as a ‘liar’ who is going to withdraw the promise of Hong Kong’s democracy and deprive its people of their human rights.

Foreign powers including the U.S.A, the British government and the G20 summit were described as a ‘savior’ for Hong Kong in its current state. Protesters marched to the U.S. Consulate in Hong Kong to call for help from Trump and the G20 Osaka summit. Meanwhile, the British government also criticized human rights abuses. Thus, an image of heroic foreign powers was constructed through references to repeated support for human rights cases in Hong Kong.

Figure 7: Protesters marched to the U.S. Consulate for help

Dramatization: rumors and vague information

The protest story has evolved discursively. Rumors and innuendos based on vague materials regarding the actors are often presented to audiences for a dramatized effect, functioning like teasers for the audiences’ curiosity. Also, particularly in our case, this effect could reinforce the actors' constructed portraits with innuendos, and thus contribute to the big narrative.

With unclear and incomplete grass-roots video proof, people questioned the motivation of the attack launched by masked men in white T-shirts at the Yuen Long station on July 21st and 22nd. The assailants were suspected as triad members, and the act was said to be done by pro-Beijing officials, hiring thugs to intimidate protesters. However, this was vehemently denied by Lam later on.

Figure 8: Men in white launched an attack in Yuen Long station

On the 13th of August, a reporter from mainland China named Fu Guohao was pulled down and zip-tied by protesters at the airport, suspected as ‘a spy’ from mainland China on a special mission, but CNN later showed tweets proving that Fu had legally entered Hong Kong only for news reporting.

Figure 9: A netizen is declaring Fu’s real identity

Framing the Hong Kong protests: Causal diagnosis and moral judgment

In this section, we will examine how Hong Kong protests are framed through causal diagnosis and moral judgment, so as to show how mass media organize the audience’s experience of ‘fact.’

“This coverage presents the moral grounds for the protests and makes readers construct moral evaluations of both the protesters and the Hong Kong government.”

Similarly to the storylines and the portraits of actors discussed in the previous sections, frames emerged and changed episodically with new actors coming to the stage and bringing readers/audiences into new plot developments. However, are these really new plots? Let’s shed a little light on this drawing from frame analysis.

At the early stages of the story, titles and leadsof the news media, particularly those of The Guardian, BBC, and Al Jazeera, provided a logic of ‘why the protests happened’ with a clear accusation of the proposed extradition laws. Take The Guardian as an example. By stating that 'Critics say law will allow China to pursue political opponents and legitimize abductions', this coverage not only provides a legitimate reason for the protests without naming any 'critics,' but more importantly, it presents the moral grounds for the protests and makes readers construct moral evaluations of both the protesters and the Hong Kong government, who proposed the extradition law. As such, the event is politically defined and diagnosed.

Figure 10: The headline and lead of June 9th protest by The Guardian

The breaking news coverage of Hong Kong protests focuses not only on a substantial issue—the extradition law—but also on the non-stop battle between the empowered and the powerless: the repeating portraits of police and protesters. Take Fox News as an example, which seems to be presenting a back-and-forth of arguments between Lam and the protesters: after she makes announcements on her political position, the report usually follows up with the protesters’ reaction to that announcement—the battle between the powered and the powerless will not and cannot cease.

Figure 11: Video about Carrie Lam giving an official announcement

As we can see in the visual design of Hong Kong protests on multiple mass media platforms—Fox News, CNN, BBC, The Guardian, Fox News, and Al Jazeera—‘sensational scenes’ come into play. Here, sensational scenes refer to the specific scenes where readers/audiences are alarmed and emotionally provoked. Such scenes include pictures and footage of brutal clashes between police and protests, huge ‘seas of protests,’ and the stories told by ‘unnamed’ individuals. Like watching a melodrama, we news followers are brought into the specific time-space, or chronotope, where we perceive the news in the same way as drama audiences, being emotionally being affected by dramatic moments. By repeating the scenes of police violence and the of protests as victims, the ‘fact’ of Hong Kong protests is reinforced through moral evaluations towards the two main actors.

The design of the Hong Kong protests

The design of the Hong Kong protests is narrated as a ‘historical revolution empowered by the powerless agents fighting within the post-colonial context.’ In our findings, several crucial elements are found as key pieces for mapping the big narrative: multimodality, the hybrid media system, characterization, dramatization, causal diagnosis, and moral judgment.

We observed how mass media and social media resonate together with both visual and audio sources to build a factuality of the news. This factuality is sequentially narrated with a script that foregrounded several actors and kept our attention through discussing ambivalent ‘fact’: rumors, suspense, and vague materials.

In our study, the portrayed actors and dramatization are found to be instrumental for reporting on the ongoing protests, especially the characterization of different actors is part of the larger narrative . In the news industry, factuality is often selected and made salient or highlighted by the media (Sheeler & Anderson, 2013). Framing is something we all do in our communication and in this sense there is not something inherent 'wrong' in framing. Point is, that this editorial framing is a choice - and there can be good arguments to opt for that choice - that guides the evaluation of the news by readers and viewers. In our case, we see how mass media highlighted the aspects of a political cause and of victimhood in the story of the protests. By doing so, the audience’s ‘experience’ of the news in Hong Kong is ultimately ‘organized’ by the design of media. Being aware of those frames helps readers to - more critically - evaluate the news reporting in itself.

References

BBC News. (2019, September 17). Hong Kong: Looking back at 100 days of protests - BBC News [Video File].

Cheung, H., & Hughes, R. (2019, September 4). Why are there protests in Hong Kong? All the context you need. BBC News.

Chuen Ng, H. (2017, March 15). The Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong. Diggit Magazine.

Diggit Magazine, wiki: Chronotope. (n.d.).

Diggit Magazine: Wiki Frame. (n.d.).

Downs, A. (1972). Up and down with ecology: The issue attention cycle. The Public Interest, 28, 38–51.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press.

Hong Kong protesters demonstrate against extradition bill. (2019, June 9).

Procházka, O., & Blommaert, J. (2019) Ergoic framing in New Right online groups: Q, the MAGA kid, and the Deep State theory, Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies paper 224.

Ramzy, A. (2019, June 9). Hong Kong March: Vast Protest of Extradition Bill Shows Fear of Eroding Freedoms. The New York Times.

Sheeler, K. H., & Anderson, K. V. (2013). Woman president: Confronting postfeminist political culture (Vol. 22). Texas: A&M University Press.