How and why Wallonia and Brussels oppose the CETA Treaty

Reviewing some arguments from a David-Goliath debate

Upheaval in Europe: the Walloon and Brussels regional parliaments in Belgium have raised serious obstacles to the conclusion of a massive Free Trade Agreement with Canada called CETA. Given Belgium's rather complex constitutional make-up, the refusal of CETA by these regional parliaments means that Belgium, as an EU member state, cannot approve the agreement; and given the EU's rule of unanimity, this in turn means that the entire EU cannot legally conclude the CETA agreement with Canada. Obviously, this David versus Goliath battle has become international headline news over the past week.

David versus Goliath

The battle is waged in the Brussels negotiation rooms as well as in the mass media, and for obvious reasons, it has become quite heated in the Belgian media. Here are some arguments that were widely used over the past week, mainly by spokespersons for the (Flemish) business community and political world..

- Wallonia, which is ruled by a Social-Democratic/Christian-Democratic coalition, opposes CETA just to spite the Federal government, from which both parties were excluded. In Flanders, politicians add that Wallonia also wants to spite the Flemish region, which would benefit most from CETA. Opposition to CETA, in short, is merely an internal conflict in the complex Belgian state.

- The Walloons articulate petty interests, infinitely smaller (in fact, insignificant) when measured against the tremendous benefits that CETA will bring. The Walloons defend the interests of their small farming industry against the giant agro-industries of Canada. They do not understand how much CETA would bring to the economic development of their region.

- Wallonia makes Belgium look bad. Belgium has always been the EU's best pupil and hosts its institutions; being the only member state to block this enormous agreement causes dramatic reputational damage to the country.

The opposition of the Walloon and Brussels parliaments is not against "a free trade agreement"; it is against a particular concrete element of such treaties.

Most of these points are, no doubt, real. But they are peripheral in the range of arguments raised by the Walloon and Brussels parliaments. Walloon and Brussels, yes - narrowing the conflict to the Walloons bypasses the fact that two Belgian regions oppose CETA. The Brussels Region coalition, incidentally and uncomfortably, includes the Liberal parties, who are also in the Federal coalition - which instantly cripples the first of the arguments listed above.

Why?

The second argument is simply untrue. The opposition of the Walloon and Brussels parliaments is not against "a free trade agreement"; it is against a particular concrete element of such treaties. That element has in the meantime become infamous: the so-called "Investor-State Dispute Settlement" (ISDS) provision. This provision has been included in several large trade agreements (such as NAFTA) and, in its simplest formulation, grants private corporations the power to legally challenge national governments when legislation is judged (by the corporations) to damage real or expected profits - often cleverly called "indirect expropriation". Damage claims by corporations against national governments can reach hundreds of millions of Euros per case.

ISDS procedures are unilateral: corporations can prosecute states but states cannot prosecute corporations in the same way.

ISDS has a bad track record, for several reasons. One, it has been used by corporations to fight legislation which is grounded in pretty sound public interest concerns. Thus, reports Guy Standing in a recent book, the tobacco multinational Philip Morris attacked Australia's "plain packaging law" with a multimillion dollar damages claim because, obviously, it may dissuade people from smoking. While this claim was unsuccessful, the same corporation has filed ISDS complaints against numerous other governments. Similar cases have been filed by pharmaceutical companies against governments legally capping the cost of medicines, and, cynically, also against the government of Spain, in full economic crisis, for withdrawing subsidies for sustainable energy investments. Ecuador has to pay $1.8 billion to Occidental Petroleum for the (lawful) termination of an oil concession contract - a staggering 2% of the national GDP, according to Standing.

Second, ISDS procedures are unilateral: corporations can prosecute states but states cannot prosecute corporations in the same way. It is explicitly seen as an "investor protection" measure. Rulings are also ad-hoc, in the sense that the judges are not held to jurisprudence and precedent and can decide by majority vote - without access to appeal. Unsurprisingly the majority of cases brought forward were concluded in favor of the corporations.

ISDS-model procedures enable private multinational corporations to challenge and overrule democratically constituted regulations

Third, the procedure is terrifically expensive, and even if states win the case, they face millions of Euros in legal costs. Standing writes that the average trial cost is $8 million, with some trials costing as much as $30 million. Combined with the fear of astronomical damages, potentially affecting, as in the case of Ecuador, the macro-economic situation of the country, governments adopt a "prudent" attitude and prefer to avoid passing particular kinds of legislation - notably stricter social, public health and ecological rules - rather than to risk having to face an ISDS battle. Standing bitterly remarks that ISDS claims have become an industry in their own right, with large corporations and venture capital funds active in direct overseas investment increasingly viewing it as a new source of substantial income - which explains the rise in ISDS claims over the last handful of years.

Finally, however, there is a larger argument. ISDS-model procedures enable private multinational corporations to challenge and overrule democratically constituted regulations - a privilege not awarded to anyone else, and an acknowledgment of a new relationship between economy and democracy. Traditionally, economic actors need to comply, like anyone else, with the laws of the country where they deploy their activities. Under an ISDS system, this is no longer true: multimational business becomes a jurisdiction of its own, no longer entirely subject to democratically constituted legal arrangements to which their activities must be adjusted. Equality under the law is no longer the unshakable principle of the democratic rule of law, and the sovereignty of the polity - another cornerstone of modern democracy - has been substantially reduced.

What about democracy?

Tongue-in-cheek one can add that accepting ISDS seriously reduces the democratic choice of citizens. Whether one votes for left- or right-wing parties, for neoliberal or socialist and ecological political agendas: it doesn't really matter. Any government attempting to introduce policies perceived to run counter to the business strategies and profit expectations of multinational corporations will be welcomed by lawyers filing colossal ISDS claims anyway.

This is why the Walloon and Brussels parliaments oppose CETA. For, while chapter 8 of the treaty acknowledges some of ISDS's shortcomings and prefers the term "Investment Court System" (ICS), the ISDS template remains almost entirely intact - and the arguments against it as well.

Over the past day or so, the real issue - ICS - has finally emerged as a topic of debate in the Belgian mass media. Its defenders are playing it down: ICS is actually a mere detail, an "operationalization", a hardly relevant practical implementation of restricted scope, an innocuous gesture to reasssure investors, and so forth. Which begs the question: if ICS is that unimportant, why not remove it from the treaty then, knowing that this is the problem preventing its conclusion?

How?

Let us now turn to the third argument: the Walloons make Belgium look bad. Negotiating ISDS has taken seven years of hard diplomatic work, defenders argue, and such work should not be dismissed by the silly whims of some small political community.

For several years now, a major EU-wide campaign has been going on against large trade agreemens such as CETA

The ISDS agreement has indeed taken quite a bit of work to be drafted. But this work was done, mostly, in deep secrecy and by negotiators who did not feel constrained by the silly whims of some small political community. It was, like most of the EU's large legislative initiatives, the work of lobbyists. And in fair EU tradition, the treaty was offered for approval only when the texts were "final" - meaning that only small proviso- and exception statements could be added by national bodies, but that substantial re-negotiation is out of the question. Which is why the EU took the questionable step to issue a real ultimatum to the Walloon and Brussels governments: a firm yes or (strongly dispreferred) no had to be given before the end of the EU Council meeting in Brussels on October 21. Tremendous pressure was put by the entire EU-top on the Walloon Minister-President, quite reminiscent of the way Greek PM Tsipras was treated during the Greek debt crisis in 2015.

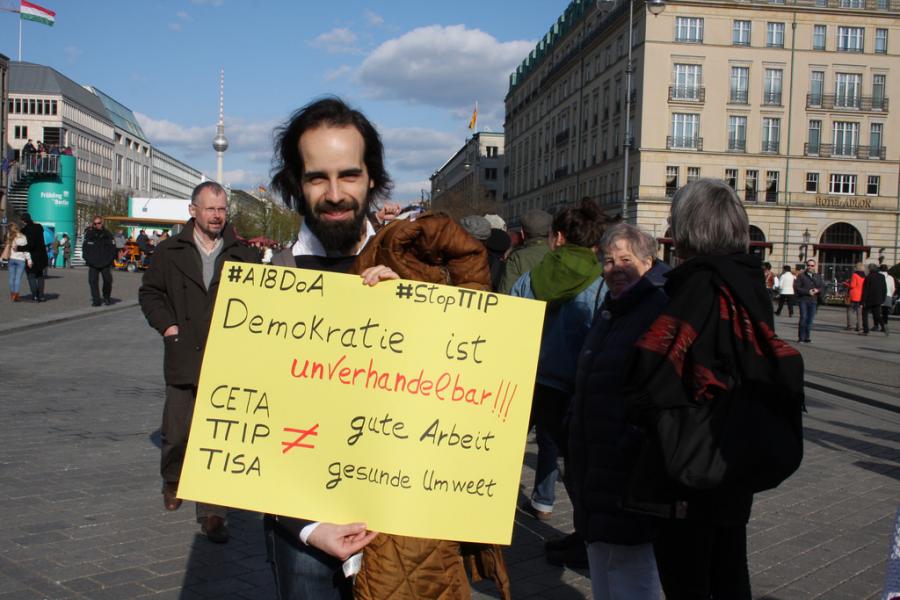

To be sure, the Walloon and Brussels governments are not alone in their resistance to ICS and other ISDS-type mechanisms. They may be the only governments raising objections, but for several years now, a major EU-wide campaign has been going on against large trade agreemens such as CETA and, even more intensely, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with the US, which also contains an elaborate ISDS procedure.

Civil society organizations advocating environmental, sustainable economy and social economy policies have constantly provided detailed and critical information and analyses of the negotiation documents that were available. Millions of EU citizens have signed petitions and marched in protest against the structure of such treates as well as the lack of transparency by means of which they were drafted and concluded. And in several EU- member state parliaments as well as the European Parliament serious concerns were raised. They have been overruled.

Cornelia Reetz, Stop TTIP

The Walloon and Brussels parliaments employ what cannot possibly be presented as an "abnormal" method in voicing their objections: they proceed along the only legally binding route available in EU-decision making: that of subsidiarity. The EU needs the consent of its member states and respects their internal structures of decision-making. As I explained at the outset, that means, in practice, that the Belgian government needs the approval of all of its subordinate governments - an effect of the never-ending reorganization of state power in Belgium over the past decades. And this is the only legally valid democratic procedure by means of which the EU can conclude the CETA agreement.

The Walloons did not offer their reservations in a "whim", and neither in a knee-jerk reflex of resistance against the Belgian federal coalition. Their objections were voiced long ago, and repeated over and over again, but no satisfactory response was forthcoming. Since their consent is not a matter of choice but one of necessity, the defenders of CETA could have had some more respect for the - ultimately quite powerful - democratic institutions, and negotiated with them long prior to the self-imposed deadline that now triggers a huge crisis.

The EU has a huge problem, and even its leading functionaries are sharply aware of it

Tremendous amounts of scorn have, in the past, been poured onto populations who rejected EU proposals by means of referendum - one can check the Brexit file on Diggitmagazine.com for evidence, and return to the Greek "no" of 2015 for further support. Referendum voters were misinformed and ingnorant of the real issues, they could not understand the complexity of the topics they had to vote on, and were generously helped in this by malicious and dishonest populist politicians, it was said (begging the question as to why such flaws would be asbent from regular election campaigns?) The results of referendum votes, many of which have only advisory powers, have, consequently, been dismissed, overruled, or converted into minuscule adjustments of the original plans.

The Walloon and Brussels parliaments have not opted for this controversial and too-often discredited tool, and just use "ordinary" political-professional work: parliamentary debate, resolutions, vote - decision, period. And the EU Treaties solemnly repeat, over and over again, that the Union shall be ruled not by force but by consent and respect for the democratic sovereignty of member states wherever it applies. So, perhaps this incident is highly unpleasant and exceptional. But that in itself is an indicator of a malaise, because the procedures used by the Wallon and Brussels parliaments are ... entirely and compellingly normal.

The EU and its problem

The EU has a huge problem, and even its leading functionaries are sharply aware of it. The malaise I hinted at is the highly questionable legitimacy of the "actually existing EU" - not the one so voluntaristically described in its treaties, but the one that does its daily business in Brussels. Especially in 2015, the EU's annus horribilis, issues of democratic legitimacy erupted all over the Union. In the Greek debt crisis, the EU showed a decidedly oppresive face, utterly destructive of, and even openly hostile to, democratic tradition. In the refugee crisis it showed a repressive side which was for many a violation of its most loudly proclaimed principles; and in the terrorism crisis it opted for the reduction of privacy and civil liberties - again violations of what it is supposed to stand for. Add to this the sustained emphasis on neoliberal austerity policies, and it is easy to see why the EU has ceased to be the inspiring project of peace, solidarity and prosperity it used to be for a generation of its citizens.

In fact - and elections and referenda increasingly demonstrate this - the EU now counts many millions of its citizens who are not against the Union per se, but reject the Union in its present state. Such people, thus, are not "Eurosceptical" in the sense of, e.g., Wilders and Farage, but Eurocritical. In the public debate (and the views of the EU-leadership) this crucial distinction is missed and Eurocritics are lumped together with Eurosceptics. While, to name just one, Jeremy Corbyn and his UK Labour Party demonstrated how hopelessly inadequate - and manipulative - it is to present people with a black-or-white option: either you endorse the EU as it is, or you get no EU at all. A similar simplism has been used in the CETA crisis now: either you approve the agreement as it is, or you get no agreement at all.

In any decent politics, a third choice should be available: "yes, but". Yes, we wish to maintain this system, but on the condition that changes, that it is profoundly, not cosmetically, improved. The Wallon and Brussels parliaments, just like several other parliaments and millions of citizens, have demanded precisely that. And if the EU does not understand how normal such a political demand is, it is unlikely to recover from its malaise. In fact, the malaise may prove to be a fatal disease.