The impact of Instagrammable Exhibitions

Dutch newspapers such as De Volkskrant, Het Parool and AD have recently reported on the growing popularity of ‘Instagrammable exhibitions’: pop-up exhibitions and museums such as the Museum of Ice Cream in New York and Wondr in Amsterdam that facilitate photography and selfie opportunities by fabricating themed decors, luminescent colours, and interactive props (Lauson, 2019). By doing so, these new enterprises engage with younger generations' need to share their experiences and photographs on social media, particularly Instagram.

While pop-up museums are called such merely ‘because that is what people understand’ and push the boundaries of what a museum really is, several of the more traditional art museums have also utilized this phenomena. They have started to create exhibitions with a focus on experience, interactivity, and the aesthetics of the artworks. With these exhibitions, which are easy to photograph and consist of art objects geared towards selfie-taking, art museums hope to attract social media users as a new type of public.

Instagrammable exhibitions in the Netherlands

Over the past few years, this trend has become visible in the Netherlands as well. For example, the Moco Museum in Amsterdam created a Roy Lichtenstein 3D installation room based on Lichtenstein’s painting Bedroom at Arles (1992) in 2017. Here, visitors were invited inside this immersive room to experience the artist’s painting from within.

Museums in the late 20th century set out to remake themselves as a more dialogic kind of institution

From March 2019 until August 2019, the Voorlinden museum exhibited one of Yayoi Kusama’s world-famous infinity mirror rooms, namely Gleaming Lights of the Souls (2009). By buying a ticket for a specific timeslot, visitors got to visit this room with a maximum of two people for exactly 45 seconds (perfectly timed by an employee holding a stopwatch), in order to accommodate the ultimate experience.

Figure 1. Taking a selfie in Kusama's Infinity Mirror Room at Museum Voorlinden, 2019

Further, the Tropenmuseum equipped their exhibition Cool Japan, displayed from September 2018 until September 2019, with the installation room Colorful Rebellion – Seventh Nightmare by Sebastian Masuda. The installation consisted of a colourful room with a white bed, revealing the complex imaginary world of the artist whilst also being a portrait of the Harajuku neighbourhood in Tokyo. However the room was mostly promoted as the perfect Instagram and selfie spot.

A new form of Participatory Art

The creation of these Instagrammable art exhibitions by the Moco Museum, Museum Voorlinden and the Tropenmuseum can be considered a new form of participatory art, as described by art critic Claire Bishop. She explains participatory art as a form of art that directly engages the audience in the creative process so that they become participants in the event. Here, the act of photographing the artwork and sharing the image online makes visitors co-producers and collaborators in the the artwork.

While audience participation has now become a familiar and established aspect of aesthetic practice in the contemporary art world, it is a concept which only emerged in the 1900s. Claire Bishop explains that Italian Futurism, Russian Proletkult Theatre and Paris Dada were three crucial moments in art history that contextualise this social turn in contemporary art (Bishop, 2012, p. 3).

A short history of Participatory Art

Artistic interest in and collaboration with audiences grew during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Early audience participation pieces included Cut Piece (1964) by Yoko Ono, wherein the artist sat on a stage in a suit that audience members could cut with scissors as they wished, and 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (1959) by Allan Kaprow, which was one of the first ‘happenings'.

The rise of installation art also began in the 1960s, thereby expandingthe idea of spectator participation. Through installations the audience does not engage with the artist him- or herself, but rather with the installations they create. These artworks, which often occupy an entire room or gallery space, are created in such a way that the visitor has to walk through or around the installation to fully immerse themselves in the art. Take for example the work Raemar (1969) by artist James Turrell, who combined "architecture, sculpture, light and space to completely envelope the viewer in a coloured atmosphere." Yayoi Kusama even created her very first Infinity Mirror Room back in 1965, in which she placed hundreds of soft, phallic forms in a mirrored room.

From the 1980s on, contemporary and participatory art became central to museum activities and institutions started to embrace and acquire installations as both a historical and contemporary phenomenon (van Saaze, 2013, p. 19).

Changing the meaning of the museum

From the 1990s, heated discussions arose in art museums around 1) the relationship between artwork and audience, 2) the communication between museum and visitor and 3) the development of multimedia, eventually leading to a change in the meaning of museums (Kraemer, 2018, p. 82). While classical museums relied on the aesthetic value or luxurious nature of objects to supplement interest in the knowledge they conveyed, museums in the late 20th century set out to remake themselves as a more dialogic kind of institution, foregrounding the visitor's perspective and experience.

The audience is re-positioned as a co-producer of the artwork

Museums became aware of the disconnect between their own intentions and visitor perceptions, which initiated a shift in focus from the descriptive to the communicative (Hein, 2006, pp. 4-9). Museums started to use technologies such as mobile applications and guidebooks as a new form of communicating with and educating visitors. In concert with new media, a shared desire to overturn the traditional relationship between the artist, the art object, and the audience arose. Artwork became an on-going project whereby the audience was re-positioned as a co-producer of the artwork, rather than a mere visitor or beholder (Bishop, 2012, p. 2).

Through these developments, we can see a shift in focus from the object to the subject. Whereas participatory art invites the viewer to participate in creation, works like Kusama's Obliteration Room (2002) or Eliasson's Your Uncertain Shadow (2010) allow people to see themselves physically in the work. In these art forms, the focus is no longer on the artwork itself but on the visitor and his or her experience. This shift moves the focus from the object or installation itself towards subjects and enabling their experiences in art activities.

Merging participation and spectacle

Bishop (2012) explains that this new form of participation has merged with spectacle, initiating the creation of immersive experiences for museum visitors. A clear example in which participation and spectacle go hand in hand is Rain Room (2012), which was first exhibited at the Barbican Curve Gallery in London. Created by the young experimental group Random International, it invites the visitor to enter a hundred-square-meter downpour without getting wet (Wainwright, 2012). The group used new technologies to create a participatory art piece and were interested in how audiences would react. The work places the subject prior to the artwork itself, or as Florian Ortkrass, co-founder of the group, explains: ‘It does not make sense without anyone there’.

People were amazed by the experience the group had created, calling it ‘a loss of control’, ‘a deliverance of technology’ and ‘as close as we can come to being a God’. Visitors started to document their experiences and share them online. Due to the reach of these online posts, the Rain Room received a huge amount of popularity and fame, resulting in people queuing outside the exhibit for over twelve hours. In five months, more than 77.000 people had entered the room. At that point, Rain Room was the most popular attraction in Barbican history (Jury et al, 2013).

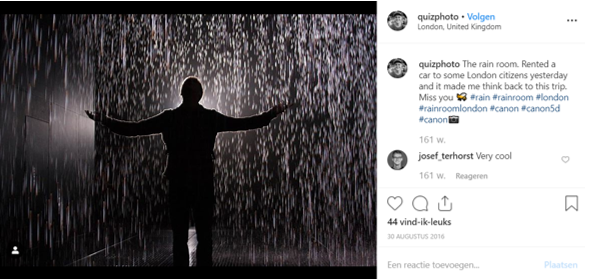

Jennifer Barnes, senior project commissioner and producer at Random International, noted how people use and reproduce an artwork through Instagram, explaining how ironic it is that ‘the group has been working on a 3D installation for four years, and that the first thing that visitors do is take a 2D image’. The #rainroom tag on Instagram has more than 62.000 pictures (e.g., Figure 1), not including images posted under more specific hashtags, such as #rainroomshanghai and #rainroommelbourne.

Figure 2. Example of an Instagram-post made in the Rain Room in London, posted by user @quizphoto. Screenshot taken on 2 October 2019.

Sharing is (not) caring

Another instance in which curators and artists discovered the public's desire to share their museum experiences online was James Turrell's Aten Reign (2013), exhibited at the Guggenheim in New York between June and September 2013. Turrell radically transformed the museum's rotunda into a luminous and immersive experience. The installation surrounded a core of daylight with five elliptical rings of shifting, coloured lights, filling up the whole room. The piece intentionally hides its technical workings from the visitor and therefore encourages people to form their own interpretation of what they see.

For this particular artwork, Turrell requested that visitors not take photographs because he found that documenting the artwork interfered with the experience. Nonetheless, over five thousand pictures were shared on social media platforms and especially Instagram (Figure 3). Visitors' desire to document their experience with the artwork was thus prioritized over the experience itself. Aten Reign showcases how visual aspects of an artwork, such as colourful lightning, can perform well on social media and therefore lure people into taking pictures. Here, the aesthetic power seems to decides what people wish to photograph and what not to (Budge, 2017, p.79).

Figure 3. Example of an Instagram-post made with Aten Reign in the Guggenheim Museum, posted by @levi_higgis. Screenshot taken on 2 October 2019.

The post-modernization of museums

Seeing the (perhaps unintentional) online success of artworks as Rain Room and Aten Reign, museums all over the world have begun to create experience-oriented exhibitions, responding to visitors' desire for immersive experiences. The post-modernization of the museum is initiated by using new technology and media to interact with and meet the needs of diverse audiences (Pardes, 2017).

In the postmodern museum, the exhibition has become a discursive space, wherein the art institutions are expected to offer opportunities for experimentation and critical reflection through immersive experiences (Pardes, 2017). This move represents a reconceptualization of the ‘white cube’. The idea of the white cube, which was the normative form of display for museums for most of the twentieth century, was initially created to focus attention on the individual work of art. With emphasis now on the visitor ('s experience), rather than the artwork, artists, curators, critics and gallerists have been active and enthusiastic collaborators in the process of reconfiguring the art of experience.

Art institutions are expected to offer opportunities for experimentation and critical reflection through immersive experiences

Further, art institutions have started to respond to the public's desire to document and share experiences online by creating so-called Instagrammable exhibitions. These exhibitions not only prioritize role of the visitor, but also encourage him or her to document and share their experience online, indirectly bringing new visitors to the museum. Museums serve today’s popular act of selfie-taking by promoting these exhibitions as fun and colourful backgrounds for visitors' images. By providing interactive props, photo-ops, and aesthetic backgrounds, and allowing visitors to move more freely through the space, museums lure in a broader audience via social media, especially younger generations that would not otherwise visit.

In these Instagram-worthy exhibitions, visitors are expected to navigate between different kinds of information and modes of representation (Henning, 2005, p. 145). An example of this is the introduction of interactive props to encourage participation. Through these props, museums signal to visitors that they no longer need to be quiet spectators following a linear display. Visitors are encouraged to talk to other people, make noise, and walk back and forth through an exhibition (Leahy, 2005, p. 115). Visitors are given the ability to choose their own path through the museum and therefore re-curate a museum visit based on what they wish to share online.

The mediatisation of art museums

Art museums have allowed social media, the internet and new technologies into their insitutions in order to create new interactive forms of education. In her book Museums, Media and Cultural Theory (2005), Michelle Henning even argues that with these adjustments, museums are becoming more like media.

The museum becomes a performance space, wherein the focus lies on the story of the visitor

Henning explains that with the creation of the experience-oriented exhibitions, museums are becoming story-centred, just like media texts (Weilenmann et al, 2013, p. 1844). The object is used to produce the subject through interactive techniques. The intention is to turn unfocussed visitor-consumers into interested, engaged, and informed citizens by focusing on interactivity and experience. By doing so, an attempt is made to make exhibits more relevant to people’s everyday lives (Weilenmann et al, 2013, p. 1844).

Steyn (2014) further argues that this current fixation on experience in art exhibitions erodes the differences between art and life, between the subject of experiences and its objects (p. 234). Through the use of Instagram, these exhibitions similarly erode differences between the online and offline. By displaying mediatic characteristics and entering the online world, the museum becomes part of the online-offline nexus.

This has changed how the museum is curated in the 21st century: the subject and his or her experience are now prioritized over the viewing of artwork. The museum space therefore becomes primarily a performance space (Greenberg, 2005, p. 228). In this space, the focus lies on the visitor's stories and narratives, making the experience more democratic, authentic and subjective (Steyn, 2014, p. 230).

Privileging the experience

However, critics such as Hilde Hein and Eilean Greenhill-Hooper argue that these exhibitions privilege experience over knowledge (Steyn, 2014, p. 230). This new emphasis on experience is, according to them, linked to the commodification of experience and the emergence of the experience economy (Henning, 2005, p. 93).

The mediatisation of the museum thus responds to this economy, being ‘a marketing strategy that seeks to replace goods and services with scripted and staged personal experiences to engage the participant in a personal way’ (Steyn, 2014, p. 230). Steyn argues that participatory art forms risk being absorbed by commodification, since both artists and curators constantly compete to stretch the limits of audience inclusion.

With the focus on Instagram-worthy exhibitions pushing aesthetics as well, this new phenomenon takes this idea even one step further, whereby art placed in the background of Instagram posts is used as a wallpaper or prop to create both an online memory and evidence that you have been there. Given the competition among contemporary artists and curators to stretch the visitor’s experience and use of art as a stage for selfies, the art experience becomes a form of entertainment and a commodity for sale.

When this happens, the difference between art and entertainment, in which art does not sell commodified experiences and entertainment does, might get lost (Steyn, 2014, p. 231).

References

Lauson, C. (21 July 2019). When art becomes a hashtag, do museums lose their meaning? The Globe and Mail.

Bishop, C. (2012). Artificial Hells: Participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. Verso Books.

Budge, K. (2017). Objects in focus: Museum visitors and instagram. The Museum Journal, 60(1), 57-85.

Greenberg, S. (2005). The vital museum. In S. Macleod (Ed.), Reshaping Museum Space (pp. 226-237). Routledge.

Hein, H. (2006) Public art: Thinking museums differently. AltaMira Press.

Henning, M. (2005) Museums, Media and Cultural Theory. Open University Press.

Jury, L. & Martin, E. (4 March 2013). The Rain Room in Barbican’s Curve Gallery draws 12-hour queues. The Evening Standard.

Kraemer, H. (2018). Media are, first of all, for fun: The future of media determines the future of museums. In G. Bast, E. Carayannis & D. Campbell (Eds.), The Future of Museums (pp. 81-100). Springer.

Pardes, A. (27 September 2017). Selfie Factories: The Rise of the Made-for-Instagram Museum. Wired.

Steyn, J. (2014). The art of experience in the age of a service ceonomy. In K. Brown (Ed.), Interactive contemporary art: Participation in practice (pp. 221-238). I.B. Tauris & Co.

van Saaze, van, V. (2013). Installation aArt and the mMuseum: Presentation and cConservation of cChanging aArtworks. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Weilenmann, A., Hillman, T. & Jungselius, B. (2013). Instagram at the museum: communicating the museum experience through social photo sharing. CHI, 1843-1852.

Wainwright, O. (3 October 2012). Random International installs torrential rain in Barbican gallery. The Guardian.