Migration, the common thread through my existence

By means of this article I would like to take you on a journey through several layers of migration in the context of how globalization affected my personal experience. Layers of migration can be by force or by choice. Factors that may force migration may be health, wealth, and safety. This type of migration is often caused by one or more of the following global socio-economic changes: worldwide economic crises, worldwide pollution, wars etc. In contrast to the above, migration may also result from the choice to, for exampe, become an expat or to gain knowledge, e.g. as an Erasmus exchange student.

A refugee's journey

When I was five years old, my family and I fled from Surinam to become asylum seekers in the Netherlands. We were in search of safety because of the war that was raging in the interior. This war started approximately ten years after the first migration movement that was caused by the de-colonization process between the Netherlands and Surinam. The government of Surinam was overthrown in a military coup in 1986, which at a later stage escalated into war, for various reasons. The war was between the military force that instigated the coup and a guerilla group named the “jungle commandos” and lasted till 1992. This war caused the second wave of migration to the Netherlands. A significant percentage of the people that fled were people who originated from the interior, like my family and me.

Our journey as refugees was made possible through our connections, availability of transport costs, the type of traveling papers we possessed, and the threats we were able to avoid on our route.

My family was living in the capital Paramaribo when the war broke out, but because of military harassment and the fear of escalation, we left the city. Our intent was to flee to the Netherlands, but this could not be achieved through the conventional route from the Surinamese national airport, as it was in hands of the military. Instead, we took a route through the interior that would take us to the neighbouring country of French Guyana and from there we would fly to the Netherlands. A journey that normally takes a mere three hours by car and boat, took us two days of travelling.

I will give an impression of our trajectory and why it took two days. We went by bus from Paramaribo to Moengo using the regular infrastructure. Moengo was at the border of the area where the fighting was going on. Since the bus driver did not feel safe enough to proceed we were ordered off the bus. From Moengo we had to walk several kilometers by foot through the dense Amazon jungle in order to avoid the patrolling military. At an open space we encountered the jungle commandos who recognized us as family. They had a pick-up truck and offered us a ride for a part of our journey, after stating clearly though that they could not guarantee our safety. At a certain point we had to climb out of the pickup to hide in the jungle because there were military helicopters overhead. Night falls really early in the jungle and in the dark you cannot see where you are going, so we had to spend the night at a camp. Campfires for cooking or warmth were forbidden, as the smoke of the fire would indicate our position and could jeopardize our lives.

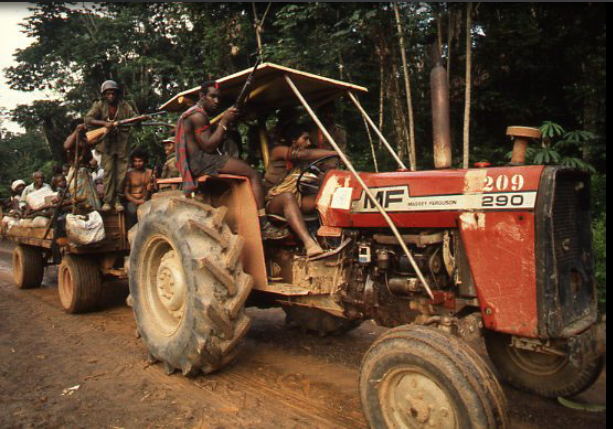

The next morning a tractor with a trailer, simular to the one on the picture above, helped us to continue our journey to nearby Boni Creek, for 30 Surinamese guilders per person. After the drive we had to walk the last kilometers to the creek in order not to make noise that could betray us. Finally at the Boni Creek, everything that you carried with you had to be left behind to create space so that as many people as possible could enter the boat. The boat had an outboard motor but the boatsmen peddled the boat out into the creek in order not to be discovered. Once out of the creek on the open Marowijne River they could use the outboard motor to proceed to Saint Laurent-du-Maroni. There we were picked up by French soldiers who took down our personal details and gave us a card that we could use at a refugee camp named Cawanee, where we resided for several weeks.

The camp was badly organized, so my mother’s sister who lived in Saint Laurent-du-Maroni took us in at her house until we received a laissez-passer. The above image shows what a laissez-passer document looks like. It is a legal temporary French document that gives you official permission to stay in the country for ten years. Because of our lack of knowledge of French, my mother's sister had to help complete the documents and communicate to civil servants in order for us to receive the documents. My father had quite some connections. One of them was the founder of a foundation in the Netherlands named WST (Welzijnsstichting voor Surinamers Tilburg). With the laissez passer and the help of my father’s connections we could travel to the Netherlands by airplane, paid for by WST.

The voice of migration: language and communication

Looking at the historical context the Netherlands seemed a logical choice of country to flee to. In the Dutch language Surinam and the Netherlands had at least one common cultural aspect. When we arrived in the Netherlands, however, we discovered that this common cultural aspect posed a problem for us. Surinam is a superdiverse country (Vertovec, 2007) with a rich migration history and because of this people are raised as multilinguals. Most people speak at least two different languages. The first language is mostly the mother tongue, e.g. people of African descent would speak one of various languages or dialects such as Auccaans, Saramacaans, Sranang Tongo etc., while people of Indian descent have Sarnami as their mother tongue, people of Indonesia descent Javanese, people of China descent Chinese, people of Dutch descent Dutch, etc. The native Indian people would speak their respective Indian languages. For most people the second language is Sranang Tongo and/or Dutch. Dutch is mostly used in Surinam in governmental and administrative and bureaucratic services, and in schools and offices, and commonly by people who have some level of education (Kroon & Yagmur, 2012). Our mother tongue is Auccaans which we spoke most of the time, followed by Sranang Tongo and/or Dutch. Dutch is commonly taught from elementary school on. But when we left Surinam I did not yet have a proper command of Dutch because I started going to school just before we left. Also, my parents would normally speak Auccaans to us children more often than Dutch, my mother more so than my father.

The different semantics of the lexicon of Dutch spoken in the Netherlands and Surinam sometimes created miscommunications for us.

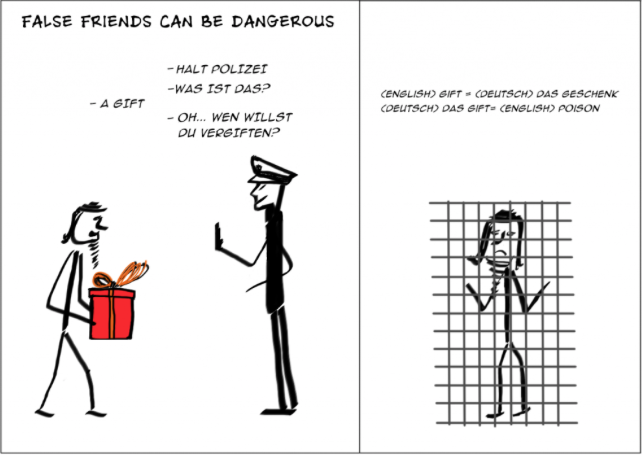

When I started learning Dutch I discovered that the "standard" Dutch lexicon and the Surinam Dutch lexicon contain words that are false friends, causing linguistic confusion. This means that a word can be written exactly the same in two different languages but have totally different meanings in them, as in the image above with the words Gift (poison) in German and gift (a present) in English. An example that I can recall concerns the word "bloot". In standard Dutch, the word means 'naked', but in Surinam it is used for being completely broke. My mother used it at home once and because of my knowledge of standard Dutch I could place her sentence "Ik ben bloot" (I am broke) in a Surinamese Dutch as well as in a standard Dutch context. This was a revealing discovery for me, because yes, she was broke but she was not naked since she had clothes on. A native Dutch person hearing this sentence would think that it is a language error, but in actual fact it is proper Surinamese Dutch.

In the beginning I used all my languages, and often literally translated my sentences from Auccaans to standard Dutch. I used whatever linguistic features I had at my disposal in order to make myself understood, also in the wrong context. In the image above the title of the book by the Surinamese author Edgar Cairo says "Ik ga dood om jullie hoofd" (I will die because of your head.) This is a literal translation from Sranang Tongo to Standard Dutch (Blommaert, Rampton & Spotti, 2011). These were the type of mistakes I made.

The teacher explained my problem to my parents, and consequently it became prohibited for me and my siblings to speak Auccaans at home in order to improve our Dutch. This solution, however, created another problem, as my command of Auccaans started deteriorating, and this made communication with family members that spoke only Auccaans a challenge. I understood quite fine what they where telling me in Auccaans, but was too shy to reply back in Auccaans because I was afraid to make mistakes and of being laughed at.

I discovered there were cultural linguistic differences too, as Dutch native children used jij and jou (both meaning you) when they spoke to persons who were not their peers. This was confusing and disturbing to me, because in the Surinamese linguistic culture politeness is taken really serious (Blommaert, 2010). A Surinamese child for example addressess non-peers formally, with their proper terms of address sir, madame, aunt, uncle, grand mother, grand father etc. Another example is that when grown ups are having a conversation, it is impolite for a child to interrupt. My impression was that native Dutch children did not have these rules at all. I knew all the Surinamese rules and was comfortable with them. It did happen at times though that I accidently used the Dutch rules at home and then I would get a lecture or even punishment.

Using tape recordings was a new form of communication technology to us.

Those days, long-distance communication and maintaining trans-local ties in the diaspora was made possible through the landline, tape recordings and hand written letters (Vertovec, 2007). Having a commodity like a fixed phone in your home was a normal thing in a modern country like the Netherlands. Surinam, even though it had been a Dutch colony, did not modernize at the same pace. A majority of the population did not have electricity, especially not in the interior, let alone a telephone. Maintaining communication with Surinam was, therefore, a serious endeavor.

Phone calls from the Netherlands to Surinam were expensive and normally used for short urgent calls only. Family members would even call collect, meaning that the receiver pays for the call. Strikingly the calls from the Netherlands to French Guyana were somewhat cheaper, as you can see from the above image. For French Guyana, even though it is in South-America, the phone tarifs fell under the European ones. French Guyana is still a colony of France so calling to French Guyana is still like calling to France. This shows that "distribution of such infrastructures is not necessarily democratically organized, and peripheral areas can be characterized by partial access to specific infrastructures for globalization" (Wang et al., 2013, p7).

To solve this communication problem my family would send tape recordings back “home”, in which everyone could have their say. On tape recordings sent to us from Surinam you would sometimes hear multiple family members giving messages that had to be distributed to other family members in the Netherlands. Tapes were sometimes also recycled in order to economize, leading to "mixed messages".

Staying for economic reasons

We arrived in the Netherlands without a clue of what would come next and how long we would be able to stay. We lived at the WST and also at an aunt's place for about three months before we received housing from the Dutch government. This was a fully furnished three bedroom flat. After months of living with relatives and people we didn't know it was a luxury to have a place of our own again. In that short period of three months our status changed from asylum seekers to status holders because the Dutch government granted us a residence permit for five years. The Dutch government stimulates status holders to start building up a normal life within their new society as soon as they have this status. This is also the reason why we received the flat so fast (The Hague municipality, Status holders in the Hague, 2017).

In a sense we had become economic migrants.

After almost ten years we became full citizens of the Netherlands and were granted Dutch citizenship. We were no longer asylum seekers nor status holders, but in everyday Dutch language we were still migrants. In effect we could have returned to Surinam after the war ended in 1992. However, we did not, because the war had disrupted and stagnated the economy. Now our goals had changed and we were in pursuit of another foundation, economic stability (Vertovec, 2007). If we would have migrated back we would have to start building everything up from scratch and we did not have the financial means to do that. This is one of the reasons that migrants often do not return to their birth country.

Migration in the knowledge era

I have been enjoying my safe foundation in the Netherlands for 31 years now thanks to the migration decision my parents made. Despite this safety, at the age of 25 I came to the realization that I wanted more out of life. I therefore decided to start the study International Business and Languages.

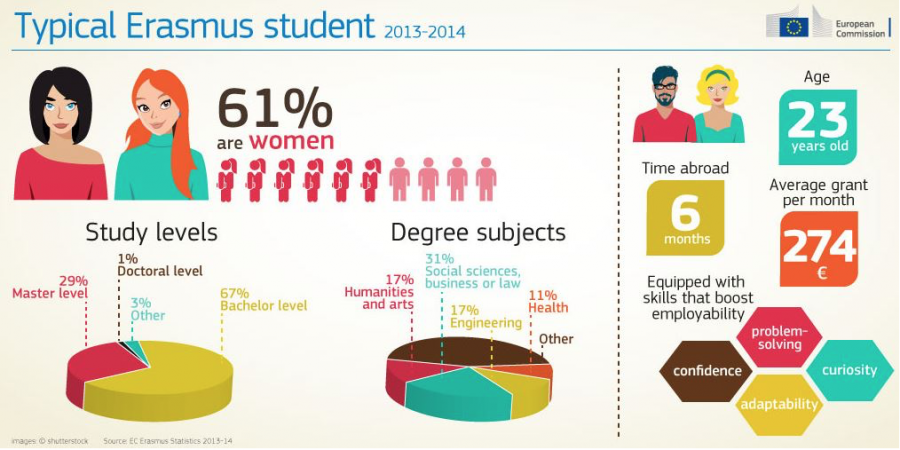

This program gave me the opportunity to become an Erasmus exchange student and to travel to another country to study at a partner university and meet all types of interesting people from all over the world. Becoming an Erasmus student was only possible because of the fact that I had the right traveling document, a Dutch pasport. It gives me the freedom to cross borders freely within the European Union, simply because the Netherlands is part of this Union. I did not need visas or permits, despite being a foreign national (Vertovec, 2007).

Communication via tape recordings and letters has been replaced by emails and blogs since the arrival of internet.

This time I was a migrant by choice, a knowledge migrant to be precise. Everything was arranged before I left. I knew where I was going and for how long, so there was no feeling of uncertainty. This migration was in a new era, with new means of long distance communication. I had a mobile phone at my disposal and one of the latest model laptops available.

I even became a prosumer because of the availability of the internet, my laptop and a website named “waarbenjij.nu” (whereareyou.now). I was now able to write blogs, as you can see in the above image, about my experiences and reach a broad range of family and friends who wished to be kept up to date about my adventures. At the same time I would also enjoy the blogs of other students and read about their adventures.

All of these things sound new and different but there is one phenomenon that I discovered that was the same as when we migrated the first time, and it's the experience of languaging. The main language that we had to speak during lectures was English. I soon discovered though that I had fellow students that would use for example Spanglish, a combination of Spanish and English, during conversations and presentations to make themselves understood. This made me think again of when I just started living in the Netherlands and the struggle I had with learning the language.

Conclusion

My family and I are by no means an exception when it comes to migration. People have been migrating to other cities and countries for centuries. However, the characteristics of modern globalization affect the experience. A person can go through several layers of migration, whether by force or by choice, in a short period because of the turbulent era that we are living in. It was a striking discovery for me that language plays such an important part in the migration experience, no matter where you go and how you arrive at the location where you want to be. I learned that trying to ignore one language in order to get a better command of the other may solve one problem but at the same time cause a new one, as your command of your mother tongue detoriates. I now know that having the correct traveling papers and connections opens borders for you. Also, the speed with which innovative tools for communication develop gives us greater possibilities than before to keep in contact with others throughout the diaspora at every step of the road.

References

Blommaert J., (2010). The sociolinguistics of globalization. Cambidge: Cambridge University Press.

Blommaert J., Rampton B., & Spotti M., (2011). Language and Superdiversity. Diversities 13(2).

Kroon S., & Yagmur K., (2012). Meertaligheid in het onderwijs in Suriname. Een onderzoek naar praktijken, ervaringen en opvattingen van leerlingen en leerkrachten als basis voor de ontwikkeling van een taalbeleid voor het onderwijs in Suriname. Den Haag: Nederlandse Taalunie.

Status holders in the Hague, 2017

Vertovec S., (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(6), 1024-1054, DOI: 10.1080/01419870701599465

Wang X. et al., (2013). Globalization in the margins: towards a re-evaluation of language and mobility. Applied Linguistici Review 5(1), 23-44..