‘My friends, I’m asking you...’: The Role of Newsletters in Bernie Sanders’ Campaign

Bernie Sanders is a well-known politician who ran for the U.S. Democratic Party nomination in the 2020 presidential elections. Newsletters were a foundational tool of Bernie Sanders’ campaign strategy. These newsletters are a key example of big organizing in Sanders’ campaign. This article analyzes the importance of these newsletters and the way they were utilized by Sanders' campaign team.

Bernie Sanders and Big Organizing

In their book Rules for Revolutionaries, Bond & Exley (who both worked for Bernie Sanders’ 2016 campaign team) define big organizing as “a way to understand mass revolutionary organizing that’s relevant today”, and as something that “leaders do in movements that mobilize millions of people" (2016, p. 1). Big organizing used to be the norm: from unions to new social movements, every transformational movement was powered by mass organizing. However, over the years, big organizing was displaced by small organizing, where an increasingly small number of mega-corporations hold power (Bond & Exley, 2016, p. 1). Small organizing is directly related to the professionalization of political consultancy (Lempert & Silverstein, 2012, p. 49).

In other words, whereas small organizing works from the top down, big organizing works from the bottom up. However, big organizing is now enabled by digitalization. Sanders’ campaign reintroduced big organizing by mobilizing millions of people to volunteer or donate money to support his campaign, mainly through newletters. People sign up for these newsletters on www.berniesanders.com “to tell Bernie [they're] in!”, sometimes after finding their way to the website through Facebook or Instagram advertisments. Sanders' advertisement library on Facebook shows a huge amount of advertisements, which are targeted to specific areas or states in the United States (Ad Library, n.d.).

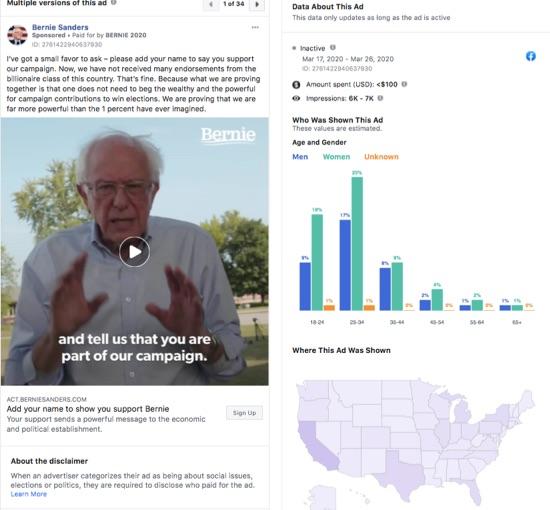

Above is an example advertisement from Facebook, where Sanders asks Facebook-users for the “small favor” of adding their name to support the campaign. Clicking on the link redirects you to a form on Sanders’ website where one can add their information and potentially donate money to the campaign (Add your name to endorse our campaign, n.d.). The sentence at the beginning of the advertisement - “I got a small favor to ask of you” - has become a signature phrase for Sanders, and even become a huge internet meme (Sung, 2020). This particular advertisement on its own has 34 different versions and a total of 434 identical campaigns were distributed on Facebook among different geographical target groups. Sanders' campaign spent a total of $13,570,105 on Facebook and Instagram advertisements between May 2018 and May 2020 (Ad Library, n.d.).

When entering the front page of Sanders' website, the first thing visitors see is the sign-up box next to a picture of Sanders, with an ‘about’ box directly above. This layout allows people to sign up for the newsletter or find relevant information without reading through the rest of the website. They can easily and quickly fill in their personal information and receive all the information that they need. Importantly, the ‘Donate’ button and the sign-up button are both red, while no other links or buttons on the website are. This draws one’s attention directly to these buttons (Figure 3). The interface of the website is thus designed to attract visitors to those pages that are most important for the campaign.

Characteristics of Sanders' Newsletters

Sanders' newsletters go out almost daily and nearly always ask for a small contribution in addition to updating followers about the campaign. What is particularly striking is that the newsletters have an informal style and are quite to the point.

The informality and directness can be seen in the email subjects that are used. The four newsletters I received between March 9 and March 15, 2020 all have a similar style and pattern in their subjects: “What I just told the press about our campaign”, “I hope you are doing well”, “I will explain more shortly”, and “everything is changing.” There is a casualness here - the salutation starts with ‘I’ and the style is personal and informal. The ‘I’ makes readers feel like just one person is addressing them, and creates the illusion that Sanders is addressing them personally. Moreover, the subjects do not reveal the content of the newsletter itself, creating curiosity and making the receiver want to read the entire email.

Further, the informal tone carries over into the actual newsletters. Almost all of the emails are addressed to "Friends." This is of course a very personal and informal way of approaching one’s followers, and refers to the aim of creating (the feel of) a friendly, close-knit community. His message about building a movement aligns with his language use. Bond & Exley further explain that:

"If you choose the small-dollar path, the people you get money from will also play a part in determining your objectives, strategies, and messaging. If you find it hard to fundraise from your mass base, then probably there is a problem with your leadership or your plan or both! You will then have to keep changing until you connect with and finally communicate in a meaningful way with the people you are proposing to serve. The time you spend with your base will allow you to get to know your people better. You will be able to use that time to recruit amazing leaders out of your base. By relying on those leaders, you will find that you need fewer resources to get much more done than you could have relying solely on paid staff" (2016, p. 70).

This reflects Sanders’ team's approach to newsletter readers and the language style used in these emails. For instance, the recurrent use of words like ‘Friends’, ‘I’ and ‘We’ show that Sanders’ campaign is bottom-up instead of top-down, i.e., big organizing. Further, some emails are so informal as to skip salutations altogether. For example, an email sent on March 6, 2020 regarding the decision to take a financial risk, skips the acknowledgment and starts directly with, “I had to make a very tough decision" (Figure 6). Moreover, this formulation gives the impression that readers are receiving exclusive, inside information directly from Sanders – the "I" – and updates on what is going on "behind the scenes". This supports a feeling of familiarity and being a part of a movement among readers.

Salutation in email with “Friends

No acknowledgment in the email, straight to the point.

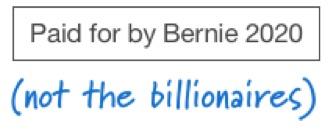

This emphasis on community shows how these emails are not only trying to solicit donations or inform readers but also have a ‘phatic’ function. Varis & Blommaert define phatic forms of interaction as being: “…characterized by relatively low levels of ‘information’ and ‘meaning’" (2015, p. 31). Phatic communication “is the language function which stresses on the presence of contact between the sender (speaker) and the receiver (hearer) of the message" (Jakobson, 1960, as cited in Jumanto, 2014). The newsletters' phatic discourse creates a feeling of equality between Sanders and his followers and places the focus on the bottom-up, community-based nature of his campaign. This helps create a shared group identity and feeling of belonging. The text “Paid for by Bernie 2020 (not the billionaires)” is added to every newsletter, showing that his followers are the ones funding the campaign (Figure 7).

Text indicating that the campaign is paid for by Bernie Sanders and his followers, and not by billionaires

Furthermore, the content of the newsletters is rather standard and does not differentiate often. The newsletters are honest, brief, to the point, and written in an accessible style. The content of the newsletters reflects the use of phatic forms of communication, as the messages often do not include much relevant content (Varis & Blommaert, 2015, p. 32) but are crucial in building a feeling of belonging. The newsletters help create a movement identity.

There are a few basic elements that return in every email. First, the emails start with a short explanation of how the campaign is going. According to Bond and Exley this is particularly important because, “If you want to overthrow the system, or any part of it, you still need to start with the people" (2016, p. 67). In big organizing, the biggest motivation is the people: “(…) revolutions usually are begun with no central source of funding. Start with people, not with money” (Bond & Exley, 2016, p. 67). Providing people with regular and consistent updates and information keeps possible voters and contributors interested and engaged.

Second, most emails then proceed to ask the reader to contribute $2.70 to the campaign, making it clear how every single contribution makes a difference. Additionally, the emails all end with a large blue “CONTRIBUTE” button (Figure 8) that redirects to the donation webpage.The way the newsletters are phrased invites the reader to contribute to the campaign. Further this phrasing gives the reader the impression that they are doing something important because ultimately the supporters are the ones financing the campaign and determining Sanders’ success. Bond and Exley touch on this in their book as well, stating that in 2012, “while the other campaign had big-dollar contributors and all of the resources that the establishment could muster, we had people. Lots of them” (2016, p. 49). Sanders’ team has thus refined their way of getting people to contribute to the campaign. This is key because money is incredibly important in U.S. politics.

“CONTRIBUTE” button, which links directly to a webpage to donate to the campaign

Finally, the newsletters' regularity and quantity is key. As previously mentioned, the emails are almost daily. This repetition is an important factor when growing a political campaign (Bond & Exley, 2016, p. 153). The phatic communication and quantity of the newsletters exemplifies what Bond and Exley write about succeeding in big organizing: “we need to talk to everyone – not just narrow slices of assumed swing voters – about what we want to achieve” (2016, p. 5). This is because Sanders’ campaign ultimately runs on crowdfunding, or, “the collective cooperation by people who pool their funds, usually via the Internet, to support efforts initiated by other people or organizations” (Dresner, 2014, p. xi). Crowdfunding aligns with Bond and Exley's adage for building a revolution: "Start with people, not with money" (2016, p. 67).

Ultimately, the goal of the newsletters is to collect as many donations as possible, as is evidenced by the many options to donate and contribute to the campaign. Moreover, it seems to be working: in the first 24 hours of Sanders’ 2020 campaign, he raised $5.9 million (Gambino, 2019). Within the first six weeks, the newsletters helped raise more than $18 million and sign up one million volunteers (Stewart, 2019). These crowdfunded donations “are an early sign of the Vermont senator’s fundraising powers in what is expected to be a competitive – and expensive – primary race to clinch the Democratic nomination” (Gambino, 2019). Importantly, fundraising allows a candidate to finance things like advertising, leading to more support and more votes. As Philip Bump clarifies in an article from the 2012 elections, money practically buys votes in U.S. politics. As a race grows tighter, each vote grows more expensive, meaning that the most important votes cost more. Further, the more a candidate can out-fundraise his opponent, the more likely he is to defeat that opponent (Bump, 2013).

How much money a campaign has raised can be used to measure its success.

Nevertheless, money is not solely important for financing a campaign. How much money a campaign has raised can be used to measure its success. This can be illustrated with an example from a 2015 debate. During this debate, Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton was continuously asked about her leaked emails. When it was Sanders’ turn to talk, he took the stage, saying “the American people are sick of hearing about your damn emails” (Brown, 2015). Sanders’ campaign team then posted a video of that part of the debate to their website, asking people to donate to the campaign. Sanders’ quip helped raise $1.3 million in just 4 hours following the debate. There were 37,600 individual contributions, with an average donation of $34.58. At the peak, there was an average of 10.25 contributions per second (Brown, 2015). Sanders' success in this debate is thus indicated by the number of donations made.

This example illustrates how success in U.S. politics is measured by fundraising. In this case, Sanders’ message was well received well among many debate viewers, resulting in a peak in crowdfunding. Less or no fundraising would indicate that Sanders’ message in that particular debate was not as strong. This would then be communicated through media as well (Lempert & Silverstein, 2012, p. 55), resulting in a negative message for the politician.

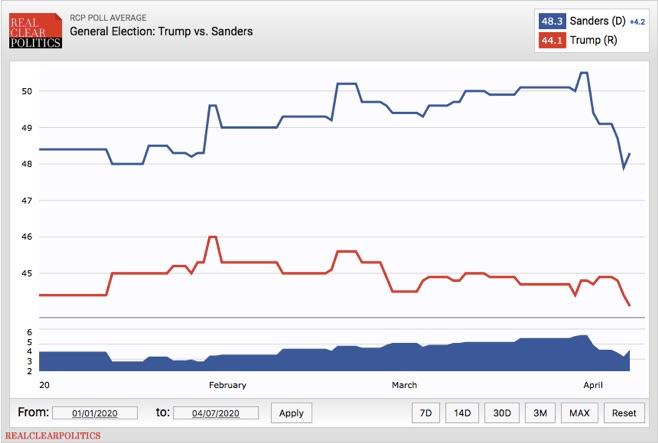

Popularity poll, Bernie Sanders versus Donald Trump

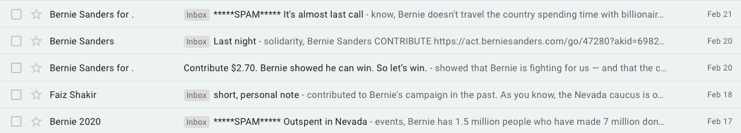

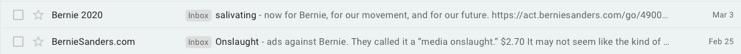

To research whether or not the quantity of the newsletters is influenced by Bernie Sanders’ popularity, I analyzed two weeks of Sanders’ 2020 campaign in more detail. In a poll comparing Bernie Sanders with Donald Trump (Figure 13), there are moments where Sanders’ popularity rises and then falls again. From Monday, February 17th until Sunday, February 23rd, Sanders' score increased quite rapidly, but dipped again the following week. The emails from this week described the importance of donations at that specific moment, because super-PACs were overshadowing Sanders’ campaign. Comparing the two weeks, five emails were sent when Sanders’ popularity was rising (Figure 14), but only two emails were sent (Figure 15) when his popularity fell. This illustrates a potentially positive relationship between Sanders’ popularity and the quantity of newsletters. Periods were many newsletters are being shared align with a rise in the popularity of Bernie Sanders in the polls, and vice versa.

Newsletters from week 8

Newsletters from week 9

Thus, the characteristics of the newsletters allow Bernie Sanders to generate contributions to his campaign. This is important because Sanders’ success is directly determined by the money he collects through donations. Sanders’ accomplishments in crowdfunding and big organizing are linked to the idea that people are listening to what he is saying and that his message works.

References

Ad Library. (n.d.). Retrieved May 21, 2020.

Ad Library. (n.d.). Retrieved May 9, 2020.

Add your name to endorse our campaign. (n.d.). Retrieved May 21, 2020.

Bond, B., & Exley, Z. (2016). Rules for Revolutionaries. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Brown, N. (October 14, 2015). Bernie Sanders sparks the most social media buzz post-debate. MSNBC.

Bump, P. (November 11, 2013). Does More Campaign Money Actually Buy More Votes An Investigation. The Atlantic.

Dresner, S. (2014). Crowdfunding: a guide to raising capital on the internet. Wiley.

Gambino, L. (March 3 ,2020). 'He's working for it': why Latinos are rallying behind Sanders. The Guardian.

Jumanto. (2014). Phatic Communication: How English Native Speakers Create Ties of Union. American Journal of Linguistics, 3(1), 9–16.

Lempert, M. & Silverstein, M. (2012). Creatures of Politics: Media, Message, and the American Presidency. Indiana University Press.

Stewart, E. (July 5, 2019). Bernie Sanders is winning the internet. Will it win him the White House?. VOX.

Sung, M. (February 6, 2020). Bernie Sanders asking for your support is a meme for the entire campaign season. Mashable.

Varis, P., & Blommaert, J. (2015). Conviviality and collectives on social media: Virality, memes, and new social structures. Multilingual Margins: A Journal of Multilingualism from the Periphery, 2(1), 31–45.