The November 13 Paris attacks

Terrorism through online infrastructures

Loads of people got involved in the Paris attacks: perpetrators, Islamic State, vitcims, and the general public. In this article, these groups of people are brought in relation to globalization and escpecially to online infrastructures.

November 13: attack on Paris

'Fluctuat Nec Mergitur' is the Latin motto of the city of Paris. Seen on the walls of official buildings and metro stations in the capital, its meaning was not widely understood until the terrorist attacks of November 13th, 2015. Parisians began using it in messages of resistance for their attackers. Fluctuat Nec Mergitur means: ‘Tossed but not sunk’, or: ‘Beaten by the waves, but not sunk.’ The ship being used as a metaphor for the people who lost their lives during these attacks, the spirits of the people in Paris will never be sunk.

The Latin motto written on a wall in the city center of Paris

Fluctuat Nec Mergitur has also been used as the title for the tripartite Netflix documentary about the 13 November attacks, the full title of the series being: ‘13 Novembre: Fluctuat Nec Mergitur’. The documentary tells the story of those who survived the heinous acts, each individual describing his or her own experience of that night.

Whilst watching ‘13 Novembre: Fluctuat Nec Mergitur’, urgent personal questions arise: how could this have happened? How could such a big group of terrorists unite and through what (online) infrastructures? And what was the role of these online infrastructures when it comes to the victims and the general public?

In this article, the role of global online infrastructures in relation to different actors/aspects of terrorism will be discussed in the context of the 2015 Paris attacks. The actors/aspects which will be focused on are the perpetrators, the terrorist organizations, the victims, and the general public.

The Paris attacks on the dark alleys of the web

Due to globalization and technological improvements, almost everyone all around the globe has access to the internet. The internet is part of, and has often been envisioned as, what Jurgen Habermas called the ‘public sphere’. The public sphere can be described as a domain of our social life where such a thing as public opinion can be formed and where citizens deal with matters of general interest, without being subject to coercion. It is a ‘space’ where citizens engage directly, albeit digitally, in participatory democracy to bring about change (McKee, 2004, 6). The web is an important part of this public sphere.

Because of the easy accessability of the internet, it can be used for every purpose anyone has, unfortunately also for darker purposes.

The web can be seen as an unrestricted digital landscape that allows several groups to thrive. This unrestrictedness, however, also has its downside. Because of the easy accessability of the internet, it can be used for every purpose anyone has, unfortunately also for darker purposes.

A darker element that has emerged from this public or democratic sphere is the resurgence and successful transformation of hate groups across the web. The authors and participants of these groups have managed to adapt their movements into the social networking, political blogging, and information-providing contexts of the modern online community. The internet functions as a digital infrastructure for these hate groups.

The viewpoints made by these hate groups can be so convincing, appealing, and relatable to certain individuals that it can lead to radicalization. Radicalization can be defined as the action or the process of causing someone to adopt radical positions on political or social issues.

Since 9/11, many claims have been made about the role of media, particularly new communication technologies, in encouraging the process of radicalization: the embracing of extremist views, which manifests itself in the form of terrorist violence. In the following, the focus will therefore be on online radicalization, in particular on online jihadist radicalization by Islamic State.

Islamic State's online radicalization

Online radicalization is a highly complex and individualized process, often shaped by personal factors. Websites and other kinds of online organizations fulfill the needs of their audiences which have their offline lives have somehow not adequately met.

Looking at their online radicalization manners, Islamic State uses so-called virtual planners (Archetti, 2015, 55). Virtual planners are individuals who, using social media and encrypted online messaging platforms, connect with potential attackers in countries outside of Islamic State-held territory and guide them through the execution of terrorist attacks.

By using virtual planners, the Islamic State drastically expands its reach and its ability to manage and plan attacks overseas.

By using virtual planners, the Islamic State drastically expands its reach and its ability to manage and plan attacks overseas. The Islamic State's virtual planners are usually located in the territory the group holds, are skilled in the use of online sources and have ties to the leadership of the organization, in particular the intelligence wing, the Emni, which will be discussed below.

The identification or radicalization progress through virtual planners goes as follows: virtual planners find vocal supporters of Islamic State on social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, they initiate contact and conversation with them via encrypted messaging platforms such as Telegram, SureSpot, and WhatsApp, and instill them with technical and/or operational knowledge necessary to begin planning an attack.

The Paris attacks

November 13, 2015 is an example of a day where the whole world got to see the execution of such a planned attack by Islamic State. In a timespan of ‘just’ 44 minutes, three groups of men were responsible for the launching of six distinct attacks throughout the French capital: three suicide bombings in one attack, a fourth suicide bombing in another attack and shootings at four locations in four seperate attacks.

The French president Francois Hollande was inside the Stade de France watching a friendly soccer game between France and Germany among thousands of other people, when three explosions occured outside the stadium. Another suidice bombing and several shootings happened at several bars, restaurants, and a concert hall, attacking citizens and tourists enjoying their time in the French capital.

The attackers killed 130 people, including 90 at the Bataclan theatre. Over 400 people were injured, almost 100 seriously. Seven of the attackers also died during the Paris attacks (Gilles, 2017, 225)

The 13 November Paris attacks were claimed by Islamic State. When an attack is considered ‘claimed’, it means that a jihadist group, in this case Islamic State, can declare that perpetrators were supporters of, or inspired by their group, mostly after the attack via its media outlets. An example of this online media outlet is Islamic State's Dabiq, also known as their online magazine.

Al Qaeda, an example of another jihadist terrorist group, would immediately claim responsability after an attack (as opposed to Islamic State, they usually claim responsability a few days after the attack). This claiming often goes via a ‘martyrdom video’. This is a video featuring the attackers explaining the reasons for their attacks.

It has been made clear by various corroborated pieces of intelligence that the Emni was responsible for training and recruiting the jihadists who carried out the November 2015 Paris attacks (Lesquesne, 2016, 310). The Emni is the intelligence unit of Islamic State. They are responsible for planning and managing external operations, thus attacks outside Islamic State’s territory including Western countries.

The formation of the Emni, which is a francophone unit, is likely the main reason that France and Belgium have suffered a disproportionate number of attacks, as the members of the unit have leveraged their own personal contacts (both offline and online) in those two countries. The Emni is also heavily involved in the creation of pro-Islamic State propaganda, especially media encouraging potential jihadists to conduct attacks outside of Islamic State territory.

Since the advent of social media apparatuses, potential recruits and ideological adherents are much more quickly added into the existing online communities of extremists.

Previously, jihadist groups would have needed months or even years to fully intergrate a new member into a terrorist cell. Extremist websites used to be primarily restricted from the general public. A potential recruit had to search out and befriend members of radical forums in order to be accepted and subsequently gain access to the functionality of the sites.

Now, aspriring terrorists only need to open their laptop and connect to the internet. Since the advent of social media apparatuses, potential recruits and ideological adherents are much more quickly added into the existing online communities of extremists. The interactive online experience can thus accelerate the radicalization and mobilization process.

Until now, this article was mainly about the role of online infrastructure in relation to the perpetrators and Islamic State before the November Paris attacks. The following will discuss the role of online infrastructures in relation to the victims and the general public of the attacks.

The online aftermath of the Paris attacks

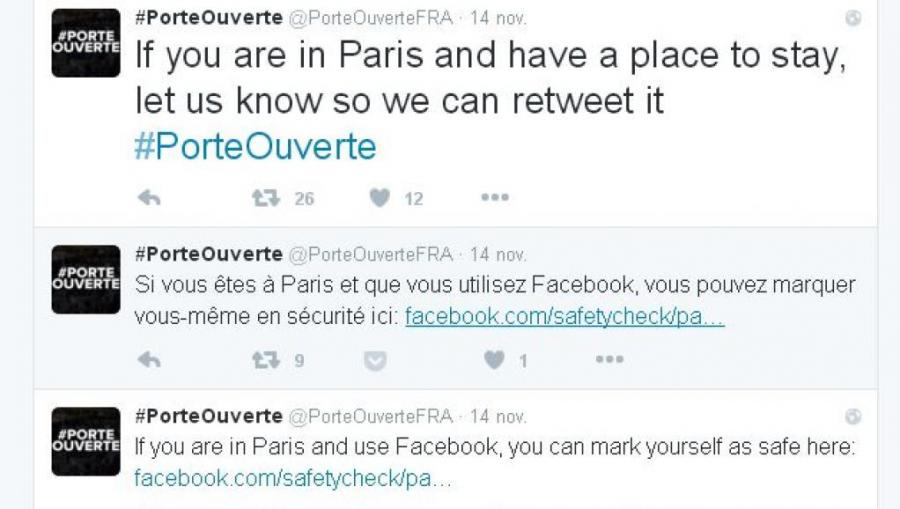

On the social media platform Twitter, new hashtags were made and used to show support to the victims of the Paris attacks. However, they were also used to create a connection between people, showing the terrorists that the world stands together. During the 13 November attacks, multiple locations were targeted and many people were looking for a safe place to take shelter. Parisians started using the hashtag on Twitter #porteouverte, which literally means ‘open door’. This was a signal to the people in danger to provide them with a safe place to stay that night.

Another hashtag that was used at the night of the Paris attacks and the days after the attacks, was #JesuisParis. This hashtag was first used after the attack on the satirical weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo earlier that year in January. The hashtag originally started as #JesuisCharlie, to show support and sympathy to those who lost their lives at the Charlie Hebdo offices that day.

The hashtag soon changed into #JesuisParis, because only two days after the Charlie Hebdo shooting, two other attacks occured in Paris, killing other people. On the social media platform Facebook, various groups were established that people could like or join to show support and respect for the victims of the attacks. Also on Facebook, messages, reports, and videos about the attacks went viral. For example, on the night of the attacks, an ID photo went viral of an attacker who was still at large. Many people were encouraged to share the photo to help find the man.

Example of a #porteouverte tweet during the night of the attacks

On June 1st, the American media-services provider Netflix published a tripartite documentary about the 13 November Paris attacks. As mentioned above, the Netflix documentary is called 13 Novembre: Fluctuat Nec Mergitur, quoting the motto of the French capital. The documentary tells the story of several survivors of that night, survivors or eyewitnesses of the bombings near the Stade de France, the shootings in several bars and restaurants, and the survivors of the Bataclan hostage (Digiacomi, 2018). 13 Novembre: Fluctuat Nec Mergitur follows the chronology of the events and shares the testimony of the survivors and of the leaders of the French government.

The producers of the Netflix documentary, Jules and Gédéon Naudet, already created a documentary about the September 11 attacks in New York and found a lot of similarities between both attacks. They state that both attacks can be described as ‘never ending attacks’, ‘The September 11 attacks contained one plane, two planes three planes.The November 13 attacks had the Stade de France, the terraces, the Bataclan..’ This is one of the most important reasons why the Naudet brothers wanted and found the necessity to create this poignant tripartite documentary.

Online infrastructures and the Paris Attacks

The 2015 Paris attacks were terrorist attacks with enormous effects. Not only Paris, but the whole world got involved by sharing compassion to France and the victims. Other countries also got involved on another level: because the terrorist threat was extremely high in France during that time, the terrorist threat in other countries also rose to the highest level.

This is globalization in full swing: an event in one place has repercussions on, and gets connected with, large parts of the world through the deployment of an online infrastructure. The use of online infrastructures can have different goals to groups or people. Islamic State and its perpetrators used online infrastructures to expand their ideology and to organize and claim responsability for their actions.

The victims and the general public of the Paris attacks used it to show support and to commemorate the heinous acts. And in the wake of these attacks, goverments across the world intensified the use of these online infrastructures to prevent terrorist attacks. After all, organizations such as Islamic State, as well as numerous other hate groups, exploit the affordances of an Internet which is open to everyone.

So the question inevitably arises: must the darker alleys of the Web remain accessible to all? No clear answer to this huge question is available so far.

References

Archetti, Cristina (2015). “Terrorism, Communication and New Media: Explaining Radicalization in the Digital Age.” Perspectives on Terrorism, vol. 9, no. 1, 49-59. JSTOR.

Digiacomi, Claire (2018). “ ‘13 Novembre: Fluctuat Nec Mergitur’ sur Netflix: pourquoi le 11-Septembre de ces réalisateurs a fait de ce docu ce qu’il est.” Huffpost 1 June 2018. Web. 28 Nov. 2018.

Kepel, Gilles (2017). Terror in France : The Rise of Jihad in the West. Princeton University Press, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Klein, Adam (2017). “Fanaticism, Racism, and Rage Online: Corrupting the Digital Sphere." New York City, NY, USA. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

Lequesne, Christian (2016). “French Foreign and security challenges after the Paris terrorist attacks.” Contemporary Security Policy, vol. 37, no. 2, 2016, pp. 306-318. Taylor & Francis Online, Taylor and Francis Online.

McKee, Alan (2004). The Public Sphere: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press(or 2012).