The Pro-Choice Movement: A brief ideological history of abortion

In the United States of America, attacks on the right to abortion have been rising ever since 2011 which goes against the ideology of the Pro-Choice movement. In Texas, as well as other Republican-dominated states, lawmakers are trying to find ways to restrict abortion access. As recently as September 2021, an anti-abortion bill has come into effect in the state of Texas which states that abortions cannot be performed after the sixth week of pregnancy. As a result, the Pro-Choice movement that defends the reproductive rights of menstruating people has become more active than ever.

In this introductory article discussing the historical background of the contemporary American abortion battle, we will go in-depth on the history of abortion. It will be explained that the abortion debate is rooted both in pro-life and pro-choice ideologies that have existed and been in conflict with one another for centuries. In doing so, we will focus on how Victorian America was transformed from a pro-choice to a pro-life society, thereby demonstrating why the introduction of multiple anti-abortion policies in the late 1800s can be considered anti-hegemonic. Furthermore, we will argue that the abortion debate of this era was a political fight in the name of medicine, morality, normativity, and life. Lastly, we will discuss how the Court’s decision to legalise abortion in Roe vs Wade came into being and how the rise of pro-lifers has manifested itself in the introduction of a new anti-abortion bill, namely the Texas Heartbeat Act.

The origin of the Pro-Choice movement: abortion ideology until 1850

Ideology is defined as ‘any set of socially structured ideas guiding behaviour and thought in particular domains of life’. As aforementioned, in the domain of abortion, we are faced with two opposing ideologies; that of pro-choice and pro-life. Despite what most may think, the pro-life ideology that abortion is murder is a relatively recent one (Luker, 1985). Of course, pro-life beliefs have existed ever since antiquity, but so have pro-choice ones, and they were actually dominant in society for quite some centuries. To demonstrate this, we will use Luker’s Abortion and the Politics of Motherhood (1985) in the following paragraphs, which gives a summary of abortion history and ideology throughout the years.

Accordion to Kristin Luker (1985), there were two adversarial schools in ancient Greece when it came to abortion. The Pythagoreans held that abortion was wrong because they believed the embryo to be the moral equivalent of the child it would become, which meant abortion equated to murder. This school was the predecessor of the current pro-life ideology. The ancient Stoics, however, found embryos to be of a different moral order than already-born children and, consequently, considered abortion not to be equivalent to murder. This school formed the predecessor of the pro-choice ideology. In the Roman empire, abortion was widespread and occurred on a frequent basis. Legal regulation, however, was essentially nonexistent. Roman law held that the child in the belly of its mother was not a person and therefore abortion could not be murder. This is more reminiscent of pro-choice ideology than it is of pro-life ideology.

Amongst the early Christians, abortion was widely denounced but the legal and moral treatment of it was never consistent with this rhetoric (Luker, 1985). For example, induced abortion is not mentioned in the Christian or the Jewish bible. Indeed, abortion was denounced in early Christian writings but church councils, which were tasked with specifying the legal groundwork for Christian communities, only gave penalties to women who had an abortion after having committed sexual crimes such as prostitution or adultery. Moreover, different sources of church teachings and laws don’t even agree on whether these penalties should be given in the first place, nor on the matter of whether early abortion is ever really wrong.

As such, from 200 A.D. onward, Christians were divided as to whether abortion was, in fact, murder.

The belief that abortion is not murder is hegemonic in American Victorian society

In the Middle Ages, more specifically in the year 1100 A.D., this debate was clarified by Ivo of Chartres, a prominent church scholar, who denounced abortion but declared that abortion of the ‘unformed’ embryo was not homicide. This stance was reiterated fifty years later by Gratian, in a work that would become the basis of canon law for the next seven hundred years. In practice, Gratian’s rulings meant that Catholic canon law and moral theology did not treat abortion in the first trimester as murder. This law and theology were the legal and moral standard in the Western world, meaning that abortion was not believed to be murder in Western countries (Luker, 1985).

As a result, right before and during the Victorian era, there were no state laws against abortion in the USA (Luker, 1985; Mohr, 1979). The common law held that abortion was not a crime prior to ‘’quickening’’ which was the moment when the mother first felt her baby move (Luker, 1985; see also Weingarten, 2014; Mohr, 1979) and also the moment after which most women believed life truly began (Reagan, 1997). Only late abortions could therefore be prosecuted, but even then it was never equated with murder (Mohr, 1979; Luker, 1985). In fact, until the second half of the nineteenth century, there was a good amount of advertising for abortion services and medicines, which also led to an increase in the number of abortions.

What we see in this era, is that the belief that abortion is not murder is hegemonic in American Victorian society. Hegemony refers to 'the dominance of certain ideas, images, discourses, and ideologies, either generally or in specific domains'. The predecessor of the pro-choice ideology was dominant in the Victorian era and essentially seen as ‘normal’, which means the belief was not at all questioned in society and therefore had a lot of so-called soft power, that is cultural power.

Abortion ideology after 1850

In the second half of the nineteenth century, we see an interesting shift happening from a society that believes abortion is not murder and therefore should be legal to a society that finds abortion immoral and wants to restrict it. As we have mentioned before, nineteenth-century America did not inherit an anti-abortion climate. On the contrary, the ideology that would later be known as the pro-choice ideology was hegemonic in this period of time. So what happened during the 1850s that so radically changed the abortion climate in the USA.

According to Kristin Luker in Abortion and the Politics of Motherhood (1985), the most prominent group that caused a change in the abortion status surprisingly consisted of physicians, who actively petitioned state legislatures to pass anti-abortion laws. Physicians who were part of the American Medical Society adopted the position of Horatio R. Storer, physician and vocal member of the AMA, whose mission was to change the American abortion law. In his work On Criminal Abortion in America, Storer claims that ''by the moral law, the wilful killing of a human being at any stage is murder,'' and explains that ''if there be life, then also the existence, however undeveloped, of an intellectual, moral, and spiritual nature, the inalienable attribute of humanity, is applied'' (Weingarten, 2014). This work introduced a new form of biopolitics (Foucault, 2010) that would privilege the protection of the fetus over the protection of the pregnant woman.

Physicians argued that American women were committing a moral crime that was based on ignorance about the value of embryonic life

From that moment on, the goal of the American physicians was to change public opinion on abortion, which in their view was morally wrong and medically dangerous. The physicians argued that American women were committing a moral crime that was based on ignorance about the value of embryonic life and that they were obliged to intervene to save women from their own ignorance. It is appropriate to think of the physicians as moral crusaders or crusading reformers, as, according to Howard Becker in Outsiders (1963, p. 148), they "are interested in forcing their own morals on others and (...) believe their mission is a holy one’’. They truly believed they were ‘’attempting to provide the conditions for a better way of life for people prevented from realizing a truly good life'' by medicalising abortion and fighting for its riddance. They fought to abnormalize the practice of abortion by positioning themselves as experts, which resulted in a successful crusade.

In the process, they also created outsiders or ‘rule-breakers’. According to Becker (1963, pp. 2-3), these people are ‘’deviant from group rules,’’ and "may not accept the rule by which he is being judged and may not regard those who judge him as either competent or legitimately entitled to do so''. In this case, women wanting or undergoing an abortion do not obey the rule that is set by the medical crusaders, and are, therefore, labeled as outsiders. However, it is important to note that, according to Becker (1963), deviance is a social construct. Even though these physicians claimed to be experts and thus to possess the truth on ‘the other’, what is seen as normal or abnormal is always socially determined and thus not generally ‘true’.

Through the construction of women as outsiders and their coding of abortion as a strictly medical matter, the American physicians of the nineteenth century managed to transform the abortion question of their era into a political fight in the name of medicine and morality

The physicians claimed to possess scientific evidence which showed that embryos were a child from conception and onward (Luker, 1985). Abortion was now framed according to a biopolitical logic (Weingarten, 2014). This medicalisation and biopoliticisation of abortion ruled women unfit to make decisions over their own pregnancy, which shows exactly how physicians were able to push their own agenda so well. They made themselves the only valid voices in the debate by claiming to be the only ones having access to the truth. As Dr. Joseph Taber Johnson argued, the responsibility for enlightening the public about the matter of abortion lay with the medical profession (Raegan, 1997). He felt it was the duty of the nation’s doctors, particularly specialists in obstetrics and gynaecology, to correct the popular beliefs about the life of a fetus. This was done, amongst others, through the reeducation of American women about the immorality and dangers of abortion by physicians themselves (Reagan, 1997), as they portrayed themselves to be the only ones having access to the medical knowledge, the truth, needed to make ‘correct’ decisions about abortion.

And so, abortion was medicalised and biopoliticised by American physicians through, what Goodwin (1994) describes as, the discursive practice of ‘coding.’ Discursive practices are "used by members of a profession to shape events in the domains subject to their professional scrutiny" (Goodwin, 1994, p. 606). One such practice is that of coding, which "transforms phenomena observed in a specific setting into the objects of knowledge that animate the discourse of a profession" (Goodwin, 1994, p. 606). In this case, the physicians belonging to the medical profession used the discursive practice of coding to shape the way American women thought about abortion, a domain subject to the professional scrutiny of these physicians. By transforming the phenomenon of abortion into the objects of knowledge that animate the discourse of the medical profession, i.e. by speaking about abortion in medical and biopolitical terms, American physicians eliminated women from the abortion debate, ruling them unfit to make correct decisions about such ‘medical’ matters.

All of this considered, we can conclude that, through the construction of women as outsiders and their coding of abortion as a strictly medical matter, the American physicians of the nineteenth century managed to transform the abortion question of their era into a political fight in the name of medicine and morality. In doing so, they managed to factor out women in the debate about their own bodies and to criminalise a practise that had previously been ‘normal'.

The reintroduction of the Pro-Choice ideology

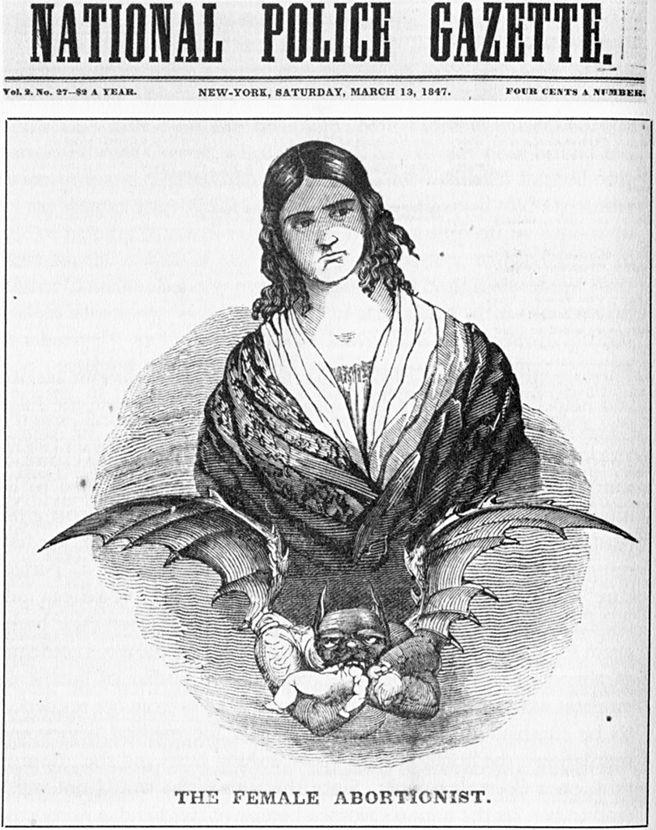

In 1847, a female physician called Madame Restell, who provided women with ‘preventative powder’ and ‘female monthly pills’, which would induce miscarriages, or even surgical abortion procedures, was arrested. The New York State legislature had passed a bill two years earlier which held that providing abortions or abortion-inducing medicines at any stage of pregnancy was punishable by a year in prison. Restell was found guilty of misdemeanour procurement and was sentenced to a year in prison.

When she was released, she continued her practice, only this time around she would no longer offer surgical abortions. As can be seen in Figure 1 below, Restell (here referred to as ‘the female abortionist’) was depicted as evil. Despite the many women that were grateful for her services, Madame Restell was a rather controversial figure in this anti-abortion era and she was often called ‘the wickedest woman in New York' (Abbott, 2012).

Figure 1: Madame Restell's arrest as reported in the National Police Gazette

Following this anti-abortion trend, a series of over 40 anti-abortion laws were passed between 1860 and 1880 that greatly restricted abortion and even made abortion prior to quickening a crime (Luker, 1985). Then in 1890, anti-abortion laws became a standard part of statute law in the USA, which were accepted as a legitimate part of life until the 1950s.

In the early 1970s, a lot of pressure had built up in favour of changing the anti-abortion policies that were set in place between the 1860s and 1880s. In his book Abortion in America: The origins and evolution of national policy (1979), James C. Mohr identifies numerous causes for this:

- Firstly, there was a huge risk of overpopulation, which made policymakers tolerant of any reasonably safe methods of contraception. Contraception, however, was not enough to solve the crisis, which is why many Americans later accepted abortion as a method to fight overpopulation.

- A second cause that helped change American abortion policy was an increasing concern for what was called the quality of life, as distinguished from biological life. Americans started to struggle with the question of whether all forms of life are worth the social, emotional, and financial costs of maintaining them.

- Third, the advocates of women's rights changed their attitudes toward abortion. Most feminists in the nineteenth century had avoided the issue, while male policymakers passed laws that tried to force all women to carry a fetus to full term. The women's movement of the 1960s and 1970s, in contrast, declared that women had an inalienable right to control all their own bodily functions, and asked the Supreme Court to confirm that right unconditionally in the Roe vs Wade case when it came to pregnancy.

- The fourth source of pressure came from new medical data in the area of female safety, which became available in the 1950s. It was discovered that abortion was less dangerous than previously thought in the 1890s.

- And fifth, a big number of American women continued to seek and to have abortions despite the laws designed to make them unavailable.

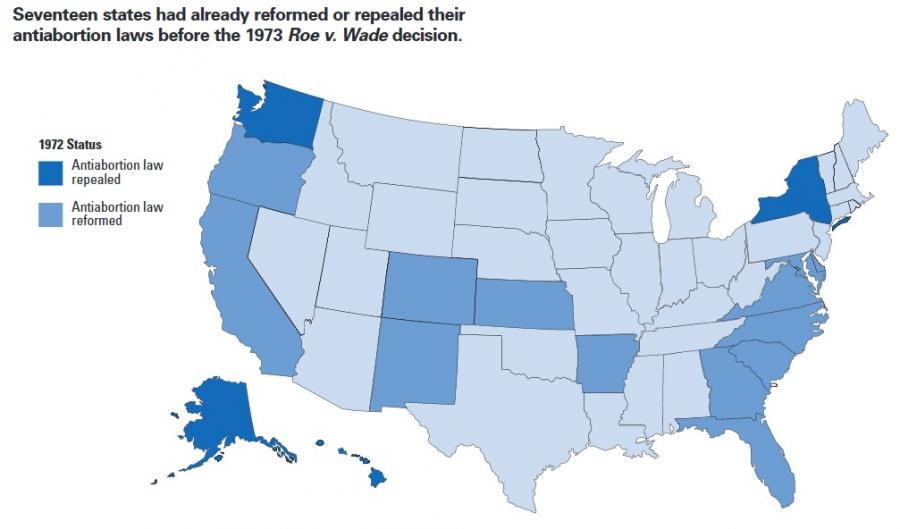

This aforementioned pressure resulted in seventeen states having reformed or repealed their anti-abortion laws in 1972, as shown in Figure 2. The revolutionary change, however, came only after 1973 when the United States Supreme Court ruled in Roe vs Wade that a Texas anti-abortion statute was unconstitutional (Mohr, 1979).

Figure 2: Illustration of the change in the abortion climate of the USA in the early 1970s.

What we can now conclude is that what was seen as a normal or hegemonic practice until the first half of the nineteenth century - namely that abortion is not murder and should be available to all women - became abnormal in the second half of the nineteenth century. Anti-hegemonic physicians pushed an anti-abortion agenda which led to an anti-abortion society and multiple anti-abortion laws being passed. Then, in the 1970s there was another cultural shift that led to the reintroduction of the pro-choice ideology in 1973, when Roe vs Wade made abortion a constitutional right across the nation (Planned Parenthood, n.d.).

The far-reaching change: Roe vs Wade

The roots of the contemporary Pro-Choice movement lie in the aforementioned Supreme Court Case Roe vs Wade that took place on January 22nd, 1973. The case had been filed by Norma McCorvey, who used the name ‘Jane Roe’ as a pseudonym to protect her own privacy. McCorvey was an unmarried woman who wanted to safely and legally end her pregnancy but could not do so because the state of Texas prohibited abortion unless a woman’s life was at risk (Planned Parenthood, 2014).

In the Roe case, the Supreme Court overruled the Texas law and recognised that the constitutional right to privacy had enough room to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to end her pregnancy (Planned Parenthood, 2014). The Court found that the right for women to make decisions about their own privacy deserved the utmost constitutional protection. In doing so, it legalised abortion across the entire country and made it a constitutional right.

It was decided to divide pregnancy into trimesters. During the first of these, the decision whether or not to terminate a pregnancy was up to the woman herself; during the second of these, the state could regulate abortions - although not ban them - should the mother’s life be at risk. During the third and last trimester, the fetus was seen as viable and, therefore, the state could outlaw abortions, except for instances when the mother’s life was at risk (Legal Information Institute, n.d.).

The abortion battle is now and has always been, a political fight in the name of medicine and morality

According to James C. Mohr's Abortion in America: The Origins and Evolution of National Policy (1979), the Court’s decision to legalize abortion in 1973 was not met by unanimous support from the American public. Some citizens, and especially feminists, believed the Court did not go far enough and wished for abortion to be declared ‘unconditionally permissible’ in the first, second, and third trimester. A great number of citizens, on the other hand, wished to re-establish the anti-abortion policies pushed forward by influential physicians in the 1900s. Some even wanted to strengthen these policies. This is why the anti-abortion ‘right-to-life’ movement, which was supported by many Catholic lay and clerical organizations, gained momentum. Thus, the abortion battle is now and has always been, a political fight in the name of medicine and morality.

Later, the description ‘pro-life’ was adopted instead of ‘anti-abortion’, so as to make it seem the movement is concerned about the taking of human life, instead of wanting to restrict women’s reproductive rights (Assendelft et al., 1998). This is part of pro-life's discursive battle for meaning, which is waged over the definition of words, the interpretation of facts, the understanding of the ideology or the general image of the movement (Maly, 2016). By changing the description of the movement to something that we all support, as no one can oppose being ''pro-life'', the movement aims to hegemonize its ideology and its image, and thus to normalize itself in society. This lets them gain more impact because whenever one meaning is dominant, it also becomes powerful as it is not questioned. Since the renaming, the pro-life movement has been anything but quiescent. In fact, it has done a skillful job at convincing people to side with them. This, among other things, has led to new restrictions on abortion rights; the 'Texas Heartbeat Act' being one of them. In the subsequent section, we will go in-depth on this matter.

The Texas Heartbeat Act

In the USA, the Roe case has recently become relevant again. Since 2011 attacks on Roe vs Wade have been rising; anti-abortion politicians have been gaining political power. This has led to multiple nationwide challenges to safe and legal abortions. In 2019 alone, states adopted more than 37 new restrictions on abortion rights and access. Moreover, the state legislative season of 2021 has been declared the most hostile in recent history for reproductive rights and health (Planned Parenthood, n.d.-c).

As a result of the introduction of bills such as the Heartbeat Act in Texas, the female reproductive movement that has existed for roughly fifty years has become more active than ever.

As recently as September 2021, an anti-abortion bill has come into effect in the state of Texas; the so-called ‘Texas Heartbeat Act,’ which according to Texas Governor Greg Abbott protects ‘every unborn child with a heartbeat’ (Olohan, 2021). This bill falls into the category of 6-week bans (Planned Parenthood, n.d.). Abortions are banned after 6 weeks of pregnancy, which is when the fetus’ heartbeat can be detected. Exceptions are made only for medical emergencies, but not for cases of sexual assault or incest. What is more, the law allows people to sue abortion clinics in Texas or even individuals who help pregnant people obtain abortions (Olohan, 2021). The problem with bills like these is that people often only find out that they are pregnant after the six weeks have already passed, making it impossible to get an abortion within that time span.

As a result of the introduction of bills such as the Heartbeat Act in Texas, the female reproductive movement that has existed for roughly fifty years has become more active than ever. This time around, the movement shows up both offline and online, mostly under the name of Pro-Choice or My Body My Choice, both of which have become popular hashtags. To read more about the 21st-century manifestations of the Pro-Choice movement and its counterparty, the Pro-life movement, click here and here.

References

Abbott, K. (2012, November 27). Madame Restell: The abortionist of fifth avenue. Smithsonian Magazine.

Assendelft, L. V., Schultz, J. D., & Assendelft, V. L. (1998). Encyclopedia of Women in American Politics (1st ed.). Greenwood.

Becker, H. (1963). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. The Free Press.

Diggit Magazine. (n.d.-a). Hegemony.

Diggit Magazine. (n.d.-b). Ideology.

Foucault, M. (2010). The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978--1979 (Lectures at the College de France) (First ed.). Picador.

Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional vision. American Anthropologist, 96(3), 606–633.

History.com Editors. (2018, March 27). Roe v. Wade. HISTORY.

Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Roe v. Wade (1973). LII / Legal Information Institute.

Luker, K. (1985). Abortion & the politics of motherhood (1st ed.). University of California Press.

Maly, I. (2016). ‘Scientific’ nationalism: N-VA and the discursive battle for the flemish nation. Nations and Nationalism, 22(2), 266–286

Mohr, J. C. (1979). Abortion in America: The origins and evolution of national policy (galaxy books). Oxford University Press.

Olohan, M. M. (2021, May 19). Texas passes abortion ban protecting ‘Every unborn child with a heartbeat’. The Daily Signal.

Planned Parenthood. (n.d.-a). Bans on abortion at 6 weeks. Planned Parenthood Action Fund.

Planned Parenthood. (n.d.-b). Roe v. Wade: The constitutional right to access safe, legal abortion. Planned Parenthood Action Fund.

Planned Parenthood. (n.d.-c). Timeline of attacks on abortion. Planned Parenthood Action Fund.

Planned Parenthood. (2014). Roe v. Wade: Its history and impact.

Reagan, L. J. (1997). When abortion was a crime : Women, medicine, and law in the united states, 1867-1973. University of California Press.

Weingarten, K. (2014). Abortion in the american imagination : Before life and choice, 1880-1940. Rutgers University Press.