The Proud Boys in the hybrid media system

The Proud Boys are a far-right group founded in 2016. Although their main place of operation is the United States, the group has a transnational reach. In this article, I will be analysing how this group makes use of the hybrid media system to spread their ideology, makes use of metapolitics, and organises offline action. This analysis will be fueled by data collected from the Proud Boys website, their Telegram message stream, and their Parler page.

Who are the Proud Boys?

The Proud Boys are a networked organization that was founded by Gavin Mcinnes during the 2016 presidential elections in the United States. Only men can become members of the Proud Boys. In order to become a Proud Boy, “a man [must] declare he is “a Western chauvinist who refuses to apologize for creating the modern world”, as stated on the Proud Boys website (“Tenets", 2020).

Proud Boys can be recognized by specific attire, namely a black polo with yellow details produced by the brand Fred Perry, which has since discontinued the sale of these shirts. The logo of this company, a wreath, is also a prominent Proud Boys symbol, appearing on clothes and in online activity. This attire is often accompanied by red Make America Great Again hats, items including the flag of the United States, as well as gear associated with the military, such as camouflage print.

Though the group was founded in the United States, and the majority of their nationalist posts seem to be focused on the United States, the online network extends all over the world, with the possibility of joining local organizations or ‘chapters’.

The organization gained renewed attention when it was mentioned in the first 2020 presidential debate. President Trump was asked to condemn white supremacists and far-right groups, and Joe Biden prompted him to specifically address the Proud Boys. In response to this, President Trump told the group to 'stand back and stand by' (Trump, 2020). This mention sparked expressions of excitement among Proud Boys, and Google searches for the term 'Proud Boys' spiked. 'His' Proud Boys were also massively present during the January 2021 Capitol riots.

Proud Boys Trumpism

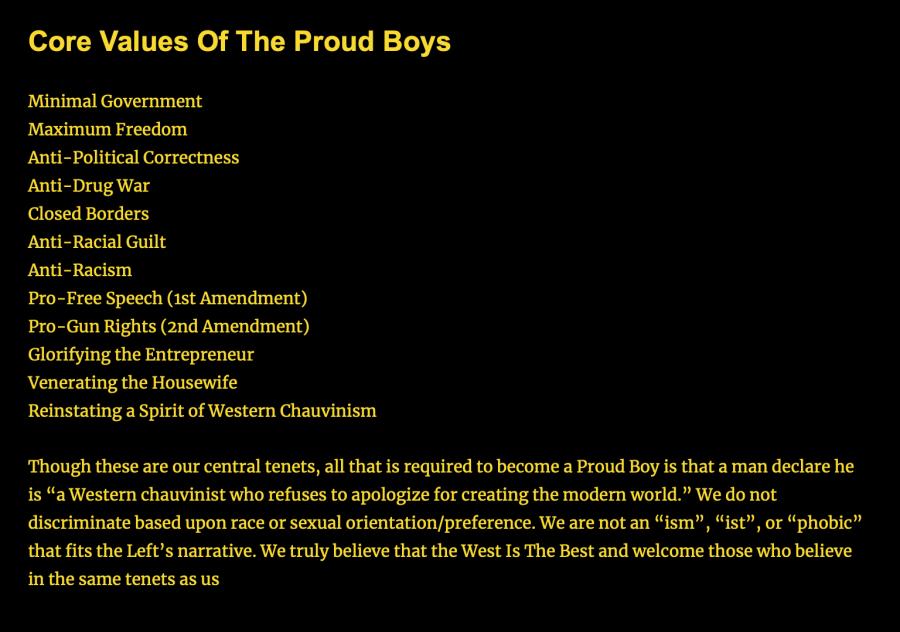

What binds the Proud Boys together as a group is their shared Ideology. The Proud Boys define their ideology with a straight-forward list of core values on their website. This list includes values such as ‘maximum freedom’, ‘closed borders’, ‘anti-racism’ and ‘pro-gun rights’. Their website banner states “Proud Boys, Western Chauvinists”. (“Tenets", 2020).

Core values of the Proud Boys as stated on their website.

However, this static list far from covers all aspects of their ideology. Furthermore, these keywords deserve detailed analysis that highlights their metapolitical goal (Maly, 2019). What truly defines their ideology is not a list of keywords, but rather how these keywords are defined and what ideological values are displayed in their behaviour and discourses.

The central force in the Proud Boys' ideology is anti-Enlightenment nationalism (Sternhell, 2010; Maly, 2018). The foundations of the group were laid with the presidential election of Donald Trump. Trumpism - or neoliberal nationalism - remains the core ideology of the Proud Boys. They see American culture and values as under attack from external forces such as immigration and non-traditional gender identities. The left is blamed for these forces, and hence the Proud Boys are very vocally anti-left, as well as anti-Antifa and anti-BLM. These groups are constructed as dangerous and as posing a threat to the nation's culture, which the Proud Boys believe to be superior.

This nationalism is intertwined with neoliberalist ideology: they celebrate non-intervention in the economy, free trade and enterpreneurship. This neoliberal resistance against state intervention is also visible in how the Proud Boys talk about the coronavirus: they are anti-mask and anti-vaccine. Wearing a mask or getting a vaccine, as imposed by the state, goes against the freedom that they value.

In all this, the Proud Boys hold a prominent place for the normalization and celebration of violence. Their initiation ritual requires new members get into a fight 'for the cause' - anything that conflicts with the Proud Boys' ideology is fair game. But before we can dig deeper into who the Proud Boys are, it is important to understand the role of media in their rise to prominence.

The Proud Boys' platforms

Due to the rise of digital media, our media system is going through a transition where old (broadcast) media logics are combined with new (digital) media logics. This system offers any user the opportunity to "shape and disrupt information flows that were traditionally controlled by broadcast media" (Chadwick et al., 2015). The Proud Boys use this hybrid media system in two ways: for the production of what Maly (2019) describes as metapolitics 2.0, and to choreograph online action.

In 2018, various verified accounts owned by the Proud Boys were suspended by Twitter for violating a policy against “violent extremist groups.”

One thing that’s immediately noticeable about the Proud Boys' media strategies is their lack of presence on mainstream social media platforms such as Facebook or Twitter. This is a direct result of both Facebook and Twitter's policies: in 2018, various verified accounts owned by the Proud Boys were suspended by Twitter for violating a policy against “violent extremist groups.” Later in the year, Facebook followed this example by also banning various Facebook and Instagram pages belonging to the group under a policy against hate organizations and figures.

The Proud Boys switched to alternative platforms such as Telegram and Parler (which is now also being de-platformed). Actors in the hybrid media system have to make choices about what platforms best fit their goals (Chadwick et al., 2015). The Proud Boys recognised that they could not post on Twitter and Facebook in the way they wanted to and were therefore forced to move platforms.

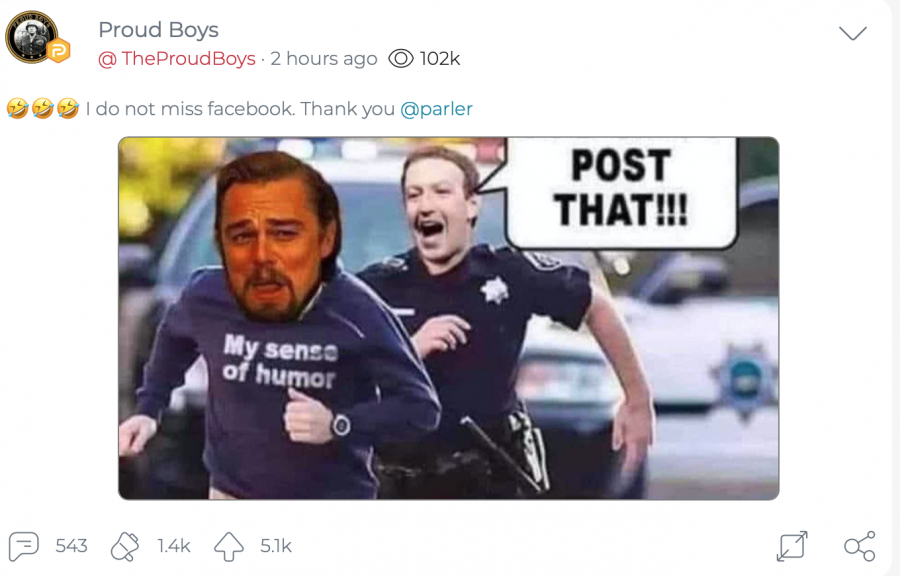

Proud Boys frame more mainstream media as part of the 'deep state' (a conspiracy theory that there is a hidden government within the US government) and as being anti-Proud Boys. As a result, they educate their audience about those media (Maly, 2021) by frequently making fun of Facebook and Twitter in their memes.

Facebook being used as the subject of a meme in a Parler post.

Moreover, they are successful in their use of these platforms: the Telegram feed has over 9000 subscribers, but since this feed is shown on the website it's likely that many more look at this feed. In October 2020, most posts on the Telegram feed have around 4K views, with some posts getting even around 7K views.

Even bigger, their Parler page has 187K followers (December 2020). Messages on these posts get thousands of upvotes and 'echoes' (Parler shares) as well as hundreds of comments. The deplatforming from Twitter didn't mean the end of the Proud Boys. They did not lose much in terms of numbers - their Twitter page only had about 36K followers before it was suspended in 2018.

Mainstream media coverage, as well as Donald Trump's mention of them, unintentionally amplified the Proud Boys' reach and recruitment.

Numbers are not the only things that matter on these platforms: the loss of their Facebook account meant a loss of power on one of their main recruitment platforms. Facebook and Twitter are used by a wide array of users - not everyone will find their way to alternative platforms, posing difficulties for recruitment and further growth. However, part of this recruitment is (unintentionally) done by mainstream media coverage as well as Donald Trump's acknowledgement of them. This coverage gives them more exposure to potential members.

Their reach on alternative digital media shows their knowledge of media logics or what Maly calls algorithmic knowledge. This knowledge also shows in how they structure posts with the goal of generating engagement. Many of their posts follow a script of "share if... / like if.../react if ..." followed by a stance that they know their follower base agrees with.

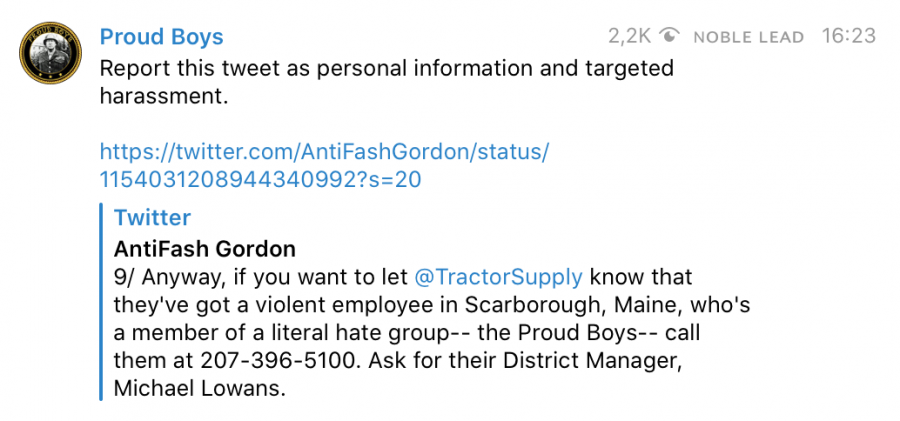

An example can be found in posts such as 'Echo if you're ready for four more years of Trump' (@TheProudBoys on Parler, 2020). The Proud Boys know their members are pro-Trump, and therefore know posts like this one will generate lots of engagement. This engagement also takes the form of calls to action, often in the form of asking members to report certain accounts or posts.

The Proud Boys using Telegram to request their members to report a certain tweet.

They haven't completely left platforms such as Twitter and Facebook behind: since these are big platforms that can be seen as producing important discourse, the Proud Boys mark their presence on these mainstream platforms with mass shaming and reporting actions .

As the Proud Boys are very active on their preferred platforms, their ideology is in a constant process of (re)production through texts, images, memes, videos. The Proud Boys use their platforms to construct an ideological message, with digital media as a central force, in what Maly (2019) calls new right metapolitics 2.0. With the usage of memes, pictures, videos, mass reports, and much more daily digital content, the Proud Boys' metapolitical strategy is embedded into internet culture.

The usage of a meme to convey meanings of anti-Twitter, anti-BLM, and anti-Biden/Harris campaign.

This multimodal discourse production reflects the change in new right metapolitical battles (Maly, 2020): it's no longer just the intellectuals that produce metapolitical discourse, but also other parties such as activists, politicians, prosumers, and in this case users on the Proud Boys Parler.

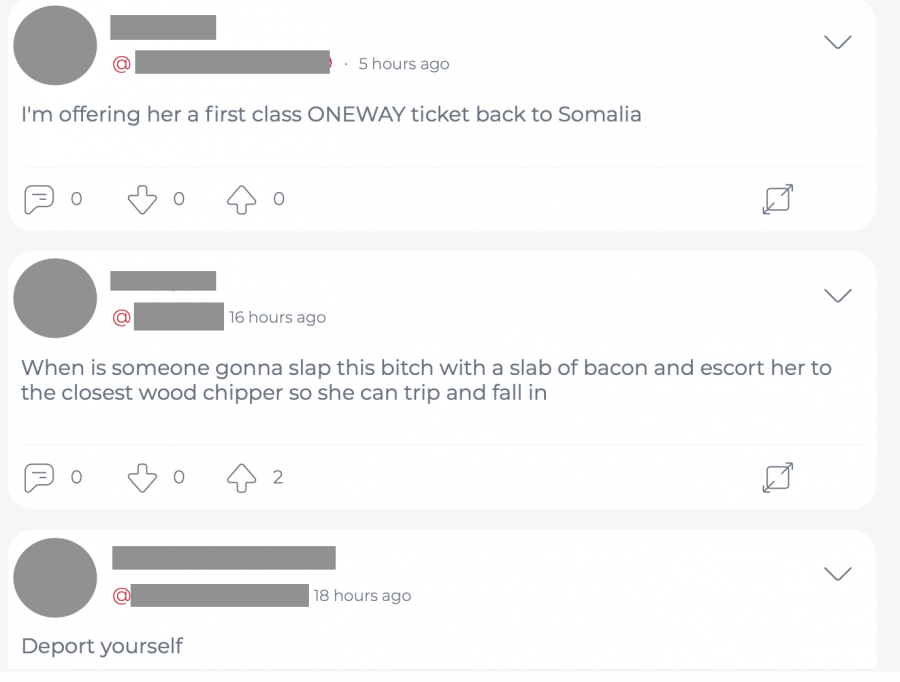

Scrolling through their channels immediately reveals how posts on their platforms are used to convey their ideology: plenty of posts cover anti-Antifa, anti-BLM, anti-mainstream media, and pro-Trump stances. Although their website states that "we are not an “ism”, “ist”, or “phobic” that fits the left’s narrative", many posts, comments, and speeches by prominent figures can be classified as such.

For example, in a Parler post about Ilhan Omar's remarks comparing Trump campaign rallies to 'klan rallies', the majority of the comments mention deportations or other racist themes. Further it does not take long to find jokes about gay or trans people, or misogynistic comments either. The Proud Boys may not be willing to adopt 'these imposed 'ism', 'ist', or 'phobic's", but they are advocating for them. They reframe their racism as free speech. Actions like these show that no matter how they describe their values, their behaviour is what truly makes their ideology visible.

Comments on the post on Ilhan Omar, on Parlor.

All their online activity enables the Proud Boys to shape their movement in order to appeal to a broader audience, with the metapolitical goal of hegemonizing new-right ideology. This usage of metapolitics requires knowledge of media logics in order to effectively reach the intended audience. The Proud Boys have shown their digital literacy is effective for metapolitics as proven by their ever-growing platforms where each post can easily amass thousands of engagements with it.

Offline gathering

The first steps in organizing offline actions are found in how the Proud Boys use the hybrid media system for the production and distribution of metapolitics. But they also use this system to explicitly organize offline gathering. Though most media coverage of the Proud Boys focuses on their presence at rallies or (counter-)protests, local chapters also gather offline on a regular basis. This process of offline assembly is described by Gerbaudo (2012) as the choreography of assembly: the use of social media to choreograph offline action. The networks, in this case, Parler and Telegram, play various roles in this process of choreographing online action.

First and foremost, the networks are used for the practical part of organising: to share the date, time, and place the Proud Boys are supposed to show up. But more importantly, the networks have an important function in creating the shared identity needed to trigger people to do something, in this case, show up to a rally or protest (Gerbaudo, 2012). The Proud Boys create a shared feeling of urgency through numerous posts about the dangers of Antifa or the BLM movement, encouraging their members to show up.

An example of this choreography of assembly can be found in the Proud Boys' rally on September 26th in Portland.

Announcement of a Proud Boy rally to 'end domestic terrorism'

Announcements of assembly like this one include multiple elements that make use of this shared identity. 'End domestic terrorism' refers to Donald Trump's labeling of Antifa activists, particularly those active in Portland, as domestic terrorists. 'Free Kyle Rittenhouse' refers to the man who killed two people at protests in Kenosha - the Proud Boys regard him as a hero. The third element, 'do it for Jay,' refers to Aaron J. Danielson, who was shot in Portland after clashing with protesters. Additionally there are the visual elements: the colour combination of black and yellow is a known Proud Boy symbol, and so is the yellow wreath.

A shared identity is created by recognition of symbols and meanings.

These elements all play on established Proud Boy stances. Because the Proud Boys share these ideas, values and identities, an urgency to show up is created. In this way, their online presence functions as a vehicle for their offline assembly though this identity establishing function. The way in which Proud Boys are able to recognise these meanings, symbols and colour combinations adds to the feeling of shared identity. Moreover, with regular offline gatherings of local chapters, these groups are not just based on their strong shared identity, but also on the strong bond between members.

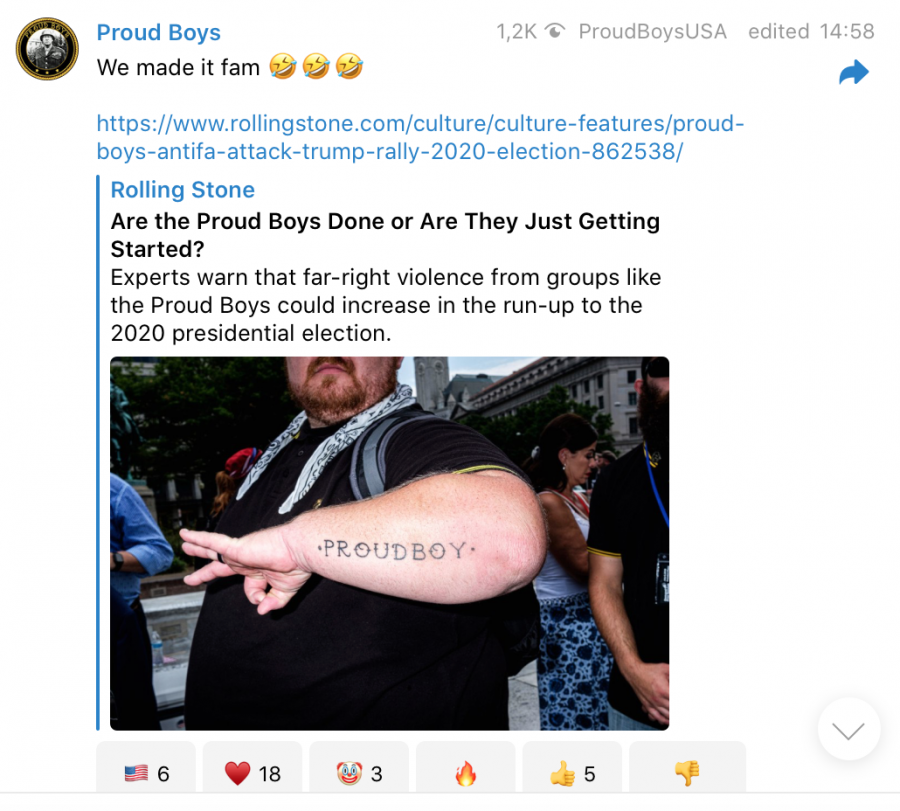

The Proud Boys' offline assemblies oftentimes gain attention from mass media, especially when violence occurs. Just like in this message, the Proud Boys can respond to this coverage in mass media through their own channels. This shows how different components in the hybrid media system intertwine with cross-platform interactions, and how offline assemblies connect back to online discussion.

The Proud Boys responding to (negative) media coverage.

The Proud Boys in the hybrid media system

The Proud Boys have proven themselves competent in exploiting affordances, algorithms and media logics to gain visibility in the hybrid media system. They use specific alternative platforms within this system in order to shape their own coverage. On these platforms, they are very successful in generating plenty of engagement with their posts.

Metapolitical strategies are used to constantly (re)produce their ideological ideas in various modalities such as text, images and memes, with digital media logics as a central force. In their behaviour, it's visible how their use of metapolitics aligns with the goal of hegemonizing new-right ideologies, with the central forces of nationalism, traditional gender identities and the celebration of violence. The hybrid media system is used to create bonds between the members as well as (re)produce shared meanings and identity.

While this paper focuses on the Proud Boys' online presence, they operate in an online-offline nexus, where their usage of the hybrid media system holds an irreplaceable function in their offline practices, and their offline practices feed back into their online practices. This online-offline nexus is visible in all their practices, for example in the January 2021 Capitol riots, where many Proud Boys were present after being encouraged and organised by online activity.

By creating and reproducing shared meanings online, a shared Proud Boys identity is in constant reproduction. The Proud Boys have created a specific use of the hybrid media system that works with their goals and creates a powerful communication network. It is this communication network that organized offline action at the Capitol. In this way, the Proud Boys in the hybrid media system played an irreplaceable role in the Proud Boys presence at the Capitol riots.

References

Chadwick, A., Dennis, J., & Smith, A. P. (2015). Politics in the age of hybrid media: Power, systems, and media logics. In The Routledge companion to social media and politics (pp. 7-22). Routledge.

Gerbaudo, P. (2012). Tweets and the Streets: Social Media and Contemporary Activism. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ideology. (2020). Retrieved 18 November 2020.

Maly, I. (2018). Nieuw Rechts. Epo.

Maly, I. (2019). New right metapolitics and the algorithmic activism of Schild & Vrienden. Social Media+ Society, 5(2), 2056305119856700.

Maly, I. (2020). Metapolitical New Right Influencers: The Case of Brittany Pettibone. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9(7), 113.

Maly, I. (2021). Ideology and algorithms. Ideology, theory and practice.

Proud Boys [@TheProudBoys] (n.d) posts [Parler Page].

Proud Boys [@ProudBoysUSA] (n.d) posts [Telegram Chat].

Sternhell, Z. (2010). The anti-Enlightenment tradition. Yale University Press.