Stereotypes and sexism in the aviation industry

Stereotypes and sexism are still very common in the Aviation industry. Less than 5% of all airline CEOs are women (Shankman, 2015). While more companies are gradually focusing on gender equality and a balanced workforce, the airline industry lags behind and gender stereotypes and sexism persist.

In the aviation industry, the glass ceiling seems higher than in any other industry, with only 18 female CEOs in 365 commercial airlines in 2015 and there are few signs of improvement. This paper focuses on female stereotypes in the aviation industry; on sexism in aviation and also looks at possible initiatives to decrease these stereotypes and increase gender equality in the aviation industry.

Stereotypes, sexism and gender roles

The perception of the airline industry being a masculine business stays in place via stereotypes. Mainstream media and society itself project stereotypes onto children. Around the age of four, children start becoming aware of their gender roles through the toys they can play with. Boys can play with boy's toys, such as cars and airplanes and girls can play with Barbie dolls, or with miniature cooking kits for example. This phenomenon is called gender socialization: these are generally shared rules and expectations regarding people’s behavior according to ‘their gender’.

When growing older, these stereotypes and gender norms are again confirmed. The generalized and oversimplified representation of stereotypes reflects preconceived attitudes about people. In this case, based on their gender. As a result, when children think about their role models, boys see pilots as role models, while for girls their role model is usually the flight attendant.

“Of course, Qatar Airways has to be led by a man, because it is a very challenging position. ''- Akbar Al Baker, CEO Qatar Airways

Stereotypes also create problems for women's careers, as they seem 'unable to fit in'. When recruiting for positions, people often search for people that ‘fit in’. Skills and talents are not directly looked at. Instead, the features that someone should have in order to ‘fit in with the standard’ are usually the most important factor. This makes the notion of women being flight attendants and men being pilots problematic. However, this is even more visible in the management layers of organizations. For male gender-typed positions, which include top management positions, women have a strong disadvantage when applying. This is because they are not perceived as 'fitting in' (Gaucher, Friesen & Kay, 2011).

Nowadays, ‘soft skills’ such as interpersonal sensitivity and the ability to develop new talents are becoming increasingly important for organizations, but for someone to be successful in top management positions, one should still have the achievement-oriented aggressiveness and emotional toughness associated with men. These 'skills' are therefore contrary to the descriptive stereotype of women, which again results in women not 'fitting in'. The general notion seems to be: ‘’think manager, think male’’.

Women are still seen as ‘different’ and should adapt to the existing corporate culture in order to be able to fit in.

Very recently Akbar Al Baker, a newly appointed member of the board of Governors of the International Air Transport Association (IATA), who is also the CEO of Qatar Airways, was asked what should be done to tackle the lack of women in Middle Eastern aviation. He answered: “Of course, Qatar Airways has to be led by a man, because it is a very challenging position.” This idea does not only put emphasis on female stereotypes, but also made women believe that they are not suitable for the job. This in turn makes them believe the prescriptive stereotypes surrounding what is correct behavior for women and what they can and cannot do.

As a result, women feel that the skills and talents they have are not suitable for handling 'typically' male positions, which profoundly affects their performance (Heilman, 2001). This has as a consequence that men cluster at the top level of the organization and women stay at the lower layer. This is called vertical segregation. However, it also leads to horizontal segregation, where men get assigned different tasks than women, based on their gender and gender stereotypes, even though they are active on the same occupational level.

A view to the top?

Stereotyping also leads to sexualization.This is something the media have played a significant role in as well. In 1971, the slogan of an American airline company called The National Airlines was ‘’I am Cheryl. Fly Me’’. Flight attendants became sexualized; their uniforms included mini skirts, and they could not be married or have children, as they should be ‘available’ for the male passengers. Most airlines had the motto: Sex sells. This turned into a culture in which all flight attendants were female and had to serve the masculine society. All other jobs in aviation were reserved for men (Seibel, 2018).

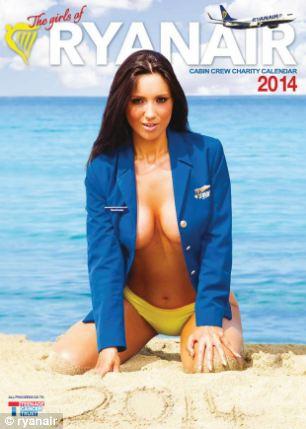

Unfortunately, this patriarchal culture persists to this day. In 2008, Ryanair launched a Calendar to raise money for charity that featured flight attendants portrayed in a sexually suggestive manner, wearing nothing more than bathing suits. This advertisement highly objectifies and sexualizes women. As a result, individuals start to feel that their sexuality and body are their main 'skill' and that is what they should use in order to be successful.

Calendar Ryanair

Another example of how this gender role stigma is kept alive is the movie View to the Top, which was released in 2003. The movie is about ‘A small-town girl who does everything to achieve her goals’. The subtitle of the movie reads: ‘‘do not stop till you reach the top''. However, in the movie, working on intercontinental flights as a flight attendant is the absolute top, instead of being a pilot or having a management position in the same industry. This contributes to the stereotype of women in the aviation industry being flight attendants instead of working in other positions as well. As a result, women and girls do not consider other jobs in the aviation industry. A British pilot explained to the Telegraph that she educates children in primary schools on career possibilities, and that many girls did not even know that it was possible for them to become pilots (Morris, 2015).

Less than 4% of all non-pilot aviation workers are female (Ison, 2011).

The numbers show that this is not a problem exclusive to pilots. The representation of women also falls short for other jobs in the aviation industry. David C. Ison (2007) has researched the future of women in the aviation industry. He found that the participation rate of women in higher aviation education in 2007 was 11,5%. Higher aviation education does not just include studying to beome a pilot, but also aviation or airport management studies. Unfortunately, not all graduates feel like pursuing a career in the industry they obtained a degree in, and less than 4% of all non-pilot aviation workers are female (Ison, 2010).

It’s a men’s world

But why obtain a degree in aviation and not pursue a career in that industry? The masculine character of the industry makes it difficult for women to find jobs or to get promotions in the long run. Assumptions and prejudices about women quitting after having children, career aspirations and even the flying abilities of women make it difficult for them to find jobs, but also result in an unpleasant work environment in which women are not treated equally. This affects women's working lives and the relationship they have with male coworkers. Women are expected to adapt to the masculine social system of aviation, rather than the business changing and becoming more welcoming towards women. Currently, women are still seen as ‘different’ and they should adapt to the existing corporate culture in order to be able to fit in (Neal-Smith, Cockburn, 2009).

Meanwhile, companies claim to be gender-neutral and not favoring men over women. The long-hours culture, however, has a negative effect on women in management positions in all industries, as women still take primary responsibility for childcare and managing the household. This means that the burden of long working hours affects women more significantly, as they carry the responsibility of domestic activities alongside their career. For women to be able to fill (top) management positions, they should refrain from being responsible for unpaid work, such as household and other domestic activities. In other words, in order for women to fill the above-mentioned positions in current society, they have no choice but to adapt to the masculine corporate cultures (Rutherford, 2011).

View to the actual top

To encourage women to pursue a career in the aviation industry, airline businesses should become aware of the need for a diverse workforce, and what's even more desirable, should take action to reach gender equality in the industry. Airlines are complex companies with distinct segments, varying from operation to finance to engineering. Therefore, executives should have experience in multiple areas in order to be able to carry out the job. For this reason, airlines should focus on creating a pipeline with female talent and give these talents the opportunity to gain experience in multiple segments of the organization. Management should take initiatives on getting women out of their comfort zone and encourage them to grow in the organization.

Besides, the numbers on women in aviation should become more transparent. When a reporter from a large travel platform asked the board of IATA about the percentage of female CEOs in the aviation industry and how gender disportion effected the industry, the association failed to give a clear answer, even though they represent 82% of all airlines (Shankman, 2015). IATA itself is far from a good example, as it has a board of governors consisting of 31 members, of which only one is a woman. It is time for the association to lead by example, have a more diverse board, take action to create transparency and educate airlines on creating a pipeline with female talent.

Luckily the industry is waking up and realizes that diversity is a key element in having a healthy and profitable business.

Luckily the industry is waking up and realizes that diversity is a key element in having a healthy and profitable business. In recent years, associations dedicated to female aviation professionals have been created. One example is the Women in Corporate Aviation Association, which has been founded in order to become mentors and role models for next generations.

Associations like this help to break down stereotypes and to increase the visibility of women in aviation, which in return will result in an increase of female aviation professionals as role models for girls. But for the aviation industry to attract, promote and retain female talent, the industry must change its corporate culture first and must get rid of the masculine identity it has. Even though (social) media are a transmitter of stereotypes and gender norms, they can also be used as a platform to challenge these stereotypes. It is time for both the media and the aviation industry to break down stereotypes and refrain from the masculine corporate culture in organizations in order to get female talent to the top and finally break through the glass ceiling.

References

Capa. (2015) Why don't women run airlines?

Gaucher, D., Friesen, J., & Kay, A. C. (2011). Evidence that gendered wording in job advertisements exists and sustains gender inequality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 109–128.

Heilman, M. E. (2001). Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 657–674.

Ison, D. (2010) The Future of Women in Aviation: Trends in Participation in Postsecondary Aviation Education. Vol 19, No. 3 (spring, 2010). p35-36.

Neal-Smith, S. Cockburn, T (2009). Cultural sexism in the UK Airline Industry. Gender in Management: An international Journal, Vol. 24 Issues:1 pp.32-45.

Morris, H. (2015) Why are there so few female pilots?

Rutherford S. (2011) Are You Going Home Already? The Long-Hours Culture. In: Women’s Work, Men’s Cultures. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Seibel, B. (2018) Sexy stewardesses were exploited by airlines.

Shankman, S. (2014) Woman Account for fewer than 5% of Airline CEOs around the world.

Topham,G., Kollewe, J. (2018) Qatar Airways chief says only a man could do his job.