Street protests and the creative spectacle

How social media’s sharing culture is influencing the way people voice their message through street protest signs

Parts of the US economy may already be experiencing a Trump Slump, but one area which has seen a significant boost from the new president is large-scale street protest. In the first weeks of his administration there were protests almost every day, both in the US and abroad. What with this and other prominent issues such as Brexit, mass public demonstrations appear to be as popular today as during any time in recent history.

Street protests work as a form of spectacle on many levels. The symbolism of occupying the public space, of disrupting the everyday flow of the economy, the literal and metaphoric value of congregating en masse to express the mood of the people – all these are elements in the meanings that the act of demonstrating generates.

In the context of visual representation, size matters. The larger the spectacle, the more potent the underlying meaning about public mood.

There’s long been an important relationship between protests and the media. Back in 1866, for example, when the Reform League were campaigning for male suffrage in the UK and held a huge demonstration in Hyde Park, it was the way this was reported by the papers that led to the large increase in support for their movement.

Since the rise of visual-representational media (photography, television), protests have arguably had an even stronger dual existence, taking place in a particular time and space while also being relayed to a dispersed audience. And this has had an influence on how they operate as meaningful interventions. To put it crudely, in the context of visual representation, size matters. The larger the spectacle, the more potent the underlying meaning about public mood.

As was seen in the ruckus about the size of the crowd at Trump’s inauguration and the juxtaposition of this with the women’s march the following day, this tenet still holds true today, despite the new and complex media environment we now live in.

But alongside this there’s been a change in the look of protests over the last few years, influenced specifically by social media and mobile technology. As Nick Asbury writes in the Creative Review, ‘protest has taken on a performative aspect in recent years – it’s as much about the tweeted picture as it is about the protest. And the placard is the focal point – probably the most shared aspect of any demonstration’.

What has happened, in other words, is that attracting the gaze of the media is not now solely about large-scale spectacle. Equally effective in an environment where everyone has their own recording- and publishing-device are small but striking acts of self-expression. And this has resulted in a shift from standardised placards handed out by organisations to homemade signs, often with brief, witty slogans, which become a central device in the way the message of the protest is spread.

This is not to suggest that the individual, hand-crafted placard is anything new. There are plenty of examples of these from the counter-culture protests of the 1960s, for example. But what is new is the speed at which their messages are circulated.

Gone are the days when it might take months of planning to bring large crowds of people onto the streets.

Another factor in what might better be regarded as a return rather than a shift to the personalised placard is the effect social media has had on the ability for protests to be organised at speed. Gone are the days when it might take months of planning to bring large crowds of people onto the streets. When demonstrations are called at only 24-hours’ notice, it’s beyond all but the most resourceful of organisations to have mass-produced placards printed and ready for distribution. This makes the individually-produced placard almost inevitable. Add to this an increasing disenchantment with organised politics and the rise of single-issue campaigning and it’s easy to understand why the personally significant expresses itself through the personally signified.

Central to these homemade signs is the use of creativity as a way of attracting attention. And here the influence of social media works in two distinct ways. Not only does it encourage a format which is suited to a sharing culture, but it also supplies an archetype for that format in the shape of meme culture. In other words, signs today are often designed specifically to be picked up and circulated on social media, and this is reflected in their content in terms of both style (i.e. brief and epigrammatic) and use of a shared set of cultural reference points.

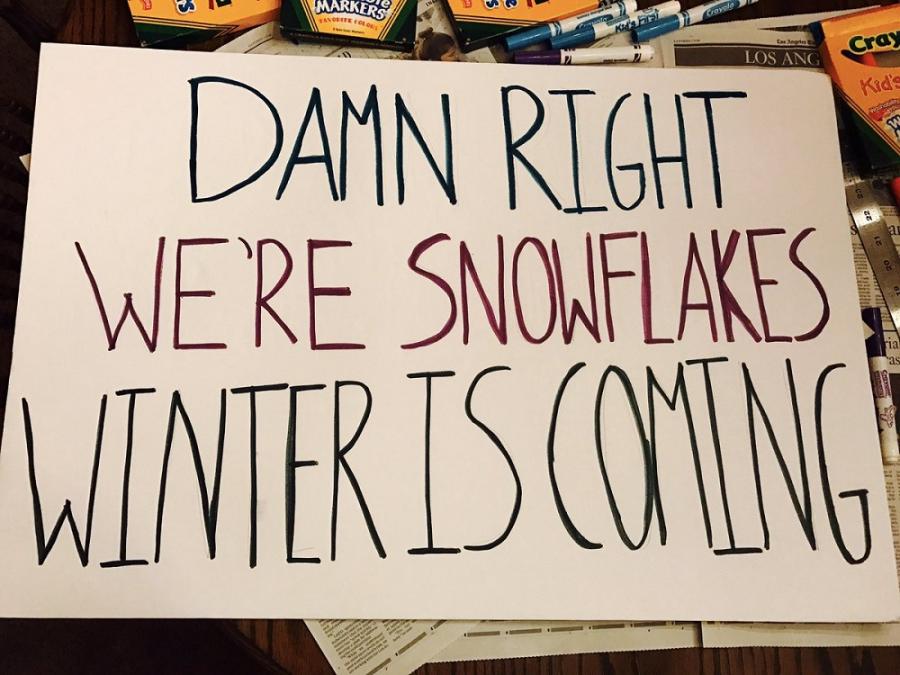

Take for example a sign such as ‘Damn right we’re snowflakes. Winter is coming’. This has a highly context-based meaning, recontextualising and appropriating two distinct pop culture references. Unless you recognise these references, the meaning remains obscure; but if you do recognise them, their use indicates an alignment, and thus solidarity, with a particular community.

For those unfamiliar with them, the references operate as follows. The phrase ‘winter is coming’ is the motto of House Stark in George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire and the HBO series Game of Thrones. It’s used in the drama as a warning that difficult times are on their way, and has been widely adapted into various memes, most of which ironically predict the oncoming of some trend or collective behaviour.

The term ‘snowflake’, meanwhile, has come to be used to refer to people, particularly on the left and usually millennials, who are considered to be overly-sensitive about aspects of modern social interaction. It derives from the chastisement ‘You are not special. You are not a beautiful and unique snowflake’ in Chuck Palahniuk’s novel, Fight Club – the idea being that Generation Y have been brought up in an overly-protective environment which has made them unsuited to the trials of everyday adult life. The term has since broadened its meaning, so that, for example, the pro-Brexit politician Michael Gove can use it to complain about anyone who criticises his view of the world. But by being combined with the admonition from Game of Thrones, its meaning is re-appropriated by those it originally targeted, and is turned from a sign of fragility to one of communal strength.

A similar process is at work in the sign ‘This is my resisting bitch face’. Here again, the meaning relies on an intertextual knowledge of meme culture, in this case the ‘Resting Bitch Face’ meme. This became popular at the end of the last decade to refer to a sullen or contemptuous expression that some people (mostly women) supposedly adopt unconsciously. The element of sexism in the way the phrase is usually applied is challenged in the street protest slogan which re-appropriates its use (along with the word ‘bitch’) and explicitly politicises it by replacing 'resting' with 'resisting', turning it into a positive statement of defiance.

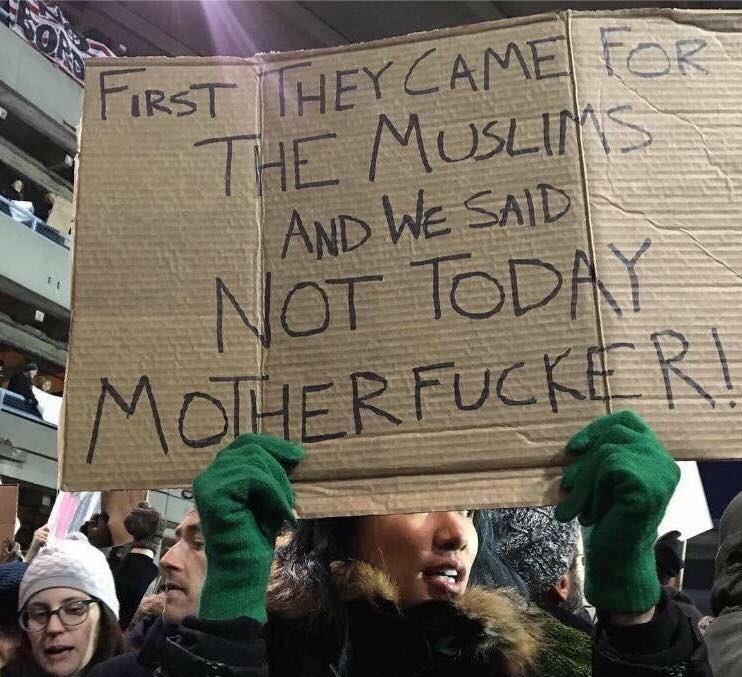

Not all signs have their roots in contemporary culture, of course. The popular ‘First They Came For the Muslims And We Said Not Today Motherfuckers’, for instance, is based around a phrase from Martin Niemöller’s famous verse from the 40s about political solidarity: ‘Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out – Because I was not a Jew / Then they came for me – and there was no one left to speak for me’. But whereas Niemöller’s parable warns against the dangers of apathy, this is subverted in the slogan, which again offers a very explicit statement of defiance.

Along with the intertextuality involved in the creation of these signs, there’s a transmedia aspect to their circulation. Before a protest, Twitter accounts and online sites offer advice and ideas about designing such slogans. The results are then recorded during the march and shared online, with some signs including hashtags to facilitate the sharing process and allow people to follow the movement online. This parallels a very old function of trade union banners, which were used to further the reach of the message when the noise of protest meant speakers at the event might not be heard.

Photographed images of signs are then in turn compiled into articles by newspapers, which document both their use during marches, and the way they can have an afterlife by, for example, being made into make-shift shrines once discarded. The images also subsequently become archived online, while museums, such as London’s Bishopsgate Institute, collect together examples of the material resources themselves as part of the history of the capital.

The process, then, is one of close choreography between traditional and new forms of communications technology, with social media giving new significance and impact to the simple historical archetype of the written sign. And the role played by everyday linguistic creativity in this is crucial, acting as a catalyst for the spread of a message of global defiance.