Thierry Baudet as a Hybrid Media Star

In 2016 a new name entered the Dutch political field: Thierry Baudet. A year later, during the elections, the right-winged politician got two seats in the Dutch parliament. His party FvD (Forum voor Democratie) spent a lot of money on online advertising, and Baudet himself is not averse to media attention. He uses Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter to spread his opinions and to gain followers, and thereby he steers the information flows. What is Thierry Baudet's role, in the Dutch hybrid media system?

Who is Thierry Baudet?

Thierry Baudet is famous in the Netherlands for having anti-EU, anti-Euro, and anti-immigration statements. Baudet’s right-wing party FvD started in 2014 as a think tank, but in 2016 it gained success in the Dutch elections for the House of Representatives. As a party leader, he has a seat in the Dutch House of Representatives, together with his companion Theo Hiddema, who left the party in November 2020. Before all that, Baudet studied law at Leiden University where he graduated in 2012 with ‘The Attack on the Nationstate’, in which he talks about the dangers of supranational institutions such as the European Union. He advocates direct democracy and would like to introduce binding referendums (Boersema, 2019).

Baudet has been frequently in the media for having striking statements and is skilled at connecting with his audience through social media. His opening statement in the House of Representatives was in Latin, he wore a bomb vest once during a debate and he likes to create an image of himself as an intellectual. There even is a blog which has collected quotes from Baudet such as: “When a woman says "no," don't think, "Oh, she doesn't want it," then you should say, "Honey, we're going to have a drink." Just insist” (DWDD, 2014).

Forum voor Democratie (FvD) gained many voters in 2016 because of advertising via Facebook. As mentioned on Brandpunt+, FvD paid Facebook for each member introduced, thereby violating Dutch privacy legislation (Snelderwaard & Van den Berg, 2020). In the same article, we can read how FvD targeted their audience via Facebook. Since Baudet clearly has a lot of media attention, what is his role in the current Dutch media system?

Campaigns are now a new way of gaining (political) power

Let's first have a look at how we, nowadays, live in a hybrid media system. In 'Politics in Age of the Hybrid Media', Chatwick et al. (2016) explain how ‘newer’ and ‘older’ media are more and more interacting with and in social, economical, and political fields. In these interactions, actors have an important role: “Actors create, tap, or steer information flows in ways that suit their goals and in ways that modify, enable, or disable others’ agency, across and between a range of older and newer media settings” (Chadwick, 2013: 4). This system is based on power relations between actors in different fields. We see for instance, how Thierry Baudet influences the political field, but also socio-cultural fields when he is, for instance, talking about keeping Dutch traditions Dutch, such as Black Pete. Baudet also supports the new Dutch broadcasting operation Ongehoord Nederland (Unheard Netherlands) which exclusively promotes Black Pete on its channels.

Another important understanding to look at is media logic(s). “Media logic identifies how assumptions, norms and visible artifacts of media, such as templates, formats, genres, narratives and drops have come to penetrate other areas of social economic cultural and political life. (Chadwick, 2016). We see that actors are constantly checking which combination of media is appropriate for sending their messages. Now lets seehow Baudet does this.

Baudet on Facebook

In 2019 Brandpunt+, a Dutch investigative journalistic organization, researched how much money FvD spent on Facebook advertising. In December 2019, the party paid almost €80.000. Sixty percent of those ads were meant to acquire new members. As a result they acquired 9000 new members, not all of whom came via Facebook, however it isstill a remarkable number if compared to other parties (Snelderwaard & Van den Berg, 2020).

Digital campaigns are now a new way of gaining (political) power: “The fact that the internet has allowed campaigns to harvest massive amounts of behavioral and demographic data about supporters and other citizens gives campaign teams new sources of power” (Chadwick, 2016). We have seen this during the elections of 2016 in the United States as well (Agrawal, 2019). Just like Baudet, Trump uses social media as an instrument and weapon for his politics.

A Facebook post of FvD, deleted by Facebook, because of 'claiming false statements'.

(Translation: "When does the absurd framing stop? The unfounded lies must stop!")

Can we say it is fair to campaign via Facebook? Well, all the Dutch parties seem to campaign via multiple social media accounts, but according to the research of Brandpunt+, FvD does not follow the rules drawn up in the Dutch privacy law (Snelderwaard & Van den Berg, 2020). This can be undemocratic, since FvD gains in that way more members than other parties. They do this by searching for people who are already interested in FvD or who were already targeted by Facebook. Facebook also manageswho visits the FvD website, but also looks at who registers as a new member on that site. Facebook does this because it gets paid for every new member FvD gets. But, in the cookie notice of the party’s site, nothing is mentioned about this and that is critical.

Fake news on Twitter

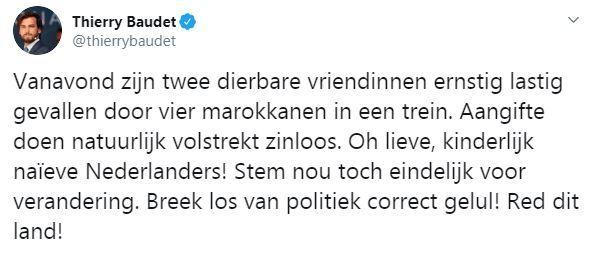

In early 2019, Baudet was accused of spreading ‘fake news’ after posting a tweet in which he mentioned that two female friends of his had been bothered by two Moroccan men during a train journey. He said that informing the police would be useless. A lot of people reacted to his post, wondering what the usefulness was of mentioning the ethnicity of the men. The NS (Dutch Railway Company) reacted the next day, clarifying that the two ‘Moroccan men’ were train inspectors in plain clothes. The train company also said that the two women did not want to show their tickets, because they didn’t recognize the men as inspectors.

The tweet of Baudet, saying how friends of him were bothered during a train journey.

(Translation: "Tonight two close friends were bothered by four Moroccan men in a train. Reporting is of course useless. Oh dear, childish naive Dutch people! Finally, vote for change. Break free from politically correct bullshit! Save this country!")

After this, Baudet tweeted that he posted this story too fast, without too much thinking. He mentioned that he put ‘the issue too hasty in a broader political context” (Boersema, 2020). The context Baudet refers to, is one he understands as an omnipresent feeling of intimidation and fear among the Dutch population by mass immigration and integration problems. He deleted the tweet.

Of course, events, as described above, focus the attention of the media on Baudet. Media are taking advantage of this because they benefit greatly from clickbait. How important clickbait is, is stressed by Venturini: ”lowering the barriers of the attention market and merchandising fleeting attention, the hit economy encouraged the development of a clickbait industry that is responsible for much of the disinformation discussed in this chapter.” (Venturini, 2019 citing Graham, 2017, p. 12).

We can find another example of (clickable) fake news on the YouTube channel of FvD. In September a video was posted in which CDA (Christian Democratic Party) MP Pieter Omtzigt was shown giving answers to Baudets' questions. In reality, he was answering a question of another MP, Sjoerdsma. FvD edited the video to make it look like Omtzigt was answering Baudet, which was not true (RTL Nieuws, 2020).

How can we look at this as a problem of fake news? Well, some videos of FvD are clearly made to let people believe in certain positions. But in this case, the video ‘might include acting as monetizable clickbait for viral content pages, doing issue work for grassroots activist groups, grassroots campaigning work for political loyalists, and providing humor for entertainment groups' (Bounegru et al, 2018). There is no other reason for FvD to post this. But the video itself is not completely fake, the information in it is verifiable on facts.

According to Venturini’s From Fake to Junk News (2019) this kind of content cannot be really called fake news. He argues for calling it junk news because that doesn’t imply the understanding of something being ‘fake’ or ‘unreal’. We can see, for example, how Donald Trump uses the word ‘fake news’ to describe traditional media like CNN and others. We can see Thierry Baudet doing the same with the Dutch news agency NOS. Baudet often calls the organization ‘fake news’, because NOS headlines are according to him ‘false’. Why does Baudet do this? Calling something 'fake' or giving an alternative view on a popular news subject, creates attention. Baudet plays on the feelings that right-winged supporters have about fake news, but in particular about the Dutch media, which are according to them, providing fake news. We have seen that the COVID-19 pandemic has been a great way for right-winged politicians to gain attention, by providing an alternative look on how to tackle the virus. By calling NOS (and other Dutch media) fake news, he provides a solution: his own YouTube channel.

FvD-news on YouTube

Baudet does not trust the regular Dutch media, one of the reasons his party has its own news program on YouTube called FvD Journaal. On YouTube, his party can freely discuss opinions, without having (objective) journalists asking difficult questions (NOS, 2020). We can see that other Dutch parties and influencers started YouTube journals as well, such as SP and SGP. In an article from NOS, media historian Hub Wijfjes calls this pillarization 2.0 (the pillarization was a period in the Netherlands where media, church, and social institutions all were categorized by political preference and creed). It was according to Wijfjes: “a time when media were only aimed at their own supporters. A combination of confirming that they were right and fighting the other group” (Boersema, 2019). Something we see nowadays with the uprising of YouTube channels and the existing Facebook pages.

Baudet himself is fond of playing and using the camera as an instrument, even during debates in the House of Representatives.

How is this part of a hybrid media system? FvD is using an ‘older’ form of media, a newscast, but airing it not on regular TV, but via YouTube. Therefore, its shareability is huge. Not only that, Baudet and his FvD make use of how the algorithms of YouTube lead people into conspiracy theories - which TV host Arjen Lubach made clear here - as digital technologies enable individuals and collectivities to plug themselves into the news-making process, often in realtime and strategically across and between older media systems (Chadwick 2011). As concluded by Bergmans (2018): “Their (FvD) targeted and sometimes provocative statements fit into the format of commercial mass media and are picked up by the algorithms of social media. As the fastest growing political party on Facebook, they clearly know how algorithms work and they are not afraid to use them as a strategy.”

So, we see some circumstances occurring around Baudets’ presence in the media. He makes his own news program, ignoring journalistic involvement. FvD is not afraid of using tricks in editing videos and thereby spreading junk news. Campaigning via Facebook is done by every party, but FvD's is tricky, as we have seen. How does this influence the hybrid media system?

Different fields, social, economical, cultural, and political, are active in this system. In a modern democracy, in which Baudet is active, opinions and political preferences are formed mainly via a public sphere. In an ideal public sphere, as Habermas (1989) wrote, media would inform their public with objective information, but as Bourdieu (1996) made abundantly clear 'how the commercialization of mass media and the quest for the highest ratings, created a stage for extreme-right antidemocratic politicians, promoting hatred and racism’ (Diggit Wiki). As Thompson (2020) states: “the power of the established media organizations to shape the agenda is disrupted by the emergence of a plethora of new players who are able to use communication media to interact with others while bypassing the established channels of mediated quasi- interaction.” Actors, such as Baudet, create their own ‘sphere’ with their own political news and information. There is no objective newsgathering anymore.

Nowadays, Thierry Baudet and his Forum voor Democratie, have maintained their own spot in the Dutch (regular) media field. As an actor, Baudet is actively spreading his ideas and opinions on social platforms in ways that are fairly new. Not only does Baudet argue about controversial subjects, but the way how he presents them and influences his receivers is also controversial and sometimes remarkable as well. This means, that in a commercialized media system, attention will be given to his excesses. Attention means clicks and clicks mean money for media organizations. Thierry Baudet benefits abundantly from this.

References

Agrawal, AJ. (2019, July 15). How Digital Marketing Changed the 2016 Presidential Race and Will Change 2020’s. Entrepreneur. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

Bergmans, N. (2018, December 27). How Forum voor Democratie puts itself in the spotlights. Diggit Magazine. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

Boersema, B. (2020, Februari 3). Boze politie overweegt aangifte tegen Thierry Baudet om ‘Marokkanen-tweet’. Trouw. Retrieved November 8.

Boersema, M. (2019, March 23). Ongrijpbaar, paradoxaal, pragmatisch: wie is Thierry Baudet? Trouw. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

Bounegru, L. Gray, J. Venturini, T. Mauri, M. (2018). A Field Guide to Fake News and Other Information Disorders. Amsterdam: Public Data Lab.

Bourdieu, P. (1996). On Television. New York : The New Press

Chadwick, A. (2011). Britain’s First Live Televised Party Leaders’ Debate: From the News Cycle to the Political Information Cycle. Parliamentary Affairs, 64(1): 24-44.

Chadwick, A. (2013). The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chadwick, A. Dennis, J. Smith, A. P. (2016). Politics in the Age of Hybrid Media: Power, Systems, and Media Logics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

DWDD (2014, November 20). Vrouwen versieren met Julien Blanc: Thierry Baudet en Geraldine Kemper. De Wereld Draait Door. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

Habermas, J. (1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Heylen, K. (2019, March 21). Wie is Thierry Baudet, de controversiële rijzende ster in de Nederlandse politiek die premier wil worden? VRT. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

Houthuijs, P. (2020, November 14). Allemaal een eigen journaal: van FvD tot SP en van Akwasi tot Maurice de Hond. NOS. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

Ke-leigh, M. (2019, March 20). The online world of Thierry Baudet and Forum voor Democratie. Diggit Magazine. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

Maly, I. (2018). Nieuw Rechts. Berchem: Epo.

RTL Nieuws. (2020, September 25). Online filmpjes zijn het nieuwe politieke wapen, maar 'het effect is beperkt’. RTL Nieuws. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

Snelderwaard, T. & Van den Berg, E. (2020, April 8). Zo werd FvD de grootste partij van Nederland. Brandpunt+. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

Thompson, J. B. (2020). Mediated Interaction in the Digital Age. Theory, Culture & Society. 37(1): 3-28. doi:10.1177/0263276418808592

Venturini, T. (2019). From Fake to Junk News, the Data Politics of Online Virality. In D. Bigo, E. Isin, & E. Ruppert (Eds.), Data Politics: Worlds, Subjects, Rights. London: Routledge.