Viral music on TikTok

With the quick rise of the TikTok app with its enormous user base of over 850 million monthly active users, all kinds of new cultural practises arise in the social media ecosystem. One is the specific place for music on TikTok.

In this article I take a closer look at the usage of music on TikTok, and how songs can rise to virality on this platform. This virality can have various consequences for the music and the artist, also outside the TikTok platform. I will illustrate this using a case study of music artist Ricky Montgomery, for whom two songs went viral on TikTok, as well as multiple other examples following similar viral trajectories, and what unintended consequences this virality has had for them. Because TikTok offers such specific opportunities for music, I will also be looking at the increasing amount of music that has intentional TikTok strategies.

Technological affordances

Before going into the case study, it’s important to first take a closer look at some technological affordances in the TikTok app that makes the virality of music possible. For every TikTok one encounters, there is a possibility to navigate to the ‘sound’ the TikTok uses. Every TikTok sound has its own page where all the videos using this specific sound are collected. On this page, there’s a button stating ‘use this sound’, which navigates you straight to the video recording menu where you can record or upload your own video imagery and connect it to this sound. There’s also the possibility to save sounds, and from this saved sound collection one can also create a video that uses it. All these functions promote the easy redistribution of sounds: with just a few clicks, some music, talking, or any other audio file is added onto a video. These technological affordances are important because the easier it is to use any sound, the more users will do so. And this is exactly what happens: on TikTok, new ‘trends’ are surfacing constantly, where people do a specific dance or follow a comedic template. These trends are often connected to a specific sound. Because users can navigate to the sound from any video doing this trend, trends are easily reproducible.

Ricky Montgomery

One artist who experienced this virality with not one, but two songs is Ricky Montgomery. Virality started off when Montgomery’s Mr Loverman gained traction on TikTok, eventually amassing over 130K videos spread over two TikTok sounds of the song, as well as at least 60K more videos spread over various edited versions of the sound, such as slowed-down or live versions. In the middle of the Mr Loverman virality, Montgomery’s song Line without a hook took an even bigger leap on TikTok, with over 300K videos on the TikTok sound of the song as of January 2021. Both these songs were released in 2016, so it’s remarkable that they amassed renewed and bigger popularity 4 years after their release.

This virality doesn’t just exist in a vacuum on TikTok, its popularity has all kinds of broader consequences. One of the clearest is streams on platforms outside of TikTok, namely the platforms the music is hosted on. Montgomery’s Mr Loverman jumped from around 7 million streams on Spotify in July 2020 to 64 million streams at the beginning of January 2021. The streams for Line without a hook also at least quadrupled in this timespan. Both songs featured on popular Spotify Viral playlists such as Global Viral 50 and the Global Daily chart. Being added to Spotify playlists that have plenty of followers again amplifies the already existing virality on TikTok. Montgomery's number of general monthly listeners has jumped from 500K in July to 5.8 million as of January 2021. Number of monthly listeners is a very fluid metric, as they go down again if virality fades over the month and people do not seek these songs again, but certainly there is some lasting popularity, as Montgomery quickly became more well-known.

The impact of this virality doesn’t stop with just increasing numbers. They open new opportunities. In Montgomery’s case, increasing popularity brought the opportunity of getting signed to a record label. This isn’t a unique case: singer Tom Rosenthal also experienced virality on TikTok when his cover of Home released under Rosenthal’s pseudonym Edith Whiskers amassed over 700K videos on the sound. On this Twitter page, he also described how record labels have reached out to him because of TikTok.

.

Figure one: Tom Rosenthal tweeting about record label opportunities

More examples of record label deals following TikTok virality can be found, showing that record labels are increasingly aware of the opportunities that TikTok provides for musicians and the labels.

Gatekeeping

TikTok virality isn’t all positive, however. One interesting negative consequence that occurred when Montgomery’s songs went viral, and also in many other cases of virality, is the phenomenon of gatekeeping. In the specific context the term is used here, gatekeeping refers to the process where users determine who fulfills enough of the right conditions to rightfully refer to themselves as a fan or listener of something or someone. Gatekeeping echoes the notion of enoughness as described by Blommaert & Varis (2011): to have enough features to be recognized as a proper member. Enoughness and gatekeeping refer to the TikTok process in which users are establishing boundaries to who can identify as Ricky Montgomery listeners and fans.

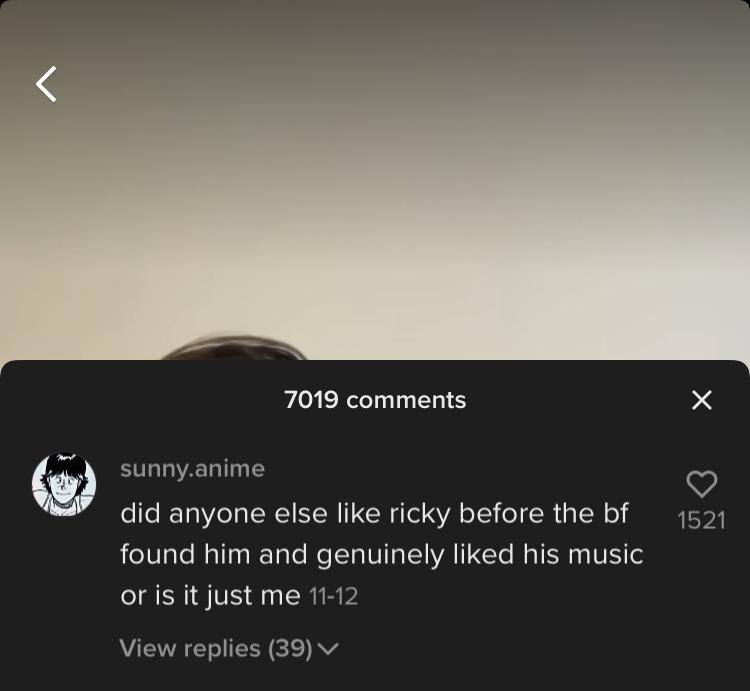

The first way in which gatekeeping occurs in Montgomery’s virality is through the debates on fan identity. One major factor in the virality of Mr Loverman is an anime called Banana Fish. Fans of this anime connected the song to specific characters and meanings in Banana Fish. The Banana Fish fandom was even mentioned in the end credit of Mr Loverman’s music video. Because of this new connection, a debate arose among some Ricky Montgomery listeners, as is seen in figure two.

Figure two: fan commenting on one of Montgomery’s TikToks.

Here, the user emphasises how they already liked Ricky’s music before the Banana Fish fandom found him, meaning before his TikTok virality. On many other posts by Ricky or mentioning him or his songs, users emphasise how long they have been listening to him. While comments like these aren’t negative on their own, they can be interpreted as users feeling the need to emphasise that they were a fan long before the TikTok virality, which in turn could imply that some regard fans who have discovered him on TikTok in the last few months as ‘lesser’ fans.

Figure three: reply to one of Montgomery's tweets

The type of gatekeeping shown in Figures two and three has to do mainly with fan identity and debates on who is the 'better' or 'lesser' fan. This is not the only form of gatekeeping that occurs. Gatekeeping can also have to do with wanting to keep the artist as a ‘secret’. This especially happens with less well-known artists, where listeners specifically appreciate the fact that the artist is not well-known, and they would like to keep it that way.

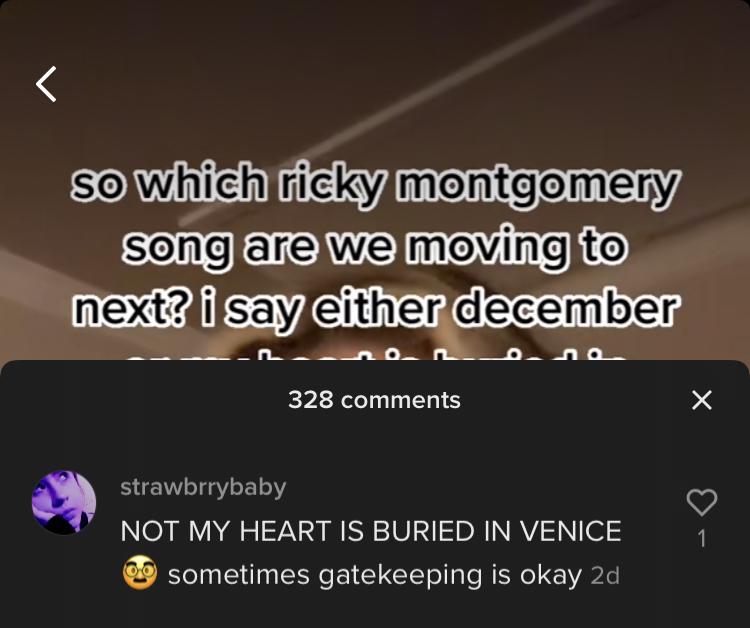

Figure four: comment by user @strawbrrybaby on a TikTok asking about what Ricky Montgomery song the fandom should try to trend next.

This theory of specifically appreciating an artist who is less well-known is made explicit for example in the following comment, on a video that is not about Ricky Montgomery, but about gatekeeping music in general. The text on the TikTok states “Anyone else gatekeep music but like. in secret”. From the fact that the video has nearly 5K comments as well as over 100K likes it is visible that gatekeeping is a wide-spread phenomenon.

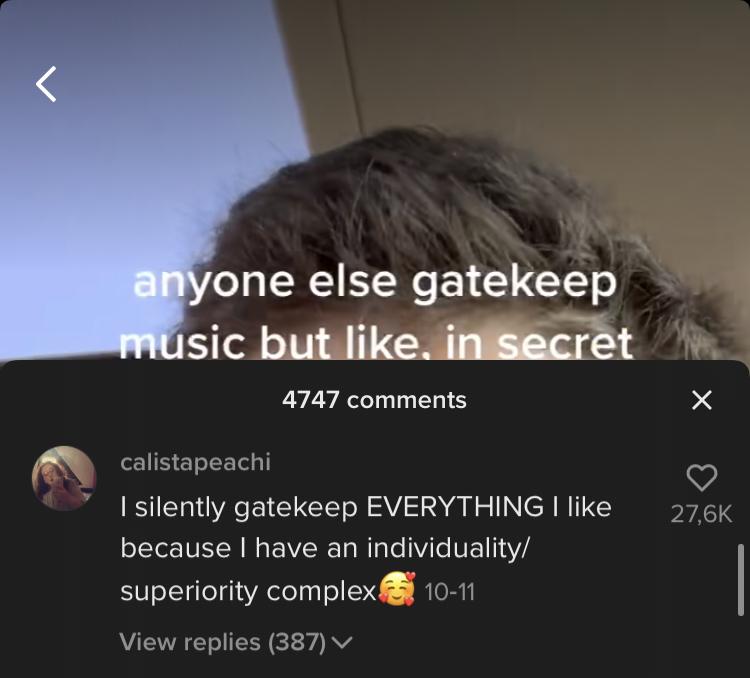

Figure five: user @calistapeachi mentioning gatekeeping because of an 'individuality complex'.

The user in this comment indicates that they secretly gatekeep lots of music, for the exact reason mentioned above: because listening to a smaller artist makes them feel unique, individual or superior. Because they want to preserve this feeling, gatekeeping occurs.

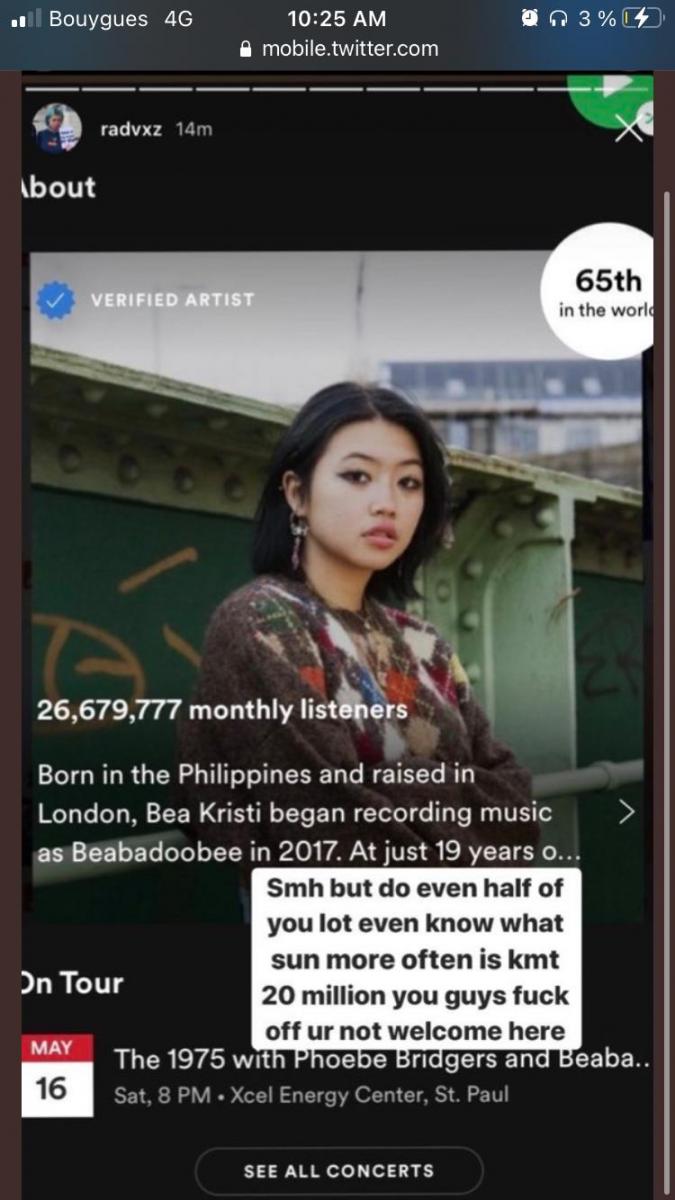

In these examples the action of gatekeeping is performed by the listeners, occasionally it can also be performed by the artist, as in the case of Bea Kristi, known as artist beabadoobee. A remix of her song Coffee went viral on TikTok earlier in the year, causing a massive spike in her monthly listeners. However, as seen in Figure six, she was not very happy about this, expressing how she doubts that listeners know any other song than the Coffee remix. This is also a way of gatekeeping: complaining that listeners who are only there for the Coffee remix are not welcome as true fans.

Figure six: singer beabadobee talking about her hitting 20 million listeners on Spotify

As becomes clear from these cases of gatekeeping, gatekeeping is mostly a mental process for individual fans: if a song goes viral on TikTok, there is not much chance that a few fans can stop the quick rise of this song. Therefore the main impact of gatekeeping is discourse in the fandom communities, it will likely not have much impact on the actual streams and listener numbers of the artist.

(Un)intended consequences

Most of these opportunities and perils that were brought by the virality of a song can be described as what Bowles (2018) refers to as unintended consequences: when a certain bit of technology is used in unexpected ways. TikTok is generally characterized as a video and dance app, not necessarily as a platform for music distribution or promotion. Yet it is being used for this purpose, the consequence is unintended, though in most cases not necessarily unwanted. As for the case study, Montgomery did not have a major strategy in place that actively worked on the promotion of these songs on TikTok. But now that the possible impact of TikTok on music distribution becomes more visible, we can see how both record labels and artists become more aware of the possibilities that TikTok can offer, and do explicitly include the platform in their promotional strategies.

An example of this is this TikTok by Miley Cyrus, in which she invites fans to make TikTok videos using her new song Prisoner. This promotion stimulates rather organic use of the music, as users willingly make videos with this sound. TikTok promotion can also go another way that is less organic: to pay popular TikTok pages to make one or more videos using the music. Often a dance or another easily copyable trend is attached to the song, in the hopes that the followers of the big accounts will catch on so that a promoted trend will continue organically.

Larger impact

Because TikTok makes it so easy to make, save, edit, repost and remix content, users constantly attach new meanings to the songs, as well as adding shared meanings through the creation of trends. These processes raise questions about the ownership of the meaning of music. Ricky Montgomery expressed that he did for example not like a TikTok about spreading the gospel that used Mr Loverman as an audio. Here we see a conflict in ownership: especially when it’s made so easy by TikTok to use music in one’s own way and have the possibility to distribute it on a large scale, it’s hard for artists to gain control if they do not want their music to be associated with this meaning.

From this case study and all the examples that follow similar trajectories of virality and impact, it becomes visible how valuable TikTok can be for artists. Though this impact on music was in all likelihood an unintended consequence of the TikTok app, that doesn’t make it any less significant. Some consequences discussed in this article are increasing streams posing new opportunities such as record deals, gatekeeping as a negative consequence, debates on the ownership of meaning, and artists and marketing teams being increasingly aware of TikTok’s possibilities for music promotion. These are not the only consequences that the TikTok platform has for the music industry. TikTok’s impact fits into the larger pattern of an increasing need for artists’ presence on social media, as well as new forms of marketing that have to be developed specifically for these platforms.

References

Blommaert, J., & Varis, P. (2011). Enough is enough: The heuristics of authenticity in superdiversity. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, 2, 1-13.

Bowles, C. (2018). Future Ethics. NowNext Press.