Will the Chinese Social Credit System be implemented in the EU?

For years, China has been the leading country in terms of agency and social control. The country’s government has implemented the latest digital technologies to build social order and reduce crime. In 2014, the People’s Republic of China became a center of the world’s attention with the launch of the Chinese Social Credit System announced by the government.

Many Western countries have kept a close watch at this innovative phenomenon, projecting the possible outcomes, perceiving it as a threat, or predicting similar innovations occurring in more parts of the world. In the years following the first Social Credit System annoucement and its implementation in China, we see both the benefits and the pitfalls of this innovation, as well as its implementation in other countries following suit.

The Chinese society background

The People’s Republic of China is an influential actor in World politics. With its century-long traditions and prominent history, the country is currently in the position in which it is slowly regaining its position as one of the international leaders.

The People’s Republic of China has one of the fastest-growing major economies in the world (Scheffer, 2019). In the last few decades, China has been expanding its internal and external ambitions. The Chinese policies are aimed at the country growing bigger, faster, and stronger in all the accessible fields. The country has also been projecting its “sovereign claims over Taiwan, Tibet, South China Sea, etc., China regards territorial integrity as a fundamental part of sovereignty” (Pan, 2010). The intensely growing state has proved to be the rising power and authority in the world.

For all its rapid industrialization and economic growth, China has also become one of the world’s leaders in digitalization, technology, and surveillance. The country uses facial recognition, the network of monitoring systems or the so-called system of mass surveillance, internet monitoring, and monitoring through mobile devices, to establish social order and control.

The facial recognition concept.

Such developments are not a coincidence, they are a historical pattern. China made its first steps in the direction of the establishment of total control over the population during the Maoist era. In this era, the country invented a mechanism of control that would spread across the whole nation to strengthen the power of the leader in the newly established government (Chang, 1952). Technological progress has made this surveillance ideology more rapid and unified.

What is the Chinese Social Credit System?

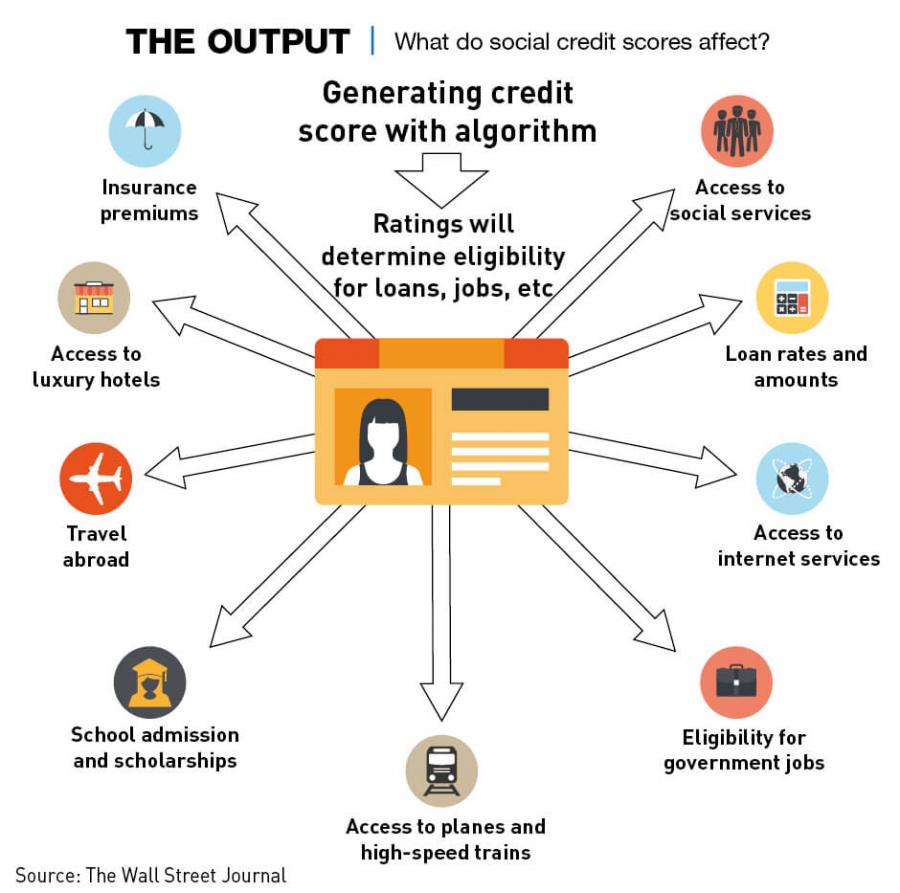

The Chinese Social Credit System has a function of gaining and maintaining social reputation, visible to others. Depending on this reputation, citizens can have full or no access to certain social benefits, such as trips, education, specific jobs, insurances, and others. The Social Credit System is “framed as a set of mechanisms providing rewards or punishments as feedback to actors, based not just on the lawfulness, but also the morality of their actions, covering economic, social and political conduct” (Creemers, 2018).

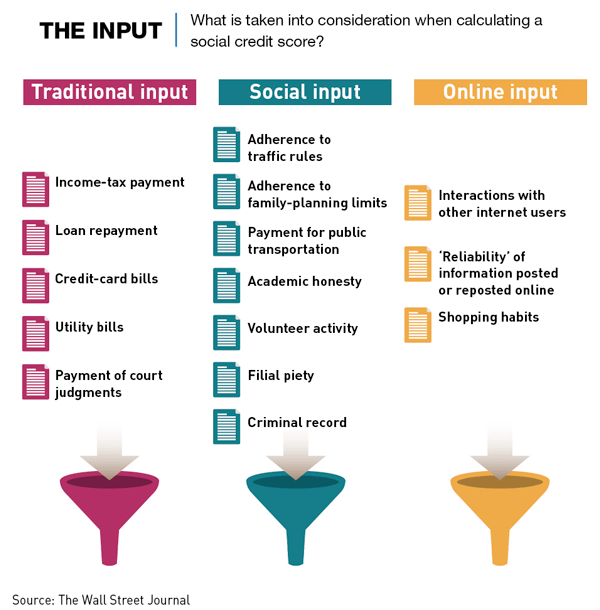

The information is analyzed by the Social Credit System deals with the patterns of online behavior, personal relationships, activities he or she interacts in, tax and purchase histories, websites visits, time spent online or playing video games, school grades, bank account history, work successes, relationships with- and the quality of one's network, and many others. All of this information is then gathered in one place, with the possibility for anyone to view and judge it. Citizens’ personal data is then locked in the digital dimension, determining the trustworthiness for the broader public. The list of collected information goes on for as much as personal data could tell about the individual.

Information affecting The Chinese Social Credit System score.

However, the scope goes way beyond one’s computer or mobile device. The system includes street surveillance, meaning the fines given to an individual on the street, would immediately be displayed in the system. Because companies are also active users of the credit system, the rating customers give to the employees of a specific firm would also be shown be added up to the overall profile information of the citizen.

Every traceable move of the individual is then fixed, which aims at increasing the government control and social order of the Chinese citizens. If people know that they are being watched, they tend to change their behavior drastically. Here, we can see a direct connection with the real-life notion of the “panopticon” by French Philospher, Foucault. He uses it as a metaphor for describing social order and control. Inevitably, having a reputation at a stake, one is tempted to adjust his/ her habits, which increasingly eases the maintenance of control over the populations.

The phenomenon of the Chinese Social Credit System is that it is rather inescapable. Due to the rapid digitalization, it is impossible to ‘go under the radar’ since all the data gets systematically collected and stored in the cloud.

The implementation and functions of the Chinese Social Credit System

The system takes the concept of the widely used scoring system, implemented by FICO- the company that measured the risk of giving away bank credits to particular individuals, collecting and analyzing their personal data. While the FICO concept was introduced nearly 60 years ago, the Chinese interpretation is slightly more modernized.

The Sesame Social Rate interface Concept.

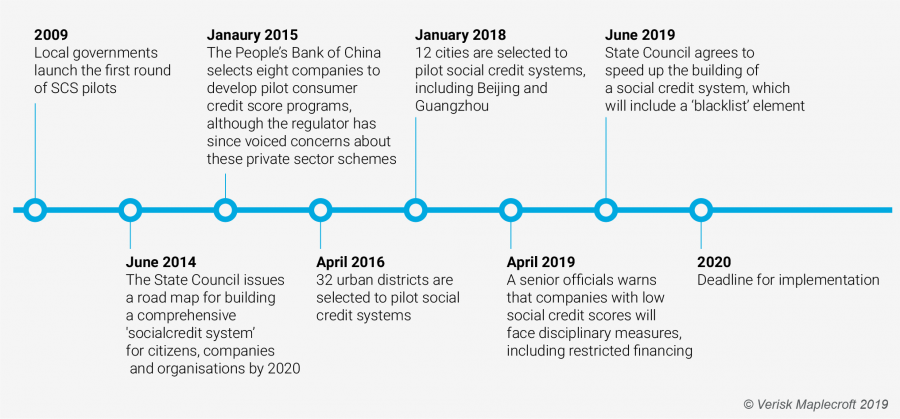

The system has been further developed by the Chinese government. However, its implementation was not an immediate process. The launch of the Chinese Social Credit System was announced in 2014 and immediately became a worldwide press sensation. The country published the Social Credit plan outlining the further development of China and all the branches of the society in line with data collection and surveillance.

The Chinese government slowly started implementing the system. One of the main functions of the Chinese Social Credit System is to increase the influence of the State amongst the citizens. “The high priority of forestalling threats to the integrity of China’s political system have fuelled an increasingly powerful security state” (Creemers, 2018).

In 2015, the first tests on the system began. The People's Bank of China licensed eight top firms in the country to start a trial of the Social Credit System (Hornby, 2017). Ultimately, multiple companies started using Social Credit System to improve their services and manage their employees.

The score affects of the Chinese Social Credit System.

Slowly, the system has entered many spheres of citizens’ lives. In 2016, the government published the list of activities, forbidden to the owners of the low rating:

- a ban on working in government institutions;

- denial of social security;

- very careful inspection at customs;

- a ban on holding senior positions in the food and pharmaceutical industries;

- refusal of air tickets and berth in night trains;

- refusal in places in luxury hotels and restaurants;

- the ban on the education of children in expensive private schools. (rbc.ru)

In 2018, the first documented cases of refusal of train and air travel were noted, when numerous people appeared on the transportation blacklist (Chan, 2018). Some dating apps, like the matchmaking platform Baihe, reportedly offered their users an option to share their Sesame Score rate (Hatton, 2015). If a parent had a low score, his or her children were no longer allowed to enter top educational institutions.

The Chinese Social Credit System timeline.

Social Credit System and corporate interests

What remains rather inexplicit is the cooperation between corporate interests and the State. Currently, there are two scores, Sesame Score and the official Social Credit System. The Sesame credit score is provided by Alibaba Group, based on a set of digital payment and financial transactions of the users. How the former feeds into the latter is vague, which is a concern in the society in which many people feel that there needs to be a clear separation between the two.

Sesame Score and the Social Credit System operate differently. The former rewards good behaviors by, for example, being an element in applying for visa to foreign countries. However, unlike the Social Credit System, the Seasame Score cannot punish. Banning an individual from traveling would be up to the Social Credit System since Sesame Score does not hold as much power.

In relation to Sesame Score and Social Credit System, there is an issue of trying to foster closer cooperation between the digital industry and the government. Sesame Score collects information on thousands of different variables and takes into account a range of financial and social behaviors, provided by Big Data (Campbell, 2020). The social debate concerns digital privacy and to what extent can the State have access to the sensitive information of its citizens.

Personal score divides the poor and the rich

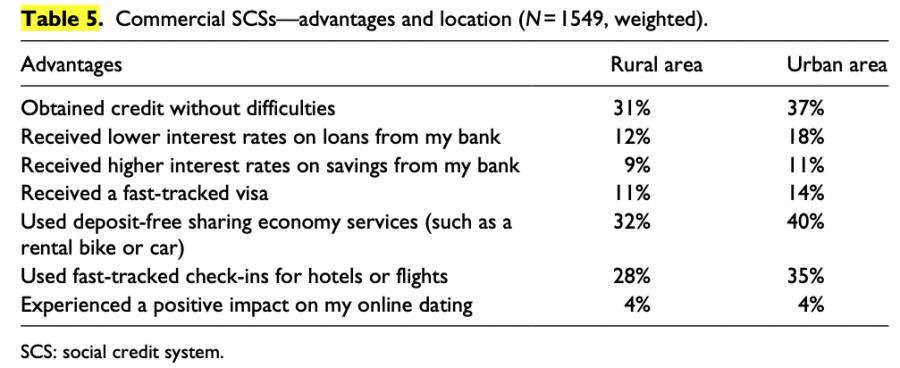

When talking about the social score, the debate is often framed as a problem of 'authoritarian state vs. the people'. This view is quite limiting because it shifts away the attention from the broader public response to the issue. Simply put, a domestic dynamic in the perception of the system differs — the wealthier and older people show strong support for the system, while the socially disadvantaged citizens not so much (Kostka, 2019).

Kostaka (2019) illustrates "that urban respondents received a wider range of benefits" in comparison to the responders from rural areas.

The reason for such a division lies in inequality. Well-educated, wealthy citizens, particularly from urban areas are the primary beneficiaries of the credit system (Kostka, 2019). This part of the population also tends to interpret the functions of credit systems beyond the frame of privacy issues (Kostka, 2019). For wealthy citizens, the scores are more than just surveillance. They are associated with obvious benefits and perception of the system as "an instrument to improve the quality of life and to close institutional and regulatory gaps, leading to more honest and law-abiding behavior in society" (Kostka, 2019) and partly reflect the State's rhetoric.

The more disadvantaged citizens, on the other hand, may end up getting even less access to social benefits depending on their scores. The systems counting citizens' reputations risk initiating an even wider gap in society, which is evident from the ongoing public debates between the camps of 'the rich' and 'the poor'.

Social Credit System in the media

The Social Credit System was portrayed locally as a new strategic plan and perceived as an essential step of the country’s development initiated by the local Communist Party. In the Chinese media, it is described as a massive advantage for society, initiated by the State.

The Chinese media have quite a positive rhetoric regarding the Social Credit System. It is expected to reduce crime and financial frauds, bring peace and order to the state. One of the leading arguments is that the Social Credit System is the way to keep track of the financial flows, which so far have been uncontrolled: a significant part of the Chinese population does not use bank cards and tries to avoid official financial institutions.

This perception has to do with the use of security as the main guarantee of social order and peace: "security is then, conceptually, reduced to technologies of surveillance, extraction of information, coercion acting against societal and state vulnerabilities, in brief to a kind of generalized “survival” against threats coming from different sectors, but security is disconnected from human, legal and social guarantees and protection of individuals." (Bigo, 2008). In a nutshell, the system is greatly aimed at collecting information from the citizens, promoting this process as if it will significantly improve Chinese society.

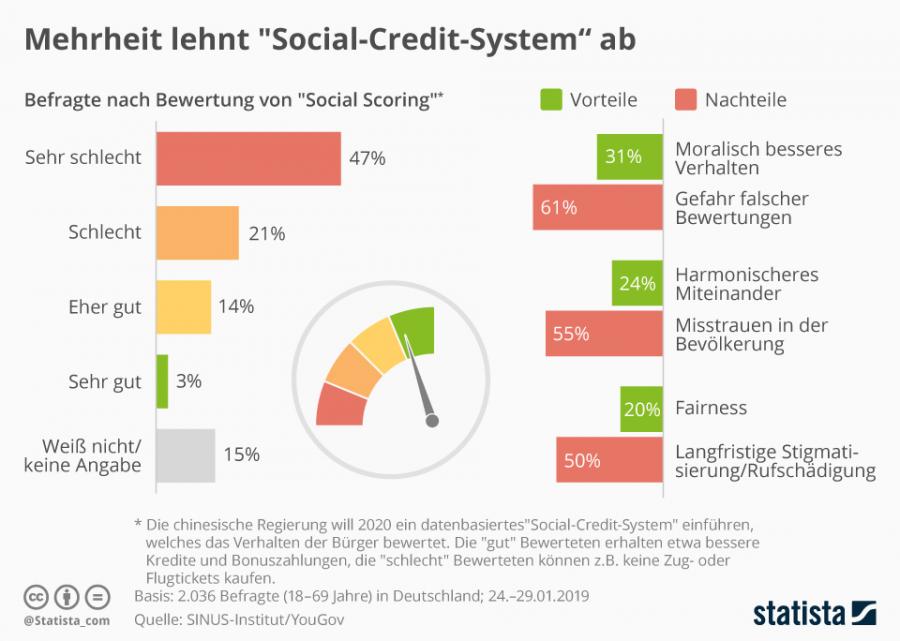

The Chinese Social Credit System on the German media sources. The 'majority' (47%) finds the System 'very bad'.

The essential part of the Social Credit System, which has become a matter of numerous discussions in Western media is that citizens will have to rate each other. Many compare this system to a utopic episode from the television show Black Mirror, entitled 'Nose Dive'. In the series, the main character is so deeply concerned with her social credit that she fully adjusts her life to get the response of positive feedback and eventually has a mental breakdown from this pressure. Many see it as a probable scenario of the outcomes of the system.

Generally, Western mass media have been claiming the system is dystopic, describing it as “Big Data meeting Big Brother”. Many of the European politicians and ordinary citizens have voiced their disapproval of the system, calling it a violation of human rights. Generally, many sources have displayed their fear, opposing the idea of a similar system being implemented in the EU.

The Social Credit System in the EU

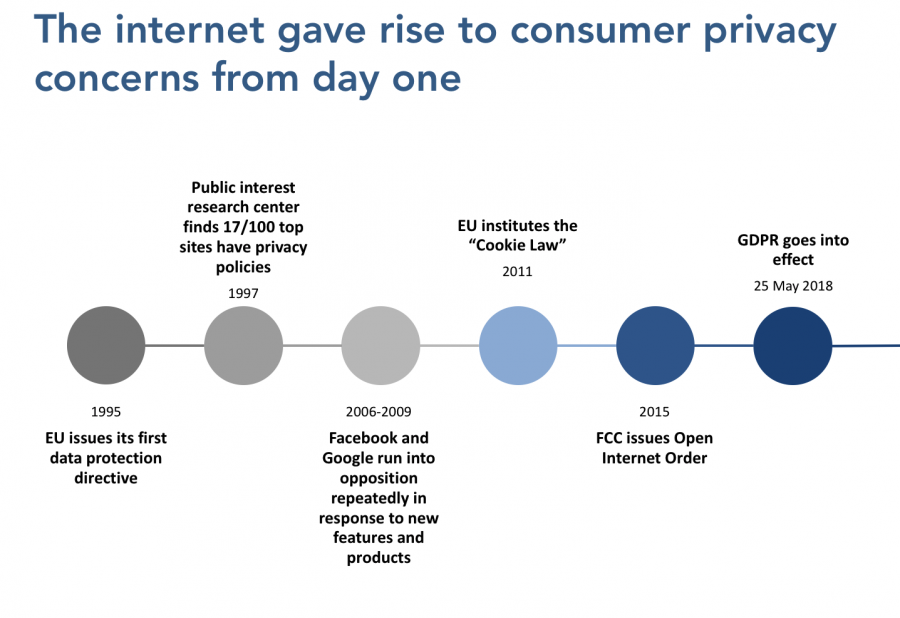

In 2018, the European Union updated its data privacy and its cybersecurity laws. The strengthened sanctions have provided Europeans with more security over their personal information: “organizations that process personal data [became] regulated not only if they are established in the EU, but if they target goods or services at, or monitor the behavior of, individuals in the EU—regardless of where they are located” (Kalman, 2019). The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has become a marker of the EU’s interest to secure its citizens in the online field.

Actions preceding the implementation of GDPR in 2018.

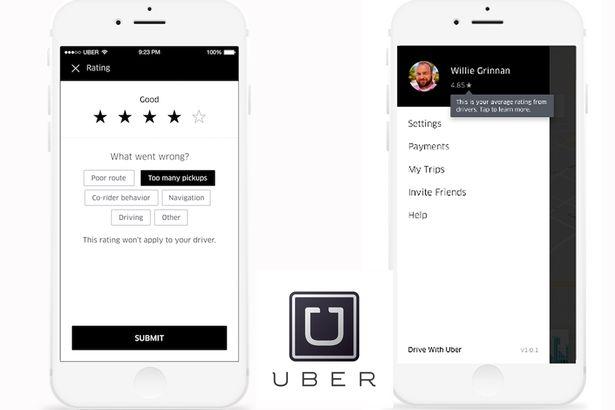

However, while the Chinese Social Credit System has been massively criticized in the ‘Western’ media, Europe has been gradually moving towards applying some of the System’s innovations. One might say that Europeans have already been rating each other for quite some time. For example, we grade our Uber drivers, fulfill university surveys, or we might be rated as workers in certain recruitment nets. Engines like Google, Facebook, or Amazon also track users' purchase history, interests, and location. However, for many of the EU citizens, this has not yet turned into something bigger than numerous filter bubbles and targeted commercials.

Even though the Chinese Credit System might seem like a faraway reality for the Europeans, it could be closer than expected. The reputation measurements, like the one invented by FICO, have been working within the borders of the EU for years. European citizens evaluate their Uber drivers, the restaurants they eat in, and the courses taught in their universities. Some websites allow people to leave comments on their employers and employees. Banks look at individuals' account histories to make decisions on issued loans. Even on major social media websites, like LinkedIn, one can leave recommendations on the users. All in all, there is a well-functioning credit system. The only difference is the smaller and more diversified scale of its scope and the fact that it is not a common European policy as yet, thus, there are no unified regulations to it taken by the government.

Example of Uber driver rating.

In both China and in the European Union, the first steps towards the merge of data collection and surveillance have taken place via the business firms. Money flows from China to Europe have been influencing this process. There is no fixed number of how much has China invested in the European market. For years, China “had longstanding diplomatic [as well as economic] ties with the European Union” (Lisbonne-de Vergeron, 2011). However, “although the exact scale of Chinese investments, including assets acquired remains unclear, large operations seem to have been ‘marginal’, with investments mostly supporting Chinese exports to Europe and acquiring specific skills in dedicated technological sectors” (Lisbonne-de Vergeron, 2011). The intensity and the scale of investments to the EU determine the influence of Chinese investors on the European market. The more money flows run into Europe’s firms from abroad, the more power they have to control some of its processes. If the Chinese side demands adjustments to the work structure of the firm, such as the implementation of the local Social Credit-like reputation system, and even more if it is willing to sponsor these innovations, many of the companies would have an uneasy decision to make on their policies.

The same goes for European companies operating in China. When the firm enters the Chinese market, it is supposed to apply all the necessary conditions and regulations established by the State. “If you are a multinational or a foreign company operating in China, you already accept all kinds of restrictions that you would not accept in any other country [...]. Therefore, if you have a sufficiently good reason to be in China, you are not going to be deterred simply by the social credit system being introduced." (Tsang, 2019).

It is clear that the implementation of the Social Credit System in Europe will massively depend on the political ties with China, “and that commercial interests will come first until that relationship fundamentally changes” (Sullivan, 2019). For years, the relationship between the two has had numerous misunderstandings, due to “the perceptional gap on key concepts, such as sovereignty, human rights, democracy, and stability” (Pan, 2010). Currently, the economic ties between the two are becoming more interconnected, with China investing in the EU is “a change of strategic emphasis in Beijing to encourage more diversified capital exports, with a special focus on Europe” (Lisbonne-de Vergeron, 2011).

One can argue to what extent the Social Credit System could be implemented in the European Union. However, the small elements of the system used locally within companies, give a glimpse of the possibility of the further spread of the rating system in the society. In many ways, the further deepening of the system will depend on business and economic relationship with China that can easily influence its implementation, starting from the local level within the international companies.

However, one thing is clear that should a monitoring system be fully implemented in the EU, the rhetoric of it will be very neutral. The Social Credit System would be represented as an advantage for society, as it was done in China. Of course, the rhetorical tone would be more neutral in the EU with the precise attention to human rights and European values of becoming a better society.

So, what are the odds?

After the announcement of the Chinese Social Credit System in 2014, it influenced the discussions on privacy and data collection around the world. In many aspects, the innovation began to influence the lives of the Chinese citizens by taking into account their personal ratings, giving all or no access to the social benefits of the country.

The media response to the reputation measurement was picked up and represented in different rhetorics both in the People’s Republic of China and abroad. Although the new system was heavily criticized in the ‘West’, there is still a chance that gradually elements of the system will be implemented in the EU.

Already used in many companies, banks, and online applications, the system is becoming more normalized in our everyday lives. The speed and the intensity of the implementation process also depends on the amount of the Chinese investments to the European market.

Even if such a credit system will be fully implemented in Europe, one thing is clear that its rhetoric will be maximally neutral and the speed of its application will be slow. This will be done in line with the framework of the ‘European values’ and common good for the universal European goals.

References:

Bigo, D. (2008). Globalized (In)Security: The field and the Ban-Opticon. In D. Bigo, & A. Tsoukala (Eds.), Terror, Insecurity and Liberty. Illiberal practices of liberal regimes after 9/11 (pp. 10 - 48). Abingdon: Routledge.

Campbell, C. (2020). How China Is Using "Social Credit Scores" to Reward and Punish Its Citizens. TIME.

Chan,T. F. (2018). China’s social credit system has blocked people from taking 11 million flights and 4 million train trips. Business Insider.

Chang,J. (1952). Wild swans : three daughters of China. HarperCollinsPublishers.

Creemers, R. (2018). China’s Social Credit System: An Evolving Practice of Control. University of Leiden.

Hatton, C. (2015). China 'social credit': Beijing sets up huge system. BBC News.

Hornby, L. (2017). China changes track on ‘social credit’ scheme plan. Financial Times.

Kalman, L. (2019). New European Data Privacy and Cyber Security Laws: One Year Later. Communications of the ACM.

Kostka, G. (2019). China’s social credit systems and public opinion: Explaining high levels of approval. Freie Universität Berlin. SAGE.

Lisbonne-de Vergeron, K. (2011). Chinese and Indian views of Europe since the crisis: New perspectives from the emerging Asian giants. English-language edition the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and the Global Policy Institute.

Pan, Z. (2010). Managing the conceptual gap on sovereignty in China–EU relations. Springer-Verlag.

Scheffer, P. (2019). Old continent in the new world. Europe and the rise of Brazil, India, and China. [Lectures]. Tilburg University.

Sullivan, A. (2019). China's corporate social credit system spooks European companies. DW.

Tsang, S. (2019). China's corporate social credit system spooks European companies. Interview for DW.

Гордеев, А. (2016). Цифровая диктатура: как в Китае вводят систему социального рейтинга. РБК.