Yellow Vests from France to Taiwan: A globalized icon of resistance

What does the French Yellow Vest movement have to do with the Brexiteers and the people in Taiwan protesting against unfair taxation on the other side of the world? These protesters beyond the borders of France came to wear this icon of resistance thanks to the digital infrastructure of modern (social) media. The internet and (digital) media enabled people all over the world to adopt the idea of wearing a Hi-Viz yellow vest in social protest. In a way, it can be said that people have come to protest in these characteristic vests worldwide because a maintenance engineer from France decided to share this idea in a video on social media.

The origin of the Yellow Vest protests

May 29, 2018. A 32-year-old businesswoman from Paris, Priscilla Ludoski, launched a petition on Change.org, in which she called for a reduction in fuel prices. The fuel prices in France had risen by 23% for diesel and 14% for gasoline in one year. When Ludoski realised the government could act by lowering taxes, she shared the petition. In July, the French government came up with a series of measures targeting motorists, which were not received happily by the French citizens. In October 2018, two truck drivers, Éric Drouet and Bruno Lefevre, called for a national blockade of roads and roundabouts to denounce a rise in fuel prices. By the advent of November 2018, Ludoski’s petition had been signed over a million times.

Meanwhile, Ghislain Coutard, a maintenance engineer, invited people to wear their Hi-Viz vests on YouTube in support of Drouet's initiative. The video quickly reached 5 million views, and when 300.000 people across 2.000 places in France took to the streets to block roads, toll-booths and vehicles, an icon of resistance had been born. From the first event shared on the Facebook group 'La France en Colere' on October 2018 till early 2019, people wearing yellow vests were seen in nearly thirty different countries all over the world.

Wearing a yellow vest in protests all over the world tells a story on the power of the internet and (social) media, and the ways in which we now rapidly communicate globally. The motor behind this fast and global spread is what Immanuel Castells calls the network society. The internet 2.0 has become a central technological structure that has reshaped society as a whole (Castells, 2010). In the case of the Hi-Viz yellow vests, the characteristics of these new digital communication structures are fully put into practice.

The Yellow Vest as an international icon of discontent

From November 2018 to June 2019, protestors wearing Yellow Vests have been seen all over Europe as well as in Canada, the US, Australia, Tunisia, Libya, Israel, Iran, Iraq and Egypt. As the Yellow Vest as an icon of resistance and discontent is adopted worldwide, the ideology behind it doesn’t necessarily move alongside it. This was a conclusion of a recent study on pro-democracy protests (Brancati & Lucardi, 2019). The researchers argued that France's Yellow Vest demonstrations were not what inspired unrest abroad because democracy protests result from local issues that are prioritized over international ones. The same idea comes up when comparing media reporting on the Yellow Vests in different countries.

As the Yellow Vest as an icon of resistance and discontent is adopted worldwide, the ideology behind it doesn’t necessarily move alongside it.

The phenomenon is better understood if we look at some examples of Yellow Vest protesters from all over the world. Whereas the Yellow Vest movement as we know it in France started as a grassroots movement without connections to a specific political ideology or political party, the Yellow Vests in Canada, for example, is a far-right movement that has been xenophobic from the beginning. The Canadians have only 'borrowed the idea', says Charles Smith, associate professor at the University of Saskatchewan. In several countries, people started wearing yellow vests while defending national issues as in the case of the Brexiteers, saying 'we voted leave'. Although groups of Brexiteers are seen wearing yellow vests, they do not emphasise the same issues as the French, but were hijacked by the far right. So, although the idea of wearing a yellow vest in social protests is now a globalised phenomenon, accelerated by the infrastructure of (social) media, and many get their inspiration from the French, they go onto the streets for local causes connected to their own countries and governments. In Taiwan, protesters 'hope that Tsai Ing-Wen will listen to people and give concessions like Macron did', but although there can be similarities, the case is never exactly the same. Some more examples of protestors 'borrowing' the idea of wearing the yellow vests, come from Iran, Israel, Egypt and Iraq, where protests were already present before the emergence of the Yellow Vest movement in France.

As the Yellow Vest as an icon of resistance and discontent is adopted worldwide, the ideology behind it doesn’t necessarily move alongside it.

The yellow vests as a globalised icon of resistance have to mobilize even Dutch protesters, illustrating how the Yellow Vests can be described as a culture scape in Appadurai's terms. The Dutch add local indexes (that is, characteristics) to the movement when they protest against Prime Minister Rutte or when they complain on Facebook about a supermarket re-naming their advertisements as a perceived favour to 'foreigners'. In these examples, we see the blending of the local and the global into a culture scape (Appadurai, 1996). In the case of the Yellow Vest movement, the index of wearing a yellow vest is the global aspect that gets blended with local reasons for protest and dissatisfaction. These reasons can overlap with reasons for protest abroad, like the people in Taiwan, Canada and France all demanding tax justice and people in the Netherlands and Iraq protesting against corrupted governments, but the protests remain based on local issues.

This icon going global could not have been possible without the existence of web 2.0. The flow of more sophisticated websites and platforms has the affordance of connecting people and their content directly to each other. It was through social media that Ghislain Coutard was able to reach millions of people with his idea that went global.

The transformation from local, fixed communities to transnational ‘imagined’ communities is the cause behind the now globalized Yellow Vest phenomenon.

The internet in the times of web 2.0 is the central technology that reshapes society, making the world transnational, dynamic, complex and less predictable. What were once stable communities have now become flexible networks focused on shared ideologies and interests. Although traditional communities still exist, we can also be members of new networks (like the Yellow Vest movement in our own country) that operate on a transnational and fully globalised level (Castells, 2010). The same transformation from local, fixed communities to transnational ‘imagined’ communities is the cause behind the now globalized Yellow Vest phenomenon. We can be part of different Yellow Vest Facebook groups simultaneously, for example being a member of 'Gele Hesjes NL', 'Gele Hesjes Tilburg' and 'Yellow Vests Europe' at the same time.

Slacktivism in the Yellow Vest movements

Although the social media from which most Yellow Vests groups have emerged do facilitate the creation of enormous events on the streets in several countries, there is also a force in social media that decreases the number of people physically protesting. How does it happen that people call for mass demonstrations on Facebook and thousands show their interest online, but only a handful of people actually show up at these events as can often be seen in news items on television?

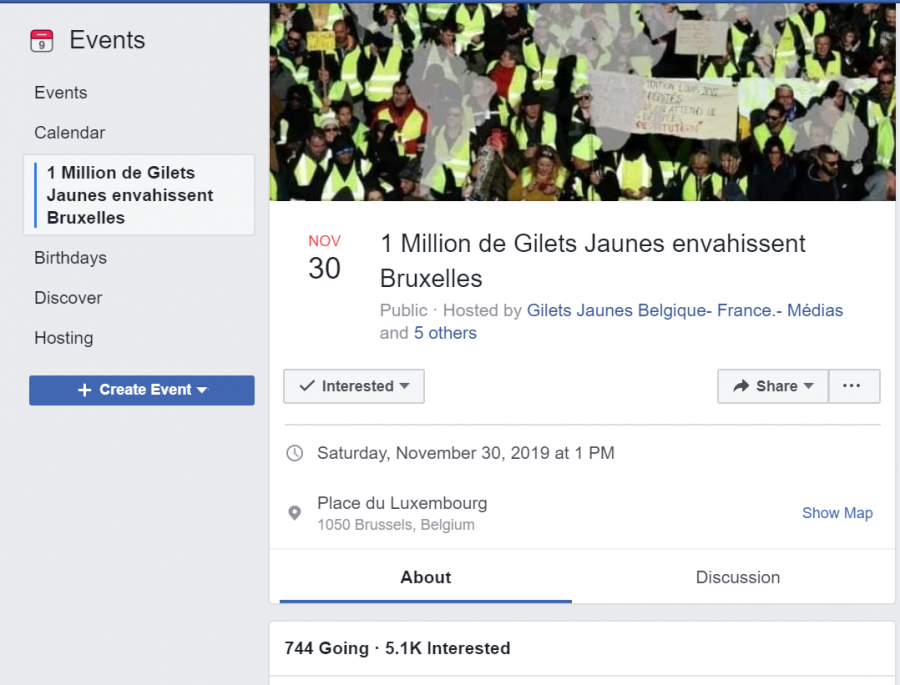

Slacktivism: 5000+ interested, 744 going

One of the main reasons for this is slacktivism. Rotman and colleagues (2011) define slacktivism as low-risk, low-cost activity via social media to raise awareness, produce change or grant satisfaction to the person engaged in the activity. Slacktivism can refer to 'liking' an activist's page on Facebook, sending a Tweet with an activistic symbol in it or altering one's social media profile picture, for example. (Social) media is often the reason why people know about social issues to begin with, but it doesn't always lead to concrete offline actions.

A social issue, according to Rotman and colleagues, starts with the identification of a social cause and the recognition of a need for awareness. Then the information and need for awareness is distributed via social media, which can either lead to activism or slacktivism (which does not leave the online space of social media). In the case of activism, direct, proactive and often confrontational action is used to attain societal change. Slacktivism is, however, more common if we look at the difference between the numbers of people being 'interested' in certain activistic actions online and of people actually showing up in demonstrations.

Mass media have a great influence on the visibility of the yellow symbol, but slacktivism is not as easy to spot as a group of people actively protesting.

In Nijmegen, the organisers of an event in May 2019, expected 500 to 2.500 people to attend the scheduled demonstration. In the end, about 160 people actually showed up according to local media. Although the moderators and admins of the Dutch Yellow Vests put great effort in mobilizing people to protest, they didn't really succeed. Despite their Facebook page counting more than 32.000 members, there have never been protests attended by more than a few hundred people in the Netherlands. Slacktivism is intended to show support towards a certain social issue on social media, but the mass media only count the number of people in the streets. For the mass media, the decreasing numbers of Yellow Vests physically protesting mean that the movement is declining.

Mass media have a great influence on the visibility of the yellow symbol, but slacktivism is not as easy to spot as a group of people actively protesting. Politicians and mass media respond to actions that have effects in everyday (mostly offline) life. When a dozen protesters block a highway, the effects are bigger than when a thousand new members subscribe to a Yellow Vest Facebook page.

Slacktivism is not local and can be seen in international events in central cities in Europe. Take as an example the picture above, a screenshot of the Facebook event made for an event in Brussels that more than 5.000 people said were interested in and 744 were intending to go to. The official Facebook page of the French Yellow Vests counts more than 1.7 million members, but the iconic protests in Paris have only attracted a few hundred people in recent weeks.

Four yellow vests in Tilburg

Nevertheless, the Yellow Vests are known even in the peripheries of the Netherlands. The election board during the provincial elections in Goirle, a village in the south of the Netherlands, was decorated with a yellow vest. Another example of the icon reaching the peripheries is a digital newspaper from Ooij, a very small Dutch village on the border with Germany, reporting on the Yellow Vest protesters in Nijmegen. Wang and colleagues (2014) argue that globalization is a transformation of the entire world system including the most remote margins. Globalization is as influential to the margins as it is to metropoles, and this is clearly seen in the globalization of the yellow vest symbol.

Where are they now: one year later

Despite the decrease in protesters, the Yellow Vests are far from gone a year after the first event in France. In fact, even new, 'spin-off' initiatives appear, like the Black Vests who fight for a better treatment of undocumented migrants. Meanwhile, the Yellow Vests have recently celebrated their first anniversary, on November 17. Organisers of the Yellow Vest anniversary estimate that about 40.000 people rallied on the birthday of the movement, whereas the French Ministry of the Interior estimated the number at 28.000 protesters nationwide.

On November 19, Dutch yellow vests visited the Dutch Prime Minister for the second time to evaluate the agreements they had made before. In Canada, where the Yellow Vest movement is an extreme-right, anti-immigrant and hate-spreading group, the Yellow Vests are in Vancouver at the moment, protesting against immigration and carbon taxes.

The conclusion has to be that the idea of wearing the iconic yellow vests in social protests has gone global by means of the network society. Because of web 2.0 and (social) media, it is possible for individual ideas or grassroots movements to reach the national and international public and to grow exponentially. Although protesters abroad are inspired by the French Yellow Vest movement and can have (many) overlapping reasons to protest, the local social issues are the main reason they demonstrate for. By the mixing of a globalised icon (the Hi-Viz yellow vest) with national aspects (for example, Brexit campaigning), the phenomenon of the Yellow Vests becomes a culture scape. The term 'yellow vests' is now often used in the same phrase as 'protesters', whereas before November 2018, these vests only had meaning in the context of highly visible clothing.

References

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Brancati, D. & A. Lucardi (2019). Why Democracy Protests Do Not Diffuse. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63(10): 2354-2389.

Castells, I. (2010). The Rise of the Network Society. Second Edition with a new Preface. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, pp. xvii-xliv.

Rotman,D,, S. Vieweg & S. Yardi. (2011). From slacktivism to activism. Participatory culture in the age of social media. Proceedings of the International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI 2011, Extended Abstracts Volume. Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Wang, X., Spotti, M., Juffermans, K. C. P., Kroon, J. W. M., Cornips, L., & Blommaert, J. M. E. (2014). Globalization in the margins: Toward a re-evalution of language and mobility. Applied Linguistics Review, 5(1), 23-44