New forms of diaspora, new forms of integration

“Integration” continues to be used as a keyword to describe the processes by means of which outsiders – immigrants, to be more precise – need to “become part” of their “host culture”. I have put quotation marks around three crucial terms here, and the reasons why will become clear shortly. “Integration” in this specific sense, of course, has been a central sociological concept in the Durkheim-Parsons tradition. A “society” is a conglomerate of “social groups” held together by “integration”: the sharing of (a single set of) central values which define the character, the identity (singular) of that particular society (singular). And it is this specific sense of the term that motivates complaints – a long tradition of them – in which immigrants are blamed for not being “fully integrated”, or more specifically, “remaining stuck in their own culture” and “refusing” to integrate in their host society.

Half a century ago, in a trenchant critique of Parsons, C. Wright Mills (1959: 47) observed that historical changes in societies must inevitably involve shifts in the modes of integration. Several scholars documented such fundamental shifts – think of Bauman, Castells, Beck and Lash – but mainstream discourses, academic and lay, still continue to follow the monolithic and static Parsonian imagination. I what follows I want to make an empirical point in this regard, observing that new modes of diaspora result in new modes of integration.

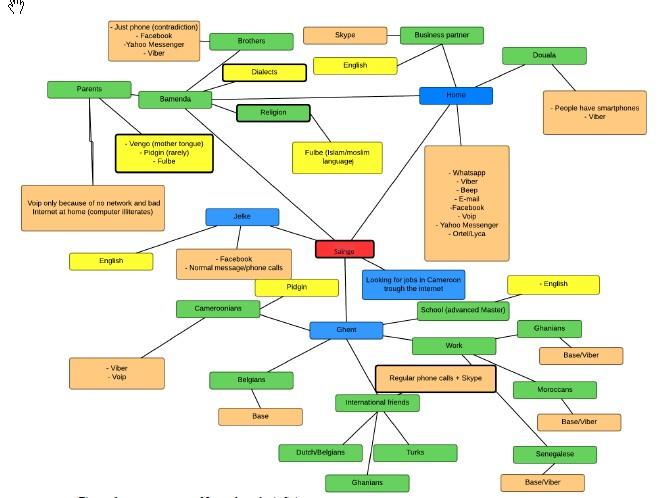

In a splendid MA dissertation, Jelke Brandehof (2014) investigated the ways in which a group of Cameroonese doctoral students at Ghent University (Belgium) used communication technologies in their interactions with others. She investigated the technologies proper – mobile phone and online applications – as well as the language resources used in specific patterns of communication with specific people. Here is a graphic representation of the results for one male respondent (Brandehof 2014: 38).

This figure, I would argue, represents the empirical side of “integration” – real forms of integration in contemporary diaspora situations. Let me elaborate this.

The figure, no doubt, looks extraordinarily complex; yet there is a tremendous amount of order and nonrandomness to it. We see that the Cameroonian man deploys a wide range of technologies and platforms for communication: his mobile phone provider (with heavily discounted rates for overseas calls) for calls and text messages, skype, Facebook, Beep, Yahoo Messenger, different VOIP systems, Whatsapp and so forth. He also uses several different languages: Standard English, Cameroonian Pidgin, local languages (called “dialects” in the figure), and Fulbe (other respondents also reported Dutch as one of their languages). And he maintains contacts in at least three different sites: his own physical and social environment in Ghent, his “home environment” in Cameroon, and the virtual environment of the “labor market” in Cameroon. In terms of activities, he maintains contacts revolving around his studies, maintaining a social and professional network in Ghent, job hunting on the internet, and an intricate set of family and business activities back in Cameroon. Each of these activities – here is the order and nonrandomness – involves a conscious choice of medium, language variety and addressee. Interaction with his brother in Cameroon is done through smartphone applications and in a local language, while interactions with other people in the same location, on religious topics, are done in Fulbe, a language marked as a medium among Muslims.

Our subject is “integrated”, through the organized use of these communication instruments, in several “cultures” if you wish. He is integrated in his professional and social environment in Ghent, in the local labor market, in the Cameroonian labor market, and in his home community. Note that I use a positive term here: he is “integrated” in all of these “zones” that make up his life – he is not “not integrated”, I insist – because his life develops in real synchronized time in these different zones , and all of these zones play a vital part in this subject's life. He remains integrated as a family member, a friend, a Muslim and a business partner in Cameroon, while he also remains integrated in his more directly tangible environment in Ghent – socially, professionally and economically. This level of simultaneous integration across “culture” (if you wish) is necessary: our subject intends to complete his doctoral degree work in Ghent and return as a highly qualified knowledge worker to Cameroon. Rupturing the Cameroonese networks might jeopardize his chances of reinsertion in a lucrative labor market (and business ventures) upon his return there. While he is in Ghent, part of his life is spent there while another part continues to be spent in Cameroon, for very good reasons.

I emphasized that our subject has to remain integrated across these different zones. And the technologies for cheap and intensive long-distance communication enable him to do so. This might be the fundamental shift in “modes of integration” we see since the turn of the century: “diaspora” no longer entails a total rupture with the places and communities of “origin”; neither, logically, does it entail a “complete integration” in the host community, because there are instruments that enable one to lead a far more gratifying life, parts of which are spent in the host society while other parts are spent elsewhere. Castells” “network society” (1996), in short. We see that diasporic subjects keep one foot in the “thick” community of family, neighborhood and local friends, while they keep another foot – on more instrumental terms – in the host society and yet another one in “light” communities such as internet-based groups and the labor market. Together, they make up a late-modern “diasporic life”.

There is nothing exceptional or surprising to this: the jet-setting European professional business class does precisely the same when they go on business trips: smartphones and the internet enable them to make calls home and to chat with their daughters before bedtime, and to inform their social network of their whereabouts by means of social media updates. In that sense, the distance between Bauman’s famous “traveler and vagabond” is narrowing: various types of migrants are presently using technologies previously reserved for elite travelers. And just as the affordances of these technologies are seen as an improvement of an itinerant lifestyle by elite travelers, it is seen as a positive thing by these other migrants, facilitating a more rewarding and harmonious lifestyle that does not involve painful ruptures of existing social bonds, social roles, activity patterns and identities.

What looks like a problem from within a Parsonian theory of “complete integration”, therefore, is in actual fact a solution for the people performing the “problematic” behavior. The problem is theoretical, and rests upon the kind of monolithic and static sociological imagination criticized by C. Wright Mills and others, and the distance between this theory and the empirical facts of contemporary diasporic life. Demands for “complete integration” (and complaints about the failure to do so) can best be seen as nostalgic and, when uttered in political debates, as ideological false consciousness. Or more bluntly, as surrealism.

References

Brandehof, Jelke (2014) Superdiversity in a Cameroonian Diaspora Community in Ghent: The Social Structure of Superdiverse Networks. MA dissertation, Tilburg University (unpublished).

Castells, Manuel (1996) The Rise of the Network Society. London: Blackwell.

Mills, C. Wright (1959 [1967]) The Sociological Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press.