International Women's (Online Shopping) Day in China

International Women’s Day has its origins in promoting women’s rights in work places and their right of suffrage. In Chinese official discourse, this day is an occasion to celebrate females' contribution to socialist construction. In recent years, however, new phrases such as ‘Goddess’ Day’, ‘Queen’s Day’ and ‘Girl’s Day’ begin to replace the word ‘women’ in the digital world, especially in promotional campaigns for online shopping. This article will delineate the transformation of International Women's Day in China and explain such change by tracing a short history of China's gender politics.

The National March 8th Red-banner Pacesetters

The official discourse of Women’s Day in China is closely associated with the image of working women and their social contribution. Each year, the All-China Women’s Federation grants 10 outstanding females the title ‘National March 8th Red-banner Pacesetter’. Obtaining great achievements in fields such as science, education, medicine and public security, they are prized as role models for all females in China. As the metaphor goes, women hold half of the sky in China’s economic development and social construction.

The state-led feminism was promoting gender erasure instead of gender equality (Dai, 2002)

However, this official discourse of Women’s Day is not free of its problems. It is a legacy of China’s socialist feminist movement in Mao’s Era. In post-war reconstruction, women were included as an important labor force to build a socialist nation. Contrasting to the stereotypical feminine character, Chinese women at that time were depicted as strong and determined in media representations (Figure 1). They wore unisex clothes with no make-up on their face. Importantly, the ideal image here conveys that women are as strong as men when working in factories and in the field.

Figure 1 Women in Posters 1960s

Contemporary theorists criticize this state-led feminism for promoting gender erasure instead of gender equality (Dai, 2002). It evaluated women with the ideal of revolutionary working-class men. The hierarchy of masculinity and femininity is not deconstructed. In other words, masculinity in terms of physical strength was worshiped as a desired feature not only for men, but also for women. The movement did not criticize gendered social roles either. One consequence was that as women became a major labor force in work places, men were still disassociated with domestic labor. This is the familiar scenario of the ‘double burden’ for women that we also observe in the Western context.

The lack of criticism towards stereotypical gender roles and conventional gender characteristics also made China’s gender politics less resistant to consumerist discourses when the country joined the global economy in the 1980s.

Although the state-led socialist feminist movement has promoted women’s status in workplace and family (Yang, 1999), there are some consequences, if not sequela, of the ‘gender erasure’ logic. As the state’s collectivist intervention retreats from the private sphere, a correction emerged in post-Socialist gender politics. Modern femininity in China is constructed with essentialized sexual differences. The ideal woman is characterized by her natural beauty as being soft and gentle. She should not be a strong woman, a woman who devotes too much to work and forgets she is also a wife and mother. The lack of criticism towards stereotypical gender roles and conventional gender characteristics also made China’s gender politics less resistant to consumerist discourses when the country joined the global economy in the 1980s. It paved the way for today's commercialization of International Women’s Day in the digital world.

The Chinese word for women: Funü

The Chinese word for ‘women’ is funü (妇女). Morphologically, this is a compound word including the meanings of ‘married woman’ and ‘unmarried woman’. This word in the legal sense refers to females beyond 14 years old. Those who are under 14 are defined as children.

Nevertheless, in popular discourse, funü is associated with married women, especially the middle-aged. The contemporary commercial culture is one of the major forces that stigmatize the word funü. Intuitively, as all the cosmetics and food supplements are ‘anti-aging’, it must be undesirable to be an old and married woman. This is a structural discrimination against women in our societies, since they are more marked by age.

Commercial campaigns began to replace the word funü with ‘goddess’ and ‘queen’ in advertisements during the International Women’s Day

Without effective feminist criticism towards conventional gender characters, the younger female population tends to distance themselves from the category funü. They want to stay youthful and claim attractiveness and availability in the heterosexual marriage market. As a consequence, commercial campaigns began to replace funü with ‘goddess’ and ‘queen’ in advertisements during the International Women’s Day. The exuberant online shopping culture in China adds fuel to this process since many web shops have large sales on the 8th of March.

Consumption entitled freedom and equality

But why should women do shopping on Women’s Day? Why is being a ‘goddess’ and ‘queen’ much more desirable than being a woman? The logic of the online commercial campaigns converges with the global post-feminist culture. Negra and Tasker (2014: 1) summarize three major tropes in post-feminist culture: ‘self-fashioning and makeover; women’s seeming choice not to occupy high-status public roles; the celebration of sexual expression and affluent femininities’ .

Instead of being a funü, whose image was associated either with a middle-aged married woman or the political-minded revolutionary forces of the 1960s, being a glamorous goddess seems to be empowering. Glamor signifies material wealth, thus implying the economic achievement of contemporary Chinese society.

The logic of the online commercial campaigns converges with the global post-feminist culture.

Nevertheless, these commercial messages essentialize the relationship between the female gender and bodily beauty. Phrases such as ‘women all like to fashion themselves from the day of being born’ are not rare. It binds women with the labor to perfect one’s body. Also importantly, the consumption-entitled freedom and power displace our attention to gender inequality in other social fields. In other words, doing online shopping on ‘Goddess Day’ promises women the freedom to choose either a dress or a pair of jeans, instead of equal payment at work or equal share of housework in family life.

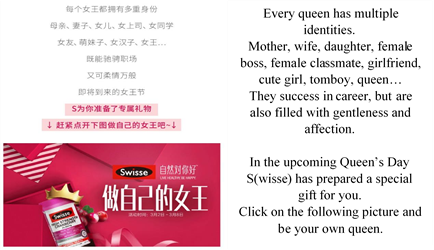

Being a ‘queen’ also has the connotation that women nowadays are in the role to give orders and make decisions. However, displaying graceful manners and classic styles are always addressed besides achievements at work, as shown in Figure 2. In other words, women’s achievement in social fields should not sacrifice their traditional femininities.

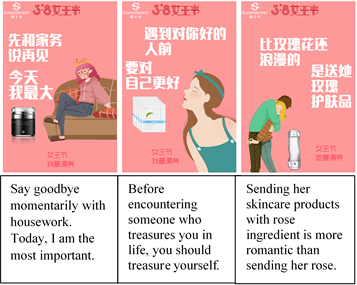

Another motif in the commercial campaigns of the ‘Goddess Day’ or ‘Queen’s Day’ is about the care of self. One reason to do online shopping at this occasion is to treat oneself. If women are always being other-oriented in taking care of family and friends, the commercial message suggests that on this special day women should invest for themselves.

Many campaigns produce the message that ‘today, you may just momentarily forget about housework’ (Figure 3). This seems to be a convenient solution, as women’s unpaid work in family life due to gendered social roles can easily be compensated by treats and gifts on this day, the symbolic value of which outweighs its economic value. Women’s Day in this case is transformed to an occasion of organized transgression where traditional gendered social normativity can be suspended, exactly for the aim to release pressure and reinforce such orders.

Figure 2 Online Shopping Campagin on 'Queen's Day'

Of course, we can also understand such campaigns as advocacy for women to be more self-oriented. This is a discourse of female individuality, which can be seen as a coin with two sides. For one side, it is claimed that women are now free from traditional social constraints. Thus, they can decide for themselves and take initiative. Like the campaign in Figure 2 says, a ‘queen’ can have multiple identities. For another, the campagin acquires a neoliberal accent since the individual becomes an ultimate solution for all social problems. That is why women are advised to treasure themselves before finding Mr. Right, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Online Shopping Campaign on 'Queen's Day'

Women are not the only ones shopping on March 8th. The online campaigns also call upon men to purchase gifts for women, for instance to buy them luxurious skincare products as shown in Figure 3. But this has nothing to do with the concept of HeForShe, which suggests gender equality should be promoted with the initiatives for all genders. The word ‘goddess’ has another context of use in China’s digital world. It refers to the desired girlfriend of a man. She is beautiful and often out of the man’s league.

In this sense, ‘Goddess Day’ brings a heterosexual relationship into the scene which is not apparent in the historical meanings of International Women’s Day. To praise a woman as ‘Goddess’ on this day is to recognize her value of being a desirable partner in a heterosexual relationship. This logic is not only heteronormative, but again renders women as a less independent subject, because they have to be defined as having a certain relationship with the opposite sex.

These commercial campaigns read harmless at first sight. Women being loved and cared about by men on this special occasion is believed to signify gender equality. In general, women receiving precious gifts and a digital red envelope (money transfer through an online payment system) on various holidays from their partners is propagated as a sign for the increasing social status of Chinese women in popular discourse. Nevertheless, this is a gendered and sexualized privilege trapping women again with stereotypical gender roles. Equalizing such privilege with gender equality further undermines feminist voices in contemporary China.

The celebration one day before: Girl’s Day

As younger females tend to distance themselves from the category of funü, another solution is found in the celebration of ‘Girl’s Day’ on the 7th of March. Its origin is associated with grassroots student festivities in Chinese universities. It is understandable that college students are young and most of them are unmarried, so they see themselves as falling outside the category of funü. However, the reason why the celebration is one day before International Women’s Day is intriguing, if not disturbing.

On the level of sociocultural customs, females are more marked by age, marriage and virginity as compared to males. This is exemplified by the variety of titles for females in English (Miss or Mrs.) and in the different hairstyles ancient Chinese women wore before and after marriage. The transition is ritualized by the wedding ceremony or the first sexual intercourse. Becoming 'a woman' in this sociocultural context is thus a sudden transition. As one wakes up the first morning after the wedding, one is reborn as a totally different person. This may explain why Girl’s Day falls on the 7th of March. The ritualistic marking of women in different life stages means that they change from a ‘girl’ to a ‘woman’ in one night. In this sense, the seemingly positive expression of youthfulness and innovation by college students is overshadowed with unspoken conservative gender norms.

'Since the day I met you, I don't watch porn any more.’

It’s difficult to evaluate the sexualizing implications in this derivative form of Women’s Day on campus. In many universities, male students hang banners to express their praise and adoration towards their female classmates. Many of them compliment their attractiveness and intelligence and most of them depict female students as desired girlfriends.

Some more explicit banners express words like ‘Sleeping with you is as romantic as the breeze of spring’ (Figure 4), ‘Since the day I met you, I don't watch porn any more’ (Figure 5). To some extent, these banners show that the young generation in China is sexually expressive. But of course, in the end these can only be understood as collective sexual harassment or animalistic courtship behaviors. At this moment, the politics of International Women’s Day has been negated.

Figure 4 Sleeping with You is as Romantic as Spring Breeze

Figure 5 I Don't Watch Porns Any More

Convergence

International Women's Day has become commerialized in a short period of time. Many factors contributeto the scenario. The exuberant online shopping culture is accompanied by the development of digital infrastructure in China. The country's economy is also relying more and more on domestic consumption rather than exporting. But more importantly, the negation of feminist politics in this process has resulted from the convergence of global post-feminist culture and China's post-socialist gender politics.

References

Dai, J. (2002) Gender and narration: women in contemporary Chinese film. (J. Noble Trans.). In J. Wang & T. E. Barlow (Eds.), Cinema and Desire: Feminist Marxism and Cultural Politics in the Work of Dai (pp. 99–150). London and New York: Verso.

Johansson, P. (2001). Selling the “modern woman”: Consumer culture and Chinese gender politics. In S. Munshi (Ed.), Images of the “modern woman” in Asia: Global media, local meanings (pp.94-121). Surrey: Curzon Press.

Negra, D., & Tasker, Y. (Eds.). (2014). Gendering the recession: Media and culture in an age of austerity. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Thornham, S., & Pengpeng, F. (2010). “Just a Slogan”: Individualism, post-feminism, and female subjectivity in consumerist China. Feminist Media Studies, 10(2), 195-211.

Yang, M. M. (1999). From gender erasure to gender difference: State feminism, consumer sexuality, and women’s public sphere in China. In M. M. Yang (Ed.), Spaces of their own: Women’s public sphere in transnational China (pp. 35-67). Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota Press.