In South Africa, April 27 is Freedom Day. In the Netherlands, it’s something else entirely

Finding Nederland...

On April 27 this year, South Africa will celebrate 23 years since the country’s first historical free and fair election. The Netherlands will celebrate King Willem’s 50th birthday on the same day. Why is this significant? Perhaps it isn’t, but considering the coincidental sharing of a national holiday between these ambiguously bounded countries, it seems poetic–doesn’t it?

South African abroad: The struggle is real

Being a South African studying in the Netherlands can feel strange and wonderful at times. At first, it was impossible to experience the place without an underlying abhorrence towards the veiled colonial past invisible to the unfamiliar eye. Every now and then the thought of Jan van Riebeeck or Hendrik Verwoerd would rear its ugly head and comparisons between colonizers and colonized would tint my spectacles a dark and oppressive grey. The feeling would worsen everytime I’d meet a Dutch person who has no idea who Jan van Riebeeck was. Since he was the Dutch colonizer who ‘founded’ South Africa in 1652, one would think he’d be a known historical figure in the Netherlands.

... comparisons between colonizers and colonized would tint my spectacles a dark and oppressive grey ...

While my perspective has changed somewhat, I cannot ignore the daily reminders of how home in South Africa is nothing like the Netherlands. Where are the (in)visible people who we satirically call ‘bergies’ or street people? Even Italy had bergies, albeit stylish Italian bergies. Where are all the racists, those people South Africans cannot distinguish themselves from in recent years? Also, why do Europeans berate me so about categorising South Africans when I identify myself as Coloured or Black, and surprisingly not White? Dutch and British descendants imposed these categories on us, after all. If we appropriated these terms to substantiate our existence in the world under extremely traumatic conditions, why are we being judged? Then, to that end, why do Europeans assume that I am White while criticising me for categorising myself at all?

There’s also the question about why I have to pay so much for a (funnily) ironic visa. Of course, it is only ironic within the confines of my irrational brain. It is that same irrational thought that finds its way to the question of why I have to jump through exasperating hoops just to travel to the Netherlands where the native ancestors needed little to conquer my homeland in the 1600s. After all, my freedom as a child in the 1980s, 300 years later, was symptomatically limited to particular areas in my own home country. My parents also stood in degrading lines in public spaces, and the families of my friends were forcibly removed from their homes in areas swiftly classified as 'white' during Apartheid.

A South African paying tribute to Apartheid the best way she knows how, at the Rijksmuseum exhibit in Amsterdam.

As a child, my mother had to walk kilometres by herself because her eyes were green enough, her hair was straight and blonde enough and her skin tone was light enough to buy food for her entire family of ten. Others were not so lucky. I’ve heard people say that these psychosocial conditions carried down from generation to generation is imagined. I ask, is the trauma carried down also imagined? Why am I so racial, and also so passionate about my country, I’ve been asked. Well, why are the Dutch not? Why does the Netherlands choose to remain an elusive trade partner to South Africa, given our incestuous history and given their part in much of the problems characterising South Africa today?

Why does the Netherlands choose to remain a neutral trade partner to South Africa, given our incestuous history?

This does not mean that I see every Dutch person as a colonizer and myself as the colonized. That would be like blaming all of South Africa’s post-Apartheid problems, even the present drought, on Jan van Riebeek alone. Blaming history has been South Africa’s Achilles heel for far too long, but looking forward does not have to mean that we forget either. Colonization happened. Apartheid happened. We cannot go back in time, as much as we wish we could. As a former Dutch colony, South Africa deserves more overt acknowledgement. A watered down display at the Rijskmuseum is just not enough, in my opinion.

Jonathan Jansen, former Vice-Chancellor of the University of the Free State, put this inspirational message on Facebook after attending Kathrada's funeral.

Yet, all is not lost – only changed. It is time to build on what has changed as a result of the past, and stop cutting our noses to spite our faces. Our fight for an equal society is unique as a direct result of our history, but it certainly is not hopeless in the face of 23 years of democratic elections. It seems like we are trying to strip our land, schools, institutions and culture of all that is European by focusing on what’s been lost and not by defining what is better. Yes, certainly Africanize! But when will we globalize?

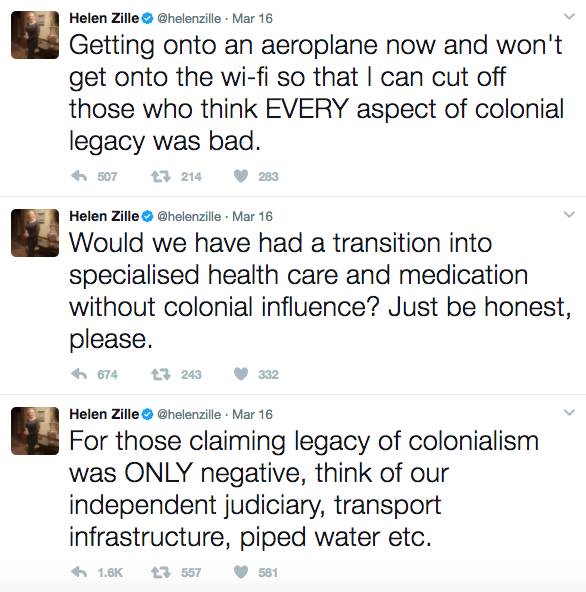

Helen Zille, former opposition party leader, is facing a disciplinary hearing with her party after a series of tweets defending colonialism.

On Freedom Day this year, my experience of King’s Day in the Netherlands will be tinged with melancholy. In recent years, South Africans saw a number of depressing realities pervade and proliferate. The Rand depreciated, as result of our president hiring and firing Finance Ministers since 2015 like contestants on a reality show. On March 31, 2017 it took a turn for the worse when President Jacob Zuma reshuffled his cabinet one more time, firing the Finance Minister the country actually respected. People took to parliament, but initially the attempt was feeble with small numbers. One week later, there was a massive anti-Zuma protest of over 100 000 people.

Before this, there was also an increase in race-related human rights violations, the former opposition party leader exposed her true colours in a series of tweets about how colonialism was not all bad, and just recently, the nation bid farewell to one of the last Struggle stalwarts who was imprisoned with Nelson Mandela for 26 years, Ahmed Kathrada. It feels a bit like we’ve taken that major step forward in 1994, only to watch in horror as we step 300 years back, within 23 years of democracy. However, now it is our own people doing the hard work of cutting each other at the knees and rendering them powerless to the status quo, as Kathrada implied in an open letter to Jacob Zuma more than a year before he died.

National days and national unity

It is just a coincidence that the King’s birthday in the Netherlands falls on the same day as South Africa’s Freedom Day. Having heard about the strong sense of national belonging exhibited on King’s Day, I felt inclined to compare how South Africa celebrates Freedom Day. Coopmans, et. al. (2015) citing David and Bar-Tal (2009) said, “A national identity–shared awareness by citizens of a society that they are members of a nation–has been theoretically argued to play a role in increasing feelings of solidarity and unity”. Their study about the relationship between national days in the Netherlands and belonging discovered that “whereas a relatively strong association with national belonging was found for Queen’s Day, for Remembrance and Liberation days this relationship was considerably weaker”. While South Africa’s Freedom Day would be considered a commemoration day such as Liberation Day, their findings did suggest a solution.

“The more frequently people participate, the stronger feelings of national belonging.”

They found, “the more frequently people participate, the stronger feelings of national belonging” and that the strength of this relationship “seemed to depend more upon the extent to which the nation was the focus of attention on that particular day”. So, it really depends on how the government chooses to deal with executing the celebration or activities. Coopmans et. al. also explained that “visibility of national symbols” on national days may play a pivotal role in strengthening the relationship; since King’s Day is “characterised by Dutch flags, orange clothing (the Dutch national colour) and a royal tour” national belonging is not as strong on other national days. Yet, I came to the Netherlands without a South African flag. Why is that?

King's Day in the Netherlands is celebrated through an overwhelming display of oranje (orange) pride - a symbol of national identity.

In South Africa, perhaps due to its sheer size and complex local relations, national days are treated with much the same vigour as Liberation and Remembrance days in the Netherlands. While the sense of national belonging is more evident on social media these days, people tend to take the time to visit wine farms, national landmarks and whatever governmental celebration they are able to find. But it is nothing like King’s Day, that’s for sure. The South African government should do better to strengthen national belonging by relooking how they handle our national days.

Remembering the South Africa that was before 1994 is always necessary, but it certainly should not be the foundation upon which all measure of South African life is determined. The foundation should be the ever-changing reality that people are experiencing locally, globally and universally. Everything aside, the question remains: what would it take for the Dutch to become active in acknowledging their historical contributions to the South Africa of today?

References

1. Baehr, P.; Castermans-Holleman, M.; Grunfeld, F. (2002). Human Rights in the Foreign Policy of the Netherlands. Human Rights Quarterly 24(4), 992-1010.

2. Coopmans, M.; Lubbers, M.; Meuleman, R. (2015). To whom do national days matter? A comparison of national belonging across generations and ethnic groups in the Netherlands. Ethnic and Racial Studies 28(12), 2037-2054.