Language in digital activism: exploring the performative functions of #MeToo Tweets

In this paper, I will explore the computer-mediated language in digital activism in regards to the #MeToo movement against sexual misconduct. Specifically, I will identify the performative functions of various posts on the social media platform Twitter which incorporate the #MeToo hashtag.

The shift of social activism to the online sphere has allowed a diverse array of individuals to weigh in and participate. No longer are people bound to a set time and physical space in order to protest something; they can contribute to the larger discussion from the comfort of home, sitting behind a computer screen. This paradigm shift calls for investigation.

#metoo and digital activism

In the era of networked societies and with the use of computer-mediated communication, information is created and disseminated across the world at an incredible speed (Castells, 1996, 2012; van Dijk, 2006). In its relatively short existence, the Internet is already undergoing a shift to being an “interpersonal resource rather than solely an informational network” (Zappaivgna, 2012). With these social affordances, many realms of our physical life exist and even shift completely to the online world: dating, completing a university degree, collaborating with colleagues, and even participating in activism.

By and through the Internet, people are taking notice, joining movements, and connecting with like-minded individuals in hopes to contribute to social change. The shift of social activism to the online sphere has allowed a diverse array of individuals to weigh in and participate. No longer are people bound to a set time and physical space in order to protest something; they can contribute to the larger discussion from the comfort of home, sitting behind a computer screen.

This paradigm shift calls for investigation. The Internet’s conditions are propitious for a social movement to ‘go viral’, and the notion appeals to many people trying to spread an ideology. However, just because a movement seems — by volume — great and powerful, doesn’t always indicate actual leverage. Online activism, characterized by critics as “slacktivism”, is a phenomenon that lives and breathes within the parameters of the digital world, potentially not oozing into offline reality (Harlow & Guo, 2014). To participate, users of social media can easily share a post, add a hashtag, or just click the “like” button. This quick and effortless input does not necessarily imply actual activity towards the movement’s purpose, nor is it indicative of mobilization. Therefore, “social media activities can be misleading as they do not show a real commitment to the cause” (Wutz, 2016).

The Internet’s conditions are propitious for a social movement to ‘go viral’, and the notion appeals to many people trying to spread an ideology.

Herein lies the question: how do we gain a better understanding of a movement’s authenticity and strength through its buzz on social media? Luckily, because connectivity is digitally documented, the progress of social movements can be tracked, analyzed, and assessed by means of new technological methods and tools such as “hashtag ethnography” (Boilla & Rosa, 2015).

This method is an important and innovative tool to explore happenings about related content. However, a “problem of engaging in hashtag ethnography [...] is that it is difficult to assess the context of social media utterances” (p.6). To overcome this pitfall, analyzing the linguistic content of the social media posts themselves can give us a better understanding of a movement’s nature and growth. Does the language about a social movement in online posts coincide with the intended frame of activism? Or does it serve some other purpose? If so, what? How? And why? Consequently what can this tell us about the movement? About society?

In this small empirical research report, I will explore the computer-mediated language in digital activism in regards to the #MeToo movement against sexual misconduct. Specifically, I will identify the performative functions of various posts on the social media platform Twitter which incorporate the #MeToo hashtag. Therefore, the research question guiding this study is:

What are the performative functions of #MeToo tweets, and how do their frequencies compare?

The #MeToo hashtag and movement has been deemed pivotal in the eyes of feminists, activists, and politicians against the culture of sexual misconduct. Its virality generated a multitude of computer-mediated communication data that can be studied to gain a better understanding of digital activism, attitudes and beliefs about sexual misconduct, and the interface of the two. Twitter itself identified the #hashtag as a legitimate ‘moment’, awarding it its own icon and bolding the hashtag when it appears in users’ tweets.

Image 1: Twitter dubs "me too" a 'moment'

Starting as an awareness campaign intended just to be a way of understanding the “magnitude of the problem” (see image 2 below), it became a platform for people to perform other actions. Aims other than spreading awareness by admitting “me too” include but are not limited to: divulging information about personal experiences, asserting knowledge about social norms, objecting to the status quo, speaking about and/or criticizing online activism, and exploiting the buzz of the hashtag to advance other ideas (see Typology below). This study, taken from a sociolinguistic perspective, is only the tip of the iceberg in analyzing the ‘goings on’ of the #MeToo hashtag and movement. It helps to expose the functions Twitter users intended to perform, under a frame of activism.

Theoretical framework

The essence of this study focuses on language in use; therefore, methods from discourse analysis will make up the theoretical framework. In order to analyze social media posts, specifically hashtag usage, it is imperative that we look at these texts as utterances aiming to engage in a larger conversation. Conversational analysis, a sociologically rooted approach to language, relies on adjacency pairs (Schegloff & Sacks, 1973); these pairs of utterances occur often in social interaction.

Twitter users used the #MeToo hashtag to enter into the broad political discussion on sexual misconduct (whether it was to join the movement or criticize ‘slacktivism’ will be discussed below). Their posts can be understood as a ‘second pair part’ in the adjacency pair theory, while Alyssa Milano’s initial tweet— which sparked the movement — can be seen as the ‘first pair part’.

Image 2: Alyssa Milano’s initial tweet

The adjacency pair is of request/response type. This explains the conversational structure of many #MeToo responses well, but it cannot help to understand the broader meaning of the tweets nor the participants’ intended behavior. Therefore, it is from a pragmatic perspective that we gain insight into what actually is going on.

Grice (1975) draws on the pragmatic fact that conversation will be logical, thereby creating the cooperative principle. He explains that there are four maxims of conversational behavior: quality, relevance, manner, and quantity. However, people often flout these maxims, and usually do so for a reason. Jones (2012) explains, a “flouted maxim itself creates meaning, a special type of meaning known as implicature, which involves implying or suggesting something without having to directly express it” (p. 54). When responding to Milano’s initial request, most Twitter users flouted the maxim of quantity, choosing to add additional information; in fact, she only said to reply “me too”, yet people wrote much more.

The violation of maxims feeds into Austin’s (1962) speech-act theory which states that utterances perform actions, i.e., they are performatives and/or speech acts. Speech acts can take the form of a declarative sentence, yet are usually not just making a statement. The speaker is doing something with their words (Jones, 2012). We can attribute the act of posting a tweet with the hashtag as ‘language to get something done’. By identifying as a person who’s been affected by sexual misconduct, people intended to build awareness and enter the larger discussion about the issue, therefore, participating in online activism. Moreover, those people who chose to add extra text (and flout the maxim of quantity) set out to achieve additional, perhaps divergent goals.

Identifying the intended goal(s) of speech acts (henceforth “performative functions”) is the focus of this paper. Therefore, understanding the forces in speech-act theory will prove to be useful. As Austin emphasized about speech acts, “it is not so much their ‘meaning’ as their ‘force’, their ability to perform actions” (Jones, 2012, p. 55). The three forces are: locutionary force (actual semantic meaning); illocutionary force (intended meaning or action); and perlocutionary force (the effect of the words on the listener/reader). During analysis of the #MeToo tweets, illocutionary force will be the principal indicator of the intended performative function.

In the case of the “me too movement”, online news articles surfaced within 24 hours of Alyssa Milano’s initial tweet (see Appendix). This gave some insight into what users of the hashtag #MeToo were accomplishing with the discourse in their tweets. Out of 14 article titles analyzed from October 15 and 16, 2017, two associated the event with “building awareness” about sexual harassment; three centered their articles around its virality; two were general information articles about the movements. The remaining seven articles commented on the fact that users posting #MeToo were sharing their personal experiences related to sexual misconduct. Therefore, a preliminary hypothesis to the research question is: The most used performative function of Twitter users employing the #MeToo hashtag was narration of personal experiences related to sexual misconduct.

In the sections that follow and with precise content analysis, I intend to uncover the performative functions of various #MeToo tweets posted on the first day of the movement.

Methodology and data collection

The #MeToo movement went viral within hours after Alyssa Milano tweeted the initial ‘request’ in the afternoon of October 15, 2017. Amidst the rising allegations of sexual misconduct in the elite sphere — namely against Hollywood producer, Harvey Weinstein — Milano decided to engage the public by offering them a way into the conversation. By the next morning, Monday October 16, “more than 40,000 people replied to Milano’s tweet” (Pirant, 2017). In the first 24 hours, her Twitter post received over 32,000 likes and was retweeted 16,000 times, while the hashtag #MeToo was tweeted nearly 500,000 times (Jarvey, 2017). The hashtag broke Twitter boundaries and was used on Facebook, Instagram, and featured in many news stories across the globe (see Appendix).

The data for this study was collected from Twitter, as it was the starting point of the movement. By employing a hashtag search on the social media site, I manually collected a sample of tweets from October 15, 2017. Of which, I omitted the most of the posts which were ‘Retweets’ and ‘Replies’ because their contexts were unable to be understood due to the embedded nature. I also did not include multimedia posts (i.e., posts with pictures and videos), as analysis of these aspects was out of the scope of this study. There were 226 total tweets, which were analyzed by both qualitative and quantitative means.

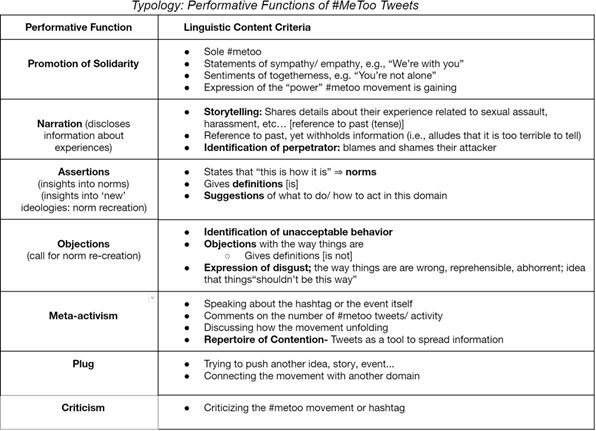

Upon reviewing the tweets and considering their performative functions, I created a typology to classify the users’ intentions based on the perceived action being carried out, i.e., what the participants were trying to do. In this preliminary research, the linguistic criteria was determined by content analysis; therefore, qualitative analysis was used to discover the in-depth understanding and underlying motives of language use.

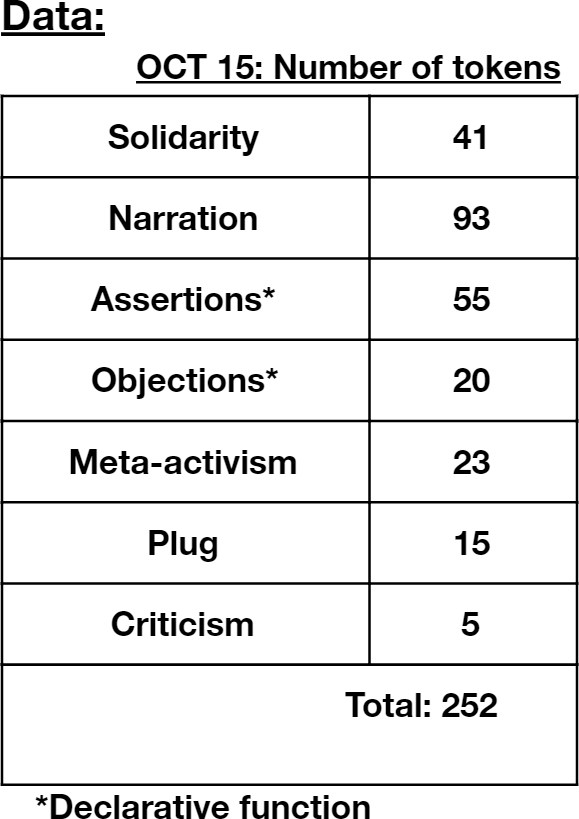

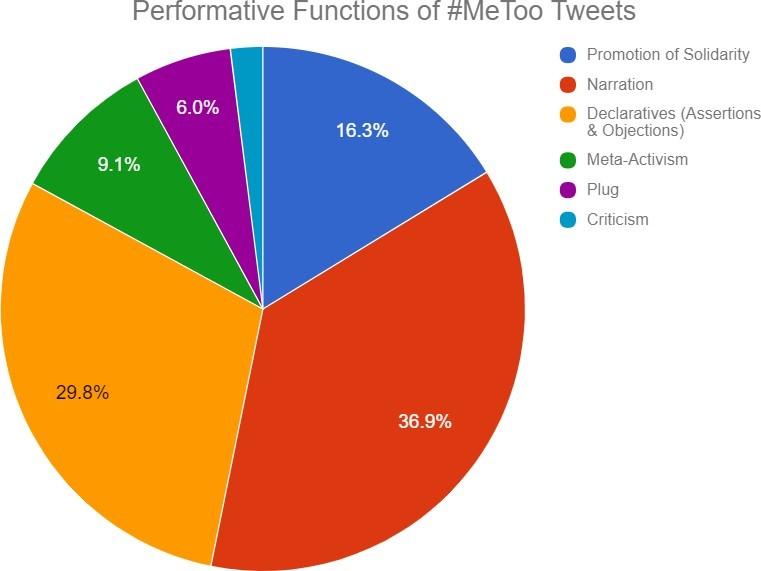

After the performative function categories were established, all of the 226 tweets were reviewed and their illocutionary force identified. Considering that one tweet can include various performative goals, I decided to count each function, regardless of its existence within a single post. There were 26 tweets that had multiple performative functions, so the total number of tokens categorized was 252. Then quantitative analysis was used to determine the frequencies and relationship of all the performative functions. This was done by using Microsoft Excel and its graphing application.

The performative functions of the #metoo-tweets

In what follows, I will present the qualitative analysis of exemplary tweets that illustrate the performative functions of Twitter users’ #MeToo tweets. User’s account names have been changed to @User or blocked out in order to maintain anonymity.

Promotion of solidarity

Users posting tweets in order to promote solidarity is the clearest form of joining the movement and participating in online activism against sexual misconduct. It demonstrates people coming together, being a support for one another, and connecting in order to protest together. Tweets with a sole “#MeToo” hashtag were included in this category, and made up 3/4 of the total tweets in this area. Example 1 demonstrates a tweet that flouted the maxim of relevance by adding more than “me too”, yet promoted solidarity.

Users posting tweets in order to promote solidarity is the clearest form of joining the movement and participating in online activism against sexual misconduct.

- @User: Sending a light and love to the people who are triggered by #MeToo it’s okay to take a break from social media.

Narration

This category included by far the largest amount of tweets. The function of “narration” and sharing stories and experiences was well-known to media outlets (see Appendix 1). Yet, it could be argued that the act of doing so flouted the maxim of relevance, as it was not elicited information. People who had experienced sexual assault were now given a (seemingly appropriate) space and time to share their experiences of sexual assault/harassment. In other words, the #MeToo prompt by Alyssa Milano became a catalyst for the expulsion of personal traumas. People took the opportunity to share their stories.

- @User2: 1st assault: Stopped in the alley next to my back door, taking out my key. Garbage collector grabbed, fondled, & kissed me. #MeToo.

- @User3: 3rd grade. High school. Bars. Gas station. #MeToo

In Example 2, we see the Twitter user narrating a story about her experience with sexual misconduct. She paints a very clear picture (albeit less than 160 characters) about the event: setting, participants, rising actions, and explicit nomination of the sexual misconduct that was inflicted. Interestingly, the order she uses for the three verbs she chooses, seems to add to the rising dramatization, as they increase with degree of severity. Contrarily, Example 3 does not explicitly name any actions of sexual misconduct that occured. However, a more implicit tactic of naming places and times was employed. The reader must deduce the meaning of the tweet, needing to have prior information about the hashtag #MeToo. Put with settings implies that this person was sexually harassed in those places/at that time in his or her life. It is the tweet’s illocutionary force, the aim to tell a story, that led classification to the “narration” category.

Declaratives: Assertions and objections

In the performative function “declaratives”, writers claim to know something about society, rights and wrongs, the phenomena of sexual misconduct, and about the world in general. Perhaps the maxim of quality is flouted here, as the claims these users make may not be entirely accurate. However, because of the sentence-type and structure of the statement, it reads as truthful. Essentially, the tweet is used as a ‘megaphone’ where the illocutionary force serves to assert knowledge onto others.

- @User4: You’d have a hard time finding a woman who hasn’t been sexually harassed at work, school, or basically anywhere. #MeToo

- @User 5: #MeToo sexual harassment doesnt discriminate. It is happening ALL AROUND THE WORLD. No matter your race, color, religion, gender, or age.

In Example 4, the knowledge asserted is that nearly all women have experienced sexual misconduct. The underlying implicature is that this is wrong, but the apathetic tone implies that it is “just the way it is”. Example 5 takes a more assertive tone, and shares with readers that sexual harassment has no boundaries, that it can happen to anyone, anywhere. The use of capital letters, a sign of increased degree of seriousness in computer-mediated communication (CMC), gives this declarative more emphasis into the issue, and implies that it be taken seriously.

The assertions seem to be comments thrown into the discussion in order to help understand what the concept of “sexual misconduct” encompasses and/or what the current situation is. One could argue that the assertions imply that the current social conventions are wrong, since they are accompanied by a #MeToo hashtag. But, more apparent contestation is with the objections. Example 6 shows a declarative statement in the form of an objection.

- @User6: Boys will be boys is NOT A REASON! #MeToo

The user is still asserting knowledge, aiming to recreate norms about what is acceptable. Her statement objects to the common excuse, “boys will be boys”, and calls readers to reassess the implications of allowing boys to act certain ways in society, e.g., regarding sexual misconduct.

Meta-activism

Tweets in this category serve as tool to expand the movement, a concept known in social movement studies as a “repertoire of contention” (Harlow & Guo, 2014). The comments about the movement itself serve to spread awareness about it and help it grow. Example 7 clearly gives a nod to the founding activist, Alyssa Milano, and contextualizes the movement adding related information. Essentially, it implies that the discussion about the culture of sexual misconduct is growing, and moreover that this movement has been a big help.

- @User7: And a special thank you to @Alyssa_Milano, who is helping women feel confident & making the conversation louder. #metoo

Plug

Some tweets incorporated the #MeToo hashtag with clear aims to exploit it to gain traffic on their Twitter page. Since the hashtag was trending, a simple search for it would include all posts that used it. Image 3 demonstrates such exploitation, as the content in the rest of the post has nothing to do with sexual misconduct, activism, or the like. This example is a clear violation of the maxim of relevance.

Image 3: Example of tweet from “Plug” category

Criticism

Tweets in this category were in fact related to the #MeToo movement, but were from the opposite point of view. They did not serve to build awareness of sexual misconduct, nor claim they were victims. Contrarily, they questioned the authenticity and criticized the movement, the hashtag, and even the people who were using it. Example 8 highlights the sentiments in this category.

- @User8: Give me a break with this #MeToo crap, 99% of you broads are lying for attention or whatever..enough, you were NOT sexually assaulted #lies

Quantifying the functions of the #metoo-tweets

Some users did indeed fill the second pair slot ‘accordingly’ by just posting the hashtag “#MeToo”. Sole #MeToo tweets accounted for 11% of the total tweets analyzed; therefore, 89% of the tweets in the sample flouted the maxim of quantity and included more text and information than was necessary.

The sole #MeToo tweets were included into the “promotion of solidarity” performative function, along with those which added comments in order to sympathize or empathize. This performative function accounted for 16.3% of the data. The majority of the performative functions were categorized into “narration” (36.9%), followed by “declaratives” (29.8%), which are seen as “assertion” and “objection” functions in the typology. The “meta-activism” category accounted for 9.1% of the total data, the “plug” category was 6%, and “criticism” totaled 2%.

Joining the global #metoo-discussion

Most Twitter users added more information than was necessary and included additional text with their #MeToo hashtag. This indicates that the majority of contributors took advantage of the opportunity the hashtag afforded and did more than just join the movement by claiming victimhood: they joined the discussion, told their story and/or gave an opinion about the culture of sexual misconduct, helped spread the word, and even criticized the movement itself. Throughout this paper, I have showed the performative functions of #MeToo tweets: promotion of solidarity, narration, assertion, objection, meta-activism, plug and criticism.

In regards to social activism, identifying the performative functions could help to determine authenticity of participation in the movement. Appropriate contributions to activism include tweets from the “promotion of solidarity” category, as well as “narration.” Communicating similar experiences and “sharing feelings in some form of togetherness” connects people and can lead to “formation of a process of collective action” (Castells, 2012, p.15). Most statements in the “declarative” category, which encouraged reassessment of norms and a call for recreation of them, can also be seen as appropriate participation to online activism. As Castells (2012) explains:

“Social movements, throughout history, are the producers of new values and goals around which the institutions of society are transformed to represent these values by creating new norms to organize social life. Social movements exercise counterpower by constructing themselves in the first place through a process of autonomous communication, free from the control of those holding institutional power” (p. 9).

The assertions aimed to define the norms currently in place in society, and the objections aimed to start the recreation process. These declaratives allude to the idea that acts of sexual misconduct are normalized, and through the #MeToo movement, calls for a stop to such normalization. “Meta- Activism” clearly fits into an appropriate form of activism as it aides in spreading the movement and generating awareness.

By exploiting the hashtag to advance another idea or gain social media attention, users did not intend to enter the political discussion of sexual misconduct. These categories obviously show misuse of the hashtag and cannot be considered authentic participation in the #MeToo movement.

The “plug” and “criticism” categories were forms of inappropriate contributions to activism. When employing these performative functions, Twitter users flouted the maxim of relevance completely. By aiming to criticize, people were not replying to Alyssa Milano’s tweet to say they’ve been a victim of sexual misconduct. By exploiting the hashtag to advance another idea or gain social media attention, users did not intend to enter the political discussion of sexual misconduct. These categories obviously show misuse of the hashtag and cannot be considered authentic participation in the #MeToo movement.

The largest category was “narration”, confirming my hypothesis. This fact warrants a further investigation, one which is beyond the scope of this study. However, a superficial conclusion could be that people (namely, victims of sexual misconduct) do not have access to nor knowledge of venting mechanisms to disclose traumatic experiences. Perhaps also they have not had the chance (an appropriate time and space) to do so in the past, and the #MeToo hashtag was the perfect pretext for them to divulge and finally let it out. This shines light on the discrete culture of sexual misconduct and the fact that it is very difficult for people to come forward.

From the screen names and photos in the tweets, most people using #MeToo appeared to be women. However, in the “criticism” category, the five tokens appeared to be from men.

Another interesting aspect discovered in analysis of #MeToo tweets is related to the gender of participants. From the screen names and photos in the tweets, most people using #MeToo appeared to be women. However, in the “criticism” category, the five tokens appeared to be from men. The assertions and objection preformative functions sometimes explicitly included women and men, respectively showing victims and perpetrators (see examples 4 and 6). This can show analysts who has the ‘power’ in the broader discussion related to the sexual misconduct, and perhaps shed light on which social actors are steering norm recreation.

Limitations and possible further research

The sample size for this study was rather small to make concrete generalizations about the performative functions used in #MeToo tweets. Also, only tweets in English were analyzed, despite the hashtag being used in many other languages. Additionally, more precise categories would have been helpful to understand the intentions more fully; for example “explicit” versus “implicit” narration, and declarative categories about norm definition, call for recreation, and objecting current norms.

For further research, one could look at each category and analyze the text more in depth. For example, in “narration”, one could analyze how social actors are being portrayed in the tweets. By identifying how social actors are represented in discourse (and thereby the acts which agents carry out), we can gain a better understanding of how society defines sexual misconduct and its culprits. Looking deeper into the “declaratives” category can help understand society’s norms from a layman's point of view.

For practical application, research in this area may help contribute to “bottom-up” language policy, clarifying legislation regarding the grey area of defining sexual misconduct.

Linguistic analysis of this data, specifically the way in which society talks about sexual misconduct, can help shed light on people’s perspectives of what is (and is not) acceptable behavior. Additionally, we can see how people are (re)constructing norms of appropriateness and (re)defining terms related to these types of interactions. For practical application, research in this area may help contribute to “bottom-up” language policy, clarifying legislation regarding the grey area of defining sexual misconduct. Additionally, understanding these ‘parameters’ gives us informational tools to promote awareness and perhaps even to educate about sexual misconduct in a way that was not embraced in the past.

Conclusion

Twitter users incorporating #MeToo into their posts aimed to achieve a variety of goals. These performative functions of tweets were at times ambiguous and interdiscursive in nature (i.e., they serve more than one purpose). With close observation of the illocutionary force, I was able to deduce the functions that were appropriate to consider as authentic contributions to social activism, while also acknowledging that inappropriate forms existed. Moving forward, it is apparent that a comprehensive analytical toolbox is needed to assess the true nature of new media social movements and their hashtag usage. This paper and the typology used can serve as a model to evaluate the underlying intentions of contributions to online activism.

References

Austin, J. (1962). L. 1962. How to do things with words. Cambridge (Mass.).

Bonilla, Y., & Rosa, J. (2015). # Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. American Ethnologist, 42(1), 4-17.

Castells, M. (1996). The information age: Economy, society, and culture. Volume I: The rise of the network society.

Castells, M. (2015). Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the Internet age. John Wiley & Sons.

Evans, A. (2016). Stance and identity in Twitter hashtags. Language@Internet, 13, article 1

Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and conversation. In Grice, H. P., Cole, P., & Morgan J.L. (Eds.), Syntax and Semantics, Vol 3, Speech Acts (pp. 41-58). New York: Academic Press.

Harlow, S. & Guo, L. (2014). Will the revolution be tweeted or facebooked? Journal of Computer- mediated communication, 463-478.

Jones, R. H. (2012). Discourse analysis. Abingdon/New York.

Schegloff, E. A., & Sacks, H. (1973). Opening up closings. Semiotica, 8(4), 289-327.

Searle, J. R., Kiefer, F., & Bierwisch, M. (Eds.). (1980). Speech act theory and pragmatics (Vol. 10). Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

Van Dijk, J. (2006). The network society. Social aspects of new media. London: Sage.

Wutz, I. (2016, April). Click here to save the world! Diggit magazine. Retrieved from https://www.diggitmagazine.com/articles/click-here-save-world

Zappavigna, M. (2012). Discourse of Twitter and social media: How we use language to create affiliation on the web (Vol. 6). A&C Black.

Appendix

News stories about the #MeToo movement, from October 15 and 16, 2017.

- Twitter sees thousands of stories of sexual assault and harassment with the #MeToo hashtag

- The ‘Me too’ movement against sexual harassment and assault is sweeping social media

- Sexual Assault Movement #MeToo Reaches Nearly 500,000 Tweets

- #MeToo: Harvey Weinstein case moves thousands to tell their own stories of abuse, break silence

- Thousands of women share experiences of sexual assault on Twitter through #MeToo

- #MeToo: Social media flooded with personal stories of assault

- Stars raise sexual assault awareness with #MeToo Twitter campaign

- The movement of #MeToo

- Incredible Image Shows How the #MeToo Movement Spread Around the Globe

- #MeToo Floods Social Media With Stories of Harassment and Assault

- WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE “ME TOO” MOVEMENT

- #MeToo: survivors testify to the impossibility of preempting sexual assault

- #MeToo: Women share harrowing accounts of sexual assault, harassment

- Alyssa Milano Starts "Me Too" Twitter Movement to Spread Awareness of Sexual Assault and Harassment