#womeninstreet as a vital extension of the female street photographer

Female street photographer Casey Meshbesher started the project #womeninstreet to celebrate female street photography. While the street photographer can be seen as Baudelaire’s flâneur, the female street photographer can be considered the flâneuse. But how does this affect the male gaze, which has dominated both society and street photography throughout history? And what is the role of social media in all of this?

#Womeninstreet: celebrating female street photography

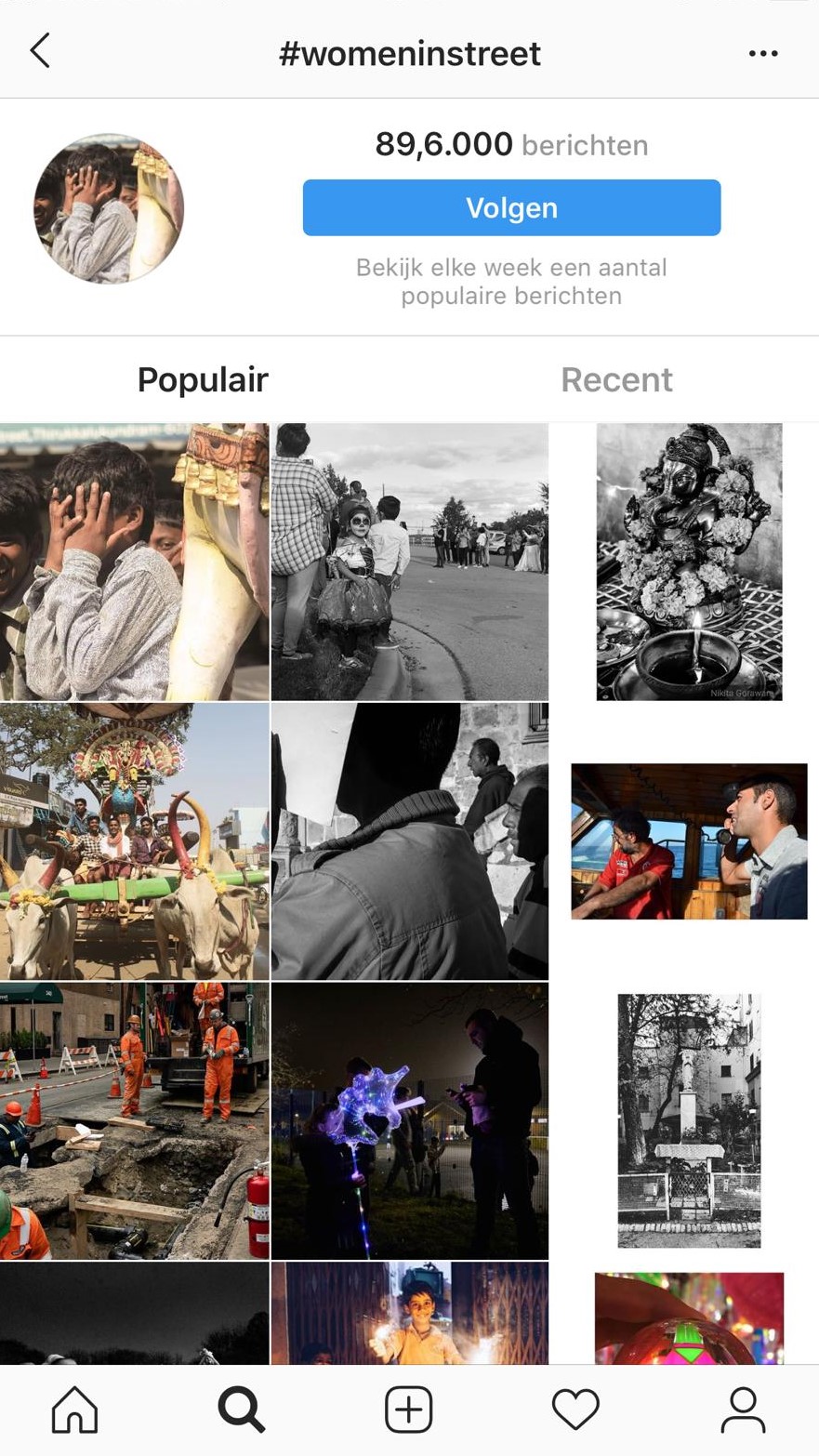

With more than 85.000 posts in total and photographs still being uploaded daily, the hashtag #womeninstreet on Instagram is growing tremendously. The hashtag was founded by photographer Casey Meshbesher, who noticed that almost no work by female street photographers could be found either online or in print. This art form has historically been dominated by men and the male gaze. Therefore, Meshbesher started the project to increase the visibility of women’s practice of photography.

Throughout history, women have been observed more often than they have been the observer themselves: due to the male gaze in both (street) photography and society, women are often objectified and commodified. Meshbesher created the hashtag #womeninstreet together with the profile @womeninstreet to celebrate female street photography. Her community can now be found on several platforms like Instagram, Facebook, Tumblr, YouTube and the blogzine ‘Her Side of the Street’. Female street photographers can submit their photographs by using the hashtag #womeninstreet. Meshbesher stated on the Facebook-page that men may participate, but that male contributors have to understand that her platform is primarily about female street photography.

Both the camera and social media are an extension of this modern flâneuse

While the photographer often is compared with Charles Baudelaire’s notion of the flâneur, this paper will interpret the female street photographer as the modern flâneuse. Both the camera and social media are an extension of this figure, which open doors for her towards visibility, resistance, and popularity. To show this, this paper will start with a theoretical framework, in which the notion of flânerie according to Baudelaire is explained. With the use of ideas of more recent theorists such as Susan Sontag, Anke Gleber, and Lauren Elkin, this figure will be transposed to the present day.

To merge their ideas with @womeninstreet, I will use quotes of female street photographers who Meshbesher interviewed for the blogzine Her Side of the Street, regarding their perspective on female street photography. To present today’s female street photographer as the flâneuse, I will first show how Meshbesher acts as a flâneuse herself, using the Instagram-profile @womeninstreet. By combining that with the hashtag #womeninstreet, I will link the flâneuse to social media and see what it does in terms of creating a community, acquiring visibility, and popularity for the female photographer. The central question is how both the Instagram-profile @womeninstreet and the hashtag #womeninstreet depict the female street photographer as a flâneuse.

#womeninstreet on Instagram.

The notion of the flâneur

French poet and critic Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) introduced the notion of flânerie in his book The Painter of Modern Life (1964; first published in 1863), to describe a man as the observer and capturer of street life in the modern city (Baudelaire, 1964: 5-6). This modern city is here seen as a metropolis that is constantly growing due to new technologies, new buildings, new means of transportation, and the aim for progress, which enables physical existence to evolve (Simmel, 185). In cities like these, the importance of visual aspects grew, which resulted in wide streets, pavement, and boulevards.

This made it possible for a flâneur to stroll about everywhere in the city (64: 36). Streets, arcades, and city halls fit this pedestrian perfectly as he was the figure wandering through these growing, industrializing cities of the 19th century (Kramer & Short, 2011: 323-324). An important characteristic of this gentleman is that he is a man of the crowd, in which he feels at home yet secluded. This means that the crowd is his element, where he is far away from home but he has the ability to feel at home everywhere.

With this, he is both at the centre of the world and hidden from it (Baudelaire, 1964: 9). He is an unseen, secluded walker in the crowd, who is interested in the whole world and has a huge curiosity that becomes a fatal, irresistible passion of his (Baudelaire, 1964: 7). Unlike the dandy, he has a sensibility that almost takes over his whole being. He is an independent, passionate, and impartial man who rejoices in wandering incognito (Baudelaire, 1964: 9).

The flâneur is both at the centre of the world and hidden from it

The arcades were seen as the most favourable terrain of the flâneur, where he could wander without a purpose, observe, and thus create his experiences (Dreyer & McDowall, 2012: 31). With the loss of arcades, the growing consumer culture and technological inventions such as surveillance cameras, the question arose whether this flâneur could still exist. In her article ‘Eye-swiping London: Iain Sinclair, photography and the flâneur’, Kirsten Seale regards the flâneur as an endangered species, which has to adapt to its changing surroundings in order to survive.

The urbanization, industrialization, and increased influence of the visual have determined the flâneur’s experience of this life, which is why Baudelaire’s flâneur is no longer limited to strolling in the streets and arcades. Therefore the notion needs to be rethought. A means of rethinking the flâneur is the act of street photography. The flâneur can be seen as a product as well as the author of the city; the street photographer can be seen in a similar way, as the product of the city as well as the author, creating a narrative with photographs (Dreyer & McDowall, 2012: 32). While wandering through the crowd, the photographer strolls without focusing on a particular aspect, but with an irresistible passion for both urban everyday life and the fashion of capturing it.

Can a street photographer be a flâneur?

In The Painter of Modern life, Baudelaire defines and characterises the flâneur clearly. This person is a man, strolling the streets of the metropolis, who feels at home in the crowd, yet is secluded from it. However, as the flâneur needs to be adapted to postmodern society, there is no longer a single definition that is adequate for this figure (Dreyer & McDowall, 2012: 32).

This paper therefore seeks to rethink the flâneur as the street photographer, since they seem to share many characteristics. According to theorist Clive Scott (1943-), author of Street Photography: From Atget to Cartier-Bresson (2007), street photography is characterised by a lack of amplified language, a staccato, jotted style, a particular worldview, and the speed of a gesture or a glance that make it easily identifiable (Scott, 2007: 3).

‘I see street photography as a core piece of the big story of who we are as humans. Making a documentation as we are in this moment'

As such, street photography can tell us something about the recovery or changing of street types and how this cultivates the urban picturesque. Hence, street photography is unavoidably connected with criminal fringes and the ambiguous relationships with the subject (Scott, 2007: 3-4). Or, as female street photographer Roza Vulf explains in an interview for the blogzine of @womeninstreet:

‘Candid, emotional brief connection with a subject is fundamental in street photography. It is essential to walk the streets with your guard down, being aware, and ready for the unexpected, that’s when it happens. It makes you see those precise moments when you get just a fraction of a second to connect with someone else’s story. It could be a reflection, a light, some facial expression, the wind, a pose, a gesture or just a sentiment.’ (Meshbesher, 2017: para 7)

Due to the candid aspect, street photography is often called a sub-genre of documentary photography with elements of narrative, instantaneousness, and peripheral angles of vision (Scott, 2007: 5). But what do all these characteristics of street photography say about street photographers themselves? Historian Gilles Mora (1945-) combines all these ideas into a single definition: ‘Street photographers pursue the fleeting instant, photographing their models either openly or surreptitiously, as casual passers-by or as systematic observers’ (Scott, 2007: 5).

As such, the street photographer exhibits characteristics identical to those of the flâneur. In a similar vein to the flâneur, the street photographer captures the life of a person passing by. Writer Edgar Allen Poe’s (1809-1849) tale The Man of the Crowd (1840) describes, according to Baudelaire, the ultimate flâneur (Benjamin, 1993: 43). The main character in this story follows someone and is eager to capture this person’s life, just like a street photographer tries to tell us a narrative of the passers-by. This idea corresponds with the criminal fringe of the photographer, who, similar to the main character in the story, may follow, observe, or even stalk someone to capture the right picture. The female street photographer, just as the flâneur, can feel the same urge to follow someone, as Elizabeth Huey notes in her interview for ‘Her Side of the Street’: ‘Photography is an art that requires hunting, searching and chasing a visual moment' (Meshbesher, 2017: para 7).

Capturing someone often happens in a fleeting instant, since it is the photograph of a person passing by rather than of somebody who is consciously posing. By capturing the person, the street photographer creates a particular worldview because the photograph can tell us something about the urban space. This, too, is similar to flânerie: while the flâneur garners meaning from urban space, he also adds meaning to urban space itself. Street photographer Ali Cherkis explains a similar experience in another interview for @womeninstreet:

‘I see street photography as a core piece of the big story of who we are as humans. Making a documentation as we are in this moment. Each photographer, though always at a distance as a stranger, will invariably be connected to the subject because they have chosen that person, that moment, that scene. It is a reflection of the photographer in that way.’ (Meshbesher, 2017: para 4)

Just like the flâneur, the street photographer captures everyday urban life, telling a story about the urban picturesque. Both can thus be seen as symbolic representations of the contemporary urban space (Dreyer & McDowall, 2012: 32).

Photography presents itself as the ideal technology to capture this brief moment and, in addition, the photographer can easily capture a large number of subjects (Seale, 2005). This technology gives street photographers the opportunity to freely roam city space, where he or she has no obsessive interest in a certain aspect of urban culture. Instead, they enjoy the ability to be surprised day by day, as Shweta Agarwal explains in an interview for @womeninstreet:

I love to interact with people while I’m shooting, to make friends with them, and to capture the essence of that place – which can include light, shadows, texture, the moment, and some story or mystery. Nothing is as exciting as street for me, it’s full of surprises and every day new things to shoot that I won’t have the next day.’ (Meshbesher, 2017: para 5)

This corresponds with the idea of the flâneur, for whom everything is equally worthy or unworthy of his attention. Neither the street photographer nor the flâneur favor particular practices or cultural products (Seale, 2005). Both have the ability to stroll and wander the streets of the metropolis, with no strict goal or purpose. With modernity being ephemeral, fugitive, and contingent in Baudelaire’s eyes (Baudelaire, 1964: 12), photography shows itself as the logical medium to express these characteristics of the metropolis. Street photographs are the visual as well as the physical dramatizations of everyday life and modernity (Seale, 2005).

The photographer can be seen as an armed version of the solitary wanderer who cruises and stalks his urban surroundings

In 1977, Susan Sontag published On Photography, in which she describes the overlap between the spatial practice of the flâneur and the photographer. She explains how photography is an extension of the eye of the flâneur, whose sensibility was a very important characteristic according to Baudelaire. The photographer can be seen as an armed version of the solitary wanderer who cruises and stalks his urban surroundings. It is a gazing stroller who discovers the city as a landscape of voluptuous extremes (Sontag, 1977: 50).

With the typical city during the 19th century being dominated by the male and the male gaze, there was no possibility for the woman to wander the streets incognito. Now that the street photographer can be seen as a flâneur, the argument can be taken one step further to find the place of the female street photographer and therefore the flâneuse.

The flâneuse

Baudelaire introduced the flâneur in the 19th century as exclusively male, since in those days women were unable to walk around in the city as freely as men. This was due to the fact that spaces are gendered, which means that public spaces are associated with men and private spaces with women (Dreyer & McDowall, 2012: 32). Because of these social norms, women were associated with the private domestic sphere, while men could (and are still able to) freely engage with the public domain and its attractions. With the rise of feminist thinking, women’s rights movements, and the fact that in today’s society gender roles are seen as fluid rather than exclusively binary, it is difficult to accept Baudelaire’s idea that the notion of the female flâneur does not exist (Dreyer & McDowall, 2012: 33).

'I was aware of the male gaze from an early age. It was easy to feel hunted'

In the article ‘Imagining the flâneur as a woman’ (2012), Elfriede Dreyer and Estelle McDowall consider different theories on the place of the flâneuse in our society. They explain how she does not have the same freedom as men do, which is inevitably connected with the fact that women are strongly associated with consumerism. In contrast to the women who were meant to stay at home rather than stroll the city streets, the prostitute is often mentioned as the woman who was visible in the streets. She, however, does not have the freedom of the flâneur to walk and roam freely, but instead, she represents the commodified female (Dreyer & McDowall, 2012: 35).

This is due to the fact that in the modern city women are seen as a part of the urban architecture, where they are something that can be observed by the flâneur and therefore consumed, just as the other components of the city. Women are thereby objects of desire due to their strong implicit association with commodification, wherein consumer products are seen as objects of desire in the city (Dreyer & McDowall, 2012: 33-34).

In her book The Art of taking a Walk (1999), Anke Gleber argues that a woman is never able to take ownership of the street, since she is always subject to the public conventions that affirm her position as an object of the male gaze. Therefore women can never enjoy a freedom similar to the flâneur's, who has the ability to gaze without being watched in return (Gleber, 1999: 72).

With the emergence of the shopping mall, an important characteristic of the flâneur had to change: with the rise of the mall and the fall of the arcades, the flâneur was no longer able to distance himself from the commodity. Thus, the flâneur had to adjust to the fact that he sometimes has to be an observer as well as the observed. This is where the feminization of flânerie comes in, and the shopping mall was thus the first place where women can be associated with flânerie, since this space gives them a sense of anonymity and the freedom to roam without a goal in mind (Dreyer & McDowall, 2012: 37).

While the flâneuse is a person who is the observer as well as the observed, she needs to be resistant to the gaze

Due to the emergence of shopping malls, increasing mobility in the city, and the fact that it became more normal for a woman to work outside of the house, women became more visible in the streets. Gleber explains that the shopping malls and the cinema were the first places where the flâneuse could appear (Gleber, 1999: 179-180). These are both ‘safe’ areas, as opposed to the streets of the city late at night, where the level of danger increases. The result of these dangerous areas is that the woman is unable to fully indulge in her fascination with the metropolis since she does not have the ability to roam the city's streets whenever she wants (Dreyer & McDowall, 2012: 40).

Whereas the movement of women in a city is restricted to a much greater degree than that of a man, the flanêuse needs to disrupt the values that confine her to ordinary life in order to be able to roam the streets aimlessly. With that, she has to become someone who is a new figure of a resistant gaze (Gleber, 1999: 84). Lauren Elkin takes this idea even one step further in her book Flâneuse (2017), in which she redefines the concept itself by describing the flâneuse as ‘a determined resourceful woman keenly attuned to the creative potential of the city, and the liberating possibilities of a good walk’ (Elkin, 2017: 1).

Here, the side of being an observed object is completely left out. Instead, Elkin focuses on the qualities of the female flâneuse as being resourceful while seeing creative and liberating possibilities. While the flâneuse is a person who is the observer as well as the observed, she needs to be resistant to the gaze. Gleber describes the opportunity for the woman to even reverse the gaze. In doing so, the woman creates the ability to stare back at the man (Gleber, 1999: 179-180). In an interview with Meshbesher for the blogzine of @womeninstreet, Elizabeth Huey explains how the camera can help:

‘I was aware of the male gaze from an early age. It was easy to feel hunted. Photography as an act of hunting is culturally reserved as an action for men. When a woman has a camera, it inverts the paradigm. I find men to be surprised when they catch me looking at them. As a woman, it demands a certain level of courage to photograph in public.’ (Meshbesher, 2017: para 7)

With a camera as an extension of her acts of flânerie, the woman seems able to shift the gaze: with photography she creates the ability to capture and observe other human beings on the streets of the city, including men. When the man is surprised to see her looking at him instead of vice versa, the woman has to be resistant and turn the gaze around.

@womeninstreet

In the paragraphs above I have shown how the female street photographer can be seen as the flâneuse but that to show this, the notion of flânerie according to Baudelaire needs to be rethought. The female street photographer can only exist if she is both the observer and the observed, since a woman is never able to aimlessly roam the streets without being observed. The camera is here seen as an extension of the flâneuse since it gives her the ability to stare at the people who pass by, including men. Due to the photographs she can capture everyday life in the urban city, by which she can create a narrative and show her worldview.

Casey Meshbesher is the founder of @womeninstreet, which is a social media project that was founded in 2016, to showcase, promote and create a community for female street photographers. The project is not only on Instagram, but also Facebook, Tumblr, a website and the blogzine ‘Her Side of the Street’. All of these platforms show the work of Meshbesher. At the same time, none of these platforms show anything of her personal life: no background information nor photo of herself can be found. Even the profile @womeninstreet, which in essence (as all Instagram-profiles) creates the assumption that it is the profile of a person, is a place where the work of female street photographers is exhibited. Where only her street photography work can be found online, Meshbesher seems to be very conscious of the role as the observer and being observed.

All of the platforms only allow social media users to observe her photographs. None of them allow the users to observe the female street photographer herself. Here a clear distinction should be made, where without any information on Casey Meshbesher herself, it is impossible to know anything about her taking a photograph. According to the theoretical framework, in real life she will never be able to be merely the observer of the streets. Where in today’s digitalised city there is no control over who gazes at you due to, for example, surveillance cameras, and where at the same time the male gaze is still present, social media and therefore the Web might be the only public place where Meshbesher can semi-control other’s observations. Might her social-media project 1. be a place to celebrate female street photography and 2. be Meshbesher trying to break from the role of being observed?

Meshbesher might not show herself literally, but her pictures can tell something about her way of gazing and therefore her worldview

On her own blog, named ‘Casey Meshbesher Photographic’, Meshbesher exhibits (a part of) her work, divided into different themes. One of these themes is street photography, which is again subdivided in themes, of which one is called ‘In this together’. All of these photographs show people in the streets of a city, together with an advertisement, an object in a random store or a statue. In figure 1, Meshbesher depicts a man who is dressed in a suit, next to a photograph inside of the shop named Hubert White, on which a part of a suit is shown as well. The suits immediately depict the stereotype of a wealthy, working man. The man behind him shows quite the opposite since he is wearing a ‘normal’, everyday jacket whilst eating a cookie on the street.

Figure 1. Photograph by Casey Meshbesher, Minneapolis 2010

Figure 1. Photograph by Casey Meshbesher, Minneapolis, 2010.

Interesting here is that both men, apart from their looks, stare right into the lens of the camera. The two men, who while looking at merely their appearances seem completely different, seem to have this thing in common: they are both gazing at the female street photographer. This photograph thus shows that the female street photographer is obviously seen by the men and is therefore unable to be the unseen observer in the crowd. According to Sontag, this is the moment that the woman has to be resistant to the male gaze in order to be the flâneuse.

This staring back does not seem the case in another photograph of Meshbesher's, also from the series ‘In this together’. Here, we see a woman, staring at something in the distance, depicted in front of a poster of the movie Maleficent (2014).

Figure 2. Casey Meshbesher, Duluth 2014.

Figure 2. Photograph by Casey Meshbesher, Duluth, 2014.

This black and white photograph compares the woman to the fairy-tale character Maleficent. The photographer here seems to portray similarities between them, for example looking at the (due to the black and white) comparable looking jacket with the higher collar, the similarly placed eyebrows and the overall composition, in which the woman stands in the centre, similar to the position of Maleficent on the poster. Here it seems that Meshbesher has the opportunity to gaze at a woman without the woman gazing back. According to cinematographer Zoe Dirse, the fact that both the photographer and the subject are women influences the photograph itself. She argues that here, the subject is depicted as she really is, instead of being depicted from the voyeuristic spectacle of the male gaze (Dirse, 2003: 436). We can thus wonder whether, if the photograph was taken by a male photographer, the photograph would have the exact same outcome.

These two photographs show a clear difference between the male and the female subject. It must be noted that these are only two examples taken from the theme ‘In this together’, which shows a variety of photographs, also showing a variety of men not looking straight at the camera. But for most of the photographs in this theme, the men do gaze back, while the women do not. There is only one woman who might gaze back, but it is unclear since she is wearing sunglasses.

The one thing that these photographs all inevitably show is Meshbesher's gaze. By putting these sorts of photographs online, Casey Meshbesher might not show herself literally, but her pictures can tell something about her way of gazing and therefore her worldview. This female gaze can thus say something about the female street photographer herself, regarding her way of looking at other people and creating a narrative. In the two figures which are part of her photo series ‘In this together’, she compares subjects with advertisements, which all refer to consumerism. With this, she might wish to show that both men and women are in today’s society determinedly associated with consumerism. This concurs with the idea that people will always enter the city through the route of commerce and consumerism (Dreyer & McDowall, 2012: 33).

#womeninstreet

Due to social media the possibility is created for artists to show and exhibit their work online, by which they can reach an audience all over the world. With that, projects such as #womeninstreet create the possibility to gain a community and a network. With the hashtag already having more than 85.000 posts and with several new posts being posted per hour, the amount of pictures is increasing and the hashtag is becoming more and more popular. With this, the photographs of the female street photographer gain visibility but also the opportunity to become more popular.

Next to this advantage, the hashtag #womeninstreet seems to create another possibility for the female street photographer as the flâneuse, which is similar to the acts of Meshbesher explained above. The difference here is that @womeninstreet is a profile on Instagram, where people consciously have to click on the profile to see the photographs.

The hashtag, however, always primarily shows the photograph. If an Instagram-user then clicks on the photograph, they can see the profile of the person who made it. Due to the hashtag, this social media platform creates the ability to stay in the shadows of your pictures, or at least people first see the photograph, then you. After searching for the hashtag #womeninstreet and scrolling through the pictures, the Instagram user can click on the profiles of the female street photographers. Here the photographer creating the profile has the capacity, just as Meshbesher did, to choose what they want to display and what not. They thus have the possibility to show themselves, their full name and their personal life, but they can also choose to show only their street photographs and to not display their real name.

Instagram therefore creates a platform where the pictures of the female street photographers are becoming more visible and some even more popular, but with that, the flâneuse herself is not determined to be seen as well. Thus Instagram might be the place where the flâneuse (and probably also the flâneur) can stay hidden in the shadow of the app, uploading her photos and therefore being one of the crowd (which is not only the #womeninstreet community, since a hashtag is visable for everybody, the crowd is everybody on Instagram), yet being secluded from the crowd if choosing to only upload the photographs and not themselves.

Can the flâneuse be a combination of a physical act and an act on the internet?

In the explanation above, a link is made from the flâneuse to the cyberflâneur. With the arrival of the internet and the social media apps, both the flâneur and the flâneuse might have to adjust once again: internet users have the ability to ‘surf’ and therefore wander the internet, watching videos and scrolling through Instagram and Facebook. The user here might not physically wander through the city, but through the CyberCity (Apostol et al., 2012: 23). A user such as Casey Meshbesher wanders the streets of the city to capture the urban space and then exhibits her worldview on a digital space such as Instagram. Can thus the flâneuse here be a combination of a physical act and an online one?

The creation of a hashtag such as #womeninstreet might mean that, at least mean for a moment, the female street photographer gains the ability to choose to be merely the observer. She therefore has, only on social media, the possibility to abandon the dominating male gaze and display her observations without being observed herself.

Escaping the gaze

At the beginning of this essay, I showed that the definition of flânerie is no longer a single definition. With the rise of surveillance cameras, the downfall of arcades and the changing urban space, Baudelaire’s flâneur has to adjust to the ever-changing society. In the modern, globalizing city which is immersed in the urban, nomadic and diasporic (Kramer & Short, 2011: 339), the flâneur might even be able to wander the web instead of the city. But before that, we can rethink the flâneur as the street photographer, who wanders the city, strolling without focusing on a particular aspect but with an irresistible passion for both urban life and the fashion of capturing it.

In order to let the female street photographer exist as a flâneuse, we need to acknowledge that she will not be able to stay fully incognito whilst wandering the streets. With this, Sontag addresses that the camera is an extension of her. With the camera, she is able to not only resist the male gaze but also to gaze back. The female street photographer is the gazing stroller who discovers the landscape of the city by capturing it with her camera. Therefore, she is the flâneuse.

Where the female figure can never merely be the observer on the streets, the hashtag #womeninstreet seems to create a temporary escape from the gaze. The photographs of a female street photographer are seen by a greater public due to a social media. Here a woman has the possibility to show her photographs, while she staying out of the spotlight herself. Where in a globalizing city the woman is still not fully able to walk freely, the emergence of the Web created the ability to at least temporarily escape this gaze.

The hashtag #womeninstreet creates a temporarily escape from the gaze

Both the profile @womeninstreet and the hashtag #womeninstreet exhibit the work of female street photographers. Where in the beginning only her photograph is shown, the Instagram-app gives a woman the possibility to only show what she wants to exhibit in this public space. On this social media app as public space, the ability arises for the female to claim her role as merely the observer, where she does not have to be objectified but where she can instead focus on exhibiting her art.

This analysis of both @womeninstreet and #womeninstreet shows that the profile created by Casey Meshbesher can be seen as an example for other women, where you can merely exhibit your photographs (or those of others) whilst not exhibiting yourself. With the hashtag not even being focused on a profile but rather on a photograph and its description, #womeninstreet is even further off from the photographer’s profile, whereby firstly the photograph itself is in sight. When Instagram-users consciously click on the photo to see the profile, the person can decide for themselves what they show. Merely the photograph itself, which depicts the female street photographers’ gaze, can tell something about her worldview and thus her personality. Meshbesher’s pictures, for example, show the inevitable link between humans and consumerism, which can tell us something about her ideas regarding this topic.

With the growing popularity of social media applications as Instagram, some questions arise regarding cyberflânerie and the various public spaces in which the flâneuse can escape the male gaze. Whether the flâneuse and the cyberflâneur intertwine in this case study or whether a social media app is the only public space for the female to break with the role of being observed are questions which need further research. With all this, one thing is sure: where in today’s society there is more awareness of the male dominance in street photography, projects as #womeninstreet play an important role for an inclusive street photography community.

References

Apostol, I., Antoniadis, P. & Banerjee, T. (2012) ‘Flânerie between Net and Place: Promises and Possibilities for Participation in Planning’, in: Journal of Planning Education and Research, vol. 33: no. 1: 20-33.

Baudelaire, C. (1964) ‘The Painter of Modern Life’, in: trans. J. Mayne, J. Mayne (ed.), Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays. New York: Da Capo Press: 1-41.

Benjamin, W. (1993) ‘The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire’, in: trans. H. Zohn. Charles Baudelaire. A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism. London: Verso: 35-66.

Dirse, Z. (2012) ‘The Gender of the Gaze in Cinematography: A Woman with a Movie Camera’ in: J. Plessis, J. Levitin & V. Raoul (ed.), Women Filmmakers: Reproducing. London: Routledge.

Dreyer, E. & McDowall, E. (2012) ‘Imagining the flâneur as a woman’ in: Communicatio, vol. 38: no. 1: 30-44.

Elkin, L. (2017) Flaneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London. New York: Vintage Publishing.

Gleber, A. (1999) The Art of Taking a Walk. Flanerie, Literature, and Film in Weimar Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kramer, K. & John Rennie Short (2011) ‘Flânerie and the globalizing city’, in: City, vol. 15: no. 3-4: 322-342.

Meshbesher, C. (28 Jun 2017) ‘Street chat with Elizabeth Huey’, Her Side of the Street. Last retrieved on 18 Oct. 2018.

Meshbesher, C. (31 May 2017) ‘Street chat with Roza Vulf’, Her Side of the Street. Last retrieved on 18 Oct. 2018.

Meshbesher, C. (8 April 2017) ‘Street chat with Ali Cherkis’, Her Side of the Street. Last retrieved on 18 Oct. 2018.

Meshbesher, C. (21 Feb. 2017) ‘Street chat with Shweta Agarwal’, Her Side of the Street. Last retrieved on 18 Oct. 2018.

Meshbesher, C. (10 Sept. 2018) ‘Women on street’, Women in Street. Last retrieved on 18 Oct. 2018.

Scott, C. (2007) Street Photography: From Brassai to Cartier-Bresson. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd.

Seale, K. (2005) ‘Eye-swiping London: Iain Sinclair, photography and the flâneur’, in: The Literary London Journal, vol. 3: no. 2.

Simmel, G. (1997) ‘The Metropolis and Mental Life’, in trans. K.H. Wolff, M. Featherstone, D. Frisby (eds.), Simmel on Culture. London: Sage: 174-185.

Sontag, S. (1977) On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.