Kneel like a true American: Protesting in American civil religion

American civil religion today leans more towards nationalism than patriotism. Originally, civil religion as a practise is meant to strengthen shared values in a community. However, this can often lead to citizens accepting national flaws in the name of patriotism. This paper focuses on why such an uncritical stance should be considered as nationalism. More importantly, it discusses how acts of protest align with the true meaning of civil religion and patriotism.

On the 1st of September 2018, history was written. Colin Kaepernick, San Francisco 49ers quarterback, refused to stand and kneeled during the national anthem during a preseason game in San Diego (Yeboah, 2016; Mather, 2019). Speaking to the media, he made clear that this act was a form of protest against racist police brutality; “(…) I have to stand up for people that are oppressed (…). I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of colour.” (Yeboah, 2016, Mather, 2019). This act of kneeling led to a movement to protest police brutality and racism: #TakeAKnee. Months after the first time Kaepernick sat down, sportsmen and -women were still kneeling, including Megan Rapinoe, captain of the USA women’s national soccer team (Mather, 2019).

While there were of course defenders of Kaepernick, the negative responses were overwhelming. Various sports players, media outlets and even Donald Trump expressed themselves on the matter and deemed kneeling unpatriotic and disrespectful to the American flag (Yeboah, 2016; Mather, 2019). The National Football League (NFL) also condemned the actions of Kaepernick, which eventually led to a ban on kneeling during the national anthem (Mather, 2019). Even though Kaepernick himself opted out of his contract after the controversy, there were suspicions that he was being blackballed from joining any clubs (Mather, 2019).

On the 1st of September 2018, history was written. Colin Kaepernick, San Francisco 49ers quarterback, refused to stand and kneeled during the national anthem during a preseason game in San Diego.

Although to non-Americans this act of kneeling during a sports game may seem fairly innocent, the response of the American people is not completely unexpected, especially in the contemporary polarized climate of the Trump era. America has always had a strong sense of civil religion, which is a set of practices and beliefs that strengthens the shared values in a society (Bellah, 1967; Lüchau, 2009; Britt, 2017). Other countries who are known to have such a civil religion are France and the former Soviet Empire. Sports can be seen as the ritualistic expression of this religion (Rogers, 1972), where there is an unwritten rule that players should not express their social critique (Peterson, 2009). If they do so, they can expect to receive negative responses (Coombs, Lambert, Cassilo & Humphries, 2019).

Even though many Americans may share this sentiment, in this paper it will be argued why the act of kneeling should not be depreciated as hateful or disrespectful towards America, but rather as a sign of 'tough love'.

Protesting in a sacred sphere?

The USA has a strong, perhaps even the strongest, sense of civil religion in the world. Even though definitions of civil religion differ, the definition by Bellah (1967) is most often used to define the prevelance of civil religion particularly in the US: “a set of beliefs, symbols, and rituals that provides a religious dimension for the whole fabric of American life” (Lüchau, 2009). Civil religion is independent of any specific traditional religion, such as Christianity and Islam, and serves as a general ‘meta’ religion (Lüchau, 2009). Examples of expressions of civil religion in the USA are the flag and the National Anthem, texts like the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence and celebrations like Memorial Day and the Fourth of July (Haberski Jr. & Nichols, 2017). Civil religion has religious and patriotic components. Ritual expressions of patriotism are part of civil religion and it expresses “a strong and uncompromising bond to the country and a resolute unconditional support for its values” (Lewin, Bick & Naor, 2016).

Civil religion is a set of beliefs, symbols, and rituals that provides a religious dimension for the whole fabric of American life

This concept of civil religion could explain the public response to the act of kneeling. Sports games and stadia are generally considered sacred in American society and are seen as a ritualistic expression of American civil religion (Rogers, 1972). The national anthem that is sung before every game and the national flags that are reverently hung in sports arenas are clear symbols of civil religion (Snyder, 1972; Haberski Jr. & Nichols, 2017). Sports stadiums have almost become temples, where criticism is seen as sacrilege (Smith, 2007). Therefore, in American sports, there is an unwritten rule that the players should leave their political and social activism out of the sports arena (Peterson, 2009), implying that sports stadia have a free pass for social activism and critique. When players protest anyway, they can expect an overwhelmingly negative response from the media and the public (Coombs, Lambert, Cassilo & Humphries, 2019).

This is exactly what happened to Kaepernick. Right after the event, Drew Brees, also a football player, stated that he agreed with the importance of the issue of police brutality, but that kneeling was a sign disrespect to the American flag (Mather, 2019). The commissioner of the NFL, Roger Goodell, said he supports his players on wanting to change society for the better, but adds to that that the NFL strongly believes in patriotism (Mather, 2019), implying that Kaepernick does not. Donald Trump took it even further by saying that NFL players “should not be allowed to disrespect our Great American Flag (or Country) and should stand for the National Anthem. If not, you’re fired.” (Mather, 2019). There is a clear pattern seen in the negative responses that illustrates the perceived holiness of American sports and symbols: opponents claimed kneeling was disrespectful to the flag, veterans, and the American national overall.

The trap of civil religion

Even though opponents shared this view, Kaepernick himself actually indicated multiple times that he in no way wanted to insult his country: “I am not anti-American. (…) I love America. I love people. That is why I am doing this. I want to help make America better” (Mather, 2019). The specific act of kneeling, rather than sitting, was actually even designed by Kaepernick and teammate Reid to show respect towards veterans (Vasilogambros, 2016).

So why did the American public still think it was an insult? Sometimes, it seems as if citizens insist on showing excessive expressions of love for America, regardless of moral flaws in American society. This kind of response can be explained through the strong emphasis on paternalistic American values within the civil religion as Bellah imagined it (1967). These values might not be problematic on their own, but can inflame into a ‘trap’: a static, closed off sphere, if you want to somehow criticize or challenge these values. Bellah (1967) himself was actually afraid that the concept of civil religion could also create an ‘us versus them’ mentality by defining who is a good and who is a bad American; who ‘respects’ America and who does not (Britt, 2017). He stated that those who use civil religion to divide groups in society are not just blameless believers in civil religion, but “idolatrously worshippers of the state” (Bellah, 1967).

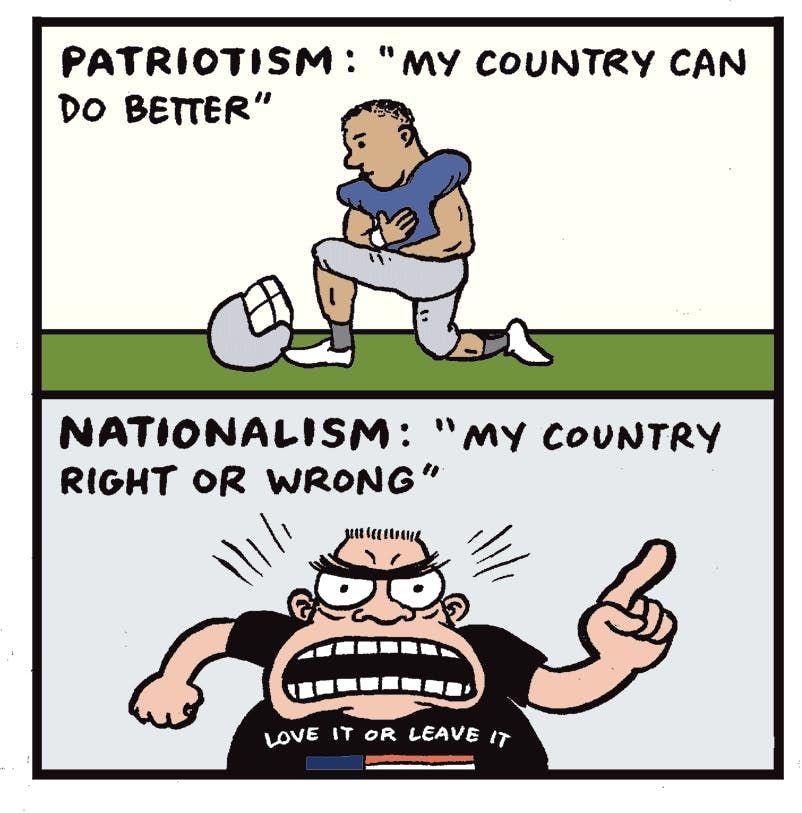

Some believers in civil religion are no longer patriotic, but have nationalistic tendencies; they are not just proud of America, but consider the state to be perfect and thus oppose any critique on it

Civil religion can be very beneficial to society, as it can strengthen shared values, bring love for fellow Americans (in the case of the USA), and improve cohesion (Lewin, Bick & Naor, 2016). However, the public responses to Kaepernick have shown that the civil religion that was envisioned by Bellah (1967) has gone from a set of beliefs that can strengthen shared values to blind worship of the state, regardless of the problems in society. Some believers in civil religion are no longer patriotic, but have nationalistic tendencies; they are not just proud of America, but consider the state to be perfect and thus oppose any critique on the state (de Figueiredo & Elkins, 2003). It has created a space that rejects anyone who dares to criticize the practice of American values and in result every protester, regardless of how valid the message may be, is dismissed as disrespectful.

The true meaning of patriotism

It thus all comes down to the approach of civil religion. As opposed to worshipping America no matter what , players are using a more active, rather than passive, form of civil religion that could drive America to achieve its ideals (Haberski Jr. & Nichols, 2017). Sport arenas would actually be a good place to discuss serious flaws in American society, as they are important for both white and black Americans. Allowing open discussions to happen would give Americans the chance to point out moral problems and align these with their values. Kaepernick’s team member, Eric Reid, perfectly explains this type of civil religion: “It should go without saying that I love my country and I’m proud to be American. Exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” (Haberski Jr. & Nichols, 2017).

I would argue that the act of kneeling is generally misunderstood, because opponents use a more nationalistic, rather than patriotic, approach. All Kaepernick was trying to do is point out important issues to his fellow Americans. Kneeling was never meant as an act of hate or disrespect, it was an act of ‘tough love’ patriotism (Haberski Jr. & Nichols, 2017). It should not be viewed as sacrilege against the nation, but as an act that challenges Americans to critically assess if the true American values they so love, are actually fulfilled in society. As mentioned before, the act of kneeling was designed to show respect to the flag, but also to recognize the nation’s failure to live up to its values and promises (Vasilogambros, 2016).

It is a fact that some American values are not yet completely achieved. Two values that are the core of American society are equality and autonomy (Kohls, 1984). All Americans should be free to control their own lives and should be deemed equal as others (Kohls, 1984). But despite these values, the USA has serious problems regarding racism and police brutality. The most recent case of police brutality is that of George Floyd, a black man killed by a white cop. The murder sparked great outrage all over the world, resulting in global ‘Black Lives Matter’ protests (BBC, 2020). The image of a white policeman kneeling minutes long on the neck of a black man is a horrible, yet powerful opposite image of Kaepernick peacefully kneeling for justice. Unfortunately, the case of George Floyd does not stand on its own. America knows countless examples of police brutality fuelled by racism; think of victims like Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and Eric Garner (LA Times, 2020). If one acknowledges this information, the message Kaepernick was trying to get across should be taken seriously.

The purpose of civil religion is listening to the voices of others, recognizing the flaws they are addressing and actively trying to solve them

Civil religion is meant to connect, to share values, to bond (Bellah, 1967). The purpose of civil religion is not to divide and judge. Showing love for your country is not just simply singing the national anthem and raising the American flag above your front door. It is also listening to the voices of others, recognizing the flaws they are addressing and trying your best to solve them. This is the prophetic function of civil religion. Loving your country and being critical of your country should not be two mutually exclusive things. After all, a true patriot would want their country to be in the best shape it could possibly be to reflect important national values.

In conclusion

The negative response of the American public to Kaepernick’s act of kneeling against racism and police brutality can clearly be understood through America’s passive sense of civil religion. Sports arenas have become sacred places, where any political and social activism is not appreciated (Smith 2007; Peterson 2009), which has led to the general idea that sports arenas should have a free pass from any social criticism. When Kaepernick decided to take a knee, even though he explained many times that he loved America, he received overwhelming negative comments from opponents claiming him to be hateful and disrespectful towards the American flag (Mather, 2019).

Americans should alter their idea of patriotism: this patriotism should not stop at hanging a flag above your door; it should include listening to the voices of the marginalized and taking their criticism seriously.

This type of response illustrates the trap that civil religion can create. The strong emphasis on paternalistic America values can result in a static, closed off sphere, rejecting anyone who criticizes or challenges the actual practice of the American values one cherishes so much (Bellah, 1967). Civil religion has gone from a set of beliefs that can strengthen shared values, to a blind worship of the state, that ignores moral issues in society. Unfortunately, moral issues are in fact blatantly present in American society. Even though equality and autonomy are important American values (Kohls, 1984), racism and police brutality are huge problems in American society (BBC, 2020; LA Times, 2020).

This is why players are adopting a new, active form of civil religion that uses the true meaning of patriotism and that could drive America to achieve its ideals (Haberski Jr. & Nichols, 2017). Kneeling should not be viewed as disrespectful, but rather as an act of ‘tough love’ patriotism (Haberski Jr. & Nichols, 2017), that challenges Americans to critically assess if their true American values are actually fulfilled in daily life. Americans should alter their idea of patriotism: this patriotism should not stop at hanging a flag above your door; it should include listening to the voices of the marginalized and taking their criticism seriously. Kaepernick's message is too important to ignore or shove aside as disrespectful, even if he chooses to express it on 'sacred' territory.

References

Bellah, R.N. (1967). Civil Religion in America. Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 96(1), 1-21.

Britt, B. (2017, 5 January). Taking a Knee as Critical Civil Religion. The University of Chicago Divinity School.

Coombs, D.S., Lambert, C.A., Cassilo, D. & Humphries, Z. (2019). Flag on the Play: Colin Kaepernick and the Protest Paradigm. Howard Journal of Communications.

Editorial: A very abbreviated history of police officers killing black people. (2020, 4 January). L.A. Times.

George Floyd death: US protests timeline. (2020, 4 June). BBC.

Haberski Jr., R., & Nichols, C. M. (2017, 1 October). Kneeling players are showing their country tough love, not disrespect. Washington Post.

Kohls, R.L. (1984). The Values Americans Live By. Fordham.edu.

Kosek, J.K. (2013). “Just a Bunch of Agitators”: Kneel-Ins and the Desegregation of Southern Churches. Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, 23(2), 232-261.

Lewin, E., Bick, E., & Naor, D. (2016). Comparative Perspective on Civil Religion, Nationalism, and Political Influence. USA: Information Science Reference.

Lüchau, P. (2009). Toward a Contextualized Concept of Civil Religion. Social Compass, 56(3), 371-386.

Mather, V. (2019, 20 November). A Timeline of Colin Kaepernick vs. the N.F.L. N.Y. Times.

Peterson, J. (2009). A ‘race’ for equality: Print media coverage of the 1968 Olympic protest by Tommie Smith and John Carlos. American Journalism, 26(2), 99–121.

Rogers, C. (1972). Sports, religion and politics: the renewal of an alliance. The Christian Century, 89, 392-394.

Smith, J.K.A. (2017, 23 November). The NFL’s Thanksgiving games are a spectacular display of America’s ‘God and country’ obsession. Washington Post.

Snyder, E.E. (1972). Athletic dressing room slogans as folklore: a means of socialization. International Review of Sport Sociology, 7, 89-102.

Yeboah, K. (2016, 6 september). A timeline of events since Colin Kaepernick’s national anthem protest. The Undefeated.