Aziz Ansari: Modern Public Intellectual?

What image comes to mind when we think of artists? For most of us, the preliminary sketch that springs to mind would be a lofty, disengaged artist whose visual/literary/performative oeuvres transcend the concerns of mortal men. However, as first impressions usually go, such an image of an aloof maestro fails to holistically grasp the repertoire of social positions artists can take up in their fields. Consider the works of visual artist Kenneth Tin-Kin Hung, or novelists George Orwell and Kathryn Stockett, in which rather than being transported to a realm of escapist fantasies, spectators are invited to contemplate existing conditions in our society. For example, Hung’s The Fast Supper (2011) reflects on obesity, the food industry, and consumer culture, while Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) comments on the surveillance state and Stockett’s The Help (2009) comments on racism.

The Fast Supper (2011)

Alternatively, if, following Jodi Kushins’ inclusion of Stephen Colbert's White House Correspondents' Dinner speech as an example of artistic contributions to political and social commentary (2006, p.2), we consider contemporary comedians performing artists, artists’ capacity to intervene in public debate becomes even more evident. As we take our daily dose of Trevor Noah or Samantha Bee, we are both entertained and, more importantly, intellectually challenged by these artists to take up more active roles as citizens.

Far from following the school of thought exemplified by “l'art pour l'art” (Art for art’s sake), as these artists become “spokespersons for multiple points of view and advocates for a critique of society” (Becker, 1997, p.18), they have seemingly assumed the role of public intellectual. Following this train of thought, in this article, I will explore the connection between contemporary comedians and the notion of the public intellectual, first by examining existing explorations of such interrelations and later via a case study of comedian Aziz Ansari's public persona.

Comedians as public intellectuals

While the conceptualization of comedians as public intellectuals has been explored in the academic field (see Belanger, 2017), one of the first formulations of this idea was an opinion piece in the Atlantic by Megan Garber. Titled “How comedians became public intellectuals'', Garber took female comedian Amy Schumer as a prime example, explaining that comedians are increasingly able to assert considerable influence within the public sphere not only via social media but also by establishing a constant information cycle between the comedian, journalistic gatekeepers, and ordinary viewers in the hybrid media system.

When comedy broke past “angsty and possibly drug-addled white guys making jokes about their needy girlfriends and airplane food” and began to embrace the voices of women and minorities, this “newfound inclusion” came with an increase in subverting norms and highlighting “questions about power dynamics and privilege and cultural authority” (Garber, 2015). Garber contended that recent comedians have assumed the role of public intellectuals on two grounds, namely that these modern humorists have received a growing amount of “mass attention” (public) and that they have begun addressing social issues and incorporating “moral messaging” (intellectual) in their content (2015).

Contesting comedians as public intellectuals

That being said, the concept of modern comedians as public intellectuals is not without its discontents. One noteworthy contestation was been formulated by Elizabeth Bruenig in a New Republic article titled “Comedians are funny, not public intellectuals”. In the piece, the author argued against Garber’s assertion that the increasingly subversive nature of comedy enables fruitful explorations and interrogations of modern society.

Bruenig argued that while comedians indeed possess the capacity to question established power dynamics, one has to bear in mind that since our humorists are operating within a commercialized media system, they tend to only “tease at genuine subversion, while making commonly held views” (2015). In other words, contrary to Garber, Bruenig believes that, at the end of the day, modern comedians merely utilize the risk-free and profitable tactic of superficial subversion so as to generate guaranteed laughter and consistent digital labour from their audience.

The Public Intellectual

In her book Writers as Public Intellectuals, Odile Heynders lays out a preliminary blueprint for the public intellectual:

“The public intellectual intervenes in public debate and proclaims a controversial and committed and sometimes compromised stance from a sideline position. He has critical knowledge and ideas, stimulates a discussion and offers alternative scenarios in regard to topics of political, social, ethical nature, thus addressing non-specialist audiences on matters of general concern. Public intellectual intervention can take many different forms ranging from speeches and lectures to books, articles, manifestos, documentaries, television programmes and blogs and tweets on the Internet. Today’s public intellectual operates in a media-saturated society and has to be visible in order to communicate to a broad public”(Heynders, 2016, p.3).

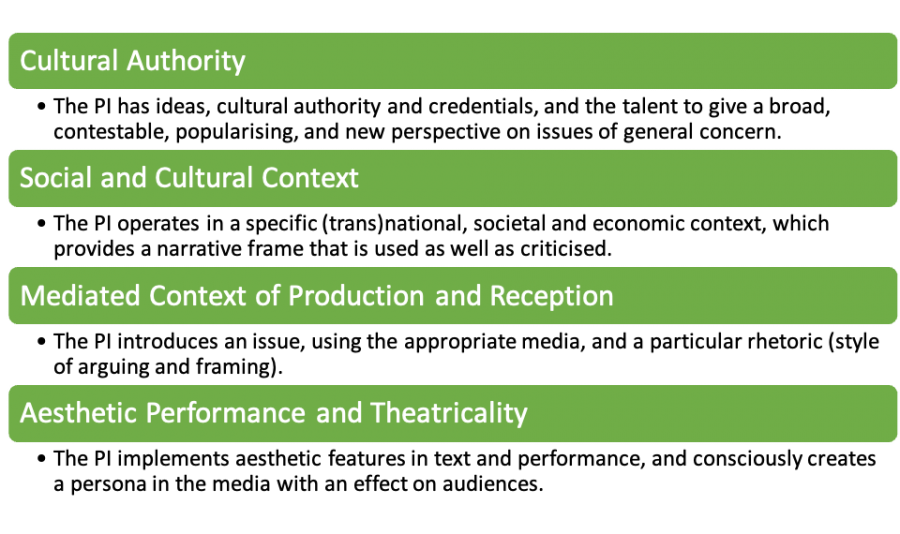

While Heynders’ work mainly focuses on literary writers who constructs the posture of the public intellectual through a variety of media performances, the detailed conceptualisation of the persona nonetheless provides us valuable insights if we wish to apply such a framework to other fields of interest. Additionally Heynders has laid out a four-level heuristic model for researching public intellectuals:

Heuristic four-level scheme for researching public intellectuals, excerpted from Heynders (2016, p.21)

This four-level scheme provides a foundation on which an in-depth analysis of the construction of a public intellectual persona could be based. For my investigation of Aziz Ansari, I will mainly focus on his comedy sets and literary works and the specific rhetorical style he uses in each medium to demonstrate his engagement with the first and third level of the model (cultural authority and mediated context of production and reception).

The Comedian-Public Intellectual Debate

Before moving forward to our case study, let us circle back to the Garber vs. Bruenig debate. While Bruenig’s criticism is undoubtedly valid, if we take Heynders’ (2016) conceptualisation of the public intellectual into account, I believe there are two points of consideration to bear in mind. On the one hand, although modern comedians are only willing to be subversive insofar as it financially benefits them, comedy and humor could serve as an effective spark for necessary discussions in the public sphere, a point that Garber also made in her essay. On the other hand, as Heynders’ definition of public intellectuals (2016, p.3) suggests, public intellectual interpositions could manifest themselves in a variety of forms, including, in the case of our humorists, stand-up comedy specials.

The public intellectual is, all in all, a posture constructed through a complex negotiation between multiple social actors across several mediums. As such, any particular comedian’s capacity to function as a public intellectual should not solely be based on their position in the comedy field or the specific performative style that they employ, but rather should take into consideration the comedian’s repertoire of diverse media performances.

Aziz Ansari

Let us delve into our case study: Aziz Ansari is an Indian-American comedian and actor who began his career in 2000. While Ansari tackles several topics of public interest, such as religion and racism, his comedy routine mainly focuses on the peculiarity of modern romance. As an actor, he is mostly known for his role on the NBC comedy series Parks and Recreation and the Netflix series Master of None (Czajkowski, 2015).

Trivialization of the public sphere

First and foremost, aside from the general argument against comedians as public intellectuals, what might be problematic for the subject of this study is that Ansari’s main issue of concern, i.e., romantic relationships in the modern era, is one that is not traditionally considered a matter deserving of discussion in the public sphere. Rather, in the eyes of Habermas or Arendt, the public sphere should be a domain where citizens engage in critical rational debates on state affairs that “put the state in touch of the needs of society” (Habermas, 1991, p.31) or conversations on issues that “transcends the lifespan of mortal men” (Arendt, 1958, p.55). Topics such as the family and household would be relegated to the private sphere, a realm where what one does “remains without significance and consequence to others, and what matters to him is without interest to other people” (Arendt, 1958, p.58).

Furthermore, for these scholars, the fact that domestic affairs and romantic relationships are being publicly discussed points to a fundamental structural problem of the contemporary public sphere, that is, these “trivialities” have driven attention away from “serious public affairs” (McKee, 2004, p.33). Seen from this perspective, examining Ansari’s posture through the lens of the public intellectual seems insubstantial, for his main concern is one that should be cast out from the exact site a public intellectual operates, i.e., the public sphere.

Nonetheless, other scholars have also argued that trivialities likewise deserve attention in the public sphere. Most notably, Alan McKee offered four arguments for bringing the private to the public in his book The Public Sphere: An Introduction, two of which are especially relevant within the context of this study. Firstly, to the extent that domestic issues and women are traditionally kept in the private realm, there exists an absence of women’s voices. As such, by publicizing domestic issues, not only the women’s voices could be heard but a proper mechanism against injustice within the private realm could be established (McKee, 2004, p.47).

Secondly, it should be noted that domestic concerns are not trivial: issues of “relationships, child-rearing, housework, and sexuality were in fact important parts of human society and has to be recognised as such”. For this reason, publicising matters previously relegated to the private realm is of great significance. Just as questioning state affairs could lead to needed adjustments in the political field, so could being critical of private issues change the domestic scene and our personal lives for the better (McKee, 2004, p.47). Seen from this point of view then, Aziz Ansari could be fittingly discussed as a public intellectual in his endeavour to explore modern romance.

Modern public intellectuals: An investigation

Using Heynders’ (2016) framework on public intellectuals, I will examine Aziz Ansari’s overall construction of his public persona, as observed from two of his selected media performances: his comedy specials available on Netflix (Aziz Ansari | Buried Alive, Aziz Ansari Live at Madison Square Garden, & Aziz Ansari: Right Now) and his literary work (Modern Romance: An Investigation).

Comedy Specials

As his original site of operation, Ansari’s comedy specials serve not only as showcases for his talent but also offer us a preliminary glimpse into his conception of modern romance and marriage.

First and foremost, it is telling that in the two comedy specials Aziz Ansari chose to wear finely-tailored suits, creating a twofold impression: on the one hand, the suits signify his established authority in the field and is emblematic of his professionalism; on the other hand, the formal apparel suggests the image of a gentleman, which connects thematically to his routine and creates a manufactured credibility on which he can express his ideas on modern romance.

Aziz Ansari, the Western gunslinger

Ansari also embraces theatricality to its fullest. In the introductory sequence for the 2015 comedy special Aziz Ansari Live at Madison Square Garden, Ansari's silhouette emerges against a backdrop of a rising sun, accompanied by a western soundtrack. The image resembles a western gunslinger - through this romanticized scene, Ansari draws a parallel between his role as a modern comedian-intellectual with the iconic western dramatis personae.

Aziz Ansari | Buried Alive

In this 2013 comedy special, the first few minutes of the comedian’s routine on online dating exemplifies how Ansari formulates his arguments in his sets. In this bit, the comedian sets up this routine with an initial inquiry:

“Where do you meet this person? I think it’s very hard to meet someone you really connect with, that you really feel a deep connection with. I think that’s hard. I don’t think those people just come around all the time”(Ansari, 2013).

Here Ansari introduces a rhetorical question which leads us to the main event, i.e., his observations vis-à-vis online dating. However, he first takes a detour to lay out the contemporary online dating milieu:

“I think it’s a very special thing. And I think it’s very hard to find, especially nowadays. I mean, yes, there’s great people around, but, man, there is so much riffraff out there right now. The percentage of riffraff has never been higher. It’s very high” (Ansari, 2013).

To illustrate his argument that there has been an increase in the amount of unsavory people in modern the dating scene, the comedian compares different generations to different fonts:

“Maybe I’m romanticizing the past, but you think about like older generations, you know, people in their 20s– 60s, whatever. You just imagine a different vibe. You know, imagine men wearing nice suits, women are dressed all nice, everyone’s speaking properly– just a classier vibe. Like if those generations could be a font they would be 'Times New Roman'. I look at my generation… We’re fucking Comic Sans. You can’t take us seriously. We’re Comic Sans. People that are single and out there, you know what I’m talking about? You go out with people sometimes and you’re just like, 'What, you’re a person?!' 'Hold up. You’re a person?'” (Ansari, 2013).

Following his exposition of modern times, Ansari delves into the meat of his routine: online dating. Drawing on a friend's anecdote, he says,

“I have a friend, he met his wife on one of those sites and I asked him, I was like, ‘So, what’d you search?’ ‘Cause that’s weirdly romantic. He types in this phrase, all these algorithms and things come together, this woman’s face comes up, he clicks it… that becomes the woman he spends the rest of his life with. So I asked him, ‘What’d you search?’ And he goes, ‘Jewish and my zip code'” (Ansari, 2013).

Here Ansari set up an antithesis that creates a humorous contrast between his preconceptions and the reality of online dating. His delivery of the punchline, “Jewish and my zip code” underscores this peculiarity, using an unjustifiably confident voice to indicate his friend’s ignorance of the idiosyncrasies of online dating. Finally, in the concluding note of this initial bit, he turns to an analogy between how his friend found the love of his life and how he tracked down a fast food restaurant:

“Jewish and my zip– I found a Wendy’s that way a few weeks ago! I typed Wendy’s and my zip code then I got some nuggets, he got a wife the exact same way!” (Ansari, 2013).

Poster for Aziz Ansari | Buried Alive

Aziz Ansari Live at Madison Square Garden

Another technique Ansari often utilizes in his comedy sets is improvised crowd work, which is on full display in his 2015 comedy special. After lamenting the difficulties of texting in the dating scene and modern daters' suboptimal rejection methods, the comedian invites the audience to share their own text histories:

“All right, so how long ago did you meet this person? Uh, September 2nd. September 2nd. Okay, so let’s see what happened, okay? So… he sends the first message. He sends it Tuesday, September 2nd at 11:26 p.m. Odd time to send a first message. He says, ‘Hey, Ashley, dot-dot-dot, it’s Chris.’ He said his last name, but I don’t wanna repeat it in case he gets murdered. ‘Hey, Ashley, dot-dot-dot.’ I like that, ‘dot-dot-dot.’ ‘Hey, Ashley…’ ‘It’s Chris’ (in a charming voice)” (Ansari, 2015).

In this particular crowd work, Ansari uses two interconnected strategies to comedic effect. First, Ansari organically implements ad-lib responses based on the text message details (odd time to send the initial message, Chris mentioning his last name, & the “dot-dot-dot”).

While all of his reactions to the material evoke laughter from the crowd, it is the last observation, the “dot-dot-dot”, that Ansari uses in the following dramatic scene work to engage the audience. He employs an exaggeratedly seductive voice to narrate the text messages from Chris, which serves to dramatize the character. This conception is immediately shattered, however,

“It was nice to hang– It was– It started so smooth. ‘Hey, Ashley, dot-dot-dot, it’s Chris.’ And then he goes, ‘It was nice to hanging with you…’ (in a goofy voice). Chris, no! Proofread! ‘It was nice to–’" His voice changes for the rest of the bit now: "‘Hey, Ashley, it’s Chris’ (in a charming voice). Now it’s, ‘Hey, Ashley, it’s Chris. It was nice to hanging with you at BM. Hope you’re recovering well. Let’s grab a coffee sometime’ (in a goofy voice)" (Ansari, 2015).

Upon noticing the grammatical error in Chris’ text message, the comedian immediately changes tone. Instead of continuing with the charismatic voice, he opts for a goofy nasal voice, painting the picture of an unintelligent, unconfident man.

This shift in voice is highlighted via an antithetical structure, in which the contrast between the charming, confident Chris and the goofy, unappealing Chris is displayed. This sequence has two effects: one, it shows that grammatically incorrect text messages during romantic pursuit can lead to disastrous consequences; two, the scene is a realistic commentary on texting conventions in the modern dating world.

As Heynders (2016) has suggested, the public intellectual must possess two forms of cultural capital so as to position themselves in front of the public and take an alternative stance on societal issues. On the one hand, in order for public intellectuals to assert their place in the public sphere, they must have already gained considerable prestige in their original field. Whether such prestige is based on “an (academic) education or specialisation” or “artistic achievements,” public intellectuals’ interventions are grounded in this “cultural authority”.

On the other hand, public intellectuals, by the very inclusion of the word “public”, must negotiate their public presences in front of a broader public. This means that it is also necessary for public intellectuals to possess “the talent to give a broad, contestable, popularising, and new perspective on issues of public interests” (p.21).

In line with Heynders’, Ansari's commanding theatricality, masterful use of rhetorical devices, and crowd work serve as demonstrations of not only his cultural authority but also his talent in publicizing his ideas in a digestible and relatable manner. Both of these function as a foundation for Ansari’s other media interventions within the public sphere.

Aziz Ansari Live at Madison Square Garden

Modern Romance: An Investigation

Public intellectuals can come from a variety of backgrounds, but they must “write and put their ideas into words” in order to qualify as such (Heynders, 2016, p.22). In the case of Aziz Ansari, we can find the literary manifestation of his ideas in his 2015 work Modern Romance: An investigation.

The most illustrative example of Ansari’s thoughts on modern romance comes from the third chapter of Modern Romance, titled Online Dating. In this segment, similar to his comedy specials, Ansari introduces the topic by offering his personal opinions on online dating.

While Ansari himself feels hesitant to try online dating given he's a public figure, he does acknowledge its prevalence in the modern dating scene and thinks it is a “beautiful and fascinating thing.” He illustrates this sentiment with the aforementioned “Jewish and my zip code” story, as seen from his 2013 comedy special:

“It’s an amazing series of events: He types in this phrase, all these random factors and algorithms come together, this woman’s face comes up, he clicks it, he sends a message, and then eventually that woman becomes the person he spends the rest of his life with. Now they’re married and have a kid. A life. A new life was created because one moment, years ago, he decided to type ‘Jewish 90046’† and hit ‘enter’” (Ansari, 2015, p.71).

Ansari then charts out a comprehensive history of dating services, from classified advertisements, to video dating, to online dating services. This historical overview is often accompanied by individual case studies, in which the comedian examines pieces of texts from these antiquated services. It is also interesting to note that the tone of the comedian’s analysis resembles his comedy act rather than the detached style of academic writing:

“'SEEKING ADVENTURE?? Divorced Jewish male, 49, enjoys sailing, hiking, biking, camping, travel, art, music, French and Spanish. Seeking a woman who’s looking for a long-term relationship and who shares some of these interests. Be bold—call right now! Chicago Reader Box XXXXX.'

There’s a lot in this ad that will look familiar to today’s online daters. Ed gives his status, religion, age, and personal interests. We get a sense that he’s pretty cosmopolitan, and there’s even a promise of adventure if we dare to be bold. (Nice move, Ed!)" (Ansari, 2015, p.74).

After sketching out the history of dating services, Ansari begins his own analysis of online dating. In the section Online Dating Today, he changes style to that of the detached intellectual, referring to the work of Cacioppo and Rosenfeld, two relevant academic scholars. This disinterestedness reminiscent of academic writing can also be observed in the comedian’s acknowledgement and response to criticisms of Cacioppo’s statistics (2013) on how Americans meet their spouses:

“Cacioppo’s findings are so shocking that many pundits questioned their validity, or else argued that the researchers were biased because they were funded by an online dating company. But the truth is that the findings are largely consistent with those of Stanford University sociologist Michael Rosenfeld, who has done more than anyone to document the rise of Internet dating and the decline of just about every other way of connecting. His survey, ‘How Couples Meet and Stay Together,’ is a nationally representative study of four thousand Americans, 75 percent married or in a romantic relationship and 25 percent single. It asked adults of all ages how they met their romantic partners, and since some of the respondents were older, the survey allows us to see how things varied among different periods” (Ansari, 2015, p.79).

That being said, Ansari also occasionally deviates from this intellectual position, instead choosing a more playful voice, bringing to audiences’ mind his background as a comedian:

“Another popular way partners found each other in 1990 was when a man would yell something to the effect of ‘Hey, girl, come back here with that fine butt that’s in them fly-ass acid-washed jeans and let me take you to a Spin Doctors/Better Than Ezra concert.’ The woman, flattered by the attention and the opportunity to see one of the preeminent musical acts of the era, would quickly oblige. This is how roughly 6 percent of couples formed. To be clear, this is just a guess on my part and has nothing to do with Mr. Rosenfeld’s research” (Ansari, 2015, p.81).

This contrast lays bare the tension inherent within the model of public intellectuals. In offering criticism and alternative visions public intellectuals must position themselves as detached, taking an “analytical or comparative perspective towards an issue, distancing oneself from the ongoing debate and as such establish a corrective view” (Collini, 2009, p.61, cited in Heynders, 2016, p.22). On the other hand, since public intellectuals have to spread “communicable knowledge” to a broad public, they must translate their works into “insights that the general public can understand” (Heynders, 2016, p.22).

In other words, the position of the public intellectual, by its very definition, is a contradictory one: while taking an objective stance towards a subject is necessary in the formulation of a noncomforming opinion (intellectual), translating a concept for public consumption (public) implies that such an intellectual position is at times compromised in order to popularize ideas.

Ansari fails to commit to a purely analytical intellectual position, instead resorting to playful commentaries on the examined materials, whether that be statistics or case studies. This failure, following Heynders (2016), may be an intentional one made in an effort to reach a wider public.

Cover of Modern Romance: An Investigation

The Babe Story

So far our investigation of Aziz Ansari’s persona has focused on his media performances, namely his comedy specials and writing. However, as Jérôme Meizoz has suggested, a persona, or posture, is “not uniquely an author’s own construction, but an interactive process: the image is co-constructed by the author and various mediators (journalists, criticism, biographies) serving the reading public” (2010, p.85).

Similarly, Heynders has also argued that the role of the public intellectual is not merely “funded on cultural authority and autonomy or on rational argumentation and independence”, but influenced by a “vertical engagement with the public” (Baert and Shipman, 2013, p.44, cited in Heynders, 2016, p.12). In other words, a proper examination of Ansari’s persona within the public intellectual framework needs to bear in mind not only his various media performances but also whether the public recognises him as such.

In Ansari's case, we are able to observe an event that impacted his public reception and in turn compromised his position as public intellectual. On 13 January, 2018, Katie Way published an exposé on Babe.net titled “I went on a date with Aziz Ansari. It turned into the worst night of my life.” In the piece, the writer details Ansari’s alleged sexual misconduct against a woman pseudonymously referred to as Grace. According to Grace, after meeting at the 2017 Emmy Awards after-party, the two went on a date on 25 September, 2017. On the date, the comedian, despite Grace’s use of “verbal and non-verbal cues to indicate how uncomfortable and distressed she was”, pressed her into having intercourse with him (Way, 2018).

Considering that Ansari has been an outspoken figure on feminism and has positioned himself as a public intellectual on modern romance, the incident directly undermines the legitimacy of his role in the public sphere. It is important to note that such a perception is similarly highlighted in several other journalistic and opinion pieces on the controversial revelation (see Framke, 2018; Stefansky, 2018; & Silman, 2018).

Two days after Way’s article was published, Ansari issued an official statement:

“In September of last year, I met a woman at a party. We exchanged numbers. We texted back and forth and eventually went on a date. We went out to dinner, and afterwards we ended up engaging in sexual activity, which by all indications was completely consensual.

The next day, I got a text from her saying that although ‘it may have seemed okay,’ upon further reflection, she felt uncomfortable. It was true that everything did seem okay to me, so when I heard that it was not the case for her, I was surprised and concerned. I took her words to heart and responded privately after taking the time to process what she had said.

I continue to support the movement that is happening in our culture. It is necessary and long overdue” (Ansari, 2018, cited in Plaugic, 2018).

Almost a year after Way’s exposé, Ansari released a new comedy special on Netflix titled “Aziz Ansari: Right Now,” in which the comedian publicly addresses the controversy. There are two main points of consideration in this special. First, unlike his previous comedy performances, the comedian’s choice of attire is rather casual: a Metallica t-shirt and a pair of jeans instead of a finely tailored suit, telegraphing sincerity and authenticity.

Second, the comedy set is thematically threaded together by Ansari’s reflections on Grace’s allegations. One of the routines that exemplifies this theme comes at the midpoint of this special, which focuses on a story about visiting his grandmother who is suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. After detailing the interaction between him and his grandmother during his visit, the comedian offers this piece of reflection:

“When you’re younger and you meet people that old, you only knew them in the deteriorated state, right? Like, if you ever met your great-grandma, the first time you met her, she was like, ‘Aah!’ Uh, ‘Hi, Great-grandma Carol.’ You didn’t know her when she was jumping rope or whatever. Like, you only knew her as this Star Wars villain-type person. But now, you see that change. It’s very scary. ‘Cause you realize that’s coming for us all, right? It’s coming for us. It’s coming for our parents. That’s when it gets scary, right? You start thinking about your folks. I’m very lucky, both of my parents are still alive and well, still have it all up here. And I completely take it for granted. I don’t call ’em enough. I don’t see ’em enough. You see your folks enough? How often do you see them? What, two or three times a year? What have they got left? Maybe 20 years? That’s… 60 more times you get to see ’em. That’s it. Sixty more times. Sixty more hangs. Are you making the most of these hangs? Are you creating cherished memories?” (Ansari, 2019).

This reflection serves as a callback for the final moments of this special, in which the comedian contemplates his life after the controversy. Here Ansari clues the audience in on the main theme of this comedy special: the realization that his career could end at any given moment. In light of this he has become more appreciative and intends to live in the moment. The concluding remark is sincere and intimate, earning a standing ovation from the audience:

“I didn’t really think about what it means that all you guys came out … And it means the world to me, ’cause… I saw the world… where I don’t ever get to do this again. And… it almost felt like I’d died. In a way… I did. That old Aziz who said, ‘Oh, treat yo’ self,’ whatever, he’s dead. But I’m glad… ’cause that guy… was always looking forward… to whatever was next. ‘Oh, am I gonna do another tour? Am I gonna do another season of the show?’ Blah, blah, blah. I don’t think that way anymore. ‘Cause I’ve realized… it’s all ephemeral. All that stuff… it can just go away… like this… And all we really have… is the moment we’re in… and the people we’re with.

Now, I talked about my grandma earlier, and it was sad. But what I didn’t tell you was the whole time when I was with her, she was smiling, she was laughing, she was there with me. She was present in a way no other people I’ve been around recently have been. I’ve tried to take that with me. And Granny, my grandma, doesn’t have much choice in this matter. But I do. And that’s how I choose to live, in the moment I’m in with the people I’m with. And right now, this is our moment, right? … So, you know what? Why don’t we all just take it in for just a second? And on that, I’ll say good night, and thank you very, very much. Thank you” (Ansari, 2019).

What might be observed here is Ansari’s reactionary stance towards an incident that could potentially damage his position as a public intellectual. The controversy directly compromised his cultural authority as a prestigious comedian with keen insights on modern romance; as such, the comedian employs an alternative, modest and sincere tone in response to public criticisms.

On the one hand, one needs to bear in mind that while the overall tone of the comedian’s performance is sincere and authentic, such stance in itself entails theatricality and use of rhetorical strategies. This again points to Ansari’s capacity to express his ideas in a broadly relatable way - a previously established faculty of the public intellectual. On the other hand, in line with both Meizoz and Heynders, the information cycle between journalists and the public figure illustrates the intertwining of the conscious construction of a persona and potential contestations from mediators in the public sphere, leading to a recalibration of how the public intellectual asserts their place in a given field.

Aziz Ansari: Right Now

Aziz Ansari and the Public Intellctual

This article examined the interrelation between comedians and the public intellectual theoretical model. While previous discussions have fixated on whether comedians can be discussed as public intellectuals based their comedy performances, I have instead opted to investigate this from a multimedia perspective by taking into account both comedy routines and Ansari's literary works. I have identified three main points of consideration. First, in terms of his comedy sets, Ansari uses theatricality and rhetorical strategies to the fullest, bolstering his cultural authority within the field (through which he can intervene in public debate) but displaying his talents in communicating ideas in an easily digestible manner (a faculty essential for public intellectuals).

Second, Ansari’s literary work, Modern Romance: An Investigation, demonstrates a tension commonly found in the public intellectual model. While intellectuals could comfortably assert a detached position on which to base their objective analysis, public intellectuals often fail to completely commit to a disinterested position in order to comprehensively address the broader public.

Last but not least, following Meizoz (2010), we dove into the Babe exposé. The controversy led to public contestations of Aziz Ansari’s established cultural authority through which he had been able to address a particular issue, i.e., modern romance. Such dissent regarding the legitimacy of his role in the public sphere in turn resulted in a shift in Ansari’s strategies in the construction of his public image.

All things considered, it might be difficult to reach a decisive conclusion with regard to whether or not Aziz Ansari could be viewed as a public intellectual. As our examination of the Garber vs. Bruenig debate revealed, framing the question as "either-or" invokes a dichotomy that fails to holistically capture the creation of a public image. Nonetheless, the public intellectual model serves well as a heuristic framework for shedding light on the complex negotiations inherent in establishing Aziz Ansari’s public persona.

References

Ansari, A. (2013). Aziz Ansari | Buried alive. Netflix.

Ansari, A. (2015). Aziz Ansari Live at Madison Square Garden. Netflix.

Ansari, A. (2019). Aziz Ansari: Right Now. Netflix.

Ansari, A. (2015). Modern romance: An investigation. London, England: Penguin Group.

Arendt, H. (1958). The human condition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Baert, P. & Shipman, A. (2013). The rise of the embedded intellectual: New forms of public engagement and critique. In P. Thijssen, W. Weyns, C. Timmerman, & S. Mels (Eds.), New Public Spheres: Recontextualising the Intellectual. Farnham, England: Ashgate.

Becker, C. (1997). The artist as public intellectual. In H.A. Giroux & P. Shannon (Eds.), Education and Cultural Studies: Toward a Performative Practice. London, England: Routledge.

Bruenig, E. (2015). Comedians are funny, not public intellectuals. The New Republic.

Collini, S. (2009). Absent minds: Intellectuals in Britain. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Czajkowski, E. (2015). The evolution of Aziz Ansari. Vulture.

Garber, M. (2015). How comedians became public intellectuals. The Atlantic.

Habermas, J. (1991). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of Bourgeois society. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press.

Heynders, O. (2016). Writers as public intellectuals. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kushins, J. (2006). Recognising artists as public intellectuals: A pedagogical imperative. CultureWork, 10 (2), pp. 1-5.

McKee, A. (2004). The public sphere: An introduction. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Meizoz, J. (2010). Modern Posterities of Posture. Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In G.J. Dorleijn, R. Grüttemeier, & L.K. Altes (Eds.), Authorship Revisited. Conceptions of Authorship around 1900 and 2000. Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press.

Plaugic, L. (2018). Aziz Ansari responds to allegations of sexual misconduct. The Verge.

Way, K. (2018). I went on a date with Aziz Ansari. It turned into the worst night of my life. Babe.