BIOR: local vs global voices in a case of cultural appropriation

In a globalized world where information and culture are easily accessible, the issue of cultural appropriation has become increasingly prevalent. Cultural appropriation can be defined as the act of taking elements of a culture that belong to a minority group and using them without permission or understanding of their significance. The fashion industry is no exception to this issue, with many high-end brands appropriating traditional clothing and designs from various cultures to sell as trendy fashion pieces. One example of this is the controversy surrounding Dior's "Sauvage" campaign, which featured Native American imagery and was widely criticized for cultural appropriation. However, the story between Dior and Bihor, a traditional Romanian region, also sheds light on the complexities of cultural appropriation and the importance of understanding the cultural context behind these practices. This essay will explore the concept of cultural appropriation in a globalized world, examining its various forms, its impact on marginalized communities, and the power dynamics between local and global voices.

Cultural appropriation in a globalized world

The notion of cultural appropriation evokes, or at least suggests, the existence of an articulated form of resistance against cultural erosion. The definition of the term also implies a unidirectional process where a dominant majority exploits a minority culture. According to Rogers (2006), cultural appropriation represents the use of one culture’s symbols, artifacts, genres, rituals, or technologies by members of another culture, regardless of intent, ethics, function, or outcome. Ziff and Rao (1997) offer a slightly different definition, that of “ the taking – from a culture that is not one’s own – of intellectual property, cultural expression or artifacts, history and way of knowledge […] and profiting at the expense of the people and that culture" (Ziff and Rao 1997: 24). Cultural appropriation is not just a term that conceptualizes cultural exchange, cultural dominance, cultural exploitation, or transculturation (Rogers 2006). From a historical perspective, it’s also part of postcolonial discourse - an ideological response to both colonialism and neocolonialism. Built on notions surrounding cultural memory, heritage, and both national and cultural identity, cultural appropriation is a term that encompasses both an ideology and a “practice.”

As society changed, so did our understanding of culture, identity, and diversity. Globalization, as we experience it today, brought forward new spaces that were previously in the margins, and with that new identities, new cultural artifacts, new linguistic repertoires, and so on. There is also the element of mobility; people, languages, cultural artifacts, etc. are highly mobile in both real and ‘virtual’ spaces. All these societal changes plus the emergence of new, multimodal forms of communication bring forward a series of challenges when considering if an act of cultural borrowing is, in fact, cultural appropriation. One could argue that cultural appropriation has become highly individualized and that not everybody that participates in cultural borrowing is, in fact, a colonist in disguise.

When there is an ideology, there is also an audience. With new channels of communication, like social media, cultural appropriation has been the ‘talk of the town’ by addressing it in correlation with different practices. Very often, these practices revolve around notions like fashion, lifestyle, and art.

Fashion and identity display

Clothes are cultural goods because, as artifacts, they create behavior through their capacity to impose social identities and empower people to assert these latent social identities. During the 19th century, individuals competed for social distinction and cultural capital within social classes, basing their judgments in terms of cultural goods according to class-based standards of taste and manner. The clothes one wore were a reflection of their social class (Crane, 2009).

However, contemporary fashion is more ambiguous and multifaceted; there is an abundance of fashion styles and personal appearances. Instead of class cultures, there is a fragmentation of interests within social classes, in terms of individual and particular interests. The variety of choices in lifestyles available liberates the individual from the traditional sense of fashion and helps with creating a meaningful self-identity (Giddens, 1991). In our current society, consumers use various fashion discourses to create self-defining social distinctions, social boundaries, and personal narratives. They also use these discourses to understand their relationship with consumer culture, history, and to contest conventional social categories.

The meaning of cultural products depends on the relationship between creators and the public and between managers and the market. In the twentieth century, fashion organizations have been transformed as “their potential publics have expanded from local to national and from national to global” (Crane, 2009: 15).

Cultural appropriation in fashion

In the past years, more and more fashion brands have been accused of cultural appropriation, including both mass-market brands and prestigious brands that have a long history in fashion. Discussions about cultural borrowing in fashion are not limited to the design of the clothes; they also extend to accessories, culturally specific hairstyles, and runway shows. In 2018, social media called out Dior for using a white model to advertise an outfit that was inspired by Mexican heritage. In this case, although Dior claims to celebrate Mexican culture, the discourse is constructed around a more complex problem, the lack of ethnic diversity, and ethnic misrepresentations in fashion and in other spaces like mainstream media. Like in many other cases, this act of cultural appropriation takes place between a dominant culture (western imperialist culture) and an ethnic minority from a colonized society. On the other hand, with globalization in other margins than the one previously established, cultural borrowing does not limit to racially oppressed groups or formerly colonized cultures. Of course, these new groups have different sensibilities and attitudes based on their identity and ideologies.

#BihornotDior: a fight from the margin to the center

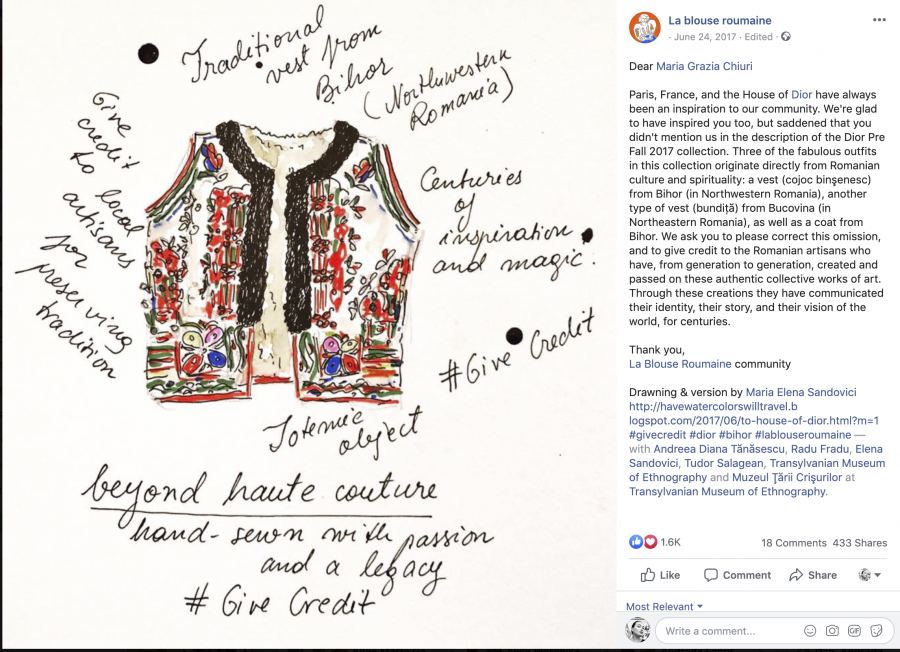

The story between Bihor and Dior starts similarly to other cases of cultural borrowing. A community called La blouse roumaine calls out Dior, on social media, for using traditional Romanian clothing as a source of inspiration for their 2017 pre-fall collection. Moreover, they accuse the renowned fashion house of plagiarizing (making an almost identical copy) of a traditional jacket.

A drawing of the Beius Jacket in a post by La BLouse Roumaine.

La blouse roumaine describes itself to be an online community that promotes the traditional flex shirt with the common goal of creating a collective cultural brand that will promote the image of Romania internationally. “This way, we can transmit to future generations the art, traditional knowledge, and the soul heritage left by generations of people who lived in the Romanian space.” Another objective of this movement is campaigning against cultural appropriation without giving credit to the original culture (“ GIVE CREDIT” campaign).

Wang and Kroon (2016) explain that heritage, in a globalized world, is something chronotopically niched where the authenticity claims are complex processes that involve semiotic maneuvering so it can be recognizable for multiple centers and scales. For those who find themself in the periphery, reclaiming authenticity over certain grounds, even if symbolically like #bihornotdior, can create a sense of autonomy in identity-making. This happens especially when the relation center-periphery is locally contested and reframed.

Caption writes: What does the Valentino 2015 and Dior 2017 have in common? 1. Romanian inspiration 2. Same artistic director

There are multiple voices that create different types of discourse around #bihornotdior. While La blouse roumaine acts as a voice for cultural recognition and cultural preservation, other mediums bring forward the economical aspect of cultural appropriation. In this sense, a collaboration between a PR company and a Romanian fashion magazine creates a direct link between a small community of artisanal craftsmanship from Bihor, Romania, and the rest of the world. Thus, Bihor Couture becomes a statement of globalization in the margins. Starting as a branding campaign, Bihor Couture doesn’t represent just a place for the local group to sell their products, it also acts as a space where ideologies are being presented and identities are being asserted. For example, their video campaign is a form of presenting the local identity in contrast with globalized identity by showing the local community reacting to Dior’s design and commenting on the side of it. The final image is that of a community in need of a voice and a platform in order to preserve their authenticity and traditional practices; a counter-movement, that is not free of politics.

Local vs. global voices

What we are witnessing here is the issue of voice: the way in which people manage to make themselves understood (or fail to do so) (Blommaert, 2005). According to Blommaert (2005), voice is about function, which is affected by societal values attributed to language. Therefore, differences in language can be seen as differences in social values: it is through language differences that boundaries of power, status, and role in social life are created and maintained (Gumpers, 1982: 6-7). In the context of globalization, we see that the mobility of voices – semiotic signs – is often attributed to prestigious ‘world languages’ and denied to lower-ranking languages at the margins (Blommaert, 2005: 84).

There are multiple voices present in our case, starting with the voice of the local Romanian community, wearing traditional handmade clothing as part of its identity. What follows in 2017 is Dior – a global fashion house – using the Romanian jacket as part of “reimaging a bohemian impulse” with their couture collection and aims to represent the multiculturalism in Paris that “gives the city its spirit of freedom”. Furthermore, Maria Grazia Chiuri – the creative director behind the collection – also stated that the city inspires people to express their creativity while acknowledging the outsiders who have found their voices in Paris and became artists, writers, and thinkers.

However, Dior’s failure to give credibility to the origins of the jacket has triggered a different voice from the same Romanian community. When they could not recognize themselves in Dior’s discourse, they created their own: the #BihornotDior movement in which there is a voice that demands acknowledgment, but also an anti-globalist voice hiding behind the fight for authenticity and cultural preservation. Within this discourse, the linguistic choices made by La blouse roumaine and Bihor Couture are far from random.

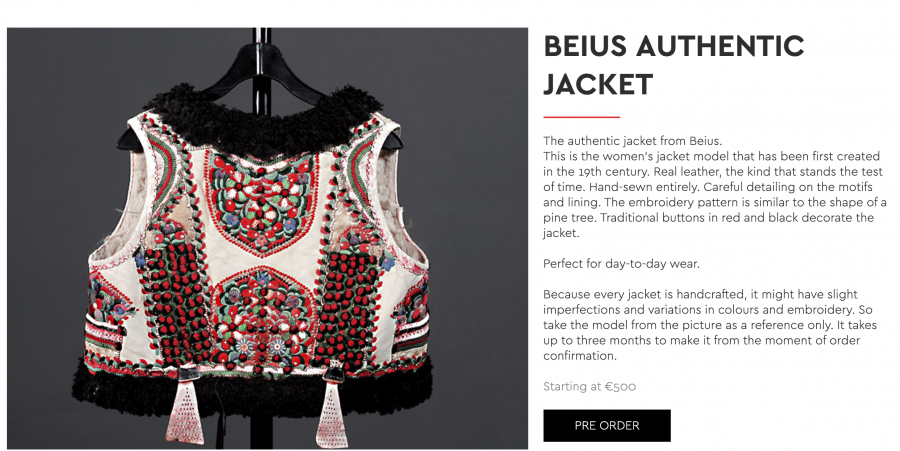

Presentation of the jacket on BIhor Couture website .The description of the Beius Jacket is constructing a discourse about authenticity, heritage and identity.

In their description of the Beius authentic jacket, Bihor Couture mentions the process that went into making the jacket, while putting emphasis on its authentic identity by pointing out the imperfections and variations in the handcrafting. By doing so, it revises and reclaims its history and cultural heritage after Dior copies the model and commodifies the jacket. In the conditions of capitalism, any object that enters the exchange system is inescapably commodified (Rogers, 2006).

Commodification abstracts the value of an object (or form or person) so that it can enter systems of exchange. In this process, the use-value and the specificity of the labor and social relations invested in the commodity are lost; it becomes equivalent to all other commodities (Marx, 1986). Therefore, the model of the Beius authentic jacket suddenly becomes part of a capitalist transactional relationship between a merchant and client so that “the use-value and the specificity of the labor and social relations invested in the commodity are lost” (Crane, 2009).

In return, Bihor Couture reframes the commodity back to its original intentions in the sense that the jacket is handcrafted by the local community and that the social relationship, therefore, is between the authentic producer and the client. Hobsbawm and Ranger (1983) also call the process of re-inserting heritage in contemporary life “part of the ongoing “invention of tradition” in human society” (Hobsbawm & Ranger, 1983).

As mentioned above, there are languages that are more powerful than others, such as English and French. Here, the emphasis is on the emblematic function of language (form), primarily used for aesthetics or identity performances. Emblematic language deals with an indexical function and focuses on symbolizing or emitting globalization, otherness, or Englishness. Language users rely on the iconic values that are attached to certain language forms and within communication processes, the sender can make use of these forms to, for instance, address a wider audience (Spotti, 2020).

On their Instagram page, La blouse roumaine makes use of two different voices: a national one that is aimed at the Romanians with the use of the Romanian language, and an international one targeting a wider online community through the use of English captions. Besides their posts on offering credit to craftsmanship, La blouse roumaine also promotes Romanian culture and cultural fashion in general in the English language. As for Bihor Couture, the website is in English only and thus clearly addresses a global audience - without compromising its local hunch.

It is crucial to mention that Dior never released a statement on the backlash it received from the movement, unlike other instances of cultural appropriation - such as with the Sauvage campaign. But the lack of a voice, in this case, speaks volumes in terms of the power relationship between the exploiter and the exploited.

A Bihor Couture model at Paris Fashion Week

An important change in the power dynamics between local and global takes place when Bihor Couture (meaning artisans who were chosen to represent the image of Bihor Couture) attends Paris Fashion Week, an event that Dior has been part of since the very beginning. As part of their branding campaign, the experience is being captured on camera and shared online for everyone to see. This, in turn, creates a bigger picture, one that encapsulates the “diversification of diversity” (Vertovec, 2007) in fashion-related spaces.

Paris Fashion Week: the “U.N.” of the fashion industry

Paris has been often referred to as the Capital of fashion. Now, if we were to understand fashion brands/houses as “nation-states” then Paris Fashion Week would be the equivalent of a U.N. summit. Like nation-states, fashion houses have their own symbols, history, culture, and cultural artifacts. Because “fashion” doesn’t happen outside of society, it is also political. The history of Fashion Week shows that this is not just an event, it’s a specific configuration in time and space (chronotope) where configurations of power are constantly negotiated, where new cultural configurations are created, and ideologies are being framed within each discourse. As society changed so did the socio-cultural configuration of Fashion Week.

In today’s age, socio-technological platforms have made it possible for what was once considered an exclusive event to be accessed by a wider audience. Additionally, fashion houses want to attract as much consumer attention as possible in this short period of time, therefore streaming their fashion shows live on Twitter and YouTube. But also offline, Paris Fashion Week has become the perfect example of a super diverse space where transnational communities can be found. These are light communities that travel to a certain place for a specific purpose or activity and return to their own community after the said activity is completed (Spotti, 2020). From front-row celebrities, models, and fashion editors to Instagram influencers and the individuals who want their unique styles captured and published in fashion magazines such as Elle and Vogue: the national and ethnic backgrounds of the people present at Paris Fashion Week are extremely diverse.

That is why the presence of Bihor Couture at Paris Fashion Week can be understood as proof when talking about super-diversity both in terms of cultural identities and fashion configurations.

The implications of cultural appropriation in a globalized world

What we tried to argue in this paper is that, with globalization, cultural appropriation becomes a more complex notion, acting on different levels both in terms of practice and in terms of ideology. This, in turn, raises some challenges on how we look at the discourse surrounding it, and what knowledge they share.

Cultural appropriation in the current phase of globalization moves beyond the rhetoric of post-colonial ideology and cultural borrowing. It can also be understood as a counter global movement, that operates both locally and globally, which comes from a need for the preservation of culture and local identity. We observed that cultural appropriation is not power-free, and structures of power are being negotiated and rendered through the use of language and discourse. #BihornotDior is just one example, of many, where big brands have copied, or been inspired by, cultures outside their own without giving credit. Most of the time the reaction of fashion brands is framed as discourse about celebrating diversity, while in turn, we see that with diversity there is also inequality.

References

Cuthbert, D. (1998): Beg, borrow or steal: The politics of cultural appropriation, Postcolonial Studies, 1:2, 257-262

Crane, D., 2009. Fashion And Its Social Agendas. Johanneshov: TPB.

Eze, M.O. (2018). Cultural Appropriation and the Limits of Identity: A Case for Multiple Humanity(ies) 1.

Hobsbawm, E. & Ranger, T. (1983). The Invention of tradition. Cambridge, UK. Cambridgeshire: Cambridge University Press.

Rogers, R. (2006). From Cultural Exchange to Transculturation: A Review and Reconceptualization of Cultural Appropriation. Communication Theory. 16. 474 - 503.

Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implication. Ethnic and racial studies, 30(6), 1024-1054.

Ziff, B & Rao, P.V. (1997). Borrowed Power: Essays on Cultural Appropriation. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press.