How Disney+ is Changing the Streaming Industry through Industrial Convergence

In recent years, there have been countless instances in the entertainment industry of the mixing and matching of practices from the mass-entertainment industry, which is traditionally situated in Southern California (SoCal), with practices from ‘pure-play’ internet companies, which are traditionally situated in Northern California (NorCal). A recent, very successful example of this is the streaming service Disney+, which has integrated elements from both the NorCal and SoCal business cultures into its platform and business decisions.

The success of Disney+’s strategy of industrial convergence could have far-reaching consequences for the future of the streaming industry, which is why this article will analyse how Disney+ integrates elements from the NorCal and SoCal business cultures in its platform and content, and how this could have a lasting effect on the practices of the streaming industry.

Method and Framework

YouTube, Multichannel Networks and the Accelerated Evolution of the New Screen Ecology (Cunningham et al., 2016), as well as, Social Media Entertainment. The New Intersection of Hollywood and Silicon Valley (Cunningham & Craig, 2019) will be used as the primary theoretical framework of the analysis. They describe the NorCal and SoCal business cultures in detail while also providing some practical examples of industrial convergence.

Cunningham and Craig’s research focuses on companies in the field of social media entertainment, which are all companies with a NorCal business culture. They describe the infrastructure of social media entertainment as: “… comprised of diverse and competing platforms featuring online video players with social networking affordances, including YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, and Vimeo.” (Cunningham & Craig, 2019). Their journal paper YouTube, Multichannel Networks and the Accelerated Evolution of the New Screen Ecology (Cunningham et al., 2016) is an in-depth case study on how one of these NorCal internet companies has integrated traditional SoCal business strategies into its own business culture to become more competitive.

However, industrial convergence is not a one-way street; SoCal companies also frequently appropriate NorCal business practices to become more competitive. Cunningham and Craig’s research primarily focuses on NorCal social media entertainment companies, which creates a research gap when it comes to the ways in which traditional SoCal companies adopt NorCal business practices. Taking Disney+, which is part of the SoCal entertainment company The Walt Disney Company, as a case study alleviates this research gap.

NorCal and SoCal businesses learn from each other to become more competitive

Furthermore, what makes the video streaming market particularly interesting to study is that it is a field where both traditionally NorCal companies, such as YouTube (with YouTube Premium) and Apple (with Apple+), and traditionally SoCal companies, such as Disney (with Disney+) and Warner Media (with HBO max), directly compete with each other for consumers’ attention. This makes it easy to compare their business strategies and to analyse whether the observed differences could be the result of their original business culture or the adoption of a practice from the opposing business culture.

Part of the information on Disney+’s business decisions that will be analysed comes from online news reports, primarily from outlets that specialize in news reports on entertainment, technology and popular culture, such as theverge.com and theringer.com. Some of the other information on Disney+’s business decisions was taken from The Walt Disney Company’s online press release and news page.

What is ‘industrial convergence’?

The term ‘industrial convergence’ refers to the way in which companies from the mass-entertainment industry, which are traditionally situated in Southern California, and ‘pure-play’ internet companies, which are traditionally situated in Northern California, integrate elements from each other’s business culture into their own (Cunningham et al., 2016). This is a relatively new development because of the short existence of the NorCal industry, which took shape around 2006 in the time of Google’s acquisition of YouTube, and is a response to the significant change in consumer habits and expectations caused by this new industry (Cunningham & Craig, 2019). Consumers of all kinds now expect to be able to engage with the content they are watching, which relates “to a larger trend across the media industries to integrate digital technology and socially networked communication with traditional screen media practices.” (Holt and Sanson, 2013). This has an influence on the content production of and the usage of technology in the entertainment industry.

The distinction between Northern (NorCal) and Southern (SoCal) California is very evident in their business cultures. The NorCal industry focuses on the creation of the underlying infrastructures needed to enable connected viewing and content hosting but rarely produces content themselves, relying on user-generated content or acquiring content produced in different industries instead (Cunningham, et al., 2006). For the former method of content acquisition, you may think of social media companies like Facebook or YouTube and for the latter method, you may think of companies like Spotify, Apple’s iTunes or Netflix.

The internet infrastructures created by these ‘pure-play’ internet companies are in a permanent beta, meaning they can be rapidly changed when needed, and are dedicated to scale, automation and rapid prototyping. In order to be profitable, a lot of NorCal companies (especially those who rely on user-generated content) collect and possess extensive data on the online behaviour and purchasing habits of their userbase (Cunningham, et al., 2006). This allows these companies to serve their userbase personalized content and advertisements, which not only tempts users to spend more time on the platform but also makes sure that the served ads have a higher success rate (Van Dijck, 2013).

A lot of NorCal companies primarily rely on ad revenue, which is why their practices of content censoring and ad revenue distribution are often influenced by the wary conservatism of the brands and advertisers they work with (Cunningham, et al., 2006). An example of this is what content creators on YouTube call the ‘adpocalypse’: these are multiple waves of content guideline restrictions, resulting in the removal of and suspension of ad revenue on multiple channels after controversy on the platform, which made advertisers pull their advertisements from the site. The Diggit article ‘YouTube's demonetization situation and the adpocalypse’ goes more in-depth on the first wave of the adpocalypse.

The SoCal business industry, on the other hand, focuses on professional content production of mass media entertainment and the distribution of this premium entertainment. Although it is more difficult for this industry to collect extensive data on consumers of its products, the industry does have the advantage of having a long history of traditional marketing research (Cunningham, et al., 2006).

NorCal companies can both be indirect competitors or allies for SoCal companies and vice versa. After all, although both industries compete for the consumer’s limited time and attention, their content often has differing functions. Furthermore, the engagement around and sharing of SoCal produced entertainment brings traffic to the platforms created by the NorCal industry, which in turn “creates buzz that is increasingly valued by the media industry.” (Jenkins, 2006). This media convergence, by which we mean “the flow of content across multiple media platforms, the cooperation between multiple media industries, and the migratory behaviour of media audiences who will go almost anywhere in search of the kind of entertainment experiences they want” (Jenkins, 2006), is beneficial for both industries.

However, as mentioned before, this dynamic is changed in the field of streaming. Here, both NorCal companies and SoCal companies are directly competing with each other and are therefore creating platforms and content with a similar function. In order to stay competitive and see what works best in grabbing and holding the attention of the consumer, these NorCal and SoCal companies must learn from each other’s industries. Like other streaming services, to be a successful competitor, Disney+ has had to adapt.

Disney+’s integration of NorCal & SoCal business strategies

Disney+‘s parent company, The Walt Disney Company, has traditionally been a SoCal company since its inception in 1923. The company started with the production of animated short films for the movie theatre and eventually moved on to feature-length movies. Its market share of the mass media entertainment market has increased tremendously since its headquarters moved to Burbank in Southern California in 1939. Over the decades, the company has diversified its revenue stream by entering into and profiting of off new markets, such as the theme park industry with parks like Disney World in Orlando, and the cable industry which they entered with the debut of the Disney Channel in the 1980s (Sanders, 2019). Next to a diversification of revenue, there has also been a diversification of content; in the 2010s The Walt Disney Company diversified their content library and production with the acquisition of Pixar and Marvel (Sanders, 2019).

However, Disney’s acquisition of Fox in March of 2019 was made for a different reason than merely the diversification of its content library and production, and that reason is Disney+. In an interview with CNBC, Bob Iger (at the time the CEO of The Walt Disney Company) explained the acquisition: "The opportunity to buy Fox first came up later that year. In fact, just a few months after the board approved us buying the majority share of BAMTech — which was done for one reason, to go into the direct-to-consumer business — Rupert and I sat down and talked about a transaction. We would not have done that transaction had we not decided to go in this direction.” (Franck, 2019). A few months prior Iger also stated that Disney’s direct-to-consumer business (which includes Disney+) is the company’s top priority (Roberts, 2019).

This increased the pressure on Disney+ to succeed and the integration of both NorCal and SoCal business culture elements into the content and the technological infrastructure that supports the content seems to be one of the ways in which Disney+ is hoping to accomplish this. This is why the next section will discuss Disney’s business decisions on the content and platform architecture of Disney+.

Content decisions: Sticking to your SoCal roots

Unlike Netflix, which got its start in the field of online streaming with the idea of merely being a content hosting platform before it started producing originals, Disney+ was initially created with the intention of both being a content hosting platform and a place for the release of original premium content. We can clearly see this intention in the previously explained decision to acquire Fox (Disney seals $71bn deal, 2019). Not only has the acquisition given The Walt Disney Company access to Fox’s huge library of content, but the Fox division will now also be working on reimaginings of classic Fox movies for Disney+ such as “Home Alone”, “Night at the Museum” and “Diary of a Wimpy Kid” (Donnelly & Lang, 2019).

Moreover, another difference in content acquisitions between Netflix and Disney+ is that almost all of Disney+ originals are produced in-house by subdivisions which it owns, whereas a lot of Netflix originals are outsourced to other studios like DreamWorks. This shows the difference between Disney’s speciality as a SoCal media producer and Netflix’s speciality as a NorCal content hosting platform. This approach is advantageous for Disney because the company has a larger control over the production and distribution of the content. Unlike Netflix, this also means that Disney does not need to pay fees for the IPs that it hosts on its platform. These latter two advantages are also reflected in the, previously mentioned, CNBC interview with Iger in the video below.

Disney+ and Netflix also show differences in their preferred schedules for content releases. Netflix is infamous for its ‘binge model', meaning the platform usually releases the new seasons of its shows all at once. Disney+, however, sticks closely to its SoCal roots with its new content releases closely mirroring traditional television broadcasting schedules. For example, the episodes of season 2 of ‘The Mandalorian’ premiered weekly on Disney+ around 12 am PST (Next episode Mandalorian, 2020).

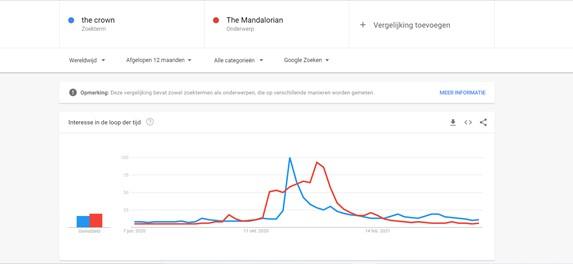

This business strategy works in Disney+’s favour because it spreads out consumer engagement over multiple weeks instead of only sparking a heavy, short debate online, which in turn builds a bigger audience for the show. This is reflected in figure 1, which shows the peak popularity for the search term “The Mandalorian” (a show by Disney+) in comparison to the peak popularity of the search term “The Crown” (a show by Netflix). The popularity of the term “The Mandalorian” slowly increases over the weeks until it is almost as popular as “The Crown”, which shows a steep peak the day the new season dropped.

Figure 1) A comparison between the search popularity of "The Crown" and "The Mandalorian"

Viewers also appreciate the social aspect that watching the show weekly brings. Miles Surrey, a movie critic for the entertainment news site theringer.com, writes: “As someone who enjoys the discussion around shows almost as much as the experience of viewing them, 2019 has provided compelling evidence that weekly viewing appointments have the sort of hype-generating power that even the most popular shows of the binge model can’t replicate—particularly in the long run.” (Herman & Surrey, 2019). Although the article notes some cases in which binge-watching may be favourable, weekly release schedules generally seem to satisfy consumer expectations regarding engagement better.

Lastly, to mitigate the loss of theatre revenue and to cater to those not willing to risk going to the theatre in Corona times, Disney+ introduced the premiere access option, which allows Disney+ users to gain access to Disney movies that have recently been released for a fee of $29.99 (US dollars) (Cohen, 2021). This business decision combines the exclusivity of an early access release for the consumer with the old SoCal distribution practice of renting movies.

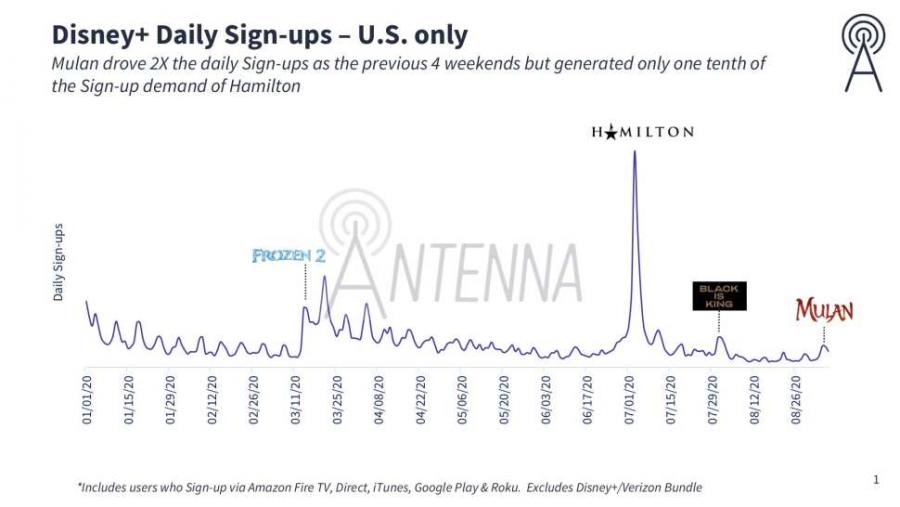

However, the success of “Mulan”, which is the first (and was originally going to be the only) movie with premiere access, is dubious and hotly debated (Labonte, 2020). Although “Mulan” doubled the daily sign-ups to Disney+ as compared to the 4 weeks before, as shown in figure 2, and, based on estimations, earned $33.5 million dollars in its opening weekend on Disney+ (of which the company gets to keep 100 per cent), its daily sign-ups are lacklustre in comparison to the bump brought by properties such as “Hamilton” (Katz, 2020) and its box office number, which is currently around 70 million on a budget of 200 million, disappointed.

Figure 2) "Mulan" opening weekend new Disney+ subscribers

Disney+ has released more movies with their premiere access feature since “Mulan” because of the continued problem of Covid-19. But, The Walt Disney Company’s current CEO, Bob Chapek, has stated that the company is not committed to keeping the feature moving forward in 2022, due to its failure (Bowman, 2021). This shows that Disney+, like platforms created by traditionally NorCal companies, can be changed rapidly when needed and adapt to any failures or successes.

Platform decisions: Following the new screen ecology

Speaking of the platform infrastructure, the company that Disney acquired to build and run Disney+ -formerly known as BAMtech Media- has a typical NorCal business culture even though its headquarters are situated in Manhattan, New York. This company launched multiple other streaming services before its development of Disney+ like WWE Network, HBO NOW and Hulu. “BamTech also has impressive advertising technology (inserting ads in video based on viewer location) and a strong reputation for attracting and keeping viewers, not to mention billing them.” (Barnes & Koblin, 2017).

Another feature that BAMTECH developed for Disney+ is the ability to simulcast a show or movie, which encourages connected viewing and allows friends to watch the same movie or show while in different places. This is especially useful in times of Corona. The app or site can also be used on almost any device. Users can watch their favourite Disney+ shows and movies on their laptop, computer, Smart TV, tablet and phone.

Undoubtedly using BAMtech’s experience in advertising technology, Disney+ uses (similarly to NorCal companies like Netflix or YouTube) algorithmic prediction to serve users of the platform personalized content suggestions. The data collected on what users enjoy can then be used by Disney to increase the watch time of its users, further the market penetration of the platform and develop successful content production strategies. This is also why there can be multiple profiles on a single account. It allows the platform to collect data on individual users and select their recommended content accordingly. Iger, in his previously mentioned interview with CNBC, also reported that a large goal of Disney+ is to get to know the consumer better and provide them with a more personalized experience.

Lastly, the way the layout of Disney+ is structured is reminiscent of traditional SoCal cable package channel divisions. The top row of the platform, under the banner advertisements, as shown in figure 3 is dedicated to various content categories based on the (acquired) subdivisions of The Walt Disney Company: Disney, Pixar, Marvel, Star Wars, National Geographic and Star (which hosts Fox’s adult content and other adult content). Like a traditional cable, a paying user might not be interested in every type of content available to them and this layout helps users find the content they enjoy.

Figure 3) The lay-out of Disney+'s homescreen

How Disney+’s success might change the streaming industry

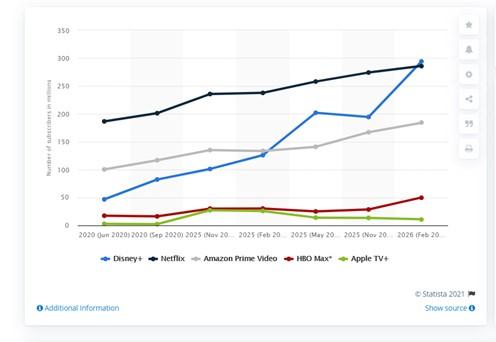

So far, Disney+ has been massively successful. On March 9th of this year, the global number of paid Disney+ subscribers surpassed 100 million and that number of global subscribers is only expected to grow in the coming years. It is even estimated by Statista, in figure 4, that Disney+ could surpass Amazon Prime in 2025 and Netflix in 2026, which is currently the biggest streaming service with 201 million paid subscribers. Of course, Disney’s content and brand identity as a well-known and beloved entertainment company help Disney+ in its success, but its business strategies, which take influence from its original SoCal business culture and the NorCal business culture, have a significant influence on its success as well.

Figure 4) Streaming video on demand subscriber count worldwide 2020-2026

Surprisingly, however, although Disney+ adopts some elements of the NorCal business culture, such as its content recommendation algorithm, the company closely sticks to its SoCal roots, especially when it comes to decisions on the platform’s content. This has generally been working in its favour. I personally suspect that The Walt Disney Company has taken this approach on the basis of its extensive database of traditional marketing and audience research, which has only grown bigger because of its acquisition of Fox (Disney seals $71bn deal, 2019). This begs the question: will we be seeing an increase of SoCal business practices in the field of streaming which started as a NorCal business dominated field? Based on Disney+’s success, this is very likely.

A complete overhaul of the NorCal business culture practices by SoCal business practices is unlikely, nor should we -in retrospect- ever have expected the field of streaming to remain a NorCal dominated space. Instead, I predict that we will see a solid integration of practices from both business cultures into the business strategies of both traditionally NorCal and SoCal companies in the streaming field. In fact, this change is already visible; Netflix has started to implement weekly releases of its shows “Patriot Act”, “Rhythm + Flow”, and “The Great British Baking Show”.

This conclusion shows that SoCal companies can conquer the challenge posed by the new screen ecology described by Cunningham, Craig & Silver: “…firms that have long dominated the mass media may now face the most serious challenge in their history. Hollywood tried and, with the partial exception of Hulu, failed to establish viable online distribution businesses since the first attempts dating from 1997.” (Cunningham, et al., 2016). Disney+ has shown that SoCal companies do not only conquer this challenge; they can thrive and influence the business practices of the streaming field in the process.

References

Barnes, B. & Koblin, J. (2017, October 8). Disney’s Biggest Bet on Streaming Relies on Little-Known Tech Company. The New York Times.

Ben, B. (2021, May 13). Disney+ May Not Continue Premier Access in 2022. The Streamable.

Cohen, S. (2021, June 1). Disney Plus Premier Access lets subscribers buy new movies like 'Cruella' while they're still playing in theatres. Business Insider.

Cunningham, S., Craig, D. & Silver, J. (2016). YouTube, Multichannel Networks and the Accelerated Evolution of the New Screen Ecology. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media, 22(4), 376-391. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856516641620

Cunningham, S. & Craig, D. (2019). Social media entertainment. The New Intersection of Hollywood and Silicon Valley. New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/9781479838554

Disney seals $71bn deal for 21st Century Fox as it prepares to take on Netflix. (2019, March 20). The Guardian.

Donnelly, M. & Lang, B. (2019, August 13). Fox Feels the Pressure From Disney as Film Flops Mount. Variety.

Frank, T. (2019, April 12). Iger Says Disney Bought Fox Because of Value it Adds to Streaming Service: ‘The Light Bulb Went Off’. CNBC.

Herman, A. & Surrey, M. (2019, November 26). To Binge or Not to Binge—That Is the Question. The Ringer.

Holt, J. & Sanson, K. (2013) Connected Viewing: Selling, Streaming, & Sharing Media in the Digital Era. Routledge.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York University Press. https://doi-org.tilburguniversity.idm.oclc.org/10.18574/9780814743683

Katz, B. (2020, September 16). Was ‘Mulan’ an “Unmitigated Disaster” or a Success? It’s Complicated. Observer.

Labonte, R. (2020, November 12). Disney CEO Hints At More Mulan-Style Disney+ Premier Access Releases. Screen Rant.

Roberts, D. (2019, February 6). Disney Says Streaming Is Now Its 'Number One Priority'. Yahoo!Finance.

Sanders, A. (2019, November 15). A Brief History of the Walt Disney Company. The Ups and Downs of the Beloved Entertainment Giant. Lifewire.

Van Dijck, J. (2013). The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford University Press.

When is the next episode of The Mandalorian season 2? Keeping track of Disney Plus’ often weird release schedule. (2020, November 6). Polygon.