Jacinda Ardern: New Zealand's most eminent political influencer

Jacinda Ardern is one of the most popular politicians worldwide. If not known for her jumpstart career or being the youngest-ever female Prime Minister of New Zealand, then she is known for being praised by international media for guiding her country through challenging times and multiple crises during her first term in office. Despite her lack of experience in politicals, Ardern shephered New Zealanders through the Christchurch mosque shootings, the Whakaari/White Island eruption, and now the Covid-19 pandemic. This paper explores on how Jacinda Ardern used social media to boost her popularity and remain a relevant asset to the parliament and the people of New Zealand in the lead-up to her reelection.

‘Jacindamania,’ or the rise of Ardern’s popularity

In 2017, the young politician became leader of the Labour party, after Andrew Little resigned due to a low polling outcome. Only 8 weeks away from the general election, Ardern was thrown in the deep end, but surprisingly started swimming immediately. The media soon hit the party leader with many controversial questions. When a reporter asked if she was planning on having children, she agreed to answer the question since she now had a public role, but added the following: “For other women, it is totally unacceptable in 2017 to say that women should have to answer that question in the workplace” (Shuttleworth, 2017). “Jacindamania” instantly erupted.

From that point on, Labour did exceptionally well in the polls, and entered parliament after the 2017 general election, making Jacinda Ardern the youngest-ever female Prime Minister of New Zealand. It quickly became clear that Ardern, then more of a political curiosity, was not a typical politician. With a background in communication, the PM is internationally seen as a new kind of unconventional 21st-century leader. When Ardern was invited to meet the Queen of England, she wore the korowai, a traditional Māori cloak, while pregnant, to Buckingham Palace (Graham-McLay, 2018).

Her leadership is about empathy, about making New Zealanders feel heard but also supported.

The Prime Minister’s first term turned out to be a turbulent ride. In 2018 her daughter Neve was born, which made Ardern only the second Prime Minister worldwide to give birth while in office. While being a mother and a PM at the same time sparked an international conversation about the role of working women, Jacinda Ardern had big goals for her leadership (Graham-McLay, 2018). Housing, child poverty, and climate change were on the top of the government’s list. In 2019 a white supremacist murdered 51 people at two Christchurch mosques and Whakaari/White Island erupted, killing 21 and injuring more (Shaw, 2020). As if that was not enough, the Covid-19 pandemic hit in early 2020. Dealing with these three crises not only pushed other objectives to the background but also shaped Jacinda Ardern’s career as a global leader – it was a make-or-break moment.

Jacinda Ardern: a perfect brand

Jacinda Ardern is forging a path of her own. International media have highlighted her progressive values, youth, charisma, and status as a mother, bringing more attention to the small country than ever before (Graham-McLay, 2018). But what exactly is so different about her?

Ardern is all about kindness. On the Labour party’s website, Ardern is quoted saying: “If I could distil it down into one concept that we are pursuing in New Zealand it is simple and it is this: Kindness” (Labour, n.d.). Her leadership is about empathy, about making New Zealanders feel heard but also supported. Everyone is part of 'the team of five million', as she refers to her country's population.

With the ‘team of five million’, Ardern takes on somewhat of a motherly role for the nation, with her own feminist touch. With her ethics of care, trust, responsibility, and duty, she focuses on not just one subgroup, for instance differentiated by gender or race, but the entire population as one team (Pullen & Vachhani, 2020). Scholars highlight that Ardern’s openness can be seen through her ethics displayed in her embodied relational practices, such as wearing the traditional Maori cloak to respect and honour the traditional owners of the land and wearing a head scarf after the Christchurch shootings to meet with members of the Muslim community. Pullen and Vachhani (2020) add that “whilst symbolic, these embodied gestures carry agency which shifts the focus from the individual leader and the responsibility attributed to them, to what she can inspire collectively, thus carrying ethical and political significance”. Thus ascribed features of femininity, which were previously and still are rejected in politics, have proven to be the focal point of Ardern’s political success.

It seems like Ardern represents a transformation or a shift of tone in politics rather than a fixed ideology. Her leadership shows that compassion can radiate respect, but also power. It creates a bond of trust between the political persona and the people, rather than forming a hierarchical power structure. As Shaw (2020) puts it, she “resonates with people for whom politics is fundamentally relational rather than ideological”. In times of stress and uncertainty, Ardern makes people feel that they are 'allowed' to vote outside their usual voting spectrum. Individuals feel comfortable voting for Ardern, although they do not agree with her political party, which, to a certain extent, disconnects her public persona from her political party. This particular voter behaviour was seen in the 2020 general election, which revealed that people from all political stances voted for Ardern and the Labour party, creating the biggest voter shift in over a century (Vowles, 2020).

It seems like Ardern represents more of a transformation, a shift of tone in politics rather than a fixed ideology.

On the party’s website, Labour's primary issues and goals are listed: housing, child poverty, climate change, Covid-19 and economic recovery. One of the traditional ways in which Ardern’s political persona is understood by the public is through the issues she identifies with (Lempert & Silverstein, 2012). What makes a difference in Ardern’s leadership is her relentless positivity. This positivity can be seen in everything she does, from press conferences to meetings with other politicians or civilians, to the Labour party’s website and especially on her social media accounts.

The Atlantic explains that “her messages are clear, consistent, and somehow simultaneously sobering and soothing” (Friedman, 2020). But it is not only about the messages Ardern communicates as a leader but also the message of her political persona, her brand or “the politician’s publicly imaginable ‘character’ presented to an electorate, with a biography and a moral profile crafted out of issues rendered of interest in the public sphere” (Lempert & Silverstein, 2012, p.1). In other words, a politician’s message is the sum of everything he or she does, good and bad.

Jacinda Ardern’s message is carefully crafted from different angles. According to Lempert and Silverstein (2012) message is constructed through different talking points, issues, and platforms, such as the Labour party’s website, social media and also outer appearance. An example of Ardern’s message can be seen in figure 1, where she is wearing a traditional Māori cloak to Buckingham Palace, which represents respect for but also from the Māori, indigenous to New Zealand and their culture. As always, Jacinda can be seen smiling and boosting positivity.

Figure 1: Ardern wearing a Maori cloak to meet the Queen

Jacinda Ardern’s moves align, summing up her message and ideology and therefore her brand. As Lempert and Silverstein explain, “[m]essage is not only being shaped as brand, but, for at least some in political life, Message is brand” (Lempert & Silverstein, 2012, p.51). The last missing piece to fully understand her message is Ardern’s use of the new hybrid media system on a day-to-day basis, as her message is spread both online and offline. The blend between traditional media and new media, such as Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, gives politicians a youthful nonchalance and celebrity feeling while providing a platform for discourse.

Authenticity and the hybrid media system

A typical Facebook live session with Ardern starts with her saying “kia ora,” a greeting wishing good health in the indigenous Māori language. She then goes on to talk about whatever issue she came to discuss. This happens either at her office, right before or after important events, or in casual wear at her home, showing a more private side of the Prime Minister. Just before the last general election, Ardern’s Facebook following alone was four times greater than those of the seven other main party leaders (Kapitan, 2020). She uses Facebook as a medium to support her message and political persona online, creating a place for conversation and discourse.

Jacinda quickly became known for checking in with her audience on a regular basis, especially during the outbreak of Covid-19. According to a new study, her approach to update the public from her private home in a time of crisis showed honesty and compassion and created a ‘team of five million’ against the virus (Glasgow Caledonian University, 2020). The study found that the “positive and consistent messaging used on social media helped create a sense of unity across the country” and opened up a “weekly dialogue with citizens, highlighting process and challenges in combatting the virus” (Glasgow Caledonian University, 2020). This shows that Ardern’s commitment to including and engaging her followers and fellow New Zealanders helped form a bond between the two.

Jacinda uses her online platform to update her followers about current events, usually right after they happen, in order to correct her standpoint and message.

Ardern not only makes use of social media but also uses various forms of media in the hybrid media system. Chadwick (2017) stresses the interconnection and interdependence of all current media, such as radio, newspaper, television, social media, and blogs. Chadwick explains that in this system, “[a]ctors create, tap, or steer information flows in ways that suit their goals and in ways that modify, enable, or disable the agency of others, across and between a range of older and newer media settings” (Chadwick, 2017). Ardern here makes use of dual screening in order to control her message online. In politics, dual screening is typically used to discuss a political debate on TV on an online platform, such as Twitter (Chadwick, Dennis & Smith, 2016). Jacinda uses her online platform to update her followers about current events, usually right after they happen, in order to correct her standpoint and message.

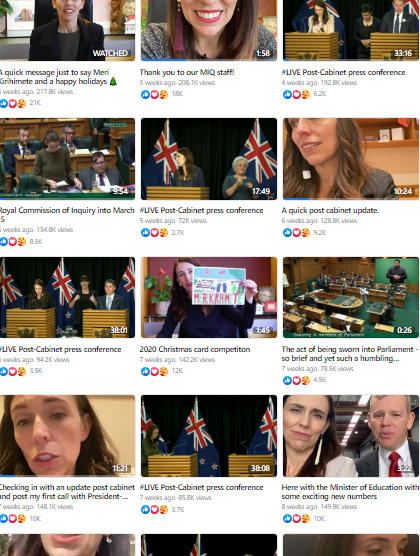

Figure 2: Jacinda Ardern on Facebook

As seen in Figure 2, Jacinda Ardern makes frequent use of the Facebook live feature. One detail immediately stands out – her more informal videos shot with the front-facing camera attract double the clicks (if not more) versus live streams from other settings, such as post-cabinet press conferences. The numbers differ from 80.000 to 217.000 views between the videos. In her informal videos she comes across as disarming, comfortable, and even relatable. She gives a deeper insight into her work life but also her private life, making her come across as extremely authentic.

Figure 3: Jacinda Ardern on Instagram

Facebook is not Ardern’s only point of online influence. She has become more and more active on Instagram, where she frequently goes live and posts a multitude of photos throughout the week. As visible in figure 3, the main topics on her Instagram feed are people from different walks of life (top right), documentating her life as a working professional (bottom left), and everyday things, such as nappy cream on her clothes (centre). Additionally, she showcases communication with kids and children in school, general information such as Covid-19 measures (left and bottom centre), and lastly criticism and frustrations.

She is spreading kindness and positivity in an imperfect and authentic way.

Ardern knows that the key metric on Instagram and Facebook is engagement – the currency of the influencer world. More clicks, likes, comments, and shares mean more visibility and conversation. Therefore, Ardern is simply staying right ‘on message’. She is spreading kindness and positivity in an imperfect and authentic way. Authenticity here gives Ardern the chance to make politics believable and create trust. She believes that power can be accompanied by empathy, compassion and kindness.

Jacinda Ardern as a political influencer

“Jacindamania” is proof of Ardern's online popularity. The hype around the prime minister has continued well past her initial election in 2017. She is making use of her positivity by sharing her candid thoughts and emotions online with the people of New Zealand, but also with the rest of the world. With her unconventional leadership style and carefully constructed message, she succeeds in creating an offline but also online community of the people of New Zealand – a ‘team of five million’.

Thus, with her online popularity, the politician also creates a space for discourse and exchange. She offers ‘her people’ a platform to exchange ideas, questions and concerns, and therefore builds a bond of trust between the population and the government. Due to her authenticity, her followers are taking others into consideration, spreading empathy, positivity and kindness: Ardern’s goal from the start. The New Zealand prime minister is rare in the sense that she is a highly visible social media celebrity as well as a political leader. This shows that she is indeed competent in what she does, and maybe even more experienced than some other global leaders.

References

Chadwick, A. (2017). The hybrid media system. Politics and power. Oxford University Press.

Chadwick, A., Dennis, J., & Smith, A. P. (2016). Politics in the Age of Hybrid Media: Power, Systems, and Media Logic. In A. Bruns, G. Enli, A. O. Larsson, & C. Christensen (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics. Routledge.

Friedman, U. (2020). New Zealand’s Prime Minister May Be the Most Effective Leader on the Planet. The Atlantic.

Glasgow Caledonian University. (2020). Study hails Jacinda Ardern's use of Facebook Live during pandemic.

Graham-McLay, C. (2018). Jacinda Ardern’s Progressive Politics Made Her a Global Sensation. But Do They Work at Home? New York Times.

Kapitan, S. (2020). The Facebook prime minister: How Jacinda Ardern became New Zealand's most successful political influencer.

Lempert, M., & Silverstein, M. (2012). Creatures of politics: Media, message, and the American presidency. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

NZ Labour Party. (n.d.). Rt Hon Jacinda Ardern.

Pullen, A., Vachhani, S.J. (2020). Feminist Ethics and Women Leaders: From Difference to Intercorporeality. Journal of Business Ethics.

Shaw, R. (2020). NZ election 2020: Jacinda Ardern promised transformation - instead, the times transformed her.

Shuttleworth, K. (2017). Jacindamania: Rocketing rise of New Zealand Labour's fresh political hope. The Guardian.

Vowles, J. (2020). The 2020 NZ election saw record vote volatility - what does that mean for the next Labour government?