The Migrant Identity: The Role of Art and Media in Identity Formation

Migration is one of the most important societal issues of our time. “It is also perhaps one of the only phenomena that radically differentiates our era from the nineteenth century" (Groys, 2017). Not only do migratory practices influence our political climate, they also have a direct impact on how we shape our perception of migrants with a different cultural background than our own. At the same time, digitalization has led to a globalized world that is shaped by images we encounter online and in the media. The aesthetic properties of images can play a role in how we perceive ourselves against the other. This implies that identity formation is visually embedded within the images we come across every day. One of the strongest visual practices is that of art. Within artistic migrant practices, some artists use their work as a form of political construction and claim that we need artistic expressions and interventions to establish a social movement to recreate our common world.

The media has a way of showing the migrant identity in the context of mainly problematic and political issues, could artworks provide a better representation for those that have experienced migration? The visual images imply that being in constant crisis could enhance inequality between migrants and society. Migrant artists can shape their identity through the use of artworks, to contradict the migrant image shaped in the media.

To provide an in-depth analysis of this main argument, three different cases of migratory art practices will be analyzed according to existing migratory frameworks. The main argument we build in this paper is based on the claim that art can provide a counter-discursive narrative for individuals that are confronted with political issues, being presented as the ‘other’, and find themselves in-between various socio-cultural structures in society. Furthermore, art can not only give a voice to individuals whose experiences are not always recognized in the mainstream media but we willframe those experiences in a more understandable and positive scenario.

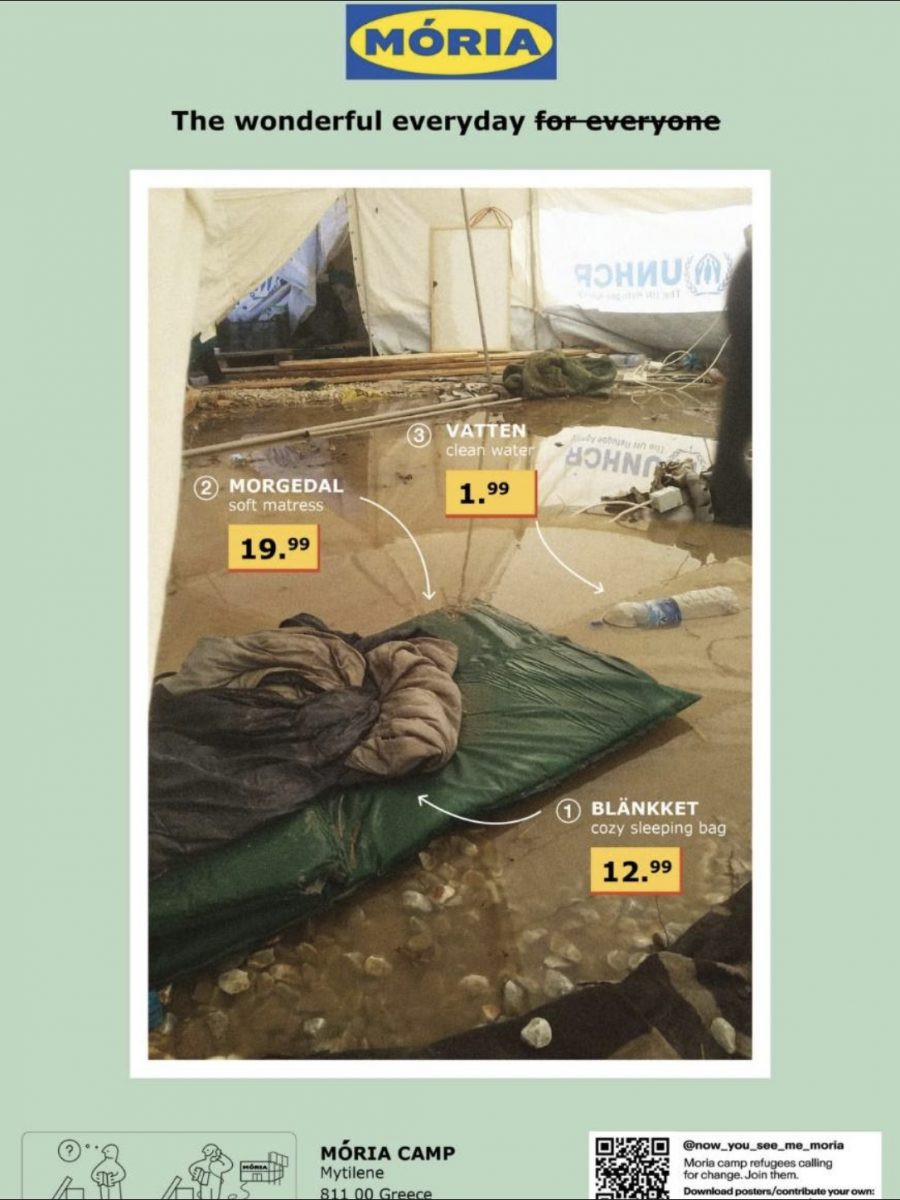

Firstly, we will discuss the photography project, Now You See Me Moria (2020). This activistic project was launched on Instagram to raise awareness for the poor living conditions during the global COVID-19 pandemic in the Moria refugee camp in Greece. Journalists are banned from taking pictures in the camp, mainstream media and the art world have directed their attention to this project, creating more visibility in the public sphere. How is the migrant identity portrayed in this project, and how does the flow of the images impact its activistic nature?

Secondly, we will provide an in-depth analysis of how the migrant identity is visible in art through the work of Indian artist Nalani Malani. Malani, a migrant herself, uses different media to present an authentic migrant experience that is then transferred from a semi-public space such as a museum into the public sphere. Here, we will focus on her exhibition Transgressions, which was open to the public in 2017 at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. We will focus on what elements of migrant aesthetics are visible in her work and how she intertwines her concerns about the influence of globalization on the local Indian culture within this work.

Lastly, we will discuss the Iraqi artist Hayv Kahraman. As a refugee she fled Iraq and settled in Sweden, where she felt like an outsider. In her work, she focuses on her own female migrant body. She conceptualizes new forms of migrant identitiesby merging cultures in different artistic approaches and using her own migrant narrative. The analysis focuses on the presentation of the (female) migrant identity as presented in her artworks for which we will focus on three of her paintings. This will provide a framework to explore how Kahraman uses her body as a voice against the hegemonic and patriarchal powers.

These three cases will show that migratory aesthetics can be visualized in artistic practices in various ways. They can be a tool for activism, they can use the migrant experience as a visualization of the local/global dichotomy, or they can question the status of the migrant as an outsider. This research will focus on the borders between the migrant as an individual subjected to bias and othering, and migratory art as a powerful tool to share the migrant experience or focus on important socio-political issues in society.

Art and Activism

Artistic practices can be a useful form to engage with political and societal issues. Philosopher Chantal Mouffe explains how politics and art are never two opposites and how art does not need to have politically-charged content to comment on political issues. “There is an aesthetic dimension in the political and there is a political dimension in art” (Mouffe, 2007). The ‘agonistic approach’ that she describes is based on determining what the dominant consensus in society tries to undermine. Consequently, this approach, “is constituted by a manifold of artistic practices aiming at giving a voice to all those who are silenced within the framework of the existing hegemony” (Mouffe, 2007). Artistic practices could in this way function as a counter-cultural voice against the hegemonic system within politics, making it an interesting approach to discuss important societal issues.

Artistic practices could function as a counter-cultural voice against the hegemonic system within politics, making it an interesting approach to discuss important societal issues.

The role of art in society is further explained by Boris Groys. In his book Art Power (2013), he discusses the frameworks and conditions in which the structural powers of art become visible. On one hand, art functions as a commodity, on the other it can be a “tool of political propaganda” (Groys, 2013, p. 5). We should be aware that when art presents itself to the public, it has implications on society, but only when it can distance itself from the art market. This does not mean that politically engaged art can never establish itself within the art market, rather it means that “production, evaluation, and distribution do not follow the logic of the market” (Groys, 2013, p. 6-7). The work of art is usually not perceived as a commodity by the majority of the audience. When art is brought into the public by the means of exhibition, most will position themselves against the work of art as a work of art. In this way, the public can engage with the position of the artist as “they react to the tools by means of which individual artists position themselves in public space as objects of observation, for today everyone is obliged, one way or the other, to present him- or herself in public space” (Groys, 2013, p. 179). This need to present yourself as an artist in the public space is where the identity of the artist becomes embedded in the work of art.

Art can provide us with different views from all aspects of society and cultural diversity becomes an important aspect here. The individual can present itself in art and “this provides for a frame in which the individual looks at the world, and, therefore culture” (Groys, 2013, p. 150). The enlarged affection of the visual on which our information intake relies has implications on how we perceive political information. The use of art in politics is usually considered irrelevant and ignored. (Groys, 2013, p. 179) However, we cannot forget, the ability of art to reflect on society is a reliable way to position ourselves against the individual as ‘alien’ in contemporary culture than political discourses.

Identity Shaping in Art

Identity is shaped through the image that others provide for us. This becomes clear when Groys discusses the following, “Because I as an individual cannot take in the whole, I must necessarily overlook something that can only be evident to the gaze of others. These others, however, are by no means separated from me culturally: I can imagine them in my position, just as I can imagine myself in theirs” (Groys, 2013, p. 182). This shows the power of imagination that art can provide for us. In a world where bodies are separated, art closes the gap between ourselves and others.

Artistic encounters can connect us to others, but they can also detect the differences between cultural identities. This creates tension between inclusion and understanding, and antagonism, racism, and enlarged differences between people in contemporary art practices. In her book Migration into Art (2017), Anne Ring Petersen states that the work of art needs recognition beyond the identity formation of the artist, without focusing on aesthetics alone. Rather, the work needs to be recognized for its “sensory, affective, cognitive, political and historical strata” (Petersen, 2017, p. 81). Furthermore, “we need to find ways to deconstruct the misconception that the artist’s ‘authentic’ ethnic roots and cultural identity are always the prime sources of the work’s meaning” (Petersen, 2017, p. 81). Since the work is embedded in multiple areas, and identity is already a complex term, we are inclined to focus on all existing elements in order to analyze artistic practices.

Migratory Aesthetics

Migratory aesthetics are not bound to the conceptualization of the migrant experience in the artwork, rather, it reflects “an art that is fundamentally shaped by the effects of migration” (Petersen, 2017, p. 58). Migratory art differs from media and documentary perspectives about migrants since its focus is more on a culture that has been transformed by migratory practices rather than presenting migrants as a minority culture. We should be aware that aestheticizing the migrant experience can turn it into a general image of the migrant identity and “an almost universalised multicultural or cosmopolitan ideal” (Petersen, 2017, p. 59). But, this works twofold by making sure that denying the aesthetic component in migratory art practices leads to denial of the “participation in the cultural transformation of society” (Petersen, 2017, p. 59). In this way, aesthetics and identity are both equally important in artistic migratory practices.

Petersen further describes how identity within migratory art practices is usually connected to the cultural aspect of identity which focuses on the collective cultural and ethnic roots of the artist. She uses this term to deconstruct the complexity of identity and to show that we cannot simply make a clear distinction “between a person’s psychic, social and cultural identity” (Petersen, 2017, p. 66). Furthermore, she points to the infrastructure of art institutes and how globalization has led to “cross-fertilisation at all levels of art production and circulation” (Petersen, 2017, p. 68). Global art is a much-discussed term within the art system and connects directly to migratory art practices. We are inclined to categorize artists according to their place of birth or place of residence which leads to “more sophisticated forms of exclusion masquerading as inclusion” (Petersen, 2017, p. 68), making it difficult for non-Western artists to have the same recognition as Western artists.

Global Art

Art can be seen as an open system in our global society. Globalization is connected to the rise of the internet, which has led to gained visibility for art across the globe. Still, art constitutes a world separated from society which is based on a “community of artists, curators, collectors, critics, scholars, and associated institutions and professionals” (Petersen, 2017, p. 2). We could question whether the artworld truly is disconnected from society, as we discussed earlier, art is interwoven in the societal, political, and cultural spheres and an important factor in criticizing them. The migrant identity has become a more common image because of the various ways it is represented in art. The adaptability of the work of art is manifested in the mobility of images. (Petersen, 2017, p. 2) This shows the connection between the image of migrants within but also outside the art field.

The global aspect of images is explained by Thomas Nail in his Handbook of Art and Global Migration (2019). He argues that:

“Today, it is possible for anyone to communicate by voice or text with anyone else; to listen to almost every sound ever recorded; to view almost any image ever made, and to read almost any text ever written from a single device and from almost any location on Earth.” (Nail, 2019, p. 60)

As Nail mentions, the image will never be the same, including the migrant image. The digital image, much like that of the migrant, is mobile. Not just by virtue of its form but by the mobility of its content, recipient, and author (consumer and producer). “Some of the most shared and viewed images of the past few years have been digital images of migrants, refugees, and the conditions of their travels, and even their death” (Nail, 2019, p. 61). Widespread access to cell phones with digital cameras has benefited migrants and refugees in that they can make themselves more visible. Nail argues that it allows them to generate more images “of their own movement and experience than ever before” (Nail, 2019, p. 61). This contributes to the nomadic flow of images and could potentially provide for a more authentic image in regards to the migrant identity.

The digital image, much like that of the migrant, is mobile. Not just by virtue of its form but by the mobility of its content, recipient, and author (consumer and producer).

It is important to note that exposure to the material artwork usually happens in a local context. Museums and other art institutes mostly reach an audience that is based close to the physical exhibition space, and therefore goes against the notion of global art. This could again imply that we need to consider two things: (1) the identity of the artist and (2) our criteria in viewing global and migratory art which is culturally defined. The tension between theincreased globalization that contributes to migratory practices and on the art belonging to a system that relies on physical and material qualities can be discussed by focusing on the virtual space. It could be suggested that sharing artworks (digital images) online decreases their authenticity. In other words, the main perception is that the artwork needs a material and physical encounter with the audience to create a real experience. It is often suggested that the world outside the virtual one is more tangible and thus more real. However, this would imply a distinction between the virtual world and the ‘real’ world, which some theorists say does not exist. In fact, “there is a reality in virtuality itself” (Wiederkehr González, 2015, p. 213). In other words, virtual worlds can become real places for some people. This virtual world is what Sara Wiederkehr González indicates as cyberspace. Cyberspace is a medium that allows people to stay connected to a reality miles away as “political concerns related to from a distance—geographically—remain a close reality in the virtual world” (Wiederkehr González, 2015, p. 214). This cyberspace provides a space in which discourse about socio-political concerns can be formed and shared, which connexts people across the globe. We argue that virtual spaces are not separate from the real world but rather that these spaces reflect society online.

Now You See Me Moria

Now You See Me Moria (2020) is a photography project initiated by Netherlands-based photographer Noemí to raise awareness about the conditions in refugee camp Moria in Lesbos. The project started after Noemí came across a picture on Instagram by Afghan photographer Amir H.Z., who took photos of the conditions during the COVID-19 outbreak in camp Moria. This inspired her to get in touch with him and start the project, Now You See Me Moria on Instagram.

The project shows photos taken by refugees from within the camp. Certainly, after critique about the extremely poor living conditions in the camp, these photographs are meant to raise awareness and show the activistic standpoint by the artists. The website states,

“Human rights are being violated on a daily basis, journalists and photographers are not allowed to go inside the new camp, NGO staff members are asked not to take pictures. Moria is only one of the many shame spots of a failing European migration policy.” (Now You See Me Moria, 2020)

What is interesting about this case is that the mainstream media has shared pictures from the Instagram account, because journalists were banned from taking pictures inside the camp. Further, art institutions such as Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam have constructed exhibitions showing the photographs and asked designers to redesign the photographs into posters that can be printed and spread throughout the public space. Consequently, we can perceive a flow of images from migrants in the camp, to social media, and from the media to a bigger audience. In this project, identity is constructed by visually portraying daily activities that the migrants participate in during their stay in the camp. Thus, the call for activism is embedded in the visual imagination of the migrant identity in relation to the 'other' and meaning is constructed not in the individual migratory experiences but an overall image of the migrant in inhumane living conditions.

The issues that arise in camp Moria go beyond the individual migratory experience. The migrants encounter comparable problems that connect to larger societal issues regarding migration polities. The migrant identity is not about the individual encounter of certain problems but about a migratory experience that connects to all individuals in the camp. Instead of focusing on the ethnic or socio-cultural properties of identity shaping, this project touches upon the migrant experience as a whole. The migrant identity is made visible at its starting point, namely identity and a nomadic flow throughout (mainly) Europe. “It is almost impossible to define the nature of images without attributing to them the capacity for migration, circulation, reproduction, relocation and cross-cultural translation” (Petersen, 2017, p. 9). In this sense, the images function as a nomadic practice, constituting itself in the media and spreading throughout the world. In this project, activism and engagement become the main focus. This is derived from the notion that the experience of the individuals can make an impact on society.

The activistic tone of the project constitutes it as an intervention in the public sphere. We could say that the flow of the images across media reaches a large audience, the imagery moving from social media to mainstream media and the art institute. The fact that the project is shown in an institutional context, changes the value of the works. The photographs become a work of art rather than a social media post. This could potentially lead to friction between art and the media. Why are those works exhibited in an institute of more value than photographs in the media? Interestingly enough, in this project, the photographs seem to have made that value for themselves. Rarely, photographs that occur on social media platforms find their way into the art institute. This could mean several things, but the most obvious is that conditions about practices like migration need support from a wider audience. This means that the value of the work lies in thecontent and activistic approach, not in the imagery. “The very idea of abandoning or even abolishing the museum would close off the possibility of holding a critical inquiry into the claims of innovation and difference with which we are constantly confronted in today’s media” (Groys, 2013, p. 21). The interplay between art institute and media is important. In projects such as this, it means that we strive for a new understanding of art.

Reconstructing photographs to posters attaches additional meaning towards the presentation of the migrant identity. The photographs, that initially represented the migrant experience from the perspective of migrants, are recomposed by designers who add their own visual language and interpretation. This gives the designers the freedom to magnify the activistic component to the posters and outline the issues that were already visible in the photographs.

In the poster above, different layers are added that contribute to the image shaped by the migrant experience. We see references in style to Ikea, a Swedish store that is well-known and recognized for its affordable furniture. This reference does not only suggest that humane living conditions should be available for everyone, but it also comments on the capitalist society that refuses to provide better conditions for the refugees in Moria. The commercial outings are placed by objects that are used by the refugee that took this picture, provoking the idea that these are 'normal' living conditions in Moria. The visual identity of a big corporation is used could suggest that advertising and capitalism are certainly other big issues in our modern societies. This reflects on the notion of design, recognizability, and the impact of advertising on artistic practices. Lastly, the poster is constructed from a photo taken inside the camp. This values and devalues the work at the same time, keeping in mind that this construction is part of the critique. A photo that has the potential to function as an art object, is reconstructed into a commodity, namely an advertising poster, while at the same time remaining its suggestive power of an art object. The poster is made by established designers, giving it the value and availability to be seen in an institutional context, while, at the same time, function as an object that is meant to be shared in the public space.

Overall, Now You See Me Moria functions on different levels. Different platforms and art forms are used to comment on the inhumane living conditions in the refugee camp, and the project is used to show how art can have an impact on activistic notions and interventions in society. Furthermore, migratory practices are aestheticized by using photographs from within the camp and the constructed posters that follow. The migrant identity that is visualized is not personally connected to the individuals but captures the migrant experience in a larger context, namely that of oppression and poor living conditions. The tension between (social) media and art becomes visible in this project. The nomadic flow of images can increase on a conceptual and aesthetic level how art relates to the migrant identity.

Transgressions - Nalini Malani

In 2017, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam gave Indian artist Nalini Malani a space to share her exhibition Transgressions, which consists of paintings, videos, and what she calls her video/shadow play. Again, this art project is not limited to the public space of the museum, but it can also travel, online due to the increasing accessibility of camera phones (Nail, 2019, p. 61). Visitors share this work online, by taking pictures or videos, as such increasing the visibility by sharing her work on her website. Implications here are that work flows across different media, expanding the work beyond the museum and into the public sphere, similarly to Now You See Me Moria (2020).

For this particular exhibition in the Stedelijk Museum, as well as showing pre-existing works, Malani also created a temporary mural, spanning three by seven meters. She intended it to be a kind of ominous statement. “You have a denuded man, holding the globe, which is half broken and you have the pieces through and on the other side. The people you see, the two large faces, with the staring eyes and the little girl, they all come from a world which is extremely deprived. It is the world of the dispossessed” (Nalani, 2017).

The mural, entitled City of Desires, was erased on the last day of the exhibition. This type of “erasure performance” (Ray, 2020) hints at how memory and identity can be erased. Most of Malani’s work is political as she creates these works from the perspective of a migrant and her personal experiences. She had to flee her country due to the conflicts between India and Pakistan. Her work is full of references to migration, globalization, poverty, and the oppression of women. As discussed above, migratory art differs from media and documentary perspectives about migrants in that it focuses more on a culture that has been transformed by migratory practices rather than presenting migrants as representatives of a minority culture (Petersen, 2017, p. 59). Malani uses her exhibition Transgressions to show the loss of the local culture as a result of globalization. She emphasizes how culture has shifted in such a way that locals feel as though they can no longer build a decent living, without speaking English, even though India originally had six of its own languages, that are seemingly disappearing.

Although Malani is predominantly a painter, most notable in this exhibition are her shadow plays which immerse spectators in the migrant experience. These are works that are created with large, transparent cylindrical shapes, with painted scenes that areaccompanied by videos and sound playing as they slowly spin. The work is full of ecological references, globalization and how the former two ruin certain traditions. “The cylinders depict various scenes, such as two figures (representing India and Pakistan) boxing, the goddess Kali holding the decapitated heads of English colonisers in its many arms, and a Western hunter on an elephant” (Steverlynck, 2017). The artist says she specifically enjoys using different materials because it “helps the language to flow” (Malani, 2017). In other words, she feels it helps to better translate her message to an audience.

As they spin, the cylinders create shadows on the walls of the space. To get the full effect one must stand underneath them. She invites spectators to look at the artworks by creating visually satisfying pieces but on closer inspection, the text provides theartwork a new layer altogether. We see the six Indian languages quite literally disappear into the shadows, as the text moves down the walls. The text “nullifies the beauty” (Malani, 2017) of the original scenes Malani has painted on the cylinders, as they intertwine. She says, “The images begin to speak another language“ (Malani, 2017). Indeed, when we consider the background of what we are truly seeing, the imagery is a hard pill to swallow. It uncovers references to cities being bombed, to the post-colonial past Malani experienced in Indian. This correlates with Groys views on how we need art to reflect on society as a more reliable way to reflect on the individual in contemporary culture (Groys, 2013, p. 182). Malani helps others to understand the position of the migrant by immersing them in the experience. All references to time and space disappear as the spectator is fully enveloped by powerful imagery and sounds.

Identity formation within art does not only connect the recipient to others, it also detects the differences between cultural identities (Petersen, 2017, p. 81). Malani presents this aspect of migratory aesthetics in two ways. On the one hand, by combining local and global culture. For instance, presenting the ramifications of six local languages disappearing she shows the spectator that it is not a simple matter of cultural loss but rather a loss of identity and security. As mentioned before, many Indian people have been led to believe that learning English is their only way to make a life for themselves. Another example are the small references to how big companies have infiltrated regular life in India, such as Orange, the phone provider. A woman’s voice can be heard saying “I speak orange, I speak blue”. It could be argued here that Malani presents the old with the new and thus forms a new identity. On the other, she emphasizes not just parallels between the old and the new but also between different cultures as a whole. A lot of her work is inspired by Greek and Hindu myths. “There are many important parallels in Greek and Hindu myths, which link our cultures” (Malani, 2017). This creates a feeling of universal unity.

Hayv Kahraman

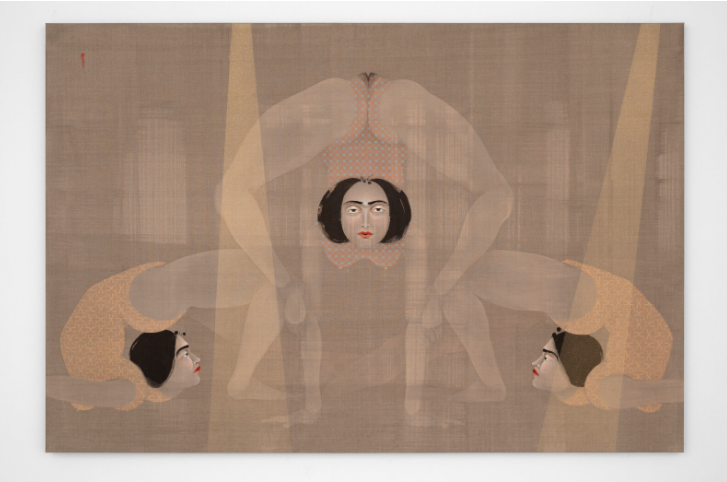

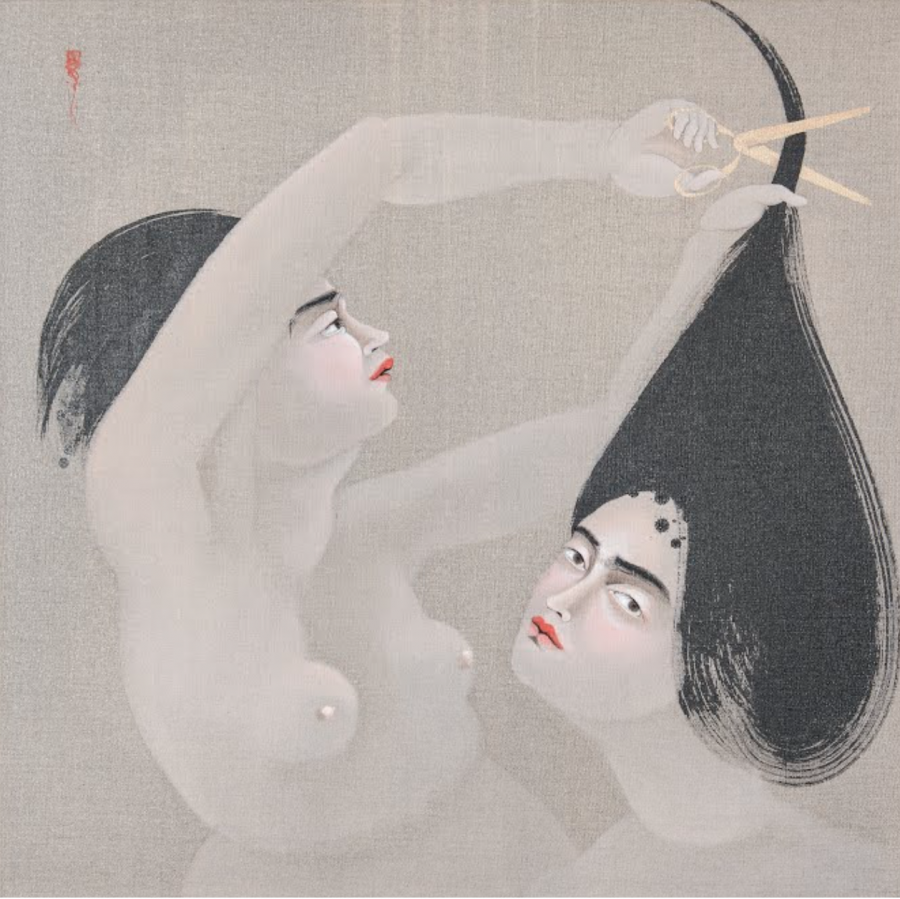

The Iraq-born Hayv Kahraman is an artist whose artworks consist of global stories and cultural aspects. Kahraman fled from the Hussein regime in Iraq as a child and grew up with her family in Sweden. In her work, we find her personal migration story, as the narratives she uses reflect the cultural aspects of Iraq, Sweden, Italy, and her current home, the United States. Kahraman is known for painting women's bodies, with black hair with a focus on the face. She uses techniques learned during her time in Florence, Italy, where she studied graphic design but was inspired by viewing Renaissance paintings in her spare time. She combines these techniques with the Japanese woodcut technique ukiyo-e (Adell, 2019).

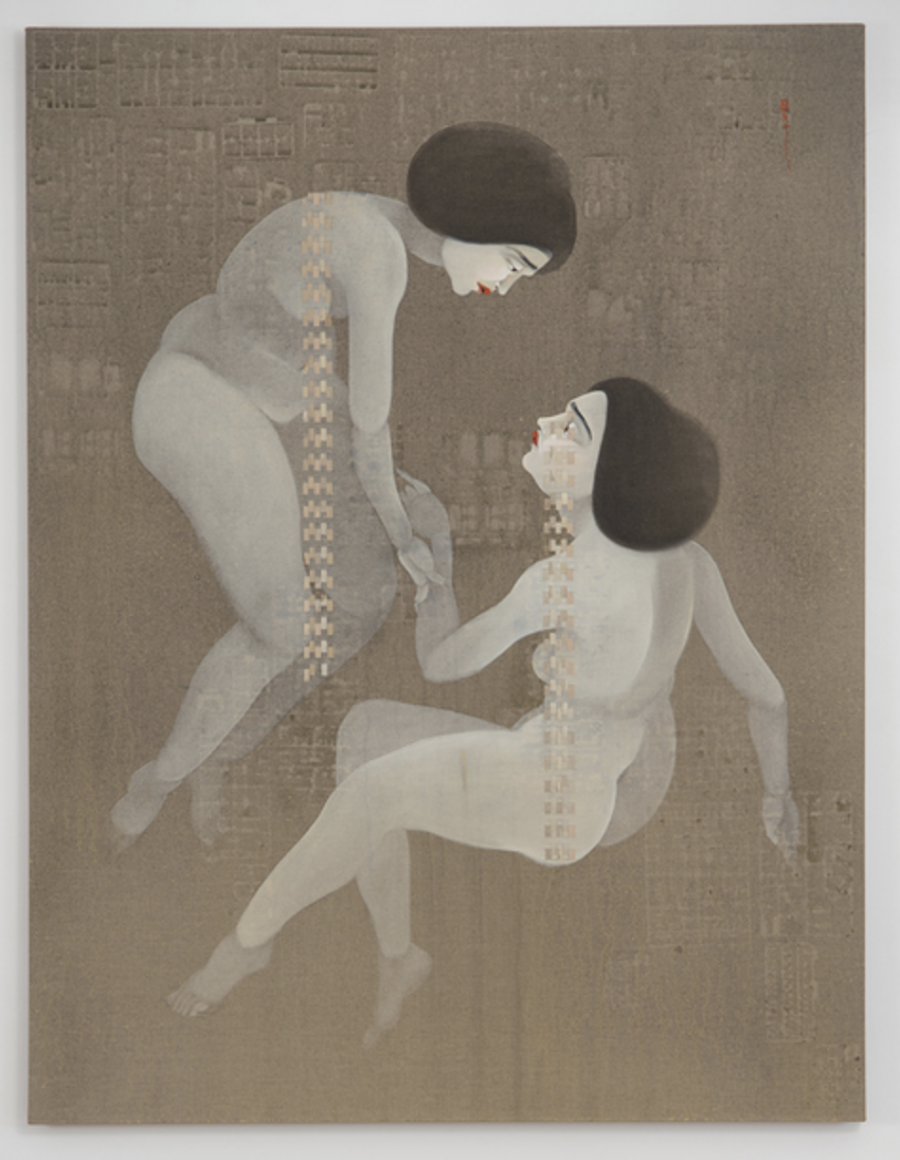

In the exhibition Re-weaving Migrant Inscriptions (2017) at the Jack Shainman Gallery in New York, Kahraman combined the female body with migration. As an 11-year old child in Sweden, Kahraman felt different, she was the ‘other’, the one with a different skin tone and the one with dark hair. In Re-weaving Migrant Inscriptions (2017) we find Kahraman disentangling the female migrant body. In Mnemonic Artifact 1 (2017), we see how she plays with the linen skin, it is ripped off the women’s bodies and is drilled through the painting as a new skin. She creates a new identity, not only for herself but also for the Iraqi and Kurdish women she represents.

Kahraman explains how she felt being a migrant and refugee in Sweden. She felt that her voice had been taken away and no longer had juridical rights She did not feel human. The only thing she had control over was her body. Her body became a way of resistance. It became her voice to speak against the systemic structure of power that held her down (Del Barco, 2019). The female bodies in her work are references to herself, as she wrote in the Journal of Middle East Women's Studies: “I pose in the nude and photograph my body to use as outlines for paintings. My figures then are visual transitions of my own body. The figures are rendered to fit the occidental pleasures. White flesh. Transparent flesh. Posing in compositions directly taken from the renaissance. Conforming to what they think is ideal” (Kahraman, 2015).

Kahraman tries to empower female and migrant bodies. We see how she shapes identity by giving new meanings to the bodies in her work. In her paintings, we see figures with black hair and a pale and sober body. The most detailed parts of her work are the faces yet they lack expression. Female body parts, such as breasts and vulvas are shown. At the academy in Florence, she admired the work of Renaissance painter Botticelli, and she examined how he painted women. However, she found out how these depictions were 'colonized' by the male, Eurocentric gaze, which led her to critique power-hegemonies (Ray, 2017). In Not Quite Human 1 (2019), we see how Kahraman painted contortionists. Kahraman explains how she felt that most existing pictures of female contortionists have sexual intentions. By focusing on the gaze and the face of the woman, who is staring right at the viewer, there is a shift of power. The artist explains: “They're essentially bending backwards, it's a very submissive act. It's very violent... but there is a power there. She's returning the gaze. She knows that is what you want her to be. And she's giving it to you....There's a subversion there within the gaze” (Del Barco, 2019).

In an interview with The Art Newspaper (Finkel, 2018), Kahraman explained how she saw Kurdish refugees portrayed on television, but framed as poor. From that moment she started questioning: “How do we mediate images in these humanitarian campaigns, these images of 'suffering others', in a way that doesn’t strip them of all their dignity and in a way that allows them a voice?” (Finkel, 2018). With this question we see how Kahraman participates in the migration debate. We have seen how some of the most shared and viewed images of the past few years have been digital images of migrants (Nail, 2019, p. 61). How those images are framed and perceived is important. The image of the poor living circumstances in Moria is not the only perspective on migration. Kahraman goes beyond the issues of the day with her work. Her work changes the perspective of bodies, migrants, women, and cultures. Her art transcends mundane and routine perception, she compresses experience by conjoining complex social and psychological stimuli, as that is the power of art (De la Fuente 2007, p. 419).

Kahraman's work consists of global cultural stories. Just like Malani, she combines different cultures and mythologies and merges them into her art. In the series To The Land of the Waqwaq (2019) Kahraman used stories of Hawaiian mythology and combined that with stories she heard when living in Iraq. The Hawaiian story of the goddess Kapo, who threw away her detachable vagina to save her sister from being raped, was combined by Kahraman with the story her mother told as they were fleeing from Baghdad. In this story called To The Land of the Waqwaq, the characters fleeing to the ‘Shangri La’. In this, Kahraman’s work can therefore be categorized under migratory aesthetics since its focus is more on how culture has been transformed by migratory practices rather than presenting migrants as a minority culture (Petersen, 2017, p. 59). She gives migrant bodies a new global identity. Further, in the story, To The Land of the Waqwaq (2019), we see how a woman cuts the hair of another woman. Cutting hair can already be seen as an act of self-empowering, as you not only control your own body but also your identity. Another component in To The Land of the Waqwaq, is of a woman who hangs naked in a tree, ready to be cut by any man passing by, who then gets permission to do whatever he wants with her. By interlacing the story of Kapo, Kahraman creates a different perspective of the patriarchal narrative, told in Iraq. Kahraman closes the gap between the individual and the other that Groys (2013) discussed. Because of imagination, we can see things from Kahramans perspective through her artwork however, she understands the perspective of the other, because she is in a position to understand the perspective of the viewer. Kahraman understands how migrants have been portrayed in the media and changes this perspective. She was that refugee or the 'other', shown in the media.

Furthermore, Petersen argues: “We need to find ways to deconstruct the misconception that the artist’s ‘authentic’ ethnic roots and cultural identity are always the prime sources of the work’s meaning” (2017, p. 81). Although we see that Kahraman’s work is often based on her ethnic roots and identity, as seen in both To The Land of the Waqwaq and Mnemonic Artifact, her work shows us global aesthetics. She uses different techniques and combines different art styles, creating a new meaning of art. The materiality of an artwork always intervenes in the conceptualization of the work, because the materiality is one of the resources through which cognitive and aesthetic experience of encountering a theme, such as migration, is enriched (Bal & Hernández-Navarro, 2011, p. 9-20). We see that migration has gained attention in representation in art. This is because of the adaptability of the work of art concerning the mobility of images (Petersen, 2017, p. 2). Kahraman uses the migrant identity as a contextual frame to show the connection between art, migration, and societal engagement. In this way, her migrating experience is inherently visible in her work.

However, the term migration is dual according to Petersen: “Every immigrant who arrives as a newcomer from the point of view of the receiving country is, at the same time, an emigrant from the perspective of those who stayed behind in the home country” (Petersen, 2017, p. 5-6). In the case of Kahraman, who lived in Iraq, Sweden, Italy, and the United States, her migration background is diverse. Like her artwork, she herself is not just an immigrant or emigrant subject. The multiculturalism in Kahramans’ art, can therefore be considered as the by Christensen (2017) coined term post normative cosmopolitanism:

"Through experimental forms of art practice, displaced or abject subjects are capable of reimagining place and identity. They move from the unhomely to the homely, but in such a way that place and homeliness are perpetually fluid and forgiving. In that sense, they have helped transform multiculturalism into what Miyase Christensen calls “post normative cosmopolitanism” (Christensen 2017, p. 555). Today, our ties are no longer just local or even national, but global, and we increasingly consider ourselves part of the world at large" (Papastergiadis & Trimbol, 2019, p. 38-53).

Kahraman focuses on migrant bodies and migrant identities and uses her migratory narrative in her work. She combines this with global themes and cultures, making her work an example of how migratory aesthetics can be applied to political and societal issues. Kahraman not only controls her own voice but stands for migrants worldwide. She knows how to use art as an act of resistance against the hegemonic system, as she manifests artistic practices aiming to give a voice to all those who are silenced within the framework of the existing hegemony (Mouffe, 2007, p. 5).

The migrant identity can be approached from many different angles. Artists who use migratory practices in their work all have a different background and experience, which in turn shapes the way their work - and the migrant experience - is perceived on a larger scale. No migrant is the same, which Malani’s Transgressions, Now You See Me Moria, and Kahraman’s work has shown in varying degrees. Each of these projects shows us that migratory art differs from media and documentary perspectives about migrants. Namely, these art projects show examples of how culture has transformed by migratory practices rather than presenting migrants as representatives of a minority culture.

In all three cases, the aesthetic components of the migrant experience become visible. We have seen in Now You See Me Moria, that migrant art can provide an activistic stance against the policies that are becoming more and more problematic. In this case, globalization is used to create an exchange between migrants, artists, and the spectator. We can see that artistic practices have the capacity to translate problematic issues into an aestheticized image that can reach a broader audience and bring awareness. The migrant identity as such is no longer based on the individual experience of the refugees but rather on a collective migratory experience and a need for change. Regardless of the image that has been established by the media, the artistic layers create understanding and friction between the migrant image and socio-political issues.

The works of Nalini Malani materialize the personal migratory experiences of the artist towards the spectator. She shows us that we must continue to look beyond our first impressions to see the full extent of what is going on in the world. Rather than just telling us that Indian culture has been transformed by globalization and its ramifications, she visualizes it through her video/shadow plays. Malani’s work comments on global/local discourses, while her work becomes part of the flow of images. The work is immersive and visually strong, and can thus use migratory aesthetics as part of the message she wants to convey; that the migrant experience is loaded with meaning, and shifts from a personal story to a universal understanding.

Hayv Kahraman shows us that migrant art can connect the migrant experience to larger, but comparable issues. By translating her personal migratory experience to feminism, she creates a narrative that uses (his)stories to reflect on problems within society. The use of the female body reflects on the position of the migrant as an outsider in society, and comments on the notion of ‘belonging’. Kahraman shows us that migration can lead to a nomadic existence in which borders do not define a person’s identity.

The migrant experience is no longer a personal experience but engages with many socio-cultural and political issues in our contemporary society. Migration can be understood as the “only phenomena that radically differentiates our era from the nineteenth century” (Groys, 2017) because it captures many aspects of identity formation. Furthermore, as we have explained, migratory art has the capacity to address various layers of the migrant experience, among which: activism, globalization, belonging, and feminism. This layered approach to one of the largest issues in society shows us that art can use its aesthetic components to overcome categorization and translate an experience into a universal story for those that struggle to recognize their narrative in the media.

References

Adell, A. (2018, March). Hayv Kahraman, body as a container of diasporic memories.

Bal, M., & Hernández-Navarro, M. Á. (2011). Art and Visibility in Migratory Culture : Conflict, Resistance, and Agency. Editions Rodopi.

Bem, M. (2021, March 5). Door de ogen van een vluchteling in Moria. De Volkskrant.

Christensen, M. (2017). Postnormative cosmopolitanism: Voice, space and politics. International Communication Gazette, 79(6–7), 555–563.

De la Fuente, E. (2007). The ‘New Sociology of Art’: Putting Art Back into Social Sciences. Cultural Sociology, vol. 1, no. 3, 2007, pp. 409–425.

Del Barco, M. (2019). Iraqi American Artist Hayv Kahraman Is 'Building An Army Of Fierce Women.

Finkel, J. (2018, September 2021). Hayv Kahraman on the Kurdish exodus—and the trouble with humanitarian campaigns. From The Art Newspaper

Groys, B. (2013). Art Power. The MIT Press.

Kahraman, H. (2015). Collective Performance: Gendering Memories of Iraq Hayv Kahraman in Journal of Middle East Women's Studies, Volume 11, Number 1, March 2015, pp. 117-123 (Article) Published by Duke University Press.

Kahraman, H. (2017). Mnemonic Artifact 1 [Painting]. Shainman Gallery, New York, United States of America.

Kahraman, H. (2019). Not Quite Human 1, [Painting]. Jack Shainman, New York, United States of America.

Kahraman, H 2019b. To the Land of the Waqwaq I [Painting]. Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture and Design, Honolulu, United States of America.

Malani, N. (2001). Transgressions [Video/shadow play installation]. Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam, NL.

Malani, N. [Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam]. (2017, 23 mei). NALINI MALANI - TRANSGRESSIONS [YouTube]

Mouffe, C. (2007). Artistic Activism and Agonistic Spaces. Art & Research, 1(2).

N. (2020). Now You See Me Moria.

Nail, T. (2019). The Migrant Image. In Handbook of Art and Global Migration (pp. 54–70).

Papastergiadis, N. & Trimboli, D. (2019). From Global Turbulences to Spaces of Conviviality. In B. Dogramaci & B. Mersmann (Ed.), Handbook of Art and Global Migration (pp. 38-53). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.

Petersen, A. (2017). Migration into art: Transcultural identities and art-making in a globalised world. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Ray, S. (2017, November 26). An Iraqi Artist Bears Witness to the Trauma of Displacement.

Ray, D. (2020). Art without borders – an interview with Nalini Malani. Apollo Magazine.

Steverlynck, S. (2017). Nalini Malani Transgressions. ArtReview Asia.

Wiederkehr González, S. (2015). Migration, Political Art and Digitalization. In Digital Environments (pp. 211–225).