What do 'Napalm Girl' and Alan Kurdi tell us about the digital public sphere?

With the rise of digital media, common citizens play an increasingly large role in the public sphere. However, these new voices are often based on emotions rather than rationality. Ideally, we would create a public sphere that works with both.

'Napalm Girl' and Alan Kurdi in the Public Sphere

A little girl, surrounded by soldiers, running away from a cloud of napalm that has burned her clothes and patches of skin off her tiny body. The photograph of the ‘Napalm Girl’ (Phan Thi Kim Phuc) was shot on June 8, 1973, by Associated Press photographer Nick Ut and was published globally the next day. Today, the image is perceived as an icon of the horrors of the Vietnam War specifically, and the horrors of war in general. Moreover, it is considered as one of the most recognized photos in American photojournalism (Hariman & Lucaites, 2003, p. 39).

Years later, in 2015, a little boy laying face-down on the Turkish shore shocked the world as his picture spread globally not only by means of traditional media, but mainly by means of social media such as Facebook and Twitter. It can be stated that the photo of Alan Kurdi, taken by journalist Nilüfer Demir, became the symbol of the horrors of the Syrian refugees as they try to reach Europe in search for a better life.

Despite the similar tragic nature of both, the ways in which these pictures were spread around the world are significantly different. In the 1970s, there was no such medium as Twitter; the main conveyers of news were traditional media such as newspapers and television. However, since the appearance of social media, a shift from traditional media to digital media took place. This also resulted in new power relations (Josephi, 2016) and new roles for emotionality and rationality within the media industry and the public sphere (Wahl-Jorgensen, 2016).

We are now confronted with the clash of power between political leaders and common citizens, and with a shifting importance of emotionality and rationality. Because of the similarly emotional content of the two photos and the different (technological) time periods in which they were published, discussing these pictures and their impact side by side can lead to deeper insights into the changing nature of the media and transforming power relations in the media and public sphere. How do the pictures of Phan Thi Kim Phuc and Alan Kurdi contribute to our understanding of the changing nature of the media? What do they tell us about who holds the power in the public sphere and the media?

From traditional media to participatory media

The Vietnam War is often considered to be the first television war (Hariman & Lucaites, 2003, p. 39). The incorporation of media into the war led to conflicts between the media and the American government. The media presented a rather contradictory, negative image of the war compared to the positive portrayal the war officials wanted to convey. To the disappointment of the government, the view of the journalists became the main influencer of the public’s opinion and led to public protests, which eventually contributed to the end of American involvement in Vietnam (Hallin, 1989, pp. 3-4).

The development of social media has opened the door for the common citizen who seeks to participate in the creation and distribution of news – a role that was confined to journalists and media houses during the Vietnam War.

However, because of the media’s impact on the Vietnam War, the government of United States, as well as authorities of other countries, concluded that there should be tight controls over the media coverage of wars. For instance, the British government decided to control the news coverage of the Falkland crisis in 1982. Also, in 1983, the American government did not allow the media to cover the opening phase of the invasion of Grenada (Hallin, 1989, p. 4).

In times of social media, however, it becomes harder for governments to control the flow of news items. The authority of professional journalists and media houses has also changed . The development of social media has opened the door for the common citizen who seeks to participate in the creation and distribution of news (Josephi, 2016, p. 9) – a role that was confined to journalists and media houses during the Vietnam War.

Nowadays, we see alternative news websites contesting the perspectives of mainstream media and/or sharing what is ignored by them, and citizens retweeting (alternative) news items, commenting on articles, creating their own (news) blogs and websites, sharing their news-related photos and videos taken with their (smartphone) camera, etc. Because of digital media, the common citizen can become what Josephi (2016, p. 17) calls the ‘entrepreneurial journalist’, a person ‘who can act as a supplier directly to the consumer or whose work is aggregated into a larger website.’

Especially Twitter has transformed traditional journalism with its one-way nature into participatory journalism. Even though tweets are not the same as journalism, they can function as journalistic acts (Josephi, 2016, p. 18). After the photo of Alan Kurdi was published, it was shared and discussed on many social media websites.

Figure 1

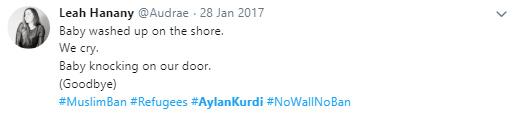

Even a few years later, the Alan Kurdi case is still used for addressing different issues. For instance, on Twitter, Rohingya Vision shared an article concerning the conflict between the Rohinya people and Burma with a disturbing picture of a dead Rohinya boy as a result of a shooting. Interestingly, this post contains the hashtag #AylanKurdi (figure 1) in order to address the innocence of children in war.

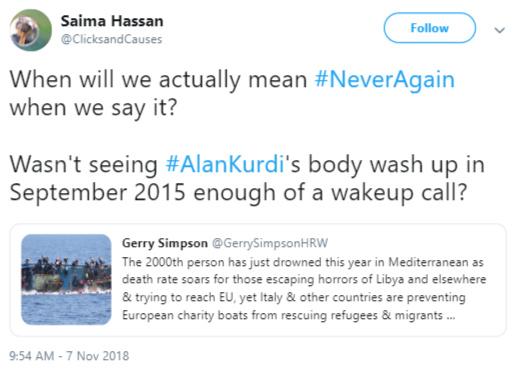

Figure 2

Other citizens and/or alternative news sites use the hashtag #AlanKurdi to criticize the European Union's refugee policies (figure 2) or even Trump's Muslim ban and his wall on the border of Mexico and the United States (figure 3). Erdogan's regime has also been addressed by using the hashtag (figure 4). These instances illustrate that citizens and (alternative) news sites form an open online discussion about a diverse range of conflicts around the hashtag #A(y)lanKurdi and criticize the policies of several political leaders.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Rationality and emotionality

A concern of the digitalization of the media is that sentiments have entered digital journalism, especially through social media (Josephi, 2016), such as we have seen in the figures above. Emotional expression and engagement are central to digital media and often undermine the rationality of the public sphere (Wahl-Jorgensen, 2016).

Philosophers working in the 'modern' paradigm are worried about the emotional content in the public sphere. They are concerned that if the public sphere is controlled by visual, emotional, and personal communications instead of logical, restrained, and literate communications, it becomes sensitive to (Fascist) domination. On the contrary, ‘popular’ or ‘post-modern’ philosophers believe that the control of the public sphere by logic will lead to (Fascist) oppression (McKee, 2005, p. 114).

The fact that the attack was done by Vietnam and not the United States did not change the most important fact the public already knew: that the United States was waging a war ‘without purpose, without legitimacy, without end’

Emotive news items already appeared during the Vietnam War. The story of the ‘Napalm Girl’ photo was not solely based on facts. In some reports, the picture was described as an ‘accidental napalm attack’ by the US forces, even though the attack was carried out by South Vietnamese troops. What is more, the girl was directly taken to the hospital (Hariman & Lucaites, 2003, p. 40).

Still, we miss the point if we only focus on these factual details. The fact that the attack was done by Vietnam and not the United States did not change the most important fact the public already knew: that the United States was waging a war ‘without purpose, without legitimacy, without end’ (Hariman & Lucaites, 2003, p. 41).

Moreover, whereas the newspapers told the public what was happening in Vietnam, the photo stirred the public consciousness of morality; it was not merely about the wrongs of the United States, it was also greatly about the immorality of the Vietnam War and war in general. As Hariman & Lucaites (2003, p. 40) state, ‘[t]his iconic photo was capable of activating public consciousness at the time because it provided an embodiment transcription of important features of moral life, including pain, fragmentation, modal relationships among strangers, betrayal and trauma.’ This indicates that the photo was able to wake up the public concerning a serious and real problem – something a text that adheres to the norms of rationality may not be able to do so as successfully.

Psychological research has shown that images have a greater impact on people than statistics (Slovic et al., 2017, p. 1). After the publication of the Alan Kurdi photo, individual aid and refugee policy changes occurred in numerous countries. For instance, the daily donations to the Red Cross increased 100-fold in the week after the publication (Slovic et al., 2017, p. 2).

Image enters politics

Not only citizens were touched by the photo, also politicians reacted. Former French president Hollande phoned several European leaders and Erdogan to tell them that the picture must be a reminder of the world’s responsibility towards refugees. ‘If the picture went viral around the world, it must also get a round of responsibilities […] I think about all the victims that are never photographed, and the future victims if we do nothing,’ he said.

What is more, for 5 years, the Obama administration did not react to the horrific statistics of Syria concerning over 400,000 deaths, hundreds of thousands of people at risk from regime sieges, and 12 million displaced people (Slovic et al., 2017, p. 1). But at the Summit on Refugees of the United Nations in 2016, former US president Obama referred several times to Alan Kurdi and advocated for action:

‘That little boy on the beach could be our son or grandson. We cannot avert our eyes or turn our backs. To slam the door in the face of these families would betray our deepest values. It would deny our own heritage as nations, […] that we have been built by immigrants and refugees. And it would be to ignore a teaching at the heart of so many faiths that we do unto other as we would have them do unto us; that we welcome the stranger in our midst.’

He ended his speech with the words:

‘We spend, so many of us in politics and leadership, so much time devoted to ascending the ladders of power. We spend time maintaining it; we spend time trying to win over public opinion. And maybe sometimes we forget that the only rationale for doing it is to help that little boy. I hope and pray that we remember.’

Statistics cannot stir feelings of empathy like images can. Still, the effect of the photo did not hold sway. The lack of political solutions led to little progress in stopping the rising death numbers and fleeing people. Also, five weeks after the publication, the number of individual donations dropped back to the same number as before the photo was published (Slovic et al., 2015). Psychological research shows that seeing only one person in distress stirs a greater response than seeing more individuals in distress. For example, people are less likely to donate money when they see more than two people (Slovic et al., 2017, p. 3).

Ideally, we need a balanced public sphere; one in which rationality and emotionality work together instead of fight each other

This raises serious questions about the increase of emotive content in digital journalism and the role of social media in journalism. For example, Twitter’s content is mostly emotional and personal; whether it is about an accident or someone’s death, Twitter responds in an emotive manner (Josephi, 2016, p. 18). As many people get their news from Twitter, this means we see more and more pictures that are meant to make us feel a certain way.

We increasingly see pictures of people in distress – people starving, bleeding, crying, dying. According to psychological research, seeing a lot of people in distress will increasingly make us react in a rather neutral manner. Following this thought, Twitter suffers from an excess of emotion because it will not lead to action.

Journalist Richard Littlejohn argues in his opinion blog This child’s death was tragic but not our fault for the Daily Mail that ‘the shocking death of a child should never be exploited just because media tarts and ‘liberal’ luvvies […] can feel good about themselves. However terrible, however tragic such cases are, they’re not a sensible basis for realistic asylum policy.’ Similarly, journalist Brendan O’Neill writes in his blog Sharing a photo of a dead Syrian child isn’t compassionate, it’s narcissistic for The Spectator that ‘showing dead kids is, in my mind, emotionally insensitive. It can be cruel and unnecessary. It’s the victory of the visceral over the rational. And we really need a rational debate about the migrant crisis, rather than people holding up a dead-child snuff photo and saying: ‘I cried, therefore I’m good.’’

These journalists, however pessimistic and partisan, do have a point. Only emotions and terrible images will not lead to a rational debate, which we need in order to accomplish effective policy making. But the mistake they are making is perceiving reason as the polar opposite of emotion and the visual.

The cases of Phan Thi Kim Phuc and Alan Kurdi illustrate that pure rationality (statistics, texts adhering to the established norms of rationality, etc.) in the public sphere cannot wake us up and arouse empathy in us the way emotive images can – something we do need to motivate us.

However, as soon as empathy is aroused, we need rationality to make sense of our feelings and take serious humanitarian action that lasts for longer than five weeks. This will not happen in a public sphere in which people mainly receive news through emotional content, nor will it happen in a public sphere that dismisses emotions.

Ideally, we need a balanced public sphere; one in which rationality and emotionality work together instead of fight each other. As Slovic et al. (2017, p. 4) stated, we need to be able to turn to strong political international institutions and laws for support once empathy has been awakened. In reality, such laws and institutions do not exist as of yet. The Genocide Convention and the Responsibility to Protect have barely been active. The UN, the main institution that should coordinate interventions worldwide, is often stopped because of vetoes from members of the Security Council who operate in their own interests (Slovic et al., 2017, p. 4).

The politicians who said they wanted to change the situation of the refugees did not take enough action either. Death tolls of refugees and migrants increased whilst they tried to reach Europe and several southern and eastern European countries closed their borders in 2016. This means we should not overestimate the power of images in the media and public sphere.

Emotion and the digital public sphere

The entering of social media into journalism has given common citizens more power in the media and the public sphere. Politicians cannot stop the flow of information like they could before the existence of the internet. Both the picture of Phan Thi Kim Phu as the picture of Alan Kurdi show that emotionality is more effective in stirring empathy than purely rational information. Also, they both illustrate that we can critique and fight politics through images.

However, the increase of citizen power also led to more emotional content in the media. Examples of the hashtag #A(y)lankurdi has shown that citizens and (alternative) news outlets can critique all kinds of socio-political issues. The downside of this change is that social media, especially Twitter, produce an excess of emotionality. This is a problem, because it can lead to neutral feelings within readers, which will not lead to effective action.

Moreover, Twitter is used as a news source by many people and does not contribute to a healthy public sphere in which we have a productive, balanced public debate. Both citizens and politicians need good international institutions and laws so we can all transform our empathy into action. The voices of the citizens have become louder in the times of social media, but in the end, political powers still dim these voices by holding the deciding power in their hands. We need new, progressive ways, and the will to find the balance.

References

Hallin, D. (1989). The ‘’Uncensored War’’: The Media and Vietnam. University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles, California.

Hariman, R. & Lucaites, J. (2003). Public Identity and Collective Memory in U.S. Iconic Photography: The Image of ‘’Accidental Napalm’’. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 20(1), pp. 35-66. DOI: 10.1080/0739318032000067074.

Josephi, B. (2016). Journalism and Democracy. In T. Witschge, C.W. Anderson, D. Domingo & A. Hermida (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism (pp. 9-24). SAGE Publications Ltd.

McKee, A. (2005). The Public Sphere: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Slovic, P., Västfjälll, D., Erlandsson, A. & Gregory, R. (2017). Iconic photographs and the ebb and flow of emphatic response to humanitarian disasters, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), 114(8), pp. 1-5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1701230114.

Wahl-Jorgensen, K. (2016). Emotion and Journalism. In: T. Witschge, C.W. Anderson, D. Domingo & A. Hermida (Eds.), SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism (pp. 128-143). SAGE Publications Ltd.