Shia LaBeouf’s metamodern subversions of authenticity

A few years ago, while mindlessly scrolling though my Facebook feed, I stumbled upon an article entitled: ‘What the hell is going on with Shia LaBeouf?’. The man in question turned out to be an actor who was apparently, like so many of his Hollywood colleagues, spiraling out of control.

Who is Shia LaBeouf?

After clicking on the article my entire feed was filled with articles and stories about LaBeouf, as is the usual way of things on Facebook. So in subsequent months, Facebook kept me up to date with the latest developments in LaBeouf’s life and with his public performances. These became more confusing as time went by and I noticed that LaBeouf was consciously undermining his own credibility and sabotaging his 'authenticity'.

I couldn’t quite put my finger on these performances until I found out that LaBeouf had joined a performance-art collective inspired by a cultural philosophical stream of which I had not heard up to that point: Metamodernism. Therefore, if we want to understand LaBeouf’s performance art in general, and his subversions of authenticity in particular, Metamodernism should be taken into account

This paper aims to do precisely that.

First, the story of LaBeouf will be told as it was brought in the media.

After that, the cultural philosophy of Metamodernism will be explained and special attention will be paid to the concept of authenticity.

Finally, I will give a reading of some of LaBeouf’s artistic performances in order to answer my main research question: taking his affiliation to Metamodernism into account, how does Shia LaBeouf approach and subvert the concept of authenticity in his performance art?

The story of Shia LaBeouf

When Hollywood actor Shia LaBeouf made his directing debut in 2012, the press was positive. LaBeouf’s short film Howard Cantour.com, in which we follow the eponymous online film critic Howard Cantour, was lauded. Indiewire wrote: “Labeouf’s memorable short is ultimately a surprisingly successful movie on the experience of watching a movie that should only serve to encourage Labeouf to further test the directorial waters”. It seemed as if Labeouf had successfully branched out from his reputation as a blockbuster movie star into the world of directing.

Yet soon after the online release of Howard Cantour.com on December 17, 2013, Buzzfeed pointed towards a peculiar resemblance with Daniel Clowes’ Justin M. Damiano, a comic that was published in 2007. The movie’s script turned out to be a near scene-for-scene replica of Clowes' comic. LaBeouf’s first steps in the directorial waters had been nothing but an act of plagiarism.

Clowes responded with surprise: “The first I ever heard of the film was this morning when someone sent me a link. I've never spoken to or met Mr. LaBeouf. I've never even seen one of his films that I can recall — and I was shocked, to say the least, when I saw that he took the script and even many of the visuals from a very personal story I did six or seven years ago and passed it off as his own work. I actually can't imagine what was going through his mind."

Labeouf himself responded with a series of tweets in which he expressed, what seemed to be, authentic and sincere remorse:

In my excitement and naiveté as an amateur filmmaker, I got lost in the creative process and neglected to follow proper accreditation

— Shia LaBeouf (@thecampaignbook) December 17, 2013

I deeply regret the manner in which these events have unfolded and want @danielclowes to know that I have a great respect for his work

— Shia LaBeouf (@thecampaignbook) December 17, 2013

I was truly moved by his piece of work & I knew that it would make a poignant & relevant short. I apologize to all who assumed I wrote it.

— Shia LaBeouf (@thecampaignbook) December 17, 2013

Yet that same day, he also posted a tweet that seemed to justify his actions:

Copying isn't particularly creative work. Being inspired by someone else's idea to produce something new and different IS creative work. — Shia LaBeouf (@thecampaignbook) December 17, 2013

Once again it was BuzzFeed that shed light on the issue and pointed out that LaBeouf had plagiarized this last apology from a Yahoo! Answers section regarding the question “Why did Picasso say “good artists copy but great artists steal?”.

This proved to be the start of a plagiarism frenzy on LaBeouf’s part as in the following days he plagiarized the public apologies of golfer Tiger Woods, Republican politician Robert McNamara, rapper Kanye West, visual artist Shepard Fairey and Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

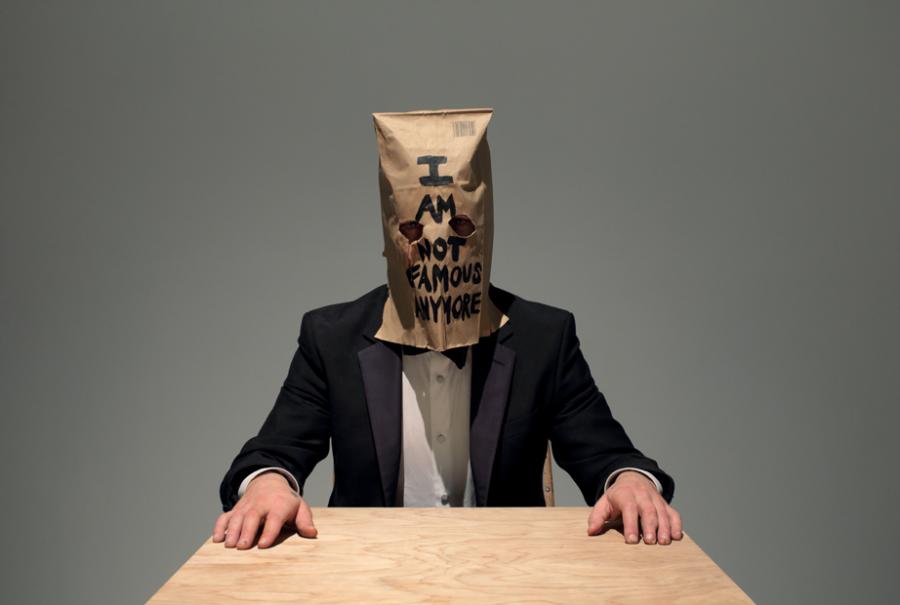

Although his Twitter behavior was frowned upon, many thought that this was simply an actor who responded to the public outcry with irony. It was not until LaBeouf’s appearance at the 2014 Berlin Film Festival that the media started to speculate about a meltdown of the former Disney star. LaBeouf, in Berlin to attend the premiere of Lars von Trier’s Nymphomaniac, walked the red carpet with a paper bag over his head reading: “I am not famous anymore”.

One day later, during a press conference for Nymphomaniac, LaBeouf seemed intoxicated and left the stage after delivering the cryptic line: “When the seagulls follow the trawl, it is because they think sardines will be thrown into the sea.” Journalists were quick to point out that LaBeouf had pulled another plagiarism stunt, this time plagiarizing the words (and gestures) of former Manchester United player Eric Cantona who delivered them during a press conference after his conviction for assault in 1995.

The media was left perplexed: LaBeouf did not seem to care about his authenticity in the eyes of the public anymore and appeared to be on a crash course to destroy the last bit of credibility he still enjoyed. LaBeouf was, like many of his fellow Hollywood colleagues, spiraling out of control.

But the story took another turn when LaBeouf tweeted that his life was ‘performance art’. In addition, LaBeouf declared his allegiance to a Metamodernist manifesto and a few days later it was made public that he had teamed up with two fellow Metamodernist artists, Nastja Rönkkö and Luke Turner. This put his acts of plagiarism in a different light: was LaBeouf’s intentionally inauthentic behavior perhaps part of a broader artistic statement, and if so what was this statement? In order to answer these questions, we first have a closer look at what LaBeouf and his colleagues understand by Metamodernism.

Some ‘Notes on Metamodernism’ and authenticity

Metamodernism was introduced to the world by the Dutch cultural philosophers Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker in 2010. In their article ‘Notes on Metamodernism’ (2010), they aimed to describe an emergent ‘structure of feeling’, or ‘sensibility’ called Metamodernism; a ‘sensibility’ that can shed light on “current affairs and contemporary aesthetics that are otherwise incomprehensible” (Vermeulen & van den Akker 2010: 2).

Essential to understanding Metamodernism is that it is very much tied to a particular period in time and therefore, to a particular generation. This millenial generation – also sometimes referred to as the e-generation – grew up in the 80’s and/or 90’s and is therefore, Vermeulen and van den Akker argue, a child of postmodernism. As such, this generation was readily equipped with what one could call the postmodernist toolkit. This toolkit consists, among others, of a strong dose of irony and sarcasm, a sense of societal detachment and an inclination towards cultural, social and political deconstruction.

Yet according to Vermeulen and van den Akker, the period of postmodernism has ended, and a new cultural dominant has manifested itself: Metamodernism. This cultural sensibility finds itself (ontologically) in between modernism and postmodernism, in the sense that it oscillates between - what Vermeulen and van den Akker call - the naivety and positive idealism of modernism on the one hand, and the ironic detachment of postmodernism on the other. The Metamodern attitude can therefore be conceived of as an “informed naivety”, or a “pragmatic idealism”: informed by your (postmodern) distrust, you realize that your idealism is naïve yet you consciously suspend your belief in this realization and nonetheless strive to fulfill your ideals. As Vermeulen and van den Akker explain:

“The current, metamodern discourse also acknowledges [like the postmodernist discourse] that history’s purpose will never be fulfilled – indeed, because it does not exist. Critically, however, it nevertheless takes toward it as if it does exist. Inspired by a modern naïveté yet informed by postmodern skepticism, the metamodern discourse consciously commits itself to an impossible possibility.” (Vermeulen & van den Akker 2010:5)

It is this informed yet equally naïve oscillation, this uneasy negotiation between the modern and the postmodern that lies at the heart of Metamodernism.

But after reading the above, one may rightfully ask how Metamodernism actually manifests itself in cultural society; what are its themes and tropes?

In the first place, Vermeulen and van den Akker point towards the return of big stories; the return to the ‘grand récits’ (Vermeulen & van den Akker 2013). No longer do we (read: milennials) feel the need to deconstruct the big narratives and ideologies of the past, like postmodernists did. This however does not mean that we have slipped back into ‘modern’ enthusiasm or naivety. Instead, we supplement our (modernist) idealism with a (postmodern) skepticism: big narratives are told but there exists an awareness of the dangers that can lurk within them.

Secondly, Vermeulen and van den Akker note a strong willingness in the current generation to change society; to dream about the possibilities that the future holds (Vermeulen & van den Akker 2013). Spurred by the realization that the world is facing several (existential) crises (such as the financial crisis, the ecological crisis and the migration crisis), a utopian longing has evolved to make the world a better place and to become socio-politically engaged. This all in spite of the acknowledgement that their efforts will be doomed to fail.

"The metamodern sensibility oscillates between a modern enthusiasm for authenticity and a postmodern 'sense' about athenticity's artificiality."

Lastly, Vermeulen and van den Akker distinguish sincerity and affect as two dominant themes of contemporary culture (Vermeulen & van den Akker 2013). There is a certain longing among artists, intellectuals but also youngsters at large, for ‘honest’, ‘true’ and sincere personal experiences on the basis of empathy. This is coupled to the socio-political engagement and the return of grand narratives that were discussed before: the millennial generation is looking for sincere and honest engagement in order to improve the world.

Closely related to sincerity and affect is the trope of authenticity. As Charles Lindholm explains, authenticity is “the leading [more spiritual] member of a set of values that includes sincere, essential, natural, original and real” and we are witnessing a “global quest” for it (Lindholm 2008: 1). Even though Vermeulen and van den Akker do not mention it explicitly, it fits perfectly in the Metamodern narrative for it seems to be an unrealizable ideal in spite of all our efforts to attain it: “the metamodern sensibility” oscillates “between a modern enthusiasm for authenticity and a postmodern ‘sense’ about authenticity’s artificiality” (Poecke 2017: 58). We will see this oscillation return in LaBeouf’s work.

But what is authenticity actually?

Lindholm makes the useful distinction between two overlapping forms of authenticity: historical (or genealogical) authenticity and, what I would call, ‘identity-authenticity’ (Lindholm 2018). Historical authenticity refers to the origin of something; that its roots can be verified. Think for example of an ‘authentic’ Rembrandt. On the other hand, ‘identity-authenticity’ – which as an ideal has grown with the rise of modernity – refers to constructing yourself; to creating your own set of values and meanings (Taylor 1992). In this reading, ‘being authentic’ means “to do your own thing” and “to find your own fulfillment” (Taylor 1992: 29). As both Charles Taylor and Charles Lindholm explain, this ideal of identity-authenticity is couched in terms of self-fulfillment and self-realization; it requires reflexive awareness about the ‘self’ in order to realize a potentiality that is properly your own.

These two forms overlap in the sense that we look for authenticity both in ourselves and in the outside world. We wish to consume products and experiences that we consider to be authentic and we ourselves want to be recognized and validated as truly authentic individuals: as someone who is true to his/her roots and whose life is a direct and immediate expression of his/her essence.

"If you seek authenticity for authenticity's sake, you are no longer authentic" - Sartre

But this modern ideal of authenticity is not merely about finding your true ‘self’ in isolation. It requires individuals to engage in society, to recognize that different interpretations of ‘the authentic life’ coexist and to “establish a relationship” between yourself and the Other “that will eventually result in cooperation, cohabitation and mutual respect” (Gaden & Dumitrica 2015: para. 28). Authenticity is therefore as much about ‘being for myself’, as it is about ‘being for others’ (Gaden & Dumitrica 2015: para. 4)

This all sounds wonderfully idealist but if we look at authenticity from a skeptical perspective, it all seems terribly naïve. After all, the moment you consciously decide to pursue authenticity, inauthenticity enters the stage. As Sartre already explained, authenticity is a self-defeating ideal: “if you seek authenticity for authenticity’s sake, you are no longer authentic” and “authenticity will unveil to us that we are condemned to create [ourselves] and that at the same time we have to be this creation to which we are condemned” (Sartre in Golomb 1995: 151).

In addition, pursuing authenticity in our modern-day society is not about respecting and helping the other in finding their authenticity: it is about consuming others who are deemed authentic in order to validate and consolidate one’s own authenticity using the power of social media. We can therefore say that we are witnessing a “shift from presenting the ‘real’ self to thinking about the ‘presentation of the real self’ in strategic terms” (Gaden & Dumitrica 2015: para. 19) and that the ‘idealist’ notion of authenticity has made way for a ‘strategic’ notion of authenticity.

So how do these Metamodern themes manifest themselves in LaBeouf’s performance art? In the following section I will give a reading of LaBeouf’s ironic way of apologizing and three of his artistic performances.

LaBeouf’s performance art

Plagiarizing apologies

Apologizing can be considered as an act of sincerity: you truly feel a sense of remorse about your actions and you express this remorse in the form of an apology in order to come clean to the person you have hurt. In the case of LaBeouf, we should also take the public nature of his apologies into account: his status as a celebrity forced him to not only come clean to the person in question, Daniel Clowes, but also to the rest of the world.

As we have seen, the way in which LaBeouf apologized was deliberately ironic. By posting inauthentic apologies, in the genealogical sense of which Lindholm (2008) speaks, he undermined the sincerity and authenticity that speaks from these apologies: his actions were not an expression of his essence or ‘self’.

In addition, LaBeouf can even be said to make a broader comment on the authenticity and sincerity of apologies in celebrity culture. Celebrities who are in the news because they have done something wrong – think for example of the recent #MeToo scandal – often apologize publicly and through the medium that has the widest reach: Twitter. By plagiarizing the apologies of other celebrities, he stands in this tradition but also criticizes it by bringing their generic nature to the fore by which he hints at their insincerity and inauthenticity.

#IAMSORRY (2014)

This piece, which shows striking resemblances to Marina Abramović’ The Artist is Present, featured LaBeouf sitting in a room with the already infamous ‘I AM NOT FAMOUS ANYMORE’-bag over his head. The participants were invited to pick an item (all which related to the movies in which LaBeouf has starred) before entering the room. Nothing happens when they have entered; they are merely confronted with a mute LaBeouf.

#IAMSORRY can be said to comment on the fact that authenticity is no longer pursued because we want to have sincere engagement with the outside world, but that it is pursued for strategic reasons.

There are several paradoxical elements to this performance. As Abigail Schwarz has noted, #IAMSORRY seems to be “swinging like a frenzied pendulum between opposing thematic elements” in true Metamodern fashion:

“LaBeouf wears a bag over his head that reads “I AM NOT FAMOUS ANYMORE,” yet people are lined up around the block just to see him wear it… his face is [originally] covered, but he is crying and seems to present an emotionally open front… you can do whatever you want within the exhibit, but there will be no record of you ever doing it… LaBeouf is sorry, and yet he again borrows from an artist uncredited… he is listening and reacting to what the audience has to say, and yet he wears earplugs…” (Schwarz 2014: para. 24)

In addition, the setting of #IAMSORRY invites people to have an affectionate, sincere and authentic experience with LaBeouf and some participants did. Yet a great deal of the participants did not answer this invitation. They were unable to see LaBeouf as a human being and instead ‘consumed’ him for the celebrity that he is. Many of the participants took selfies with LaBeouf in order to strategically enhance their authenticity online and some even removed the bag from his head to show their following that it was really LaBeouf! #IAMSORRY can therefore be said to comment on the fact that authenticity is no longer pursued because we want to have sincere engagement with the outside world, but that it is pursued for strategic reasons.

#IAMSORRY

All of this was made possible by the fact that LaBeouf, Rönkkö and Turner did not enforce any regulations: the participants were free to do whatever they wanted. One could thus say that the artists were naïve in expecting sincere and authentic experiences. Yet I would say that they consciously and knowingly drew out these kind of responses to highlight the gap that exists between the projection of a public persona and the realization that behind this projection (behind this mask or, in this case, bag) there is a real human being that wants to feel love, affect and be on the receiving end of empathy.

#IAMSORRY: table of props

Meditation for Narcissists (2014)

For this piece, LaBeouf jumped rope for an hour at his California villa. The recordings were streamed in real time to an art gallery. Visitors were invited to join him in this ‘meditative’ experience. To use LaBeouf’s words: “I hope that you take the ropes provided and join me on my quest to find my inner self”.

Informed by a postmodern skepticism, the ideal of authenticity is deliberately ridiculed in a sarcastic and ironic way for its self-absorbed and narcissist overtones.

Although the piece is called Meditation for Narcissists in plural, you could say that there was only one real narcissist: LaBeouf himself. He was the one who did all the ‘working’, observing and ‘finding’ whereas the observers were simply observing him instead of themselves. The fact that LaBeouf invited visitors to join him on his quest to find his “inner-self” whilst he was gazing at his own reflection highlights the narcissist elements involved in working out. As co-artist Luke Turner explained in an interview: “there is a thing about when you go to the gym, you do these things looking in a mirror. Is it a narcissistic thing or do you go into yourself? It’s a kind of split between narcissism and, it sounds cheesy, but the clichéd notion of finding yourself, some kind of enlightenment” (Swift 2014: para. 6).

Meditation for Narcissists

Here again we see the concept of authenticity emerging. The modern(ist) and ‘enlightened’ ideal of authenticity entails the exploration of yourself through reflexive awareness in order to achieve the goals of self-fulfillment and self-realization. Informed by a postmodern skepticism this ideal is deliberately ridiculed in a sarcastic and ironic way for its self-absorbed and narcissist overtones.

Yet in spite of this ridicule, the artists did seem to want to invite some form of engagement between LaBeouf and the participants by explicitly inviting them to join. Of course, there is no affective or sincere engagement taking place between them: the only thing that connects them is a digital live stream. One could say that this is Metamodern in the sense that the artists express a willingness to engage whereas they know that sincere engagement is difficult to establish in our digitally media saturated world. On the other hand, one could also say that they did achieve real engagement in the sense that visitors jumped rope together, making it into a communal thing. This seems to show that despite the narcissistic nature of ‘working out’, engagement is possible in this activity.

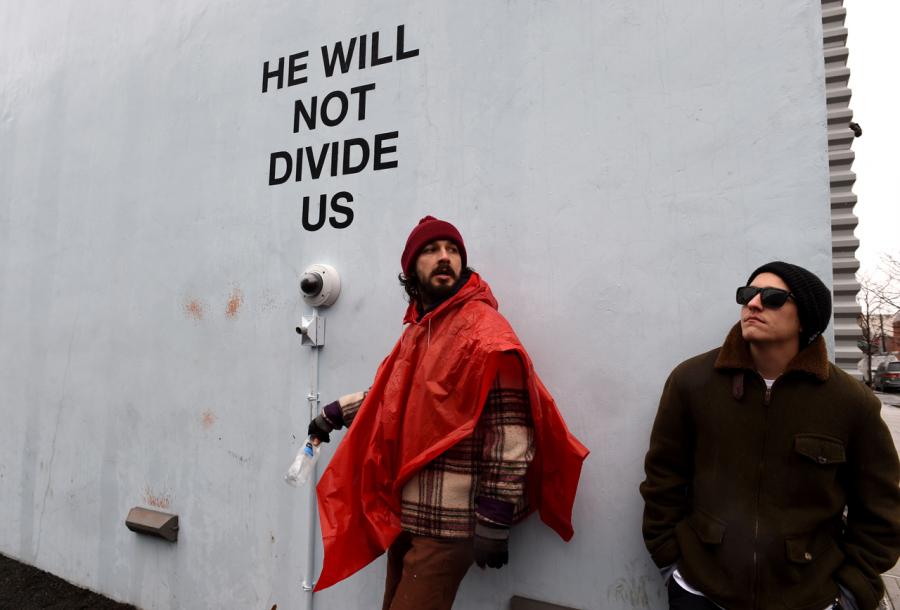

HEWILLNOTDIVIDE.US (2017)

On the day of Trump’s inauguration, January 20th 2017, a camera was mounted on a wall of the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens, New York. Above the camera, ‘HE WILL NOT DIVIDE US’ was written, a chant that passersby were encouraged to say, yell or sing into the camera for as long as they wished. The footage was streamed in real time to the website www.hewillnotdivide.us.

As we can read on the website above, “the mantra "HE WILL NOT DIVIDE US" acts as a show of resistance or insistence, opposition or optimism, guided by the spirit of each individual participant and the community”. Inspired by enthusiastic idealism, this piece wants to get a grand, socio-political, narrative across and invites passersby to become socio-politically engaged by interacting with the art work. This narrative, which obviously stands in sharp contrast to that of President Trump, preaches that having empathy and affect for those who are different from you makes the world a better place.

HEWILLNOTDIVIDE.US shows the exact opposite of what its title suggests: the project has become a lens through which we can witness how Trump has divided us.

LaBeouf, Rönkkö and Turner’s initial plan was to let this project run for the duration of Trump’s presidency. This turned out to be a terribly naïve aspiration. Contrary to the artists’ intent, HEWILLNOTDIVIDE.US became a meeting point for neo-nazi’s, white supremacists and 4Chan trollers who sarcastically disturbed the project. This eventually led to the arrest of LaBeouf who was involved in several verbal and physical altercations. Within a month, the project was abandoned by the museum because “the installation had become a flashpoint for violence and was disrupted from its original intent”. After a short-lived relocation of the project to Albuquerque in New Mexico, the live stream was taken down permanently. The live stream now only shows a HEWILLNOTDIVIDE.US-flag flying.

Shia LaBeouf at the installation of HEWILLNOTDIVIDE.US

This work can be considered Metamodern in the sense that it couples a naïve idealism to the inevitable realization that the artwork will do very little to fulfill its ideals. Although one could say that LaBeouf, Rönkkö and Turner managed to unite people for a cause that was larger than themselves; a great many people connected to one another by collectively and meditatively chanting, one cannot deny the fact that HEWILLNOTDIVIDE.US has shown the exact opposite of what its title suggests: the project has become a lens through which we can witness how he has divided us.

This artwork thus oscillates between the opposing themes that Vermeulen and van den Akker describe: “between a modern enthusiasm and a postmodern irony, between hope and melancholy, between naïveté and knowingness, empathy and apathy, unity and plurality, totality and fragmentation, purity and ambiguity” (Vermeulen & van den Akker 2010: 6).

Some of the thematic elements in LaBeouf’s performances can be related to Metamodernism, yet they could just as easily have been related to a fictional cultural philosophy called ‘paradox’, perhaps even better.

Concluding Reflections

In this essay I have attempted to give context to LaBeouf’s art- and public performances and to analyze the subversions of his own authenticity in the light of his affiliation to Metamodernism.

In all honesty, this was quite the struggle for the theoretical underpinnings of Metamodernism do not really allow for such an analysis. It seems to relate an abundance of several, disparate, sensibilities to one another under a header that presumably sums it all up. Just like the academics that coined such fashionable terms as ‘Automodernism’, ‘Digimodernism’ and ‘Hypermodernism’ before them, Vermeulen and van den Akker attempt to give context to the present by giving it a name. Yet this raises the question whether they are describing something that is already present, or whether they are simply creating a heuristic label for ‘artists’ to appropriate in order to give their work a cultural philosophical backdrop?

In my opinion, LaBeouf is a prime example of someone who has appropriated the term with this strategic motive in mind. Sure, as I have tried to show in my analysis, some of the thematic elements in LaBeouf’s performances can be related to Metamodernism, yet they could just as easily have been related to a fictional cultural philosophy called ‘paradox’, perhaps even better. It thus seems to me as if LaBeouf has appropriated the label of Metamodernism for strategic reasons rather than the idealist reasons of which Vermeulen and van den Akker speak.

LaBeouf appears to be ‘spinning’ his out of control behavior and his fall from grace in Hollywood into an artistic performance in order to control the damage that he has already done to his credibility. This makes me doubt the authenticity and sincerity of LaBeouf’s affiliation to Metamodernism. I see myself strengthened in this doubt by the fact that LaBeouf has been adding several arrests for drunken behavior to his name over the past couple of years. The latest one forced him to make public apologies on Twitter after he had racially slurred a black police officer. This time, due to the nature of his offense, LaBeouf could not strategically escape into the ‘postmodern’ irony and sarcasm of Metamodernism, but was forced to be truly authentic and sincere in his apology. Unfortunately for him, he has lost most of his credibility in that department.

As such, I have not found the answer to the question that sparked my initial attention in LaBeouf. ‘What the hell is going on with Shia LaBeouf’: I could not quite say.

References

Coster, R. (2013, December 16). Watch: Shia LaBeouf Takes on Online Film Critics in His New Short ‘Howard Cantour.com’. Retrieved from http://www.indiewire.com/2013/12/watch-shia-labeouf-takes-on-online-film-critics-in-his-new-short-howard-cantour-com-32123/.

Gaden, G. & Dumitrica, D. (2014). The ‘real deal’: Strategic authenticity, politics and social media. First Monday, 20(1). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v20i1.4985.

Golomb, J. (1995). In Search of Authenticity: From Kierkegaard to Camus. London, New York: Routledge.

Lindholm, Charles (2008). Culture and Authenticity. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Poecke, N. (2017). Authenticity Revisited: the production, distribution, and consumption of independent folk music in the Netherlands (1993-present). Doctoral dissertation: Erasmus University Rotterdam. Retrieved from: https://repub.eur.nl/pub/102670/Authenticity-Revisited-dissertation-Niels-van-Poecke-Final-version-.pdf.

Schwarz, A. (2014). On LaBeouf, Rönkkö & Turner’s Metamodern Performance Art. Retrieved from http://www.metamodernism.com/2014/04/08/on-shia-labeoufs-metamodern-performance-art/.

Swift, T. (2014). An interview with Luke Turner & Nastja Säde Rönkkö. Retrieved from http://www.aqnb.com/2014/05/19/an-interview-with-luke-turner-nastja-sade-ronkko/.

Taylor, C. (1992). The Ethics of Authenticity. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Vermeulen, T. & Van den Akker, R. (2010). Notes on Metamodernism. Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, 2(1).

Vermeulen, T. & Van den Akker, R. (2013, May 24). A New Dawn. Talk presented at Studium Generale Artez, Enschede. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9WPYFvB2DIc&t=1s.

Zakarin, J. (2013, December 16). Shia LaBeouf Apologizes After Plagiarizing Artist Daniel Clowes For His New Short Film. Retrieved from https://www.buzzfeed.com/jordanzakarin/shia-labeouf-rip-off-daniel-clowes-howard-cantour?utm_term=.nwRPdqGK6#.naRYx7b95.