Social media and why we're all full of shit

© Netflix

© NetflixFigure 1. American Vandal season 2 villain Grayson Wentz

Figure 1. American Vandal season 2 villain Grayson Wentz

This paper seeks to explore Instagram culture and how it shapes young minds. The inspiration for this piece comes from the second season of the Emmy-nominated mockumentary American Vandal. This mockumentary has been touted as the first TV show to fully understand how young people use social media (Vice, 2019).

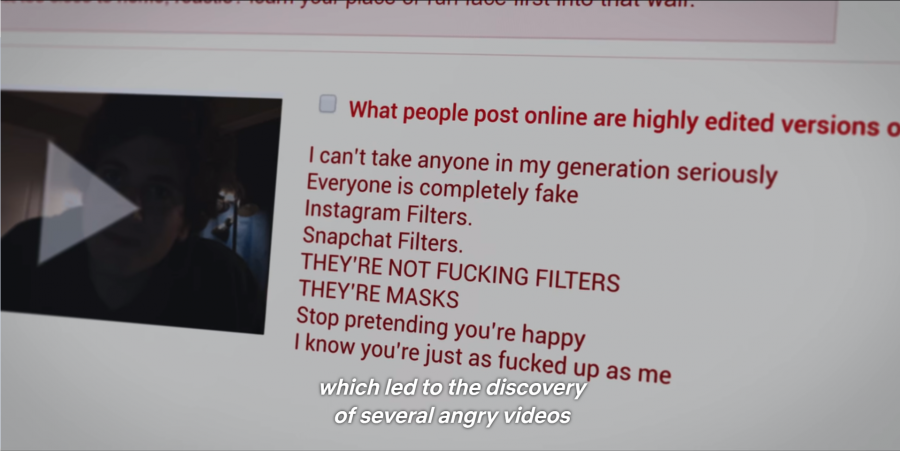

“You’re all full of shit”, Grayson Wentz (18) declared in an eerie self-taped recording in his dimly lit bedroom. He, an expelled student of St. Bernardine Catholic High school, aired out his frustrations regarding a generation that he perceives as socially inept. A generation that prides itself for illusions and fakery, a generation blinded by the game of social media. His generation. This and Wentz's other videos came prior to him seeking and exacting his vengeance on multiple classmates and members of staff at his high school. Wentz can be seen as a product of toxic techno-cultures that exist primarily on Reddit and 4chan, where these communities flourish in environments with minimal to no accountability as well as anonymity (Massanari, 2015). This troubled teen knew how to inflict damage in a digitized and interconnected cyberworld: his methods included cyberbullying, identity theft, catfishing, blackmailing and finally revenge porn.

Wentz is a villain in American Vandal, but like many great villains in cinema, he is believable, and his initial grudge against his "brainwashed" classmates makes sense. He is frustrated by the doctrines his classmates follow: doctrines dictating that likes and views equal popularity and popularity in turn equals a higher social standing. He despises their eagerness to become slaves to this "popularity principle" (van Dijck, 2013). He operates through Instagram in particular, and wants to expose his classmates for who they really are: classmates that are "full of shit". When glancing at the shocking acts that Grayson Wentz orchestrated, it seems vital to ponder why we, as consumers of social media, feel the urge to live almost second lives online, and what the consequences of that are.

How did we get here?

It is important to paint the full image as to how we got here. A short history lesson is key to explaining the phenomenon we nowadays know as social media.

Since the inception of the worldwide web in the early 1990s, the internet has contributed to setting trends and reshaping our culture and how we interact with each other. In its early stages, the internet was to a great degree a place of one-way communication: blogs or news sources communicated to users by simply uploading their data with no visitor-generated content in response, such as comments.

As necessity would have it, platforms emerged to facilitate the needs of users. The term "Web 2.0" was coined to describe this new era of visitor-generated content. It led the way for the social media platforms we know today to take ground. Social media allowed users to communicate back to the platform while also allowing communication between other users, in what is known as two-way communication (van Dijck, 2013).

With social media platforms like Facebook taking root, the methods through which people socialized online shifted from instant messaging software like MSN to browser-based communication through Facebook Messenger. Entire internet subcultures emerged on sites like Reddit and 4chan. The youth began to express themselves with new mediums such as memes, vines and wacky YouTube videos. In essence, Facebook and its kind became mediators, shaping the performance of social acts rather than only facilitating them (van Dijck, 2013).

As an instance of this mediation, in its prime, Facebook, like many other platforms, made connectivity quantifiable. You could see how connected someone was through their number of friends, or followers. This introduced the popularity principle, where your numbers define your sociability and status (van Dijck, 2013).

Facebook came to be the dominant platform in the 2000s as it cannibalized other similar competitors like Bebo, Hi5, and Myspace. A new member has since entered the fray, one with a different model than Facebook. Something innovative and unique: Instagram.

Dawn of Instagram

Instagram was launched in October 2010. It was an app simply for users to upload photos and videos on. It had the added functionalities of adding hashtags, applying filters to pictures, and liking posts. Its charm is in the posts. It gives off a vibe of always being on the go and inviting friends and strangers to see a snippet of one's everyday life. It’s such a unique idea that Facebook purchased it for 1 billion dollars just two years later (Marwick, 2015).

Instagram propelled and still propels the popularity principle, to the point where followers can now be bought online.

Instagram gives its users the feeling that they are on a first-name basis with celebrities. It allows for famous people to provide snapshots of their lives and a sense of easy access to their fans. In a parasocial relationship, fans respond to media figures as if they were personal acquaintances (Giles, 2002).

Instagram propelled and still propels the popularity principle, to the point where followers can now be bought online (Baggs, 2019). One can argue that the monetization of the principle led to this outcome. However, this comes as no surprise, as this is a prevalent trend with many other monetized social media platforms too (Masek-Kelly, 2019).

The worrying issue, however, isn’t so much Instagram’s monetization of popularity or users buying follower bots. The issue has to do with how we use Instagram, why we use it, and how it (as a mediator) shapes us in the offline world.

In 2019, the British Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) and the Young Health Movement (YHM) published a report examining the positive and negative effects of social media on young people’s health. Instagram came out at the bottom, being the most detrimental to the mental health of teenagers and young adults.

The findings of the report make it clear that there is a marked increase in mental health issues in the age group that consumes social media the most, the 16-25 age group. The paper reported a 70% increase in anxiety over the past 25 years. It is one of the three prevailing negative side effects social media has on teenagers, two other major issues being cyberbullying and "FoMO" or Fear of Missing Out.

American Vandal and teen Instagram use

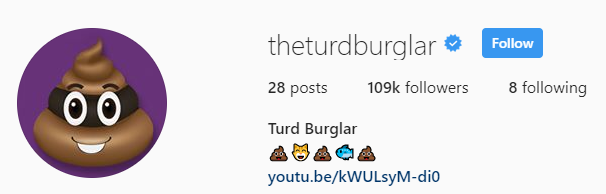

Figure 2. @theturdburglar's Instagram account

The secibd season of American Vandal is about two young journalists investigating a villain that has been terrorizing the St. Bernardine Catholic High school for weeks. After 8 episodes of extensive investigation, a student named Grayson Wentz is revealed to be the primary culprit.

Wentz was expelled for using school computers to insult fellow students online, doing so through their own accounts if they had failed to log off. He sees his expulsion as unfair and creates the online persona "the Turdburglar" on Instagram.

The first incident that Wentz is accused of occurs in the school cafeteria where students that have drunk lemonade begin to uncontrollably defecate. It is revealed that someone put a laxative called maltitol into the lemonade container. The container is left with a @theturdburlgar business card. The culprit wants to be noticed. This incident is dubbed "The Brownout".

WARNING: THE IMAGES IN THIS VIDEO MAY BE DISTRESSING TO SOME

In further incidents, a piñata is struck by a student during a school event, and at the second strike it erupts into a torrent of feces. That day a picture of the piñata is uploaded to the Turdburglar Instagram account, once again with his business card.

Later, at a pep rally, a t-shirt cannon is used, and as the shirts are fired so is a cloud of dried feces in powdered form. Once again a picture of the cannon is posted online along with the calling card of the Turdburglar.

The high school janitor ("Hot Janitor") alerts the investigators of a fourth fecal crime involving chocolate-covered cat feces in an advent calendar, an advent calendar that was present on the Turdburglar's Instagram account.

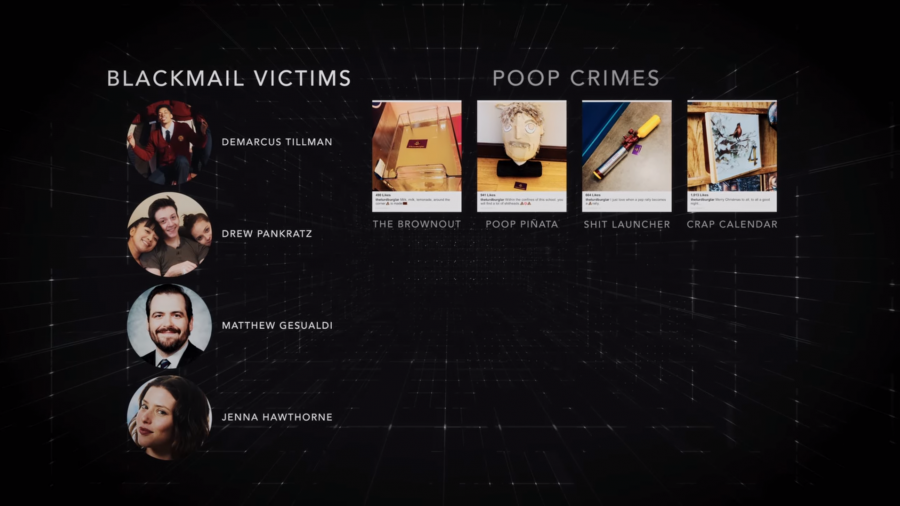

The final crime was less of a fecal crime and more of a data dump, similar to that of the fappening. A link containing a vast amount of sensitive data was made available to all students and faculty in the Turdburglar’s Instagram bio. This compromising data included leaked nudes of students and a member of the staff, as well as a student performing a sex act. Students view this sensitive data without much regard for its ethical aspects, similar to how Massanari (2015) describes the images in the fappening and how they were disseminated by Reddit users with glee. It is revealed that Wentz catfished classmates to reveal sensitive data on them. The data is used to blackmail students into commiting his fecal crimes.

Figure 3. Blackmail victims and their crimes

Social media's negative effects in relation to the students

7 in 10 young people (ages 16-25) have experienced cyberbullying in the UK, and recent statistics show that that young people are more likely to be bullied on Facebook than on any other form of social media (RSPH, 2017). This statistic comes to life in American Vandal, especially through the story of the student who sees himself as a social pariah, Kevin McClain. As mentioned, the three main detrimental factors that affect teens on social media are anxiety, cyberbullying, and FoMO. So, do these negative trends play out in St. Bernardine? This section analyzes the cases of students Kevin McClain and Jenna Hawthorn.

Kevin McClain

Figure 4. Kevin McClain during an interview

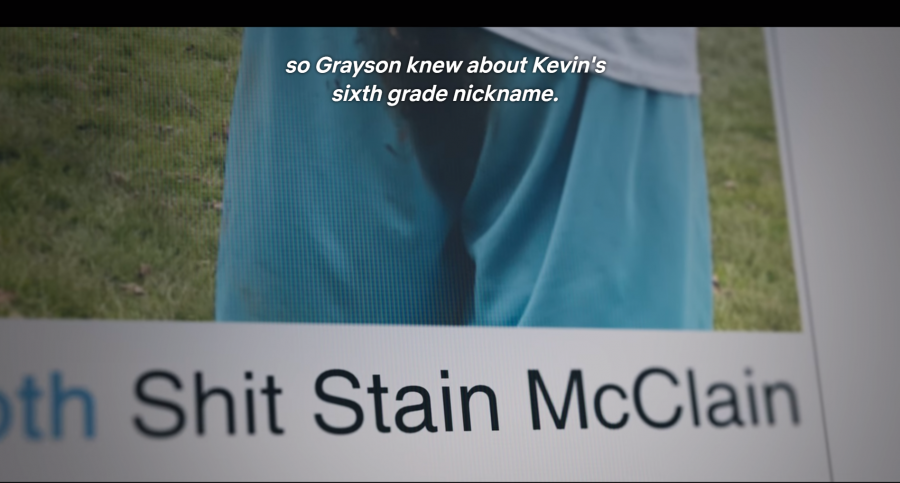

Kevin McClain is the initial suspect for the "Brownout". Suspicion for him stems from his history of being on the recieving end of cyberbullying from a young age. In the sixth grade, he once had a bathroom accident during gym class which sadly earned him the title of "shit stain McClain". A picture emerged of this accident and was posted on Facebook. It was shared amongst classmates, much to Kevin's displeasure. Upon being approached by a suspiciously friendly girl on Instagram (Wentz catfishing him), Kevin is convinced to carry out the "Brownout" crime so he can watch his classmates go through the same shame he suffered.

Figure 5. The 'Shit Stain McClain' post used to cyberbully Kevin

Jenna Hawthorne

Figure 6. Jenna Hawthorne's image pinned as a suspect's

Jenna Hawthorne is the perfect example of the tactics that young people undertake to appear more "polished" on social media. Her Instagram page is highly pruned and staged, with each post aiming to make viewers envious of her lifestyle. This is done to sell the idea to her peers that she is living a fun, lavish, and spontaneous life.

Hawthorne partakes in parasocial activity as she insinuates her close relationship with supermodel Kendall Jenner through an Instagram post (Marwick, 2015). Her classmates later reveal that her picture with Jenner was from a public photo op that Jenna had waited in line for hours to attend. The crime here was that the photo she had uploaded was cropped to appear as if she maintained a personal friendship with the celebrity. This sort of behavior amongst young people is driven by a fear that they are not enough and thus have to appear as someone bigger or better on social media (RSPH, 2017). Jenna's posts feed into the idea that authenticity doesn't coincide with the doctrine of the popularity principle. Her post is knowingly manufactured to sell an idea of exclusivity with a superstar in exchange for an increase in possible likes and shares on her Instagram page. In essence, a post with a superstar is top dollar in the attention economy.

Figure 7. Jenna's infamous Kendall Jenna Instagram post versus the reality

At some point, Jenna Hawthorne is contacted by a fake Instagram account named Brookwheeler99, who is actually Grayson Wentz catfishing her. He takes advantage of her anxiety from having to keep up her ever-evolving good appearances on Instagram. They form a bond stemming from Jenna's need for a confidant and in order to share sexually charged photos with one another. Wentz takes the opportunity to use the photos as leverage and forces her to partake in one of his fecal crimes. On the day of "The Dump", her naked images are part of the files that are sent to the entirety of the school.

Figure 8. Grayson Wentz's video manifesto posted to 4Chan

Conclusion

Grayson Wentz carried out these "poop crimes" to send a message, to literally expose people for the fact that they wore masks online and presented themselves on Instagram not as they truly were. He labelled them as "full of shit", which in itself is an exaggeration that drove his sick crusade for vengeance. There is truth in Wentz’s gripe with his classmates: we do present different versions of ourselves online. But are we all full of shit?

What Grayson Wentz failed to notice is that the masks that we and his classmates wear are actually a single piece of a full set of armor.

Millennials and Gen Z individuals have been the beta testers for social media; the lab rats, if you will. We’re only beginning to research the long-term effects of constant exposure online and the pressure of the need to display a specific lifestyle on social media. We don’t fully know the repercussions of this lifestyle, but what we do know is that it puts an increasing amount of stress and pressure on young individuals to force unrealistic standards on themselves and others.

However, what Grayson Wentz failed to notice is that the masks that we and his classmates wear are actually a single piece of a full set of armor. The internet can be a hostile and unforgiving environment. This armor helps us build self-assurance. It allows us to explore who we really want to be and, in turn, teaches us to be comfortable with who we are. This shield is imperative, especially in a time where a constant barrage of marketing is forced on teens, scaring them into complying to a social norm or risk being labeled a pariah or an outsider. These online identities offer young people protection, and allow them to shed them in time, upon discovering their own selves. This is an increasingly daunting task in a never-ending sea of constant curation of all facets of social life. As the final sequence of American Vandal so rightly states, we’re witnessing a generation that has to live twice. So no, we're not full of shit, we're just playing the game that is social media.

References

'American Vandal' Is the Only Show That Knows How Teens Use Social Media. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/qvabjb/american-vandal-is-the-only-sh...

Baggs, M. (2019). Why fake followers are bad news for real fans. BBC. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-48952123

Dijck, J. van (2013). The culture of connectivity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Giles, David C. (2002). Parasocial Interaction: A Review of the Literature and a Model for Future Research. Media Psychology, 4(3), 279–305.

How Facebook Beat MySpace. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/adamhartung/2011/01/14/why-facebook-beat-my...

Marwick, A. (2015). Instafame: Luxury Selfies in the Attention Economy. Public Culture, 27(1 (75)), 137-160. doi: 10.1215/08992363-2798379

Masek-Kelly, E. (2019). 3 Ways To Monetize Social Media That Actually Work. Social Media Today. Retrieved from https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/3-ways-to-monetize-social-media-th...

Massanari, A. (2017). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

RSPH (2019). Instagram ranked worst for young people’s mental health. Retrieved from https://www.rsph.org.uk/about-us/news/instagram-ranked-worst-for-young-p...

Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/