What did the Jheronimus Bosch Year teach us for upcoming cultural theme years?

Importance of a Cultural Theme Year

This essay critically analyses the Jheronimus Bosch cultural theme year, hosted in the relatively small Dutch city of Den Bosch last year (2016). How did this event, and the exhibition with the works of Bosch, come into being? Who were the major stakeholders and partners? Does investing in such a cultural event pay off; what was its social and economic impact? And what do upcoming cultural theme years need to take into consideration when hosting such an event? First and foremost, who was Jheronimus (Jeroen) Bosch and what cultural heritage did he leave behind?

The Devil’s Painter

In 1450 Jheronimus (Jeroen) Bosch was born in the Dutch city of ‘s Hertogenbosch. He grew up as Jheronimus van Aken, but signed his works with ‘Bosch’, after the city in which he was born and where his father, grandfather and other family members also worked as painters. His works consist of eccentric imagery and detailed landscapes, often with a religious or narrative concept that relates to the afterlife. Thirty years after his death, Bosch was described as ‘’the devil’s painter’’, due to his satirical and often macabre portrayals of hell. For centuries after his passing in 1516 he kept, and still keeps, inspiring artists, academics and others, who face his fascinating works of art. Only twenty five panels (paintings) and twenty drawings of his hand are known to have survived the test of time at this point. During the last five centuries, the legacy Bosch left behind has become part of the collections of some of the great international museums, like the Louvre in Paris, the Metropolitan in New York and the Prado in Madrid. None are still present in the city of his birth (Kennedy, 2015).

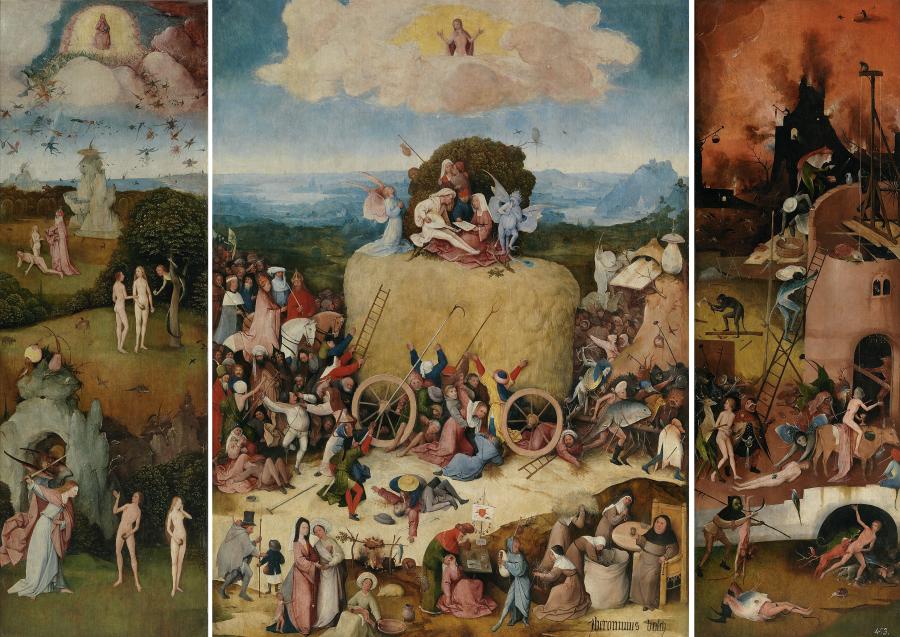

Jheronimus Bosch - the Hay Wain - 1510-1516. One of Bosch' most iconic paintings.

Back in 2001 however, when the Dutch Museum Boijmans van Beuningen (in Rotterdam) hosted an exhibition with works of Bosch, the mayor of ‘s Hertogenbosch (or, Den Bosch), Ton Rombouts, decided this had to change. He thought his city should also come up with an event related to the namesake of his city. This should contribute to a culturally, socially and economically stronger city. His ultimate goal was to bring back all of Bosch’s remaining forty five works of art. This should be achieved in 2016, exactly five hundred years after the death of the painter. He was inspired by a similar project hosted in Den Bosch in 1967. Back then, this small Dutch city – that at the time did not have any experience with hosting an exhibition, no proper building nor artworks to trade – brought back several of Bosch’s masterpieces. The exhibition became a major success with over 300.000 visitors. Currently, Den Bosch hosts the (professionally led) Noordbrabants Museum, that opened its doors in 1983. In 2008, Rombouts, together with Charles de Mooij, director of the Noordbrabants Museum, decided to start the seemingly impossible project of bringing Bosch back to Den Bosch. From the first moment onwards, the mayor decided to brand his city (abroad) as the city of the famous Dutch painter (Schoone, 2015).

Visions of a Genius

First, De Mooij had his doubts about the mayor’s ambitious plans, because the practicalities surrounding such a project were in the hands of himself and his museum. While it is common practice for museums to loan works of art, the small Noordbrabants museum had one significant problem: they could not offer their colleague museums any paintings in return. In order to get a chance to obtain these works of art the Bosch Research & Conservation Project was brought into existence. In return for the panels and drawings, the museum offered a model that other small museums also use in order to mount major exhibitions: knowledge. With the (financial) help of the municipality, a big international research project about the life and works of the Dutch painter was set up. Next, the Getty Foundation, that (financially) supports projects related to the preservation and understanding of art, decided to participate in the Bosch project. This meant that the Noordbrabants Museum could offer museums like the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the Louvre in Paris what they have learned throughout the project about the specific painting they loan (Kennedy, 2015).

The Guardian stated that the Bosch exhibition is ‘’one of the most important exhibitions of our century’’.

During these five years of research, the Bosch Project’s most significant finding was the discovery of a work by Bosch that, for years, lay in storage at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. Eventually the small museum from Den Bosch acquired seventeen of the twenty five panels and nineteen of the twenty drawings. A few panels were in too poor a condition to travel. Also, Bosch’ most significant and most famous work, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1510), was never going to leave the Prado in Madrid, because this is the museum’s showpiece (Kennedy, 2015). The Dutch museum solved this omission by creating an interactive adventure, in which people could ‘’wander through the painting’’, or follow an online audio-visual tour ‘in’ the panel. On February 12th 2016, ‘Jheronimus Bosch - Visions of genius’ opened in the Noordbrabants Museum. The exhibition got a laudatory reception. The Guardian stated that this exposition is ‘’one of the most important exhibitions of our century’’, de Volkskrant described it as ‘’mysterious, scintillating and extremely fascinating’’ and New Republic claimed that it was ‘’a feast for the eye’’.

Dutch King Willem Alexander opened the Jeroen Bosch Year, and subsequently visited the exhibition 'Visions of Genius''.

Back in 2009, the municipality decided to establish a multiannual program, in addition to the exhibition, in order to keep Bosch related to the city of Den Bosch for a lasting period. The foundation Jheronimus Bosch 500 was brought into existence. This foundation was responsible for the elaboration and creation of the multiannual programme: a big cultural manifestation (which includes the exhibition), under the guidance of superintendent Ad ’s Gravesande, a business director, a program manager and seven staff members. This event reached its climax in 2016, which was officially named the ‘Jheronimus Bosch year’ (Bosch500.nl, n.d.). The opening of the year and of the exhibition, by King Willem Alexander, was broadcasted live on Dutch national television.

Over ninety events related to Bosch were set up in (the surroundings of) the city: several exhibitions, theatre and dance shows, concerts, festivals, lectures, a Jheronimus Bosch circus and several city events. The Bosch Grand Tour, for example, was a project of seven provincial museums that all hosted an exhibition about, or related to, the famous Dutch painter. Then there was The Bosch Experience: in collaboration with theme park the Efteling, Bosch 500 set up a discovery route that followed the tracks of Bosch through the city. Visitors could go on a ‘heaven and hell boat trip’, climb to the roof of the old cathedral or watch a light show (‘Bosch by night’). Moreover, Bosch’ cultural heritage got promoted via a widespread educational project for children. The Bosch year ended with a big final manifestation, where the ‘Bosch beast’ was revealed: an owl that was nine meters high, which is an animal that often appears in Bosch’ works.

Stakeholders and Sponsors

An event like the Bosch Year is only possible when the persons who take the initiative, the mayor, the museum and the foundation, get several partners and sponsors involved to make such a project into a success. In the case of the Jheronimus Bosch 500 project, a strategic collaboration project led to a large number of generous partners. The foundation, as described in the previous section, was the major stakeholder. They set up the cultural program and attracted sponsors. On their website, the foundation differentiates between seven types of partners, who contributed twenty eight million Euros to the project together:

- Subsidy providers: the municipality of ‘s Hertogenbosch (eight million Euros), the province of Noord-Brabant and the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (both five million Euros). The partners below contributed a combined amount of approximately ten million Euros;

- Founding partners: energy company Essent and the Bank Giro Lottery;

- One major sponsor for the exhibition: the Dutch Rabobank;

- Seven sponsors for the entire project: animal feeding company De Heus, airline company KLM, the Dutch ABN AMRO bank, postal company PostNL, the building and culture fund, construction building service Heijmans and DMG kitchens;

- Fourteen business partners (including brands like Heineken and Ricoh)

- Five patrons: each for another part of the Bosch Year (two for the exhibition, one for the education project, one for the Research and Conservation Project and one for a research project at the University of Nijmegen);

- One Maecenas and several benefactors;

- Media partner AVRO TROS;

- Corporation partner BKKC (Brabants Knowledge Centre for Art and Culture)

All these partners subsidised, donated and invested, besides their knowledge and other practical matters, especially in relation to the final two stakeholders, a financial contribution in return for exposure and goodwill. From the twenty eight million Euros, twenty five percent (7 million Euros) were secured due to box office sales (tickets for the exhibition and the events). Twelve million was spent on the exhibition, the Research and Conservation Project and the restoration of several panels. The remaining sixteen million Euros were invested in the multiannual program that lasted from 2010 till 2016 (Bosch500.nl, n.d.).

Several partners together contributed twenty eight million Euros to the Jeroen Bosch Year.

When briefly comparing this to the current Mondrian Year in The Hague (2017), it appears that they invest far less money in their project. This is mainly because the Haags Gemeentemuseum already has three hundred works of the abstract painter in its collection, on which they can build their exhibition. What's more, nine cultural initiatives are being organized with a budget of 150.000 Euros (subsidized by the municipality of the Hague), and the works of Mondrian were brought into the public space via posters and big pictures. Their goals also include attracting tourists for the city, and to create a bigger cultural awareness among its (Dutch) visitors.

Economic Impact

The investments mentioned above, especially the investment by the municipality of Den Bosch, led to some criticism in the Dutch city. People called it ‘’too expensive’’, ‘’for the elite’’ and contemporary artist Ralph Posset made a public statement when he placed a big picture of himself over the statue of Bosch in the city centre. He disagreed with the fact that large amounts of money were spent on an artist who has been deceased for five centuries now. Instead, contemporary artists should get more attention and appreciation. Mayor Rombouts refuted this criticism by stating that people from Den Bosch ‘’are on the front row, […] but they have to be open for it.’’ Looking back on the event, it appears that the entire city profited financially from the Jeroen Bosch Year. The exhibition in the Noordbrabants Museum attracted 421.700 visitors in just three months, of which 105.000 (twenty five percent) were foreign tourists.

People eagerly waiting in line in front of the Noordbrabants Museum.

At the end of the year the museum expected to have welcomed around 510.000 people. In comparison, in 2015, 180.000 visitors came to the museum. ‘Jeroen Bosch – Visions of Genius’ was such a big success that the museum decided to extend its opening hours – at the end up to 124 hours a week (the tickets for the exhibition at night were also sold out in no time) – which earned them a number ten spot in the top ten exhibitions that were most visitied worldwide in 2016. To top it all, the Dutch museum won, as the first Dutch museum in history, a prestigious Global Fine Art Award in the category ‘Best Renaissance, Baroque, Old Masters, Dynasties – solo artist’.

The stakeholders rightly claimed that the exhibition was a big (financial) success. However, next to all the positive remarks regarding the content of the exhibition, there were also some negative reactions form visitors. As a result of the massive – and positive – media attention, people described the exhibition being ‘’unpleasantly busy’’, ‘’too crowded’’ (up to forty people standing in front of the (bigger) works) and ‘’too dark’’. The works of Bosch are very detailed and therefore it was, when observing from a distance, ‘’difficult to get a good impression’’. Subsequently this led to people who found it problematic to genuinely enjoy the works to the fullest extent (TripAdvisor.nl, 2016).

Finding a proper balance between the interests of the stakeholders and the community can be difficult and should be taken into serious consideration when hosting a blockbuster exhibition.

One could perhaps even state that the exhibition, to a certain extent, was spoiled by its own success. Finding a proper balance between the interests of the stakeholders (in this case, the museum who want to promote their exhibition and sell tickets, and the municipality, who want to promote tourism) and the community (the visitors, who expect a decent exhibition experience) can be difficult and should be taken into serious consideration when hosting such a blockbuster exhibition.

The first results from the entire Bosch Year show that the municipality of Den Bosch welcomed at least 1,3 million extra visitors in its city – which obviously led to more revenues for the hotel and catering industry, and the many restaurants and bars. Fifteen percent more people went on holiday in the province of Noord-Brabant, in comparison with an average year. The museums that were affiliated with the Bosch Grand Tour also saw an increase in visitors. Together these seven museums attracted about 400.000 guests for their thirteen exhibitions. What's more, over 415.000 people followed the footsteps of the Dutch painter by participating in the Bosch Experience Route. More visitors means more income. The national and international media attention generated a media value of approximately twenty million Euros: the biggest amount of money for a Dutch cultural event in history. It is already clear that the event finishes with a positive balance: the Bosch Year earned money for the Dutch municipality and for the province of Noord-Brabant. Superintendent Ad ’s Gravesande emphasizes this: ‘’the success of the Jheronimus Bosch 500 manifestation shows that investing in art and culture pays off’’ (Bosch500, 2016).

According to program manager Lian Duif, Den Bosch has earned approximately 150 million Euros due to all the people visiting the city. Next to the hotel and catering industry, items from the museum shop and the typical Den Bosch delicacy, the ‘Bossche Bol’, sold very well. This also applies to the 12.000 Jeroen Bosch napkins that were retailed, 30.000 litres of Jeroen Bosch beer that were served and over 100.000 Bosch postcards that were sold. One can state that the Bosch theme year was a big economic success.

Social and Cultural Impact

In addition to these economic benefits, an event like the Bosch Year also offers opportunities to create cultural awareness, to have a social impact and get the community involved with culture. The major stakeholder, the Bosch 500 foundation, made it one of their main goals to connect the project with the citizens of Den Bosch. Creating support under the inhabitants was of crucial significance for the foundation. They promoted participation in several ways. Citizens were, for example, able to send proposals of (cultural) events they would like to see or do in 2016. Out of these proposals the most interesting events were selected by the Bosch 500 Panel. In this panel, introduced in 2013, citizens from Den Bosch (locals), all with different socio-cultural and economic backgrounds,who were aware of the goings on in their city, helped develop the Bosch 500 program. Moreover, the Bosch 500 café was introduced. This café had the goal to keep citizens from Den Bosch involved and up to date with the progress of the manifestation. The foundation also sought collaboration with several local organizations, for example musicians and fanfares from the city and neighbouring municipalities, to participate in the festivities (Jeroen Bosch annual report, 2015, p. 10).

Mayor Rombouts also emphasizes the social profit of such a project. All the activities in and around the city – which led to hundreds of volunteers and hosts, and to thousands of people who have found inspiration among each other and in the works of the Dutch painter – contributed to the successful 2016 year. There were over eight hundred volunteers, who all received a medal of appreciation from the municipality of Den Bosch for all the work they had done. Another significant example of the social cohesion created by the project is the fact that the owl of nine meters high, that was revealed during the final day of the Bosch Year, was created by 350 inhabitants of Den Bosch, who all worked in shifts to finish this work of art in time.

The Bosch Year ended with the revealing of the ‘Bosch beast’: a nine meters high owl, an animal that often appears in Bosch’ works.

The Jeroen Bosch Year also had an unmistakable cultural impact. Jheronimus Bosch has become part of the city and society of Den Bosch. In 2016, according to Ad ’s Gravesande, a lot of people who were unfamiliar with the Dutch painter and his importance for his city, were successfully introduced to his work – either in the museum or in the public space. This mostly concerns Dutch people, especially those who live in the municipality of Den Bosch, and who would not consider themselves regular museum visitors. The Noordbrabants Museum got the opportunity to extend their network and to form new partnerships, which in the (near) future could lead to even more exhibitions that appeal to a wider audience than the ‘regular’ museum visitor. Given the fact that the Jeroen Bosch Year had such a big local, national and international impact in 2016, the city of Den Bosch was awarded with the Dutch jury and public Network City Marketing award.

The Jeroen Bosch Year had an unmistakable cultural impact. Jheronimus Bosch has become part of the city and society of Den Bosch.

However, as with the exhibition, there are also tensions between the stakeholders and the community in the case of the cultural program organized in the public space. For the stakeholders, the Bosch 500 foundation, having (a lot of) visitors in one’s city is obviously very attractive and interesting from a financial perspective, just as getting locals to participate in a cultural program. At what point become the interests of tourists more important than those of the inhabitants of a city though? According to professor of urban economy and tourism, Jan van der Borg (University of Venice), maintaining a policy based on (mass) tourism in the public space can lead to ‘’Disneyfication’’. For local inhabitants it can feel like they live in some sort of amusement park. It no longer feels like ‘their’ city, in which they work and interact with each other, because one’s hometown has become a kind of open air museum, in which its inhabitants have become one of many museum pieces. Think of cities like Venice, Barcelona and most recently Amsterdam, where mass tourism that gets out of hand, leads to a vanishing social cohesion among its citizens (Kruywijk, 2016). The city of Nantes, on the contrary, is a good example of how art in the public space can lead to a sustainable city life.

Sustainable Future

Finally, for a sustainable future it isimportant that, when having invested tens of millions, the cultural program continues, to a certain degree, after the theme year has passed. But how to keep people, on a local and (inter)national level involved with culture in your city, with far less money? The city of Den Bosch is working on a Bosch legacy program, ‘’that builds on the pride for Bosch’’. An example of how they want to achieve this is the organization of three periodical and public events related to the deceased artist, that are hosted in cooperation between (local) artists and local organizations and by bringing works inspired by Bosch’s paintings, in the public space (SpotDenBosch, 2016). What's more, there are plans for organizing future exhibitions (in the Noordbrabants Museum), with just one or two works of Bosch – built on the partnerships of the successful 2016 exposition. Furthermore, his works of art can also still be used for educational programs, for example by using interactive games.

During the Jeroen Bosch Year, Bosch' works were brought into the public space.

Conclusion and Recommendations

So, what did the Jheronimus Bosch Year teach us for upcoming cultural theme years? It is only fair to say that the Bosch Year – the cultural event in the public space and the exhibition – was successful. The stakeholders, in this case the mayor, the museum director and the Bosch 500 foundation, represented and carried through their policy with a clear vision and conviction of the importance of culturel in general, and cultural heritage more specifically, for society. This appeared to be the foundation on which partners and sponsors were likely to participate.

The social and economic impact were high. By taking Bosch' paintings as a starting point, a lot of people came in touch with his cultural heritage in the city of Den Bosch and at the exhibition in the Noordbrabants Museum. Local inhabitants of the city were included in the event as much as possible in order to improve social cohesion and cultural participation. Moreover, investing in culture also pays off from a financial perspective. Culture can make money for a city, municipality and province, and is thus beneficial for the entire country.

Investing in culture pays off. Culture can make money for a city, municipality and province, and is thus beneficial for the entire country.

However, in order to keep a cultural theme year sustainable in the future, there are some things that need to be taken into consideration. The main question one should ask is: is your city, and if relevant, your museum, ready to deal with the success that can come with organizing such an event? It is interesting to only look at the numbers, which represent the success of such an event, but besides these numbers of visitors and the money that is being made, stakeholders are on a thin line when trying to find a proper balance between their own interests and those of the community. When one does decide to host such an event, these suggestions should be taken into consideration:

- The museum experience: find a proper balance between the interests of the stakeholders (the museum who want to promote their exhibition and sell tickets) and the community (the visitors, who expect a decent exhibition experience). This can be difficult and should be taken into serious consideration when hosting such a blockbuster exhibition;

- Do not overdo it: it is key to find a proper balance between, on the one hand, involving people with culture and attracting tourists, and on the other hand, taking inhabitants' concerns into account, in order to keep your city an actual city in which people work and live. In this regard, one can wonder whether the ninety(!) events that the Jheronimus Bosch 500 foundation organized over the course of 2016, perhaps was too much of a good thing. Especially because ‘Visions of Genius’ already attracted a lot of (international) tourists to the relatively small city of Den Bosch;

- Maintaining the legacy: when investing (a lot of) money in a cultural event, it is recommendable to keep it visible after the event is over. Thus, making use of people’s increased interests in (local) culture. However, one should be aware of not carrying through a policy that is too one sided. In this case, keeping Bosch connected to the city is recommendable, but Den Bosch is also more than just Jheronimus Bosch.

References

Agence France-Presse. (2016, February 1). Art researchers uncover 'lost' Hieronymus Bosch – and sausage link. the Guardian.

ANP. (2016, December 10). Den Bosch is (bijna) uitgeBoscht. Nederlands Dagblad.

ANP. (2017, April 9). Ruim neventig evenementen in Jeroen Bosch-jaar.

Bartol, R. (2016, January 3). Standbeeld Jeroen Bosch op Bossche Markt doelwit van protestactie tegen Jeroen Boschjaar.

Bijdragers & Beoordelaars. (n.d.). Beoordeling Noordbrabants Museum [Forum post].

BNR Nieuwsradio. (2016, December 19). Mondriaanjaar moet buitenlandse toeristen naar Den Haag lokken [Video file].

Brabants Dagblad. (2016, December 11). Waarderingspenning voor achthonderd Jeroen Bosch-vrijwilligers.

Dunmall, G. (n.d.). The resurrection of Nantes: how free public art brought the city back to life. the Guardian.

Handler Spitz, E. (2016, March 25). The Impious Delights of Hieronymus Bosch.

Het Noordbrabants Museum. (2017, February 12). Het Noordbrabants Museum wint Global Fine Art Award 2016.

Van Huut, T. (2016, May 8). ’s Nachts nog één keertje dringen voor de schilderijen van Bosch. NRC Handelsblad.

Jheronimus Bosch 500. (n.d.). De Tuin der lusten van Jheronimus Bosch.

Jheronimus Bosch 500. (n.d.). Stichting Jheronimus Bosch 500.

Jheronimus Bosch 500. (n.d.). Ontdekkingsroute.

Jheronimus Bosch 500. (n.d.). Onze Partners.

Jheronimus Bosch 500. (n.d.). Eerste resultaten Jheronimus Bosch 500 bekend.

Jones, J. (2016, February 11). Hieronymus Bosch review – a heavenly host of delights on the road to hell. the Guardian.

Kennedy, M. (2015, October 21). Dutch museum achieves the impossible with new Hieronymus Bosch show. the Guardian.

Kruyswijk, M. (2016, April 26). 'Amsterdam dreigt te venetianiseren'. het Parool.

Kuiper, S. (2016, February 11). Mysterieus, fonkelend en mateloos fascinerend. de Vokskrant.

Netwerk Citymarketing. (2017). ’s-Hertogenbosch winnaar van zowel jury- als ook publieksprijs van de Netwerk Citymarketing Award 2017.

Pama, G. (2017, March 31). Jheronimus Bosch in top-10 best bezochte tentoonstellingen wereldwijd. NRC Handelsblad.

Provincie Noord-Brabant. (2015, December 16). Bosch Grand Tour in Brabantse musea.

Ribbens, A. (2016, December 14). 14.800 Bossche bollen en 150 miljoen euro. NRC Handelsblad.

Schoone, M. (2015). In gesprek met… burgemeester Ton Rombouts [Blog post].

SpotDenBosch. (2016, December 28). Jeroen Boschjaar stuwt bezoekersaantallen Brabantse musea op.

SpotDenBosch. (2016, December 28). Bosch blijvend verbinden aan zijn geboortestad Den Bosch.

SpotDenBosch. (2016, December 28). Jeroen Boschjaar stuwt bezoekersaantallen Brabantse musea op.

De Vries, J. (2017, February 14). Jeroen en Vincent, bedankt hè! Brabants toerisme is booming.

Van Vugt, H. (2016, March 19). Jeroen Boschjaar voor velen in Den Bosch lucratief en nu al succesvol.

Windhorst, P. P. (2014, October 1). Bossche Burgemeester Rombouts trok ongelovigen over de streep voor Jeroen Bosch-expositie.

Windhorst, P. P. (2016, November 17). Jeroen Bosch trekt dit jaar veel meer dan 1,2 miljoen bezoekers naar Den Bosch.

Zoetermeernieuws. (2017, February 17). Mondriaanjaar omlijst door jazz, design, dans en muurkunst.

’s-Gravesande, A., Van der Eerden, P., Duif, L., Smeets, M. E., Ploegmakers, M., Straatman, J., . . . Mandos, P. (2016). Annual Report 2015.