Proctorio and the Panopticon: Privacy issues during the pandemic

Tracking people is already a thing of the past - CCTV was developed in the 1920s and implemented in anti-crime efforts in the 60s. With the rise of digital media technologies and the Web 2.0, it is easier than ever to gather and store data about people, especially on social networking sites that often gather the real names of the users. Proctorio, the at-home exam monitoring plug-in, is only the latest digital surveillance tool.

Many of these platforms have faced criticism regarding their privacy policies. In 2018, Facebook gave companies access to user data without users' consent. However, people are also more likely to willingly give out their private information on the Internet, blurring the boundaries between private and public. In 2020, a global pandemic has forced most of us to continue our activities online, making us dependent on such technologies. In this article I will analyze how the pandemic has changed privacy. I will identify the Proctorio platform's privacy issues through the theoretical lens of Foucault's panopticon.

What is Proctorio?

Proctorio is a Chrome extension designed to monitor students’ behaviour during at-home exams in order to detect cheating and suspicious behaviour. This tool has been increasingly used during the 2020 pandemic, as education has moved online. However, Proctorio is able to record the student’s webcam and microphone together with everything that happens on screen. Usually teachers enable the webcam option so that students can always be watched. The algorithms then decide if a student is potentially cheating or not, which can lead to false accusations.

Proctorio has been under scrutiny for privacy violations due to its overly intrusive surveillance system, which makes use of eye tracking as well as head and mouth movement. Proctorio can be categorized as spyware, because it is programmed to monitor and record everything in the background, violating the user’s privacy. Proctorio users know that they are being monitored, but they cannot know when and what behaviour will trigger a response from the program. Furthermore, students have no choice but to use these types of software when taking exams at home. This means that although students might be aware of how invasive the spyware is, they cannot do anything about it.

Proctorio and the Panopticon

Once one has learned how this plug-in works, the comparison with the panopticon becomes relevant. The panopticon is a concept design created by the social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the 18th century. Its design consists of a round prison building with a tower in the center, from which a guard can watch over the cells placed along the wall. The guard's tower shines a light so that he can see everyone and everything, but the prisoners cannot see him. Anyone can become a guard, even an Artificial Intelligence such as Proctorio. The panopticon thus represents the ideal power system, where prisoners, never knowing when they are being watched, start to self-regulate and become their own prison guards: “It is an important mechanism, for it automatizes and disindividualizes power” (Foucault, 2008).

Proctorio is the same because students cannot really know what the plug-in does when running in the background or when it will register something as “suspicious.” Therefore as students feel constantly watched, they self-regulate and are less likely to cheat because they can be caught at any time.

A panopticon

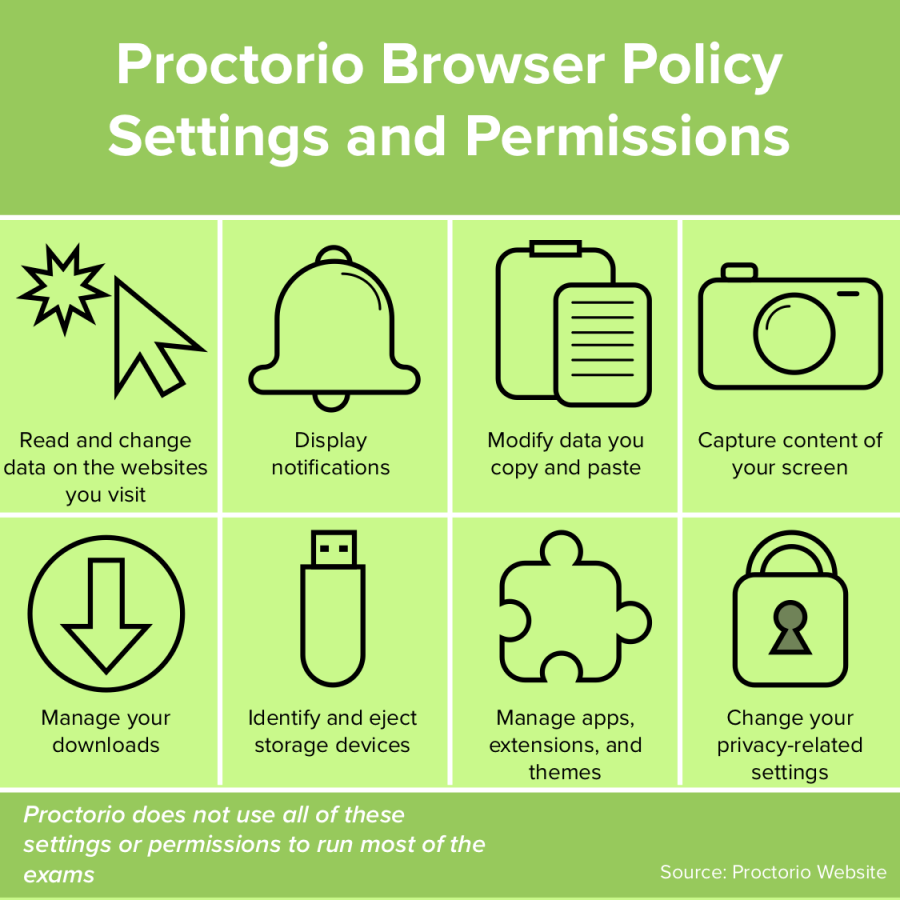

Proctorio permissions

After students have been tracked, the data on each student’s behaviour during the test is stored. This again can be compared to the design of the panopticon: the individual prison cells resemble the boxes of data that have been collected by the algorithm. There is one central watcher (Proctorio) and many individual cells (the users).

What would Foucault say?

In his work 'Panopticism from Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison', Foucault uses a plague-ridden town as a metaphor for idealized social control. This is relevant to the 2020 pandemic, especially parts of the world such as China, where citizens were already repressed by the regime: “China already has hundreds of millions of surveillance cameras in place” (Andersen, 2020). The internet has been flooded with videos of the extreme Chinese measures taken in January to combat the virus, and then again in March, when almost every country in the world had to enforce quarantine measures.

These measures have not changed much since the plague referenced by Foucault. Humanity has learned from its history: when there is an epidemic, closing down that place and imposing quarantine are seen as the most effective measures. However, getting people to adhere to these measures is the other side of the coin. This is where Foucault comes in handy. In order to impose such measures, a complete state of surveillance needs to be in place. In the 21st century this is easier to achieve due to high-tech surveillance systems such as location tracking, mobile number tracking, CCTV surveillance, COVID-19 apps, and, of course, Proctorio. All these technologies can create a Panopticon: big brother is watching us, we do not know when, but this possibility makes us behave accordingly and obey Covid-19 regulations.

The Covid-19 pandemic has had two major impacts on privacy: first is that the private safe-space of the home has become a working place. Second, digital tracking has skyrocketed in the form of apps such as Proctorio or apps designed to track Covid patients in order to contain the spread of the virus (CoronaMelder in the Netherlands). Thus, the way this pandemic has unfolded is eerily similar to Foucault’s arguments. Foucault makes use of the plagued town as an example of control. He then goes on to talk about the implementation of the panopticon in institutions like the asylum, the hospital or the prison. The pandemic and an increasingly-surveillant capitalist society show that currently we experience a loss of privacy.

According to Foucault, in the plague-struck town, “the gaze is alert everywhere” (Foucault, 2008). However, this gaze has become personalized by increased bureaucratization and more recent digitalization of our lives. “Generally speaking all the authorities exercising individual control function according to a double mode; that of binary division and branding (mad/sane; dangerous/harmless; normal/abnormal); and that of coercive assignment, of differential distribution (who he is; where he must be; how he is to be characterized; how he is to be recognized; how a constant surveillance is to be exercised over him in an individual way, etc.)” (Foucault, 2008). We can apply this to the current situation: people are either covid-negative or covid-positive. In the case of Proctorio’s AI surveillance system, students are either honest or cheaters.

Foucault refers to the panopticon's simplicity: “because, without any physical instrument other than architecture and geometry, it acts directly on individuals; it gives ‘power of mind over mind’” (Foucault, 2008). With major technological advancements, the panopticon does not need to be a physical place, and it does not even need human intervention. Proctorio is a metaphysical panopticon operated by an AI. The ease with which such apps or platforms operate would have been deeply criticized by Foucault, as they can achieve constant surveillance and exercise power over users.

Student responses to Proctorio

Comparing Proctorio to the panopticon makes it easier to understand why it is such a threat to privacy and intimacy. As students are doing everything from home, their relaxing space has become their work space. Therefore Proctorio's intrusion turns their rooms into fully-fledged panopticons. Students' eye and head movements are constantly tracked, and even looking away from the computer might potentially disqualify a student. Students cannot act naturally for fear of being discredited.

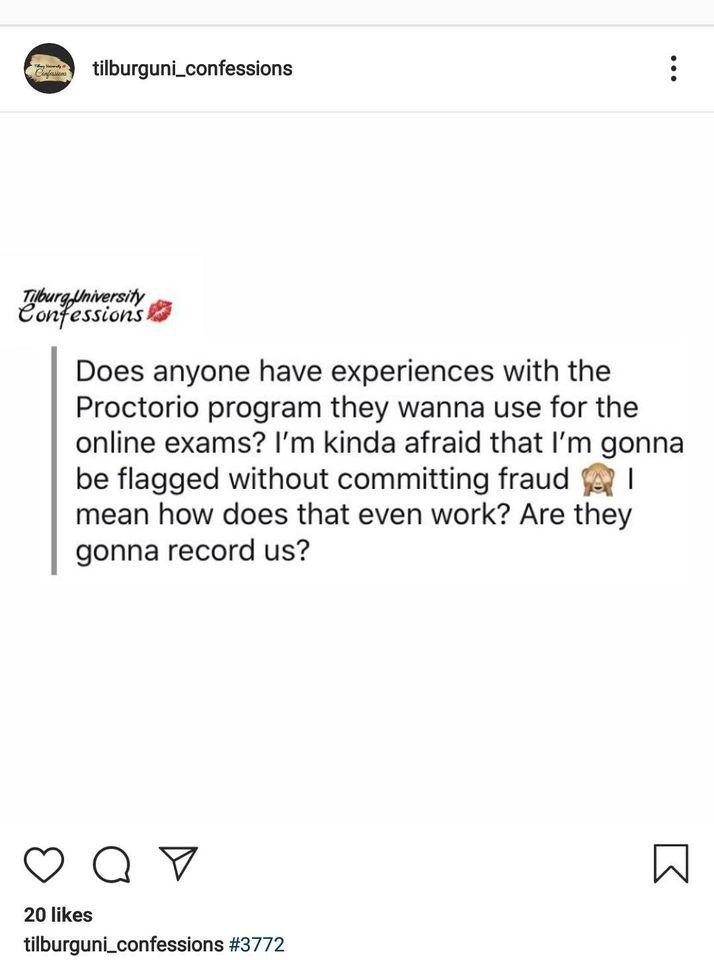

There have been many responses to the privacy issues raised by Proctorio. For instance, the University of California, Santa Barbara, raised concerns about ProctorU (a similar software, but regulated by humans instead of AI), arguing that it violates students' right to privacy. At Tilburg University, similar concerns were raised about Proctorio, by teachers and students. Studentes even complained about Proctorio on an anonymous Instagram confessions page (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3

Figure 4

Importantly, Proctorio's CEO has already been involved in a scandal after posting a student's chat logs on Reddit to make a point in an argument. Such an event clearly demonstrates that Proctorio violates user privacy. Proctorio claims that they respect user privacy in their Terms of Service (ToS), but the fact that the CEO posted student chat-logs on a public forum shows a certain hypocrisy.

On their website, Proctorio claims that “Proctorio does not disseminate personal information to third parties for any use. All data that enters our system has been encrypted using an unshared key stored in the learning management system (LMS) and can only be unlocked by authorized users within the LMS.” This does not necessarily mean that data is safe with them. There is always a risk of data breaches and hacked servers. Even so, trusting Proctorio to store your browsing information and videos of your room, does not sound good when put in perspective.

Other problems that programs such as Proctorio might create arise from bias or incapacity to adapt to different situations. For instance, people with disabilities (such as facial tics), people who live with children in the house (increased noise), and even people of colour might face problems when using this software. For example, people of a darker skin tone are sometimes not recognized by such platforms (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Proctorio: An Orwellian Big-Brother?

Proctorio is a plug-in that is needed in online education, but violates students’ privacy. Much as spyware would do, Proctorio stores personal data, and users have to simply trust that their data is safe. Proctorio is thus yet another convenient platform designed to offer an important service at the price of our data and, implicitly, our privacy.

The pandemic has made it hard for people to maintain their privacy as students and employees are forced to merge their working space with their comfortable homes. In this way, the boundaries between private and public life are more easily crossed. Employers and teachers want to ensure that people are working and that students are not cheating. Everything has moved online; our entire existence takes place in the same room. The only way to check on people is by using software designed to monitor our private houses. If students cannot even look through the window, thinking quietly on their tests, without being accused of cheating by a biased algorithm, then the importance of privacy is jeopardized.

As such platforms make their way into people’s lives I believe that we are getting closer to an Orwellian Big Brother scenario. Proctorio tracks everything, sees everything, hears everything, and is virtually untouchable. Fair comparison, right? Apps such as Proctorio might be useful in controlling students and ensuring exam integrity, but at what cost? The distinction between a student’s private life and academic life is endangered as more and more universities demand their students make use of such software, or rather, spyware.

References

Andersen, R. (2020). China’s Artificial Intelligence Surveillance State Goes Global. The Atlantic.

Foucault, M. (2008). "Panopticism" from "Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison". Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts, 2(1), 1-12.