Healing Properties of Books: Ukrainian Children’s Literature on War and Displacement

Political and military conflicts affect not only the everyday lives of adults but also children and teenagers who have to acknowledge that air alarms, missile explosions, rubble of destroyed buildings and fleeing from the country are a part of their ‘new reality’. Since the full-scale Russian invasion in 2022, 7.9 million Ukrainians fled the country and 35% of this number are children, 4.8 million citizens are internally displaced and almost every single child has faced the horrible atrocities of war (UNHCR, 2022).

Moreover, children live in a highly saturated and digitalized world where they have access to gruesome news and images of war from either more traditional means of communication – conversations with family members and friends, TV and radio news and printed newspapers – or new digital sources such as websites, social media, etc. Such dense news coverage is subjected to the issue of misinformation, manipulations and even cases of psychological operations (PSYOP) which require a high degree of critical thinking and media literacy from news consumers.

Therefore, there is a need for literary sources with war narratives for Ukrainian children that provide readers with realistic reflections and explanations of the war atrocities and a safe space for contemplation, escape and emotional support; as well as equip caretakers and other educational gatekeepers with tools and strategies on how to interact and communicate with children while reading such books.

Children's Book as Safe Space

Children’s literature has the potential to facilitate safe spaces where tensions and issues connected with war and displacement can be addressed with care (McAdam et al., 2020) and resolved with the help of self-reflection, therapeutic art practices, as well as by having meaningful discussions with parents, educators and psychologists. Prior to selecting the literary materials for the book curation, I drew on a collaborative work of experts from the Laboratory of Children’s Literature “Barabooka”, Ukrainian Book Institute and NGO Smart Osvita which was encapsulated in a manual called “Living Writers. How to talk with children about war and peace” (2023). The manual is published in Ukrainian and its original name is «Живі письменники. Як говорити з дітьми про війну та мир» (2023). All translations from Ukrainian are done by the author of this paper.

The war undermines the child's sense of trust in the world and in adults, the sense of stability and normality of the world. Reading and having conversations with children bring back these feelings (Stus, 2023, p. 14).

This manual systematizes the studies of literary experts, psychologists and historians on the topic of how to talk with children and teenagers about war and peace through the medium of literature. Moreover, it offers educators, librarians and parents tools to facilitate war experiences and traumatic events through the literary works of modern writers who have been writing about the Russian-Ukrainian war since 2014. Tania Stus, a writer and organizer of Barabooka, together with children’s psychologist Svitlana Roiz (2023, p. 4) emphasizes the value of “reading and contact with the book in accompanying children and teenagers in the dangerous experiences of war and in rethinking these experiences” as it produces an active response from within and can serve as a way of dealing with trauma. All traumatic experiences are individual and unique in their essence, and therefore should be approached with care and respect. However, Roiz introduces the sense of control manifested in the physicality of books which can serve as a counterpoint to trauma as “the war undermines the child's sense of trust in the world and in adults, the sense of stability and normality of the world. Reading and having conversations with children bring back these feelings” (Stus, 2023, p. 14).

Apart from the physicality of the book and the physical presence of an adult that could have a soothing effect on children, Roiz mentions truth as a key tool for dealing with trauma, as “truth heals and it creates a whole picture” (Stus, 2023, p. 23) of the situation; though the way how the truth is approached and presented for children should be assessed on an individual level depending on what traumatic experience children have acquired after witnessing missile shelling, fleeing from the country, etc. The infamous Rudine Sims Bishop’s metaphor of mirrors, windows and doors (1990), especially the first part – mirrors – illustrates the potential of children’s literature on war as a productive vehicle for healing and having constructive discussions about the current state of the environment children live in. By treating war narratives as mirrors, children and caretakers can interact, reflect on, as well as agree and disagree with fictional characters and settings (McAdam et al., 2020). Fictional narratives with war elements have the ability to erase and create distance between the reader, the narrative and the real world where readers live; therefore, such literature works as a safe space for exploration and means for escapism from reality. Besides, such texts with metaphors and illustrations can serve as a shared ground between children and adults when they discuss the gruesome consequences of war; they help to omit misunderstandings and unreasonable fears; ultimately, they allow children to be more in control of the situation and form their own understanding.

Finally, children’s literature about war and displacement is not only about the war but also about peace as the ultimate representation and outcome of hope. Putting aside simplistic naïve and unsophisticated forms of hope which are embodied in “one who hopes for the sake of hoping” (Webb, 2010. p. 328), critical hope is capable of producing a desire to explore, learn and examine possible problem-solution tensions. Hope is not only about a happy ending; instead, it is placed on a gliding scale where between point A and point B there is a lot of space for growth and contemplation. Therefore, reading and talking about peace is another instrument in talking with children about war; peace is a larger phenomenon than a victory which has a sense of finality and fear of uncertainty, and “it provides space for asking questions about finding resources and ways to live in a soon-to-be new world” (Stus, 2023, p. 5) which will never be the same.

Criteria for selecting the books

Since being directly affected by the Russian-Ukrainian war, I decided to resort to Kathy G. Short’s (2019) critical content analysis guiding points in order to have a critical eye on the scope of Ukrainian books and not fall into the trap of subjective judgments based on my personal experience and trauma. Especially, the concept of a critical stance that “focuses on voice and who gets to speak, whose story is told, and in what ways” (Short, 2019. p. 5) helped me outline the next four main criteria that I followed during the selection process.

- Acquiring a critical lens based on the chosen theoretical concepts, such as Roiz’s ideas of dealing with trauma via accepting truth and Bishop’s metaphor of children’s literature as mirrors for readers.

- Selecting the target audience. The curation has a double target audience: children as potential readers and adults who can use the texts in classrooms, reading clubs or at home.

- Books that transmit hope for peace and rebuilding, rather than an imaginary ‘happy end’. The opposition ‘war vs. victory’ creates temporal and spatial limitations and unfulfilled expectations of the expected moment of joy (Stus, 2023). Putting into the limelight peace and inevitable changes in post-war life eliminates the sense of finality and highlights the idea that life continues no matter what.

- Literature as a safe space for distancing and escaping from reality. Despite the first criterion, I still looked at war narratives in Ukrainian picture books with fairy tale and fantasy elements that might provide more distance between the narrative and the real reader and could serve as examples of universal books on war relatable to a wider audience.

Case study 1: “Залізницею додому” [Eng. transl,. “Going Back Home By Train”], a picture book on displacement

Mariana Savka’s picture book Going Back Home By Train (2022) is a moving story of fleeing from Ukraine during the first days of the Russian full-scale invasion. The story is told in first-person narration: Eva is a girl who shares her experience of being evacuated to Krakow, Poland, together with her mother and family friends in February 2022, returning home and subsequently readjusting to new (old) life in Ukraine with air alarms and danger of missile shelling.

The front cover and a page spread from Mariana Savka’s picture book "Залізницею додому" (2022) [Eng. transl., Going Back Home By Train].

Life in another country and reasons for coming back home are not mentioned explicitly. Apart from the realistic depiction of characters fleeing from Ukraine and the use of different visual symbols of Ukraine (the illustration shows a page spread from the picture book with a watermelon as a symbol of the southern part of Ukraine – occupied and partially liberated region of Kherson which is known for its watermelons), the picture book consists of therapeutic art practices intended for children to reflect on their experience and visually represent their thoughts, fears and emotions. For example, there is a full-page spread called “Draw Your Journey” (Savka, 2022) which encourages readers to use any stationary tools to draw or paint their evacuation in any form or shape they want; children can complete their task on their own or together with adults’ assistance and it can also serve as a post-reading task and conversation where children are invited to interpret their drawings.

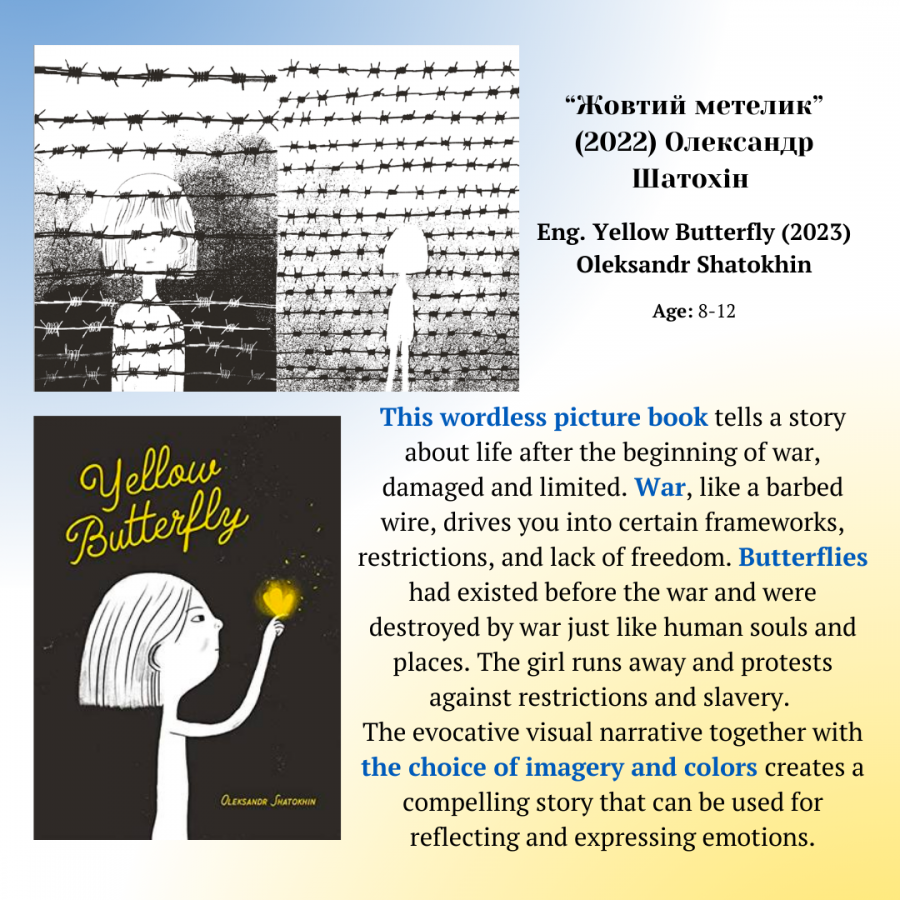

Case Study 2: Yellow Butterfly, a wordless picture book as a universal source for healing

The wordless picture book Yellow Butterfly (2023) by Oleksandr Shatokhin is a wordless picture book about life after war, broken and limited by the outcomes of destruction.

The front cover and a page spread from Oleksandr Shatokhin's wordless picture book "Yellow Butterly".

The barbed wire is an image of limitations and restraints and the fear that war gives. This picture book is selected as an example of how the interplay of images and contrasting colours of black buildings, barbed wire and explosions against a bright yellow butterfly can broadcast universal ideas: war brings destruction, and the yellow butterfly represents hope and courageous people. The main aim of this story is to provide space for contemplation and reassure the readers that there are new beginnings amidst the chaos and darkness. Maybe not a classical happy ending, but a sparkle of hope for rebuilding and prosperity.

Further Reading

Apart from the two case studies, I have chosen three other picture books which tick all the boxes of the selection criteria:

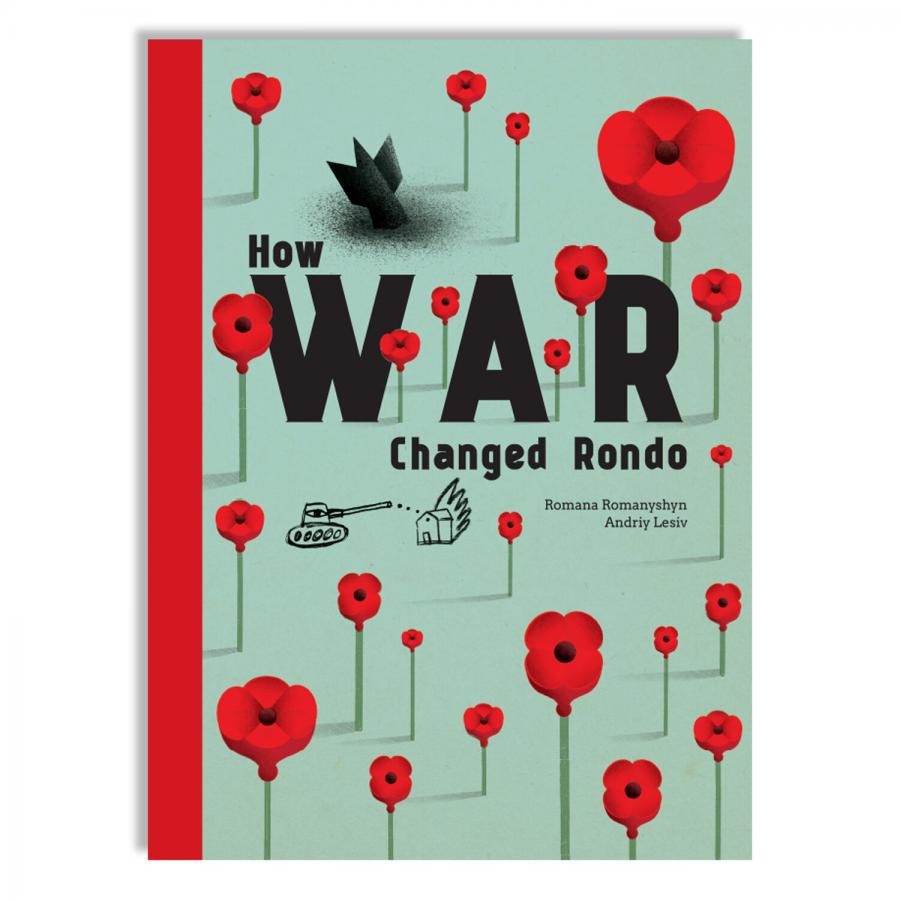

How War Changed Rondo (2021) by Romana Romanyshyn and Andrii Lesiv

Danko, Zirka, and Fabian live peacefully in the small town of Rondo, a magical and joyful place where even the flowers sing! Everything is perfect until the fateful day when War arrives. How War Changed Rondo reflects the darkness and pain that conflicts bring and the wounds that linger long after everything’s over. This picture book serves as a tribute to peace, resistance, and hope.

The book cover of "How War Changed Rondo" (2021) by Romana Romanyshyn and Andrii Lesiv.

Due to its universality and fairytale narrative, the story serves as an entry point for discussions about war, its atrocities, losses, traumatic experiences and their consequences.

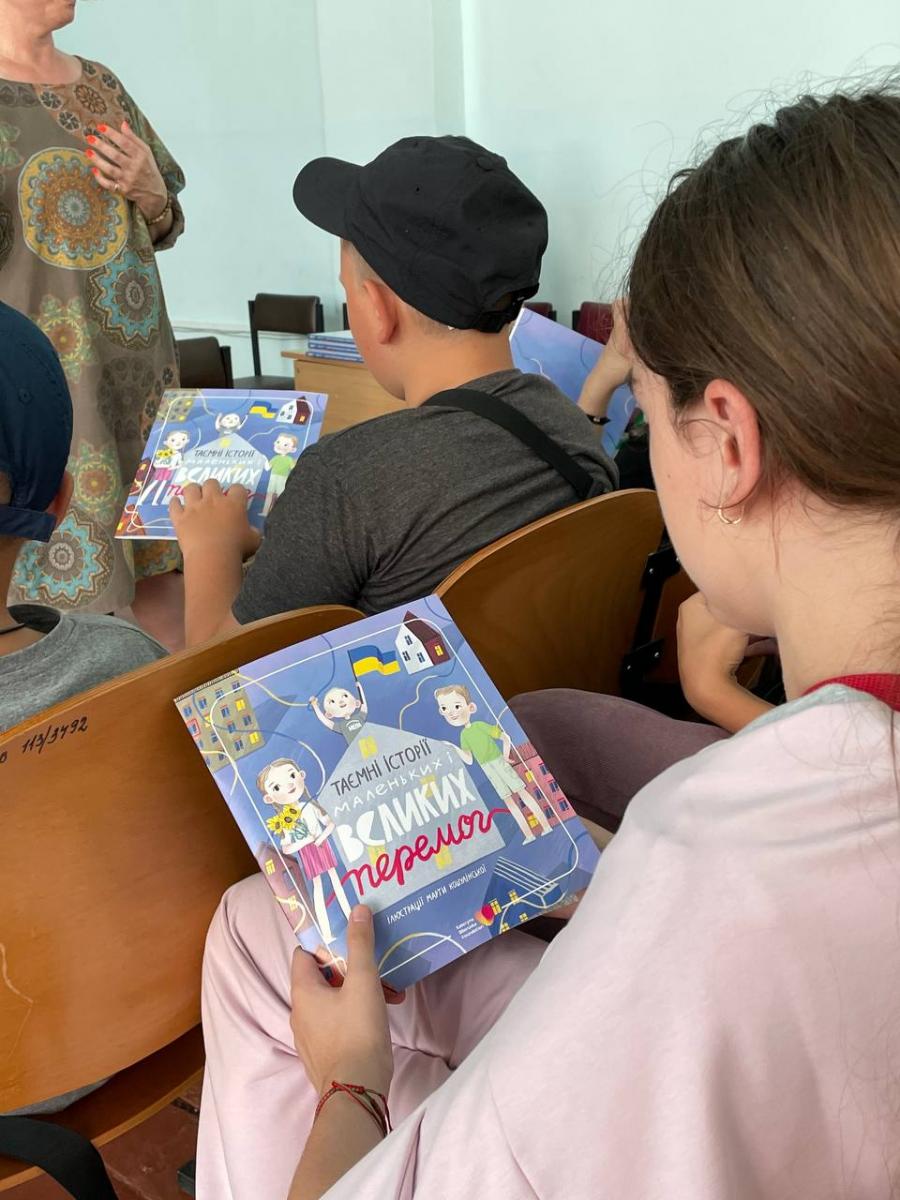

“Таємні історії маленьких та великих перемог” (2023) by Tania Stus [Eng. transl., “Secret Stories of Small and Great Victories” (2023)]

The book consists of ten stories with a therapeutic effect about children's experience of witnessing the events of the Russian-Ukrainian war. Each story consists of two parts - realistic and fairy-tale, that allow the reader to imagine a certain situation and find a way to look at it through the prism of fairy-tale perception.

Ukrainian pupils have a meeting with the author Tania Stus at Sokal Sanatorium Boarding School in Lviv region. Stus read together with the students some excerpts from her therapeutic book [Eng. transl., Secret Stories of Small and Great Victories].

The stories carefully and delicately depict the themes of loss of home, relocation, adaptation, emotional experiences, aggression, longing for family belongings, disability or death of soldiers, and waiting for victory.

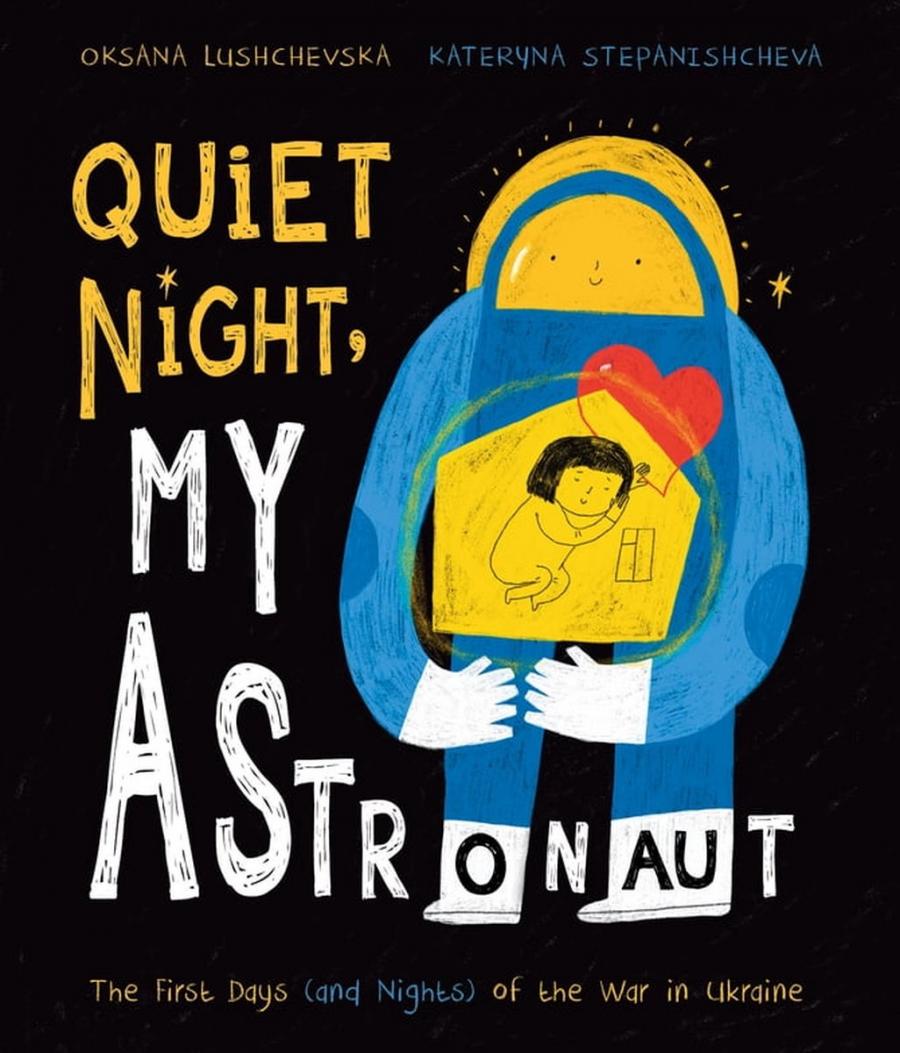

Quiet Night, My Astronaut: The First Days (and Nights) of the War in Ukraine (2024) by Oksana Lushchevska

It is a picture book in the form of a child's diary. The main character is a seven-year-old girl, Iya, who writes down notes during the first ten days of the Russian invasion. The story contains details of Iya's daily life during the war, her worries, dreams and beliefs filled with a variety of emotions such as fear, confusion, joy and despair. An imaginary astronaut helps Iya to hold on.

The book cover of English translation of the Ukrainian picture book "Quiet Night, My Astronaut: The First Days (and Nights) of the War in Ukraine" (2024) by Oksana Lushchevska. This edition was released in February, 2024.

Through vibrant and symbolic illustrations and diary entries, the readers can reflect on drastic changes in Iya's and their lives, as well as find hope and courage to hold on during this difficult time.

Conclusion

This list of Ukrainian children’s books on war and displacement can be expanded as there is still a nascent need and the Ukrainian book market supports the production of such literature. Nevertheless, I hope that these books provide an entry point for both children and adults who have been affected by war and are in need of healing and solace, as there is a critical need for literature tailored to Ukrainian children, offering realistic depictions and explanations of war atrocities. Such literary works should serve as a safe space for contemplation, escape, and emotional support, providing a nuanced understanding of the complexities of war. Furthermore, caretakers and educational gatekeepers must be equipped with tools and strategies to engage with children while reading these books, fostering a supportive environment for processing the traumatic experiences they may have endured.

References

Arizpe, E., Farrell, M. and McAdam, J. (2013). Opening the Classroom Door to Children’s Literature: A Review of Research. pp.241–257.

Bishop, R.S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 6, ix–xi.

Lushchevska, O. (2024). Quiet Night, My Astronaut: The First Days (and Nights) of the War in Ukraine. Tilbury House Publishers.

McAdam, J.E., Abou Ghaida, S., Arizpe, E., Hirsu, L. and Motawy, Y. (2020). Children’s Literature in Critical Contexts of Displacement: Exploring the Value of Hope. Education Sciences, 10(12), p.383.

Old Lion Publishing House. (2021). What Does War Feel Like to a Child? The New York Times about ‘How War Changed Rondo’. [online]

Romanyshyn, R. (2021). How War Changed Rondo. Enchanted Lion Books.

Savka, M. (2022). Going Back Home By Train. The Old Lion Publishing House. [Ukr. Савка, М. (2022).Залізницею додому. Видавництво Старого Лева.]

Shatokhin, O. (2023). Yellow Butterfly. Red Comet Press.

Short, K.G. (2016). Critical Content Analysis as a Research Methodology. In: H. Johnson, J. Mathis and K.G. Short, eds., Critical Content Analysis of Children’s and Young Adult Literature: Reframing Perspective. New York: Routledge, pp.1–15.

Stus, T. (2023). Secret Stories of Small and Great Victories. Knygolove.

Стус, Т. (2023). Таємні історії маленьких та великих перемог. Книголав.

Stus, T., Tretiak, A. and Artemenko, M. eds., (2023). Living Writers. How to talk with children about war and peace. [online] Ukrainian Book Institute.

Стус, Т., Третяк, А. and Артеменко, М. eds., (2023). Живі письменники. Як говорити з дітьми про війну та мир). Український інститут книги.

UNHCR (2022). Ukraine Refugee Situation. [online] data.unhcr.org.

Webb, D. (2010). Paulo Freire and ‘the need for a kind of education in hope’. Cambridge Journal of Education, 40(4), pp.327–339.