Maastricht University sued for being too "international"

The debate about the increasing Anglicization in Dutch higher education

The political debate about the advantages and disadvantages of the increasing internationalization in Dutch higher education, specifically the increasing use of English, has been going on for a couple of years now. It recently became quite controversial as the organization Beter Onderwijs Nederland (Better Education Netherlands) was planning on suing universities in the Netherlands for implementing English as a working language without any valid reasoning for doing so (Ligtvoet, 2018).

English as a teaching language in the Higher Education Law

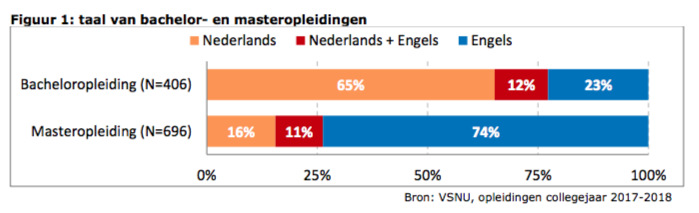

The number of study programs in Dutch higher education in which instruction is provided in English has increased tremendously in the last couple of years. This especially holds true for master programs as the majority, 74% to be exact, is now in English (VSNU, 2017; see Figure 1). The choice for this language is mostly based on a desire to create an international classroom: a mixed group of Dutch and international students.

This increased Anglicization however, has given rise to much debate about the positive and negative sides of this matter. The Dutch Minister of Education, Ingrid van Engelshoven, has just released her vision regarding this subject and stated that she wants to modernize the Higher Education Law. She wants to amend the language part of the law from allowing another language to be used “only if there is a necessary reason” to allowing it to be used “if it is of added value” (Bouma & Meijer, 2018). This however did not stop the discussion about whether or not English should be included in education.

Image 1: The percentages of number of bachelor- en masterstudies in English and/or Dutch.

The contradictions and decisions in this debate about what language of instruction is legitimate in higher education brings us to the fundamental goal of a language policy, which is the production and consequent enforcement of a specific set of norms for language use in a certain institutionalized environment within a given state (Kroon & Spotti, 2011). It is specifically about choices with regard to what languages will serve what functions. The opinions of the actors involved differ on whether English should be granted the status of a language of instruction or not.

Teachers cannot keep up with the pace of learning and teaching in English and as a consequence the quality of instruction decreases.

This article dives deeper into this debate by discussing some of the viewpoints, focusing on the Dutch government, Beter Onderwijs Nederland, the media, and one of the universities that is under fire: Maastricht University. These views will consequently be analyzed and linked to relevant theories on language policy making. In doing so, the main question will be how the debate about English as a language of instruction in higher education can be placed and understood as part of the language policy process.

In favor or against internationalization?

As stated before, the Minister of Education recently released her vision regarding the use of English in higher education. She wants to give English more space through a revision of the Higher Education Law with respect to the language of instruction. At the same time however, she wants to monitor the latter and she wants to constrain the influx of international students. Van Engelshoven wants to monitor whether educational institutions transfer to English for sufficient reasons and if the teachers' proficiency level of English is high enough.

Regarding the number of international students, she wants to implement a numerus fixus for English tracks of study programs. According to Van Engelshoven it must be possible to have variety in educational languages (Van Engelshoven, 2018). She states that this view is in line with the study conducted on her request by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) into language choice and language policy in Dutch higher education, mainly focusing on the choice between English and Dutch. The study looked at arguments from different angles and concluded that there are four main points of attention for higher educational institutions to consider when making language choices and developing a language policy (KNAW, 2017).

- First of all, when choosing a language of instruction this must be a conscious choice keeping in mind the specific objectives of the study program.

- Second, the language of instruction should be decided at the departmental or program level.

- Third, when choosing English as a language of instruction, institutions should be well aware of the associated costs and benefits, and the advantages and disadvantages.

- Fourth and finally, such a decision should be firmly anchored in a supportive language and internationalization policy (KNAW, 2017).

Keeping these remarks in mind, Van Engelshoven is in favor of including English as a language of instruction and she wants the internationalization process to continue.

According to Minister Van Engelshoven it must be possible to have variety in educational languages.

This however did not stop Beter Onderwijs Nederlands’ (BON) lawsuit against universities in the Netherlands. Even though the statements made by Van Engelshoven could suppress their lawsuit, as BON’s core argument is based on the current law that the Minister wants to amend, BON will still continue the ‘fight’ against Anglicization, because they do not trust that the adjustments suggested by Van Engelshoven will change the situation for the better (Beter Onderwijs Nederland, 2018).

According to BON, the reasons for using English are inadequate at certain universities in the Netherlands as they say universities are mostly switching to English to bring in more international students and therefore more money. BON wants to stop the Anglicization process, because it believes that Anglicization puts pressure on the quality of education as, according to them, both teachers and students cannot express themselves that well in English.

BON moreover believes that the increasing use of English has negative consequences for the students’ Dutch language skills. BON is accusing universities of setting a bad example and of neglecting their societal role (Ligtvoet, 2018). Their suggestion and solution is to keep Dutch as the working language and address the English language in separate subjects.

The opinions on this matter in public debate are divided. Some find that BON completely ignores the advantages that Anglicization has to offer. Marc van Oostendorp, researcher at the KNAW, argues that it offers a “fresh” look as it brings more perspectives and viewpoints from all over the world and this can better the entire society (Van Oostendorp, 2017). He states that it is an erroneous idea to think that the Netherlands is a monolingual society and argues that both the Dutch and English language should be granted an important status in higher education.

Others also find it logical that academic institutions increase their use of English, as in reality English serves as a lingua franca in most scientific research and therefore the use of English is not only argumentative but also imperative (“UM gedaagd”, 2018). But the rapid increase in the use of English also has a downside as most teachers cannot keep up with the pace of learning and teaching in a new language, and therefore the quality of instruction could decrease. The latter is reflected by the opinion of university students who are by far not satisfied with the English teaching qualities of their lecturers (ANP, 2017). But not only teachers are criticized for their level of English, students themselves are often accused of lacking language proficiency (Hekkens, 2018).

Maastricht University sued for teaching in English

One of the universities that is being confronted about its language policies is Maastricht University. Maastricht University is the youngest and most international university of the Netherlands. Out of its 16,861 students, 51% come from abroad. The university is bilingual, but currently most education is provided in English. The presence of the English language is also visible in the linguistic landscape, as can be seen from Figures 2 and 3.

Image 2: A bilingual garbage bin

Image 3: An English written anouncement in the UM library

Maastricht University completely disagrees with the arguments made by BON. Martin Paul, Chairman of the Executive Board, states that the university has always been identified in an international context due to its location and therefore develops its strategies and policies according to this (Paul, 2018). It has no doubts about its internationalization-strategy and will continue to implement this vision in the future. Also, because it is simply unavoidable in 2018. The Executive Board declares that their choice of language is always one of considerable thought, in which quality of education comes first (personal communication, May 18, 2018). This is in line with their language code that states that there have to be sufficient reasons if English is chosen as the language of instruction and if so, the quality and study load of the program must be equal to that of Dutch-language programs (Maastricht University, 2018).

At Maastricht University all lecturers have to pass a test to prove that they are highly fluent in the foreign language in which they teach.

But Maastricht University does not just disagree with the critique about their language policy. As of next September, a stricter language policy will be implemented (Bos, 2018). All lecturers have to pass a test to prove that they are highly fluent in the foreign language in which they teach, and Dutch students can do a course in Dutch academic writing. The university plans to implement this policy to enhance their position in the national debate about the Anglicization of higher education.

What function for what language?

As becomes clear from the above, the discussion about the advantages and disadvantages of the increasing internationalization in Dutch higher education, specifically the increasing use of English, is basically a debate about what language can be used in a certain environment; it is about what language should be the language of instruction or even broader, the working language in higher education.

The current language policy does not dictate that the English language is not allowed, it just dictates that is has to be used for good reasons. The opinions of the actors involved (the government, BON, the media, and Maastricht University) are divided on these reasons and therefore on whether English should be granted the status of a working language in higher education or not. This refers to the status planning aspect of language policy, which is related to what function you give to a language (Kroon, 2000). It is about “deliberate efforts to influence the allocation of functions among a community’s language” (p. 8). Status planning is a societal choice, a choice made by the government. And such choices cannot escape from taking a position in societal and political discussions (Kroon, 2000).

Language policy therefore is a social phenomenon, depending on the beliefs and consensual behaviors of members of a speech community (Spolsky, 2009). The English language in this debate is either seen as a resource, i.e. linguistic diversity is a possible and desirable form of capital, or as a problem, i.e. it is perceived as a kind of handicap, something that hinders the enhancement of Dutch language abilities (Kroon & Vallen, 2006). Depending on how a specific language is seen, a specific status will be granted to it or not. The Minister looked at the different points of view and decided to monitor the increasing use of English more sharply but also to amend and modernize the law in order to give the English language more space. In this way she sees linguistic diversity as a resource, and with that she grants universities more freedom in choosing and implementing their preferred working language.

In the middle of the policy cycle

The current discussion about language policy in higher education can be analyzed in terms of the policy cycle. This is an ideal-typical process through which policies come into existence (Kroon, 2000). The current policy has existed for a long time and has been implemented by universities according to their own understanding.

Due to the discussion about the increasing Anglicization however, more attention was brought to the implementation process of the language policy and this made the Minister to request a study by the KNAW which led to some points for institutions to consider when making language choices and developing language policies.

BON and some media critics also evaluated the implementation process and do not think that the language policy is being carried out in the correct way. They looked at the aims and means of the policy plan. According to BON and other critics, universities are not switching to English for internationalization reasons in favor of students’ education, but for the aim to bring in more money by means of offering more programs in English. They are afraid that the English language will harm the quality of education, and therefore want to stop the Anglicization process.

This brings us to the concept of dangerous multilingualism (Kroon & Spotti, 2011) in which linguistic diversity is seen as something dangerous as it represents a potential threat to the uniformity and cohesion of educational institutions. We saw that Maastricht University does not agree with these arguments, as they state that their implementation of language policy is always one of considerable thought. But they do take the evaluation judgements in mind since they are implementing a stricter language policy to meet with the criticism they received.

According to BON universities are mostly switching to English to bring in more international students and therefore more money.

The feedback that was retrieved by looking at different viewpoints made the Minister of Education, the policymaker, change the original plan which brings us back to the first step of the policy cycle: ideology formation (Kroon, 2000). Achieving full agreement with respect to the question whether the existence of individual and societal multilingualism has to be considered a resource or a problem often turns out to be very different.

That is why actors in policy making often content themselves with reaching a partial agreement. We can clearly see this reflected in this particular case as the Minister made a decision that was not in favor of all parties involved. She is modernizing the language law of higher education not in favor of the opponents of Anglicization, but more in line with the advocates. BON is holding on to the norms and values on which the original policy was based and argues that Anglicization should be seen as a problem, whereas Van Engelshoven seems to look more at current Dutch society in which multilingualism is inevitable.

As Van Oostendorp (2017) argues, it is an illusion to think that the Netherlands is a monolingual country. It marks the chronotopical setting of a policy: policies are always based on an ideology that is tied to a certain time and place If this situation changes, the policy changes, because that language policy is not a reflection of reality anymore. And the situation has changed in the Netherlands. More educational programs are offered in English compared to a couple of years ago, which leads to the inevitable fact that the original language policy does not match the reality anymore.

Different views but one conclusion

This article examined the debate about what language should serve what function in higher education. As the viewpoints of the actors discussed above make clear, there is a lot of contradiction about whether multilingualism, specifically the presence of both Dutch and English, should be considered as a resource or a problem. The language policy process is always one of discussion, contradiction, and renewal. The implementation of the current law by educational institutions led to much debate about the advantages and disadvantages of the increasing internationalization in Dutch higher education, which created a division between opponents and advocates, which eventually led to an evaluation and adjustment of the current policy.

Minister Van Engelshoven chose to see English as a resource, not as a problem.

In the end, decisions will be made at the top, and they cannot escape from taking a position. The Minister chose to see English as a resource, not as a problem. It is however important, as Van Engelshoven already suggested herself, to keep monitoring its implementation to make sure that English is used because it is of added value. But to the opponents in this debate: you cannot make the English language disappear. English is very much present, and will be in the future, and so you have to deal with it in your language policies.

References

ANP (2017, November 15). Keuzegids: wisselend niveau Engels op universiteiten. Nederlandse Omroep Stichting.

Beter Onderwijs Nederland. (2018, May 18). BON sleept universiteiten voor rechter [Press release].

Bos, W. (2018, April 25). Stricter language policy. Observant.

Bouma, K., & Meijer, R. (2018, June 4). Minister van Engelshoven: ‘meer ruimte voor, maar ook meer toezicht op Engels in hoger onderwijs’. De Volkskrant.

Hekkens, P. (2018, June 6). Engels met de haren erbij gesleept. Dagblad de Limburger.

KNAW. (2017). Nederlands en/of Engels? Taalkeuze met Beleid in het Nederlands Hoger Onderwijs. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: KNAW.

Kroon, S. (2000). Language policy development in multilingual societies. In M. den Elt, & T. van der Meer (Eds.), Nationalities and Education: Perspectives in policy-making in Russia and the Netherlands: Issues and methods in language policy and school-parents relationship (pp. 15-38). Utrecht: Sardes.

Kroon, S., & Vallen, T. (2006). Immigrant Language Education. In: K. Brown (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, (pp. 554-557). Oxford: Elsevier.

Kroon, S., & Spotti, M. (2011). Immigrant minority language teaching policies and practices in The Netherlands: Policing dangerous multilingualism. In V. Domovic, S. Gehrmann, M. Krü ger-Potratz and A. Petrovic (Eds), Europäische Bildung: Konzepte und Perspektiven aus fünf Ländern (pp. 87-103). Münster: Waxmann.

Ligtvoet, F. (2018, May 17). Universiteiten voor de rechter, want ‘oprukkend Engels moet stoppen’. Nederlandse Omroep Stichting.

Maastricht University. (2018). Code of Conduct for Language at Maastricht University.

Paul, M. (2018, May 26). Word wie je bent. Dagblad de Limburger.

Spolsky, B. (2009). Language management. New York: Cambridge University Press.

UM gedaagd. (2018, May 19). Dagblad de Limburger.

Van Engelshoven, I. (2018, June 4). Internationalisering in evenwicht [Letter to the Dutch Parliament].

Van Oostendorp, M. (2017, July 5). Niet minder maar meer Engels in het onderwijs. NRC.

VSNU. (2017). Factsheet: Taalbeleid universiteiten.