When the villain looks cool: how the World Press Photo 2017 deceives us

An Assassination in Turkey, the photograph taken by Burhan Özbilici, featuring the assassin of Russia’s ambassador to Turkey in Ankara last December, has won World Press Photo (WPP) of the Year 2017. Opinions on this top prize are divided. Stuart Franklin, chair of the general jury of the prestigious photo contest, voted against it. While praising the photographer’s bravery and professionalism, he is concerned about the moral risk of amplifying a terrorist message. Other jury members are convinced that the picture powerfully represents current issues in the world. “It is the face of hatred”, said João Silva.

This photo is indeed the face of our time, just not one of hatred. Rather, it refers to our media-saturated world, our appetite for sensationalism and spectacular violence in pop culture. It says more about our gaze than about what it captures. And if there is one thing that it reveals, it is that the world is not always so black and white.

Aesthetics over documentary

There is a young man in dark suit and black tie who very much resembles one of those “cool” mobsters from Tarantino’s cult film Reservoir Dogs. The killing is done, but not a single drop of blood stains the shiny floor and the stark white wall. The scene is unusually clean for a deadly attack, almost artificial, like a theater stage or a film set. We do not only see a murder, but also a spectacle, as if the killer is also a performer, aware of the gaze laid upon him. The cruelty of the event is overshadowed by its theatrical depiction. The display of graphic violence should arouse horror and distaste, and yet we find it aesthetically fascinating. At the same time, we know that it actually happened, which makes us feel guilty – almost immoral – for not taking it seriously.

The display of graphic violence should arouse horror and distaste, and yet we find it aesthetically fascinating.

This can't be real? Except that it is. Is it? Why can we only make sense of this reality through cinematic representations? The photo from Ankara exemplifies the blurring borders between the real and the imaginary. It looks theatrical, and yet the status of the medium guarantees its factuality. We look at it with uncertainty, skeptical of our own eyes.

Another aspect that triggers our incredulity is the reversed “roles” of the subjects depicted. The framing and composition place the killer in the center, thus conferring the spotlight on him. Anonymous, he becomes the “hero” of the picture, while the ambassador, a man with high status, lies defeated on the ground. We cannot empathize with the victim because he is unidentifiable and distant, nor can we condemn the perpetrator because he looks like a performer.

The dualist narrative of hero versus villain is thus disrupted. In other words, the photograph resists a straightforward, unequivocal moral reading of the viewer. It does not provide one single truth or a unique script, thus not dictating us how to feel.

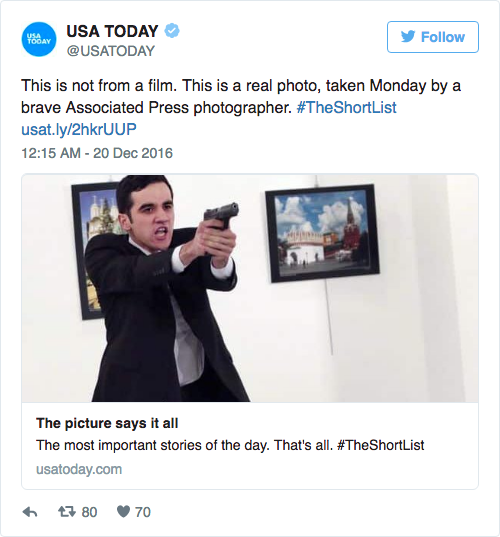

A tweet from USA Today featuring a similar picture from Burhan Özbilici

An engaging photo

Where does all this leave us? What can we draw from this mess, this confusion? The Ankara assassination photo misrepresents reality in the way that it obviously does not give us the truth, because of its aesthetic quality and its ambiguous meaning(s). Therefore, it puts us, even for a half-second, in doubt as to whether it is real. As said by the poet and critic Robert Archambeau, “The death is real. And the photos? They’re so good, they almost don’t let you see that.”

We need this moment of disbelief to distance ourselves from our image-saturated culture, in which continuous exposure to visual representations of violence and suffering has resulted in a compassion fatigue. We scroll through our news feed indifferently, immune to all kinds of horrors. And then comes this unsettling picture that catches our attention, simply because we cannot make sense of it. It engages us, ironically, because it seems to be fictional. In the end, the photo of the assassination in Turkey is less about what it shows than it is about what it says about us – the spectator. It refers to our own world and our relationship with images: fictional violence has become so real that it renders real violence surreal.

It engages us, ironically, because it seems to be fictional.

My point, however, is not to cast doubt on the power of photojournalism. As I mentioned above, it is less about what is looked at than about the one who looks. The conflicted reading of the Ankara photo reminds us to have a critical gaze and not to take a “shortcut” to reality. Today’s news revolves more and more around one single photo, but a photograph is also about what we do not see. As Susan Sontag wrote in one of her famous essays on photography: “There is the surface. Now think – or rather feel, intuit – what is beyond it, what the reality must be like if it looks this way.” This photo may be a misrepresentation of reality, but because of this, it can serve as an entrance point to a quest for deeper truth(s).