What is wrong with the Confucius Institute?

In this article, I investigate why the West is critically targeting the Confucius Institute. I will first analyze the Confucius Institute as a PRC (People's Republic of China) language policy institute, and then deal with Western criticism towards the Confucius Institute as a PRC institution. In doing so, I will try to reveal the pros and cons of this enterprise from actors' perspectives from both the PRC and the West.

Confucius Institutes under attack

Mainland China is the largest political unit that has ever existed, and its language and culture are an intrinsic part of that political achievement, one of the most amazing achievements of human culture (Hodge & Louie, 1998, p.1). Industrial products “made in China” and traded on a global scale have aroused people’s interest from around the world who want to know more about the success that lies behind the “made in China” brand (Zhao & Huang, 2010, p.128). Immediate access to the culture and people of China can be reached by way of the Chinese language.

The Beijing-based Office of the Chinese Language Council International – known as Hanban, a public institution affiliated with the Chinese Ministry of Education (MoE) – was established in 1987. Hanban is committed to providing Chinese language and culture teaching resources and services worldwide. It goes all out in meeting the demands of foreign Chinese learners and contributing to the development of multiculturalism and the building of a harmonious world (Hanban, 2018). To provide specific Chinese courses in each country, the Confucius Institutes (CIs) have been inaugurated. According to Hanban’s website:

As China's economy and exchanges with the world have seen rapid growth, there has also been a sharp increase in the world's demands for Chinese learning. Benefiting from the UK, France, Germany and Spain's experience in promoting their national languages, China began its own exploration through establishing non-profit public institutions which aim to promote Chinese language and culture in foreign countries in 2004: these were given the name the Confucius Institute.

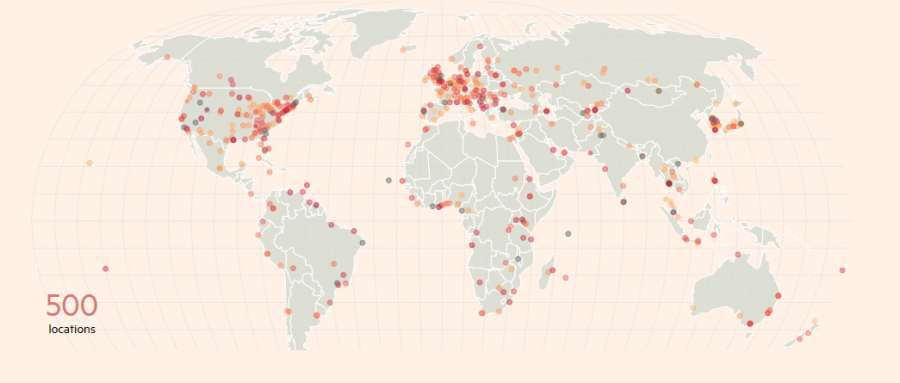

There are currently a total of 525 Confucius Institutes in countries around the world (Hanban, 2018). The headquarters — Hanban — oversees all the Confucius Institutes globally and continues to respond to the increasing demand for more. The promotion of Chinese language learning throughout the world is seen as part of China’s effort to accomplish its foreign policy goals through the use of soft power (Gil 2008, p. 116).

Figure 1: Confucius Institutes around the world (The Financial Times Limited 2017)

However, CIs have been criticized as propagating an idealized version of Chinese history and culture and stifling academic freedom. Recently, academics predicted a crackdown on CIs across the West. Especially in the US, where nearly 40 percent of CIs are located, members of the US Congress, the director of the FBI and academic advisory groups have gone so far as to accuse the Confucius Institute of being a "subversive" mechanism for increasing China’s public influence abroad.

The promotion of Chinese language learning throughout the world is seen as part of China’s effort to accomplish its foreign policy goals through the use of soft power.

In what follows, I will first analyze how Confucius Institute works as PRC’s language policy agency by looking at what it does, the actors involved, and its aims and means. After that, the criticism on CIs from the West will be studied. I conclude with a summary in pros and cons of this language policy institute. Given the fact that CIs are located around the globe, the method of analysis follows a discourse analysis of data collected online such as published data, official documents, and news reports.

The Confucius Institute as a language policy agency

When we see language as a policy object, as in language policy and planning, scholars distinguish three different forms: status planning, corpus planning and acquisition planning (Cooper, 1989). According to Hornberger (2006), status planning refers to efforts directed toward the allocation of functions of languages/literacies in a given speech community, corpus planning focuses on the adequacy of the form of languages/literacies, and acquisition planning is directed towards creating opportunities and incentives for learners to acquire additional languages/literacies. According to Hanban, the Confucius Institute is comparable to Germany’s Goethe Institute or Britain’s British Council at the level of status planning, in order to promote Chinese language and Chinese culture around the world.

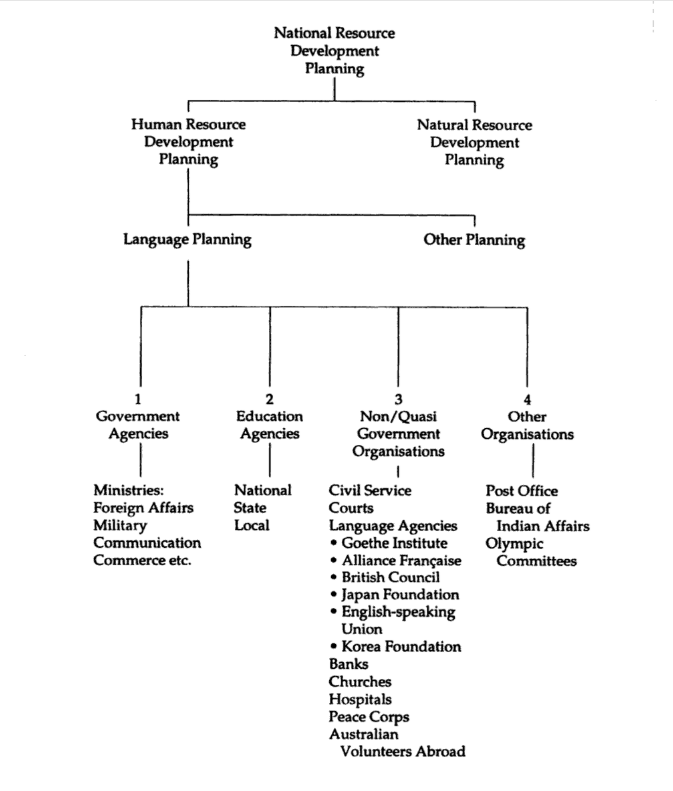

Kaplan & Baldauf (1997, p. 5) demonstrate that in the late twentieth century most governments became involved in the language planning business, either because they wanted to or because they stumbled into it. Figure 2 shows language planning in context, i.e. in a range of governmental agencies that are involved. Confucius Institute is governmental and not independent from the Chinese government, yet Goethe Institute and British Council are in the figure under Non/Quasi-governmental organizations. In this sense, Confucius Institute cannot be comparable to neither the Goethe Institute nor the British Council, despite what Hanban has assumed.

In the context of the Chinese government promoting Chinese language learning, the MoE is the government education agency. As a policy maker it receives the reports from Hanban. Hanban is the language agency of the MoE. As the headquarters of the CI, together with all the CIs around the globe, they are the policy implementers. The target groups are universities or colleges in foreign countries. There are also Confucius Classrooms, which are set in primary and secondary schools all over the world.

Figure 2: Language planning in context (Kaplan & Baldauf, 1997, p. 6)

Politics steer policy. Confucius Institute is a top-down approach to language planning, in which CIs around the world are designed, financed, and implemented by the Chinese government. The role of Hanban according to Hanban’s website is as follows:

1) A Confucius Institute is normally attached to an overseas university, there will be a similar university in China as the partner. The overseas university works with a Chinese partner university to put forward a proposal for a Confucius Institute to the headquarters of CI in Beijing, which is administered by Hanban. With the approval from the headquarters of CI, the headquarters at Hanban sign a standard contract with the overseas university. The university receives Confucius Institute funding for start-up financial support.

2) Hanban organized to compile and developed the international standards for Chinese language teachers. This action aims at the target of training a mass of qualified Chinese language teachers to satisfy the ever-growing demand for Chinese language learning in other countries.

3) Government-sponsored teacher programs are also among the most important strategies. MoE and Hanban have decided to send Chinese language teaching advisors and teachers to the ministries of education, universities, high and primary schools in other countries, and the organizer shall be Hanban.

4) Although the majority of CIs are tied to universities, Hanban also promotes CIs with schools that supply Chinese language programmes particularly aimed towards younger people.

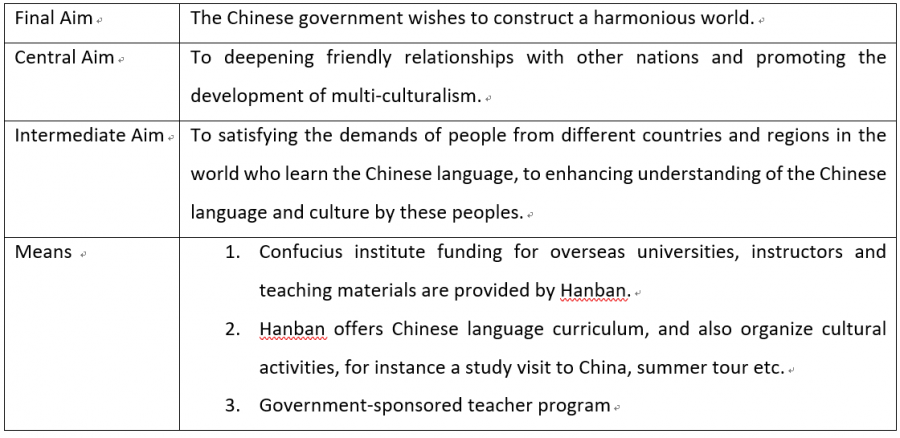

The table below (Figure 3) presents the results of my analysis of the aims and means according to the Constitution and By-Laws of the Confucius Institute. It briefly summarizes what aims Confucius Institute as a national language policy agency tries to achieve and what actions Hanban as headquarters of CI takes to achieve the aims.

Figure 3: Aims and means table of Confucius Institute as a national language policy

After having analyzed the Confucius Institute as a language policy agency, I will now analyze how the changing ideology of the West affects their ideas on the Confucius Institute, i.e. the language policy formulated by the Chinese government.

Criticism from the West

The Constitution and By-Laws of the Confucius Institutes list their services that shall be provided to local CIs as follows:

1. Chinese language teaching;

2. Training Chinese language instructors and providing Chinese language teaching resources;

3. Holding the HSK examination (Chinese Proficiency Test) and tests for the Certification of the Chinese Language Teachers;

4. Providing information and consultative services concerning China's education, culture, and so forth;

5. Conducting language and cultural exchange activities between China and other countries.

These services have attracted many universities overseas to establish a CI. To meet the high level of demand to learn Mandarin Chinese, with Hanban paying not only for the institutes’ operational costs and selected textbooks, but also providing trained Chinese language teachers, the universities can benefit from the financial support to offer Chinese program for students almost for free. Almost all CIs are primarily committed to carrying out the policy of providing Chinese language teaching and introducing Chinese culture, teacher training, and Chinese language learning resources. For instance, the Confucius Institute at Leiden University (CILU, 2006) shows Hanban’s mission on its website:

The Confucius Institute is an international, non-profit organization for the advancement of knowledge and understanding about Chinese language and culture around the world. Through a variety of teaching methods and activities we aim to enhance understanding of Chinese culture.

However, =criticism occurs about PRC footing the bill and directly managing the teachers. Critics say CIs are ready-made platforms for the state’s agenda, promoting an overly rosy image of PRC while discouraging discussion of politics (Zhao & Huang, 2010). According to a friend of mine who is teaching Mandarin at a Confucius Institute in the US, teachers are told not to discuss politics with students, and they are possibly under censorship. Critics also say the CI teachers are not employed by the host universities and are therefore not protected by codes of academic freedom.

Confucius Institutes are ready-made platforms for the state’s agenda, promoting an overly rosy image of PRC while discouraging discussion of politics.

After a period in which the West was eager to establish CIs, which can be considered an act of language policy, more concretely giving a specific status to Chinese as a foreign language, contemporary criticism can be seen as a new phase of ideology formation with the intent to arrive at a somewhat different language policy, i.e. a language policy that does not allow pro-China propaganda to be spread via Chinese language and culture teaching by CIs. The anti-CI position occurred as a consequence of changing ideologies in the West regarding China becoming a main global player, thereby confirming Ricento's (2006) statement that “ideologies about language in general have real effects on language policies and practices, and delimit to a large extent what is and is not possible in the realm of language planning and policy making.” There are three main issues regarding these changing ideologies in the West.

First, as analyzed above, China utilizes CI as a language policy agency to promote Chinese language and culture. The ideology behind this language policy has shifted towards a ‘cultural tool’ of China’s global influence as Kurlantzik (2007) indicates. There is little doubt that China sees the promotion of Chinese language learning as one of its soft power tools (Gil, 2008), as shown in a statement made by a National People’s Congress (NPC) deputy, Hu Youqing:

Promoting the use of the Chinese language will contribute to spreading Chinese culture and increasing China’s global influence. It can help build up our national strength and should be taken as a way to develop our country’s soft power (quoted in Kurlantzick, 2007, p. 67).

The Confucius Institute as China’s soft power tool mainly depends on its economic and political prominence. “China’s glowing economy might allow Beijing to deploy the tools [of culture], since of course it costs money to hold cultural summits or send language teachers to other nations” (Kurlantzick, 2007, p. 61). When arriving at intense criticism, "greater transparency is essential," said CSIS (Center for Strategic & International Studies). "China has had limited success at promoting its soft power around the world. Positive attitudes toward China appear to be in large part a result of its economic largesse” (quoted in Rahn, 2018).

Second, Western Universities co-produce this policy by applying for CIs and making Chinese language available to students. According to Hanban, there are certain basic requirements foreign partner universities should meet before they apply for a CI: (1) that there is a demand for learning the Chinese language and culture at the applicant's location; (2) that the personnel, space, facilities, and equipment required for language and culture instruction are available; (3) that the capital for the establishment is in place, and that the source of funds for operation is stable. Besides, Hanban also requires that the applicant should “get to know the Confucius Institute's nature, mission and business service.” It seems Hanban is critical in allowing CIs to be set in foreign partner universities. Those who do not agree with CI’s nature, mission and business service will experience failure in applying for a CI.

Third, the ideology from China’s side stays the same but the Western ideology changes. Hanban is dedicated to providing all the teaching resources with an aim that all the CIs would be operating in thesame way. But not surprisingly, this is not going to work in the West, because the Western core value of freedom - the freedom to question and challenge - does not allow propaganda to be spread in class. The West also criticizes China’s unique political system and issues like human rights, etc. Therefore Western universities intend to govern or limit CIs. This is leading to an anti-CI position regarding CIs as instruments of the Chinese government.

Confucius Institutes operate differently around the world, so it is difficult to generalize.

The term ‘governance’, according to Richards & Smith (2002), it is a descriptive label that is used to highlight the changing nature of the policy process in recent decades. In particular, it sensitizes us to the ever-increasing variety of terrains and actors involved in the making of public policy. Thus, it demands that we consider all the actors and locations beyond the ‘core executive’ involved in the policy making process (ibid, p.2). With the changing nature of the policy process, the core executive is often challenged. Here we refer to Hanban, which receives dynamic reactions from partner institutes overseas. Hanban oversees all the CIs globally, critics view the Confucius Institutes as mostly a vehicle for propaganda under such governance by the Chinese government.

However, CSIS suggests that “Confucius Institutes operate differently around the world, so it is difficult to generalize.” Rathn (2018) reports each Confucius Institute has a different mission and governance structure and there are universities in the US that value the Confucius Institute's role in meeting a public demand for access to Chinese culture and language. For instance, the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) states that its Confucius Institute performs a valuable public service, and operates under an agreement corresponding to the university's academic principles (ibid).

The pros and cons of Confucius Institute

There is a need for the world to know about China and the Confucius Institute as a language institute is based on the agreement that both parties have on language, culture, exchanges, etc. The promotion of Chinese language learning by Confucius Institute has been successful in creating a positive image of Chinese and attracting learners. It cannot be neglected that CIs are providing great resources for people who want to learn Chinese language and culture around the globe.

Applying for Confucius Institutes used to be seen as an act of language policy of the West to give status to Chinese as a foreign language. However, the changing ideology across the West affects how they see the Confucius Institute as a language policy agency and they thus call for greater transparency within CIs. The ideology behind the criticism is the different value systems between China and the West. The West insists that the values of free expression, speech and debate should not be suppressed, and thus do not allow pro-China propaganda to spread. This suggests the host universities have more autonomy in CIs, and the teaching and faculty should meet the code of academic freedom.

The Chinese Ministry of Education, should allow more transparency and autonomy in each Confucius Institute.

A balance should be achieved between the purpose of the policy and implementation measures, to reduce the tension between the actors. The policy maker, the Chinese Ministry of Education, should allow more transparency and autonomy in each Confucius Institute. Because it is impossible to govern them all due to changing nature of the policy process, especially in the West where the freedom of speech, expression, and debate are highly valued. This requires more mutual understanding and respect.

References

Cooper, R. L. (1989). Language planning and social change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gil, J. (2008). The promotion of Chinese language learning and China’s soft power. Asian Social Science, 4/10, 116–122.

Hanban (2018). Confucius Institutes Headquarters. Retrieved on 7 May 2018: http://english.hanban.org/node_7716.htm

Hodge, B., & Louie, K. (1998). The politics of Chinese language and culture, the art of reading dragons. London: Routledge.

Hornberger, N. (2006). Frameworks and models in language policy and planning. In T. Ricento (Ed.), An Introduction to Language Policy: Theory and Method (pp. 24-41).London: Blackwell Publishing

Kaplan, R.B. & Baldauf, R. B. (1997). Language Planning from Practice to Theory. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Kurlantzick, J. (2007). Charm offensive: how China’s soft power is transforming the world. New Heaven, CT: Yale University Press.

Rahn, W. (2018). Why is the US targeting China’s Confucius Institute? Deutsche Welle. Retrieved on 7 May 2018: www.dw.com/en/why-is-the-us-targeting-chinas-confucius-institute/a-43403188

Ricento, T (2006). Theoretical Perspectives in Language Policy: An Overview. In Ricento, T. (Ed). An Introduction to Language Policy: Theory and Method (pp. 3-9). London: Blackwell Publishing.

Richards, D. & Smith, M. (2002). Governance and Public Policy in the United Kingdom. Oxford: Oxford University press.

Zhao, H. & Huang, J. (2010). China’s policy of Chinese as a foreign language and the use of overseas Confucius Institutes. Education Research for Policy and Prac tice (2010) 9: 127-142.