Freedom, Authenticity, and Traveling

On Instagram, everybody seems to be a traveler, longing to be free and finding that 'authentic' place or 'experience'. Traveling and backpacking should be on everyone's bucketlist: it is the new normal.

Travelers in the digital age

Scrolling down my Instagram, I am always surprised about the number of people who are traveling these days. Quotes like ‘please take me back’, and ‘most amazing experience of my life’ make you think that all these people had a really special and authentic experience. But whereas backpacking once was a method of traveling only practiced by counterculture hippies from the late 20th century, it now is totally mainstreamed (Paris, 2010).

In the Netherlands, almost two out of every three people in their twenties expect to make a long journey. What was an exception ten years ago is now the standard, if it is not the minimum expectation for the average twenty something. What caused this enormous increase of in backpacking all over the world? What are the consequences of this movement? And how freeing is this kind of traveling, if all those people do practically the same thing?

Quotes like ‘please take me back’, and ‘most amazing experience of my life’, make you think that all these people had a really special and authentic experience.

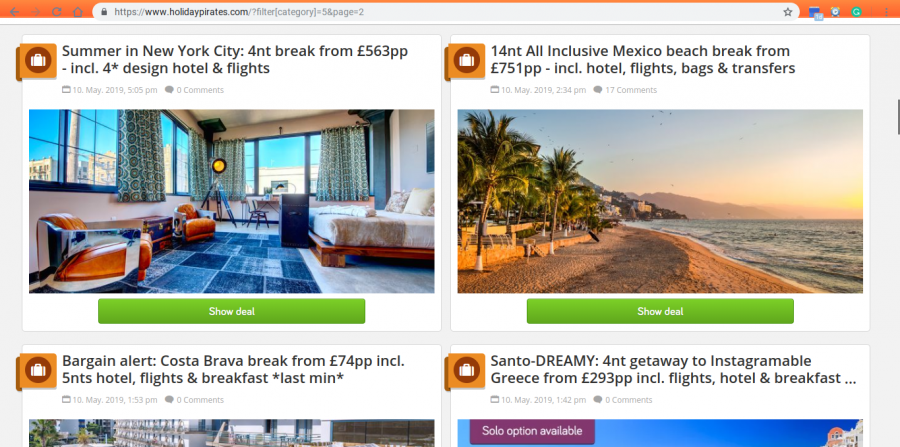

Traveling has become more accessible than ever before. Cheap international flights make it very easy to travel. A €400 return ticket to Bangkok is now a normal price. Different travel websites compete each other, combining low prices with beautiful pictures. Besides that, the increasing internal flight possibilities provide more comfortable opportunities than spending days on a bus. Especially in South-East Asia, domestic flight prices are ridiculously low and sometimes even cheaper than going by bus.

Cheap holidays

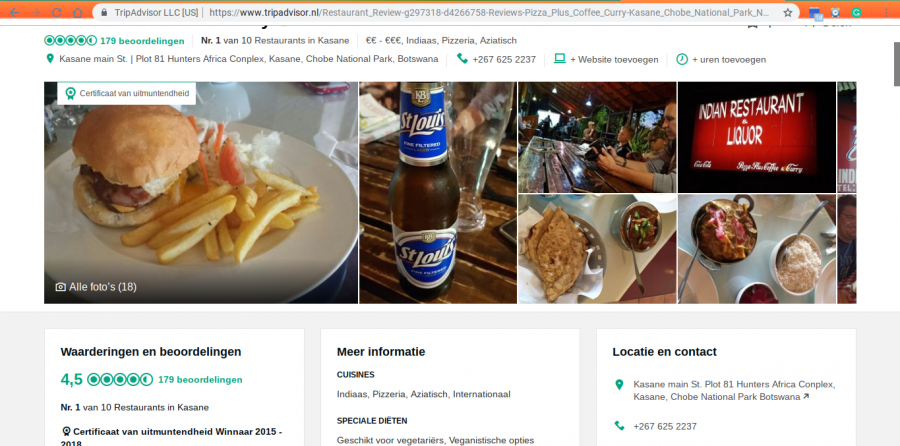

In addition to the cheap transfers, technological developments make traveling much easier. Whereas gathering information for planning a journey was once only possible by books, these days everything is online. From a top 10 of the best hotels in Tadzjikistan to a picture of the exact burger you will receive on your plate in an Italian/Indian restaurant in Botswana, the internet leaves travelers with no surprises and the ability to plan their whole trip, all small details included.

Online social networks

Technological developments not only caused an increase in information gathering by travelers, but they also make use of the web 2.0. People share experiences and are part of communities using technology: ‘New innovations in communication technologies including Web 2.0, Mobile phones, laptop, and netbook computers, and Wi-Fi access have created hybrid-spaces for backpacking, blurring boundaries between the physical and virtual, as well as the virtual and cultural’ (Paris, 2010).

All of this results in the fact that traveling to the other side of the world is not that impactful as it was before. The travel experience has been completely reshaped by new communication practices that have changed the meaning of distance (Mascheroni, 2007).

The travel experience has been completely reshaped by new communication practices that have changed the meaning of distance.

When leaving our physical environment, we no longer leave our social networks. Together with worldwide information, we take our social lives with us when we take our mobile phone. Through social media, we are continuously connected with our entire network system. Even though we hear statements like ‘escaping society’ or ‘leave everything behind’all the time, they are no longer suitable.

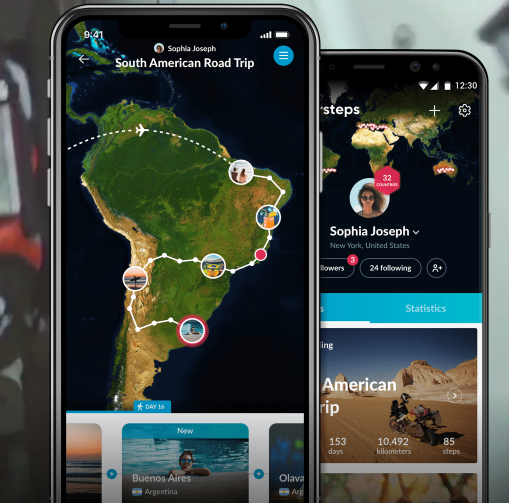

In all the social networks atraveler is part of, the distance between participants of those networks is minimal, even while being thousands of miles away (Castells, 2012). It is very common that a traveler is even more visible in the network than while staying at home. By using specially designed applications to follow you by foot, travelers are able to keep their networks updated. These applications show exactly where you are and have been, and gives the opportunity to add pictures and stories. An example of this is the application Polarsteps, as shown in the image below. This application provides a travelers' network with all kind of information the people in the network probably wouldn't care less about in an ‘at home’ life.

Statements like ‘escaping society’ or ‘leave everything behind’, even though heard all the time, are no longer suitable.

Polarsteps

Traveling as identity creation

The reduced prices and the possibilities created by technological development are obviously factors contributing to the increasing group of young people’s traveling all over the world. All this said, accessible circumstances are not the main motivation for traveling. As mentioned before, an enormous amount of people in their twenties is traveling these days. It became part of their perceived ‘development’. Who are you if you have not been to the other side of the world? What can you say if you have not been overseas?

Ask google ‘why traveling’ and it provides you entire lists of ‘17 reasons why around the world travel is good for you’ and ‘6 reasons why traveling abroad is important for young people’. People even write complete confessions about why they do not want to travel. They apparently are the ‘strange’ outgroup minority. According to these websites, through traveling people develop themselves and their identity. Traveling has become a practice for identity creation, an aspect that is increasingly important in the context of superdiversity: the extraordinary complexity of social configurations also caused by the digital revolution (Blommaert & Varis, 2011).

People even write complete confessions about why they do not want to travel. They apparently are the ‘strange’ outgroup minority.

The identity creation of traveling alsoevolves in virtual contexts (Blommaert & Varis, 2011). Traveling is an identity practice, a way to identify yourself and others. While traveling in the 1960s, travelers just had one hippie identity. Today, ones ‘individual life project’ óf identity formation contains different ‘micro-hegemonies’: different niches of social spheres. People are part of different identity groups in all different ways (Blommaert & Varis, 2011). This is fed by the use of modern technology that provides information about these micro-hegemonies. The traveler is not changing his or her identity, but only is more active in the particular micro-hegemony of ‘traveler’. Meanwhile, they also orient other parts of their lives to other centers of micro-hegemonies.

Blommaert & Varis (2011) have made a framework to describe such identity practices. The identity discourses and practices are the practical features travelers use to express their identity. These practices are for examplespiritual interests, the ‘free your mind’ attitude, the shithead card game, being stingy, getting a tattoo and posting beautiful pictures of ‘authentic’ places. These practices are not just ‘random’, but always contain an ‘essential combination’ to make sure that they provide the traveler with ‘authenticity’.

Besides the interaction among travelers, the internet is a way to provide people with information on how to do this. The possibility to share your travel experiences online is a means to confirm your belonging to the backpacker community and to maintain the backpacker identity formation (Mascheroni, 2007). Furthermore, the internet is used to participate in online forums. These online interactions are symbolized by the gift and reciprocity economy which is typical for the backpacking culture. In this way, participation in these forums is also a form of maintaining the backpackers' identity, even while at home.

These practices are for example spiritual interests, the ‘free your mind’ attitude, the ‘shithead’ card game, being stingy, getting a tattoo and posting beautiful pictures of ‘authentic’ places.

To give an example, I experienced a problem myself while backpacking last year. My friend and I did not know what to do while being robbed, so we asked help on an online backpackers forum. Another member of the group helped us out by answering my question in a very extensive way (about 300 words). For answering this extensive, the member received 32 likes and loves of other members. The amount of likes shows the appreciation of this group. The person's position is strengthened and other members know what is appreciated. Of course, goodwill is probably the main motivation to help people the way this woman helped us. Yet, the openness of the forum and the likes make it a practice to confirm identity, an identity practice.

Cultural scripts

All these identity practices from different micro-hegemonies together partially form a person's behavior. What looks like a spontaneous picture or post on the internet, a simple game, or an honest interest contains a whole cultural script to establish one's identity. The rules of these scripts are created and spread by the ‘experts’. These experts are the most liked, most unique and most followed people who visit all the unique places.

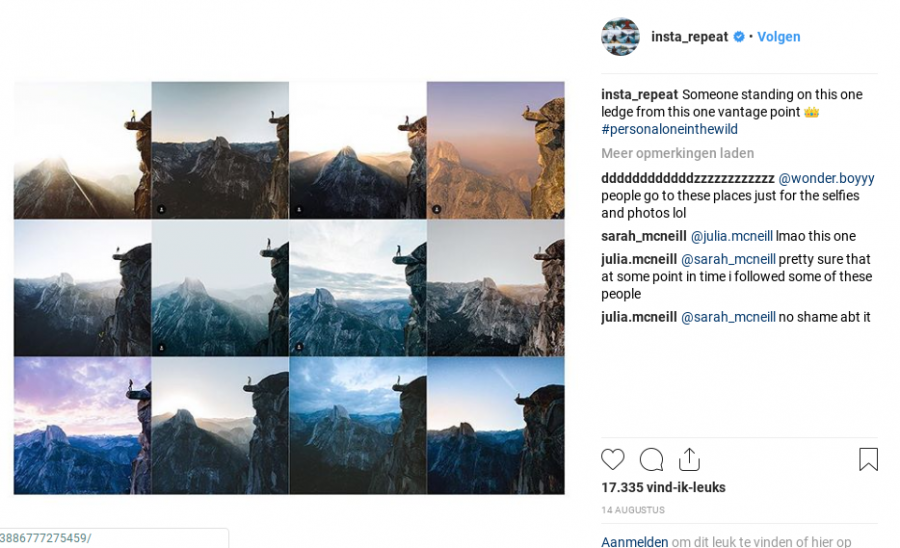

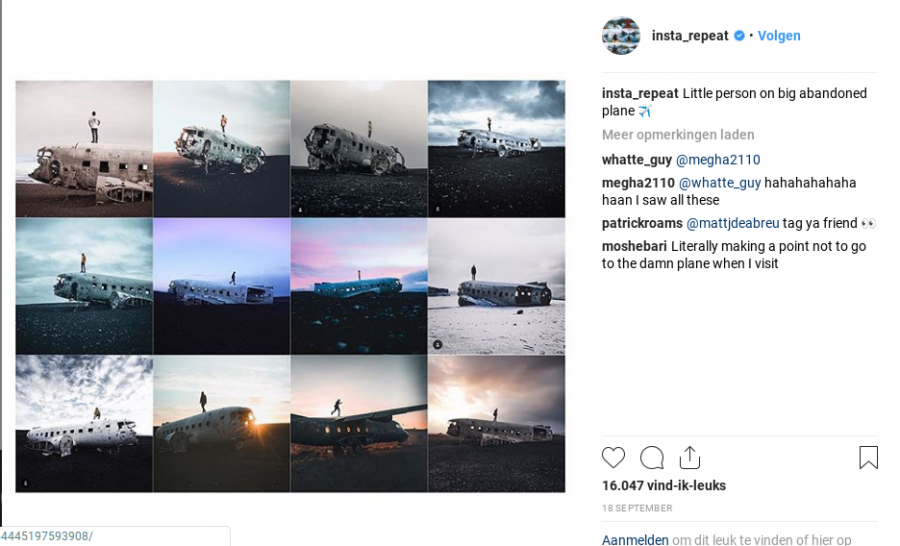

An example of these ‘experts’ are travel influencers, who tell the ‘learners/followers’ where to travel, how to look and how to make pictures to be an ‘authentic’ member of the travel identity category. But of course, the fact that people all follow the same ‘leaders’ results in less authentic outcomes. For example, by posting pictures of the visited destinations, people show the world their ‘authentic’ experiences. Atfirst glance the pictures look authentic, but as visible on the Instagram pages below, they are anything but. This Instagram collects travel pictures of different people who make almost the exact same picture.

'Unique' pictures

'Unique' pictures

'Unique' pictures

This following behavior is the same as what has happened with travel destinations. The ‘leaders’ of the travel micro-hegemonies are so influential, they influence others to the point of ruining destinations. Take for example the Figure Eight Pools in Australia. A few years ago, this was a little known natural pool. But once this place was discovered by a few famous Instagrammers, the place became unbelievably popular (Hutchinson, 2018). It became even so popular that, when you take a look at the national park website now, they warn you not to come:

‘Pick a better spot for a selfie. Instead of breaking a limb at Figure Eight Pools, take photos at some other beautiful places. Avoid the crowds that Figure Eight Pools is now infamous for.’ (NSW National Parks, n.d.)

Authenticity marketing

Besides ruining existing places, completely new ‘authentic’ places and rituals have arisen. MacCannell described this phenomenon as 'staged authenticity' (1973), which refers to the creation of authentic local culture impressions for tourists. Tourists want to investigate and enter back regions because of the association with the intimacy of relations and authenticity of experiences. To fulfill this need, tourist settings are arranged to produce the impression that a back region has been entered (MacCannel, 1973). If this is true or not is not relevant anymore since it is only about the experience.

Take for example the place Shangri-La in China. After James Hilton wrote in 1933 about this mysterious place, people became interested in visiting it. It should be an authentic, Tibetan place with no outside influences. There was only one little problem: it did not exist. Meanwhile the town of Zhongdian was having economic problems, and came up with the idea to create and become this magical place. The old Zhongdian was destroyed and a new Shangri-La was built in 2001, with big marketing campaigns. After a fire in 2014 destroyed the ‘old town’ (only 13 years old), the authorities choose to reconstruct the brand new Shangri-La in an authentic Chinese look, and Shangri-La became a fake ‘authentic ancient town’, like many others in China (Smart Trip Platform, 2018). Over 17 years, Zhongdian had changed from an authentic city to two different fake 'authentic' cities.

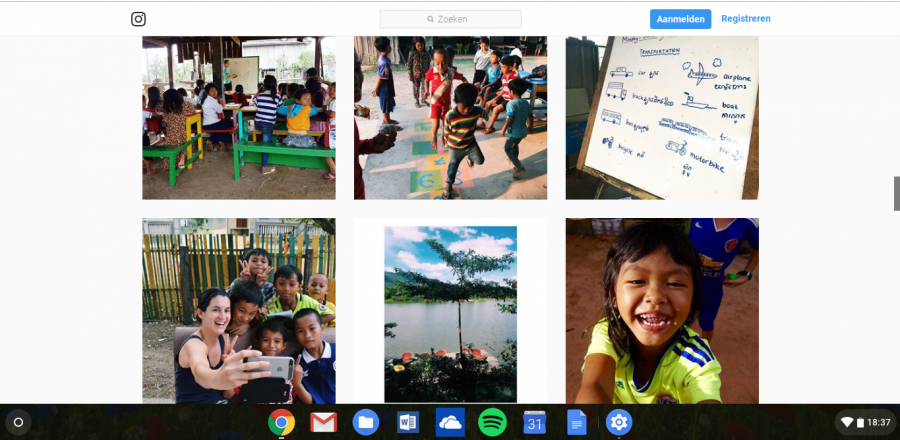

Apart from creating new destinations for experiencing 'authentic' moments, the market mechanism ofauthenticity reacts to this demand by creating fake experiences in a more harmful way than simply building new towns. Take the example of orphanages in Cambodia: volunteering is seen as an 'authentic' experience to truly get to know a culture. Searching Instagram for #volunteeringcambodia gives you the following results.

#volunteeringcambodia

Websites of highly profitable volunteer organizations advertise with quotes like ‘authentic experiences’ and ‘help make a difference’. It will leave you with the idea that there could not be anything wrong with this peacful activity. But in fact, by volunteering at these orphanages people create new ‘fake orphanages’. UNICEF reported that only 28% of the orphanages' children in Cambodia are in fact orphans, and that the number of orphanages is rising while the number of orphans is decreasing.

The reason for these ‘fake orphanages’ is the demand-supply gap in the market mechanism of volunteering, which is fixed by creating fake orphans just for making money. Families from poor rural areas are manipulated into sending their children to an orphanages to take advantage of the plethora of well meaning western volunteers (Vargas, 2017).

The world has become an Ikea of experiences to buy.

Buying authenticity

Authenticity in traveling has become a common good that everyone is looking for. The world has become an Ikea of experiences to buy. Commodities like staying at a specific hostel or a trip through the jungle are packaged as cultural objects, asa life improving experience. These commodities are promoted by the ‘experts’ and ‘leaders’ of the identity group. They promote that by buying these commodities, you buy a bit of the identity.

What can be concluded is that the perceived freedom of a lot of travelers is a myth, and that the ‘authentic’ experiences are mostly fake as well. Every place is already visited by tourists and influenced by them. It seems that to come home with an 'authentic' story, you have to, at least, almost died, been lost and found by a local, and spend a night at a hospital. So what are the next steps in this search for authentic travel experiences? Are people intentionally getting lost in dangerous jungles? Is dark tourism expanding to current war places for experiencing authentic and original experiences? And do countries react to this movement by starting fake civil wars then?

References

Appadurai, A. (1990). Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy. Theory, Culture & Society, 7(2-3), 295-310. doi:10.1177/026327690007002017

Blommaert, J., & Varis, P. (2013). Enough is enough. The heurisics of authenticity in superdiversity. InJ. Duarte & I. Gogolin (eds.), Linguistic Superdiversity in Urban Areas (pp. 143-160). Hamburg Studies on Linguistic Diversity 2. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Bom, S. (2017). 'Als je geen verre reis maakt, is je leven niet compleet.'

Groundwater, B. (2017). Why backpackers aren't fun anymore.

Hutchinson, A. (2018). Instagram Is Ruining Some of Australia's Most Photogenic Locales.

MacCannell, D. (1973). Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. American Journal of Sociology,79(3), 589-603.

Mascheroni, G. M. (2007). Global Nomads' Network and Mobile Sociality: Exploring New Media Uses on the Move. Information, Communication & Society, 10(4), 527-546. doi:10.1080/13691180701560077

Mdgadvertising.com. (n.d.). How millennials killed travel marketing as we know it [PDG].

NSW National Parks. (n.d.). NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service | Home | NSW National Parks.

Paris, C. M. (2010). Understanding the Virtualization of Backpacker Culture and the Emerge of the Flashpacker: A Mixed-Method Approach. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, 25-35. doi:10.1007/978-3-211-93971-0_3

Smart Trip Platform. (2018). The sad truth about Shangri-La ? is it really worth going?

Vargas, N. (2017). How Orphanages in Cambodia Trick Travelers.