Debating Tilburg's 'beautiful ugliness' online: The case of The Blue Building

Despite the popular use of the saying “there is no arguing about matters of taste”, in the Dutch city of Tilburg, ‘taste’ is a topic that is regularly at the center of heated debates. As a city that is regarded as ‘ugly’ by many of its inhabitants and by a significant part of the population of the Netherlands, the city appears to be in constant flux to deal with its own ugliness. The local university newspaper even wrote an article to explain why the city is so unsightly (Wassens, 2013). By considering Tilburg’s constant quest to find an attitude towards its own appearance as an outstanding collaborative sociocultural balancing act, this article engages with the digital discussion about The blue building to demonstrate how responses to the building's demolition connect with one of Tilburg's most exceptional identities: the city’s celebrated ‘beautiful ugliness’.

The birth of 'The blue building'

In May 2017, some inhabitants of the Dutch city of Tilburg noted that the former office building of the local social service had never received an official name (van der Schaaf, 2017b). One of them, Tom Pijnenburg, launched an initiative to fix this deficiency (Pijnenburg, 2017); calling his fellow citizens to submit names for the building that was, at the time, known as Tilburg’s “ugliest building”. Dozens of potential names were proposed, and journalists and prominent ‘Tilburgers’ became involved (Beversluis, 2017). Some people suggested to just call the building “ugly”, or to adopt a name that reflects its proximity to the railway station. Eventually, the building was unofficially named “The blue building” — "Het blauwe gebouw" in Dutch — because of the blue tiles that were used in its lower part.

These pictures show the building on Besterdring 235 in Tilburg in the spring of 2022.

Though the owner of the building and local government officials had been conversing about its future since the social service vacated it in 2014, the first decision regarding its potential demolition was only taken in December 2017. Anticipating this decision, Pijnenburg and his associates transformed their informal “working group” into a formal “pressure group”. They recruited new members — including a national heritage organization and Tilburg's local political party (van der Schaaf, 2017a) —, got more journalists involved, organized guided visits (BN DeStem, 2017; van Dael, 2017), started a petition and arranged research into the building’s heritage values (de Gram, 2017; Koningsberger, 2017). Despite these efforts — which reflect different modes of heritage activism (Moshenska, 2020) —, the local government decided The blue building would not become a protected monument in June 2020 (Pijnenburg, 2020) and the highest judiciary institution of the Netherlands ruled it could be demolished (Raad van State, 2020).

Whilst some people continued to discuss their love for The blue building and alternative plans for its future (van den Dries, 2021; De Erfgoedstem, 2021), it was generally accepted that the building’s demolition would start mid 2022 (Hest, 2020; Godefroy, 2021). Eventually, a demolition company started to dismantle the building at the end of that year (van der Vliet, 2022). An apartment block containing 150 homes will be constructed in its location (van Hest, 2020).

Ugliness as an identity marker

After The blue building was finished in 1977, it became a national subject of controversy (Brabants Dagblad, 2017; Wiki Midden-Brabant, 2021). Inhabitants of Tilburg felt it was hideous and argued it was improper to utilize such an eye-catching building to grant unemployment benefits (van der Vliet, 2017). Others thought the building was beautiful. National architecture magazines praised architect Jac. van Oers for the materials he had used and the building’s angled shapes (Koningsberger, 2017; Erfgoedvereniging Heemschut, 2018).

“Tilburg? That’s love at second sight”

During the last decades, The blue building was incorporated into shared narratives of “beautiful ugliness” (Vermeer, 2020) and “expressed ugliness” (Dutchtowns, n.d.). Tilburgers created suitably ugly songs about the city’s drabness (van Boesschoten, 2011) and the historic expression “Tilburg? That’s love at second sight” (van de Donk, 2017) became widely used, even on national television. The city won a regional competition regarding ugly buildings (Omroep Brabant, 2019) and social media accounts like KeepTilburgUgly were created to celebrate the city's ugliness.

This screenshot shows six previews of Instagram posts that were made by KeepTilburgUgly. The building at the top in the center is The blue building.

Together, texts describing Tilburg as “beautiful in ugliness” are now considered the grand “hymn” of a significant section of the city’s population (Vermeer, 2018).

Demolition as a local tradition

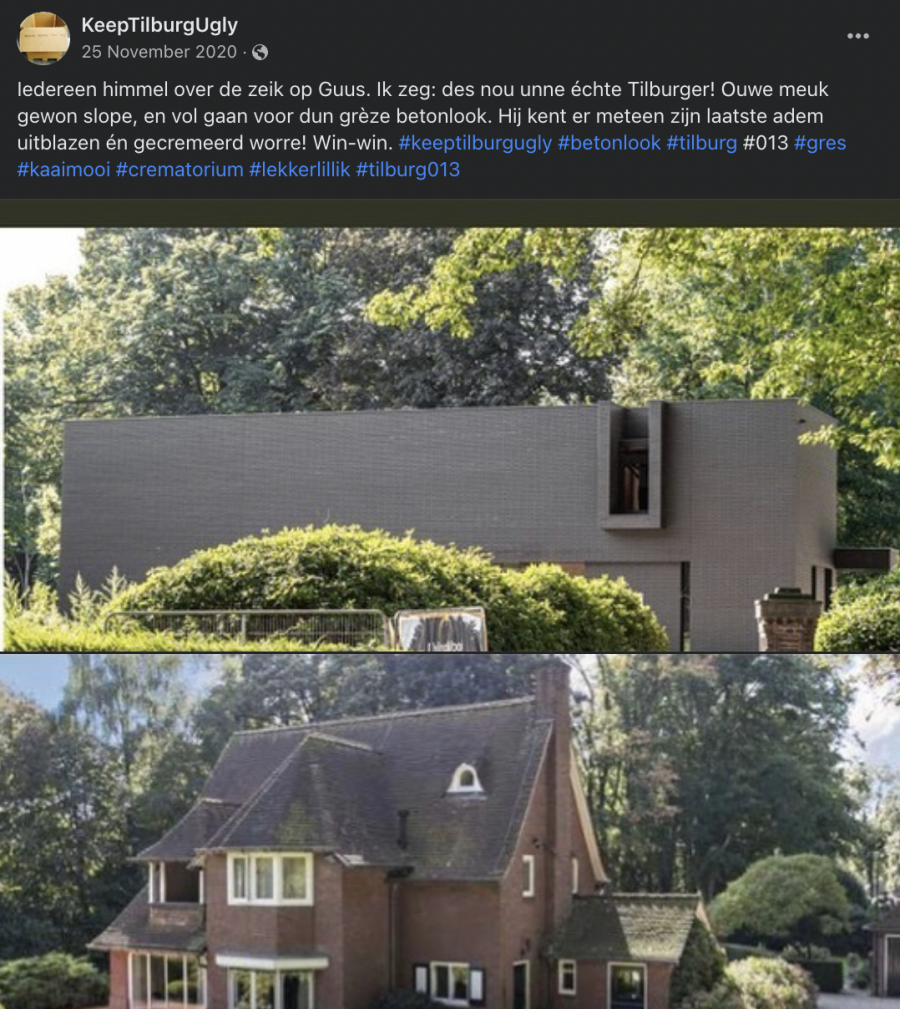

In Tilburg, there is a clear connection between ugliness and demolition, as can, for instance, be seen in a Facebook post of KeepTilburgUgly.

This screenshot shows a Facebook post by KeepTilburgUgly about Guus Meeuwis' new house.

The Facebook post of KeepTilburgUgly engages with a ‘beautiful’ building — the picture below — that was demolished in order to build an ‘ugly’ building — the top picture — by Guus Meeuwis, a famous Dutch singer and longtime inhabitant of the city. The text argues: “Everyone totally pissed off at Guus. I say: that’s a real Tilburger! Just demolishing old junk, and totally going for the gray concrete look. There, he can breathe his last breath and be cremated directly! Win-win. #keeptilburgugly #concretelook #tilburg #013 #grey #verybeautiful #crematorium #nicelyugly #tilburg013".

“Everyone totally pissed off at Guus. I say: that’s a real Tilburger! Just demolishing old junk, and totally going for the gray concrete look."

According to the post, famous singer Guus Meeuwis has demonstrated he is a “real Tilburger” by demolishing a beautiful building to make room for an ugly building. The humorous characterization refers to the mayorship of Cees Becht between 1957 and 1975. The mayor, who is known as “Cees the Demolisher” ordered the demolition of dozens of ‘beautiful’ buildings in order to transform Tilburg into a modern city (Beekmans, 2019).

This fragment of a newspaper article that was published in honor of Becht’s retirement identifies the mayor as “Demolisher Becht''.

Though particularly young Tilburgers now propagate this ironic ‘demolisher’-identity, some older Tilburgers remember the 60s and 70s as a traumatic period. They feel they were forced to watch helplessly as their city was violently destroyed. In discussions regarding The blue building, this trauma is often mentioned; either because people want to erase all traces of the 60s and 70s — a motivation that is also observed in research regarding heritage and stigmatized spaces (Moses, 2015) —, or because people want to avoid a new similar trauma, which is why they are against demolition in general (Geerts, 2018) — a motivation that can be linked to the general emergence of heritage conservation (Oliver, 2016).

Acting ugly on Facebook

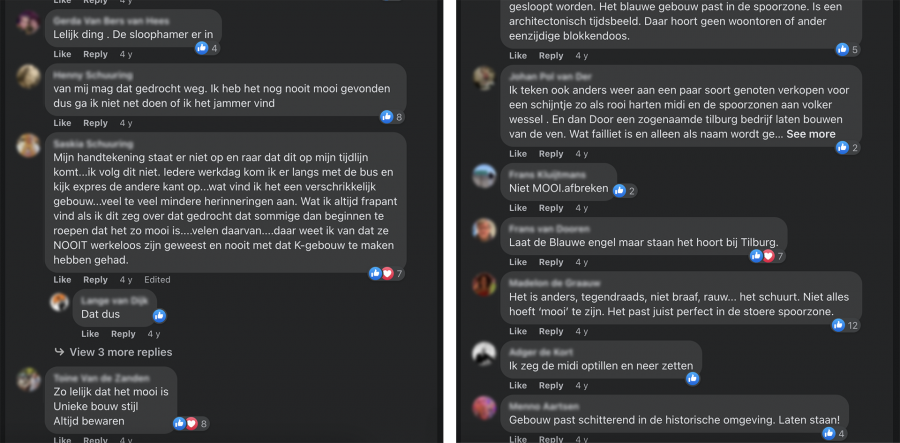

Even on the Facebook page of the pressure group that attempted to save the building, opinions regarding The blue building are heavily divided. An analysis of one of the most popular posts of the page — it received 70 comments and was shared 48 times — reveals the practical articulation of the various, historically constructed approaches towards demolition and ugliness in Tilburg.

These screenshots show some comments that were posted in response to a Facebook post of The blue building.

The gross of the respondents simply note the building is repulsive, and argue it should be torn down. Some are even annoyed by the pressure group’s attempts to save it, and note, for instance: “if you think it’s so pretty, you should just buy it yourself and go live there from your own money”. Other comments connect The blue building to different, partially conflicting perspectives on the history of the city and ‘De Spoorzone’ — the neighborhood of the building; which used to be a secluded area that contained the workshops of the national railroads, but is now one of the ‘cool’ parts of the city because of its old industrial buildings, high quality restaurants, cultural activities and modern apartment buildings. One person, for example, argues that “this has nothing to do with history and Spoorzone”, while someone else refers to the idea of “keeping the memory of the old railway workshop alive”. In this sense, the discussion about The blue building might emphasize the notion that in contexts of conflict, history and local narratives are often divergent and ambiguous (Bilali & Mahmoud, 2017), and are therefore bound to comprise different ideas and values to different people.

“... that some people start to proclaim that this is such a beautiful building … I know that many of them have never been unemployed and have never had to deal with this shit building.”

But there are two categories of comments that might be even more revealing. The first is connected to an episode of the city’s history that is not normally brought up in relation to Tilburg’s narratives of ‘beautiful ugliness’. After the industrialization had boosted the city’s prestige and wealth to novel heights (Kappelhof et al., 1997), the collapse of Tilburg’s textile industry caused unemployment rates to soar (Tilburg.com, 2009), and deepened the poverty that already pervaded several neighborhoods of the city (Regionaal Archief Tilburg, 2018). The buildings from the 60s and 70s still remind older inhabitants of this period of upheaval and sorrow. And The blue building in particular symbolizes their desolation, as it was the location where unemployed Tilburgers had to report about their desperate situation in order to receive benefits. In this sense, to some, The blue building appears to be a significant note in a network of the surveillance and patronization of the poor. Quite understandably, one Facebook user argues: “... that some people start to proclaim that this is such a beautiful building … I know that many of them have never been unemployed and have never had to deal with this shit building.” The discussion about the historic function of the building further emphasizes the observation that the building is a ‘stigmatized space’, and might demonstrate how the general debate about the building showcases the ongoing divide between the impoverished inhabitants of the city and ‘the rest’ — or; those who have been affected by unemployment and those have not.

These screenshots show some other comments that were posted in response to a Facebook post of The blue building.

A second critical category of comments calls into question the validity of the values that underpin the dominant thrust of the argument by challenging the idea that ‘demolition’ would be a logical conclusion to the observation that a building is ‘ugly’ — noting that, if this perspective becomes hegemonic, “half of the city should be demolished” —, and proposing that not everything always needs to be beautiful. In this sense, these comments appear to share some of the views of the critical heritage studies movement, which tries to highlight the problematic nature of the manner in which the "authorized heritage discourse (AHD) focuses attention on aesthetically pleasing material objects, sites, places and/or landscapes that current generations ‘must’ care for, protect and revere so that they may be passed to nebulous future generations" (Smith, 2006, p. 29). Taking this perspective into account, The blue building should not be protected because some people find it 'beautiful', nor should it be destroyed because others find it 'ugly'.

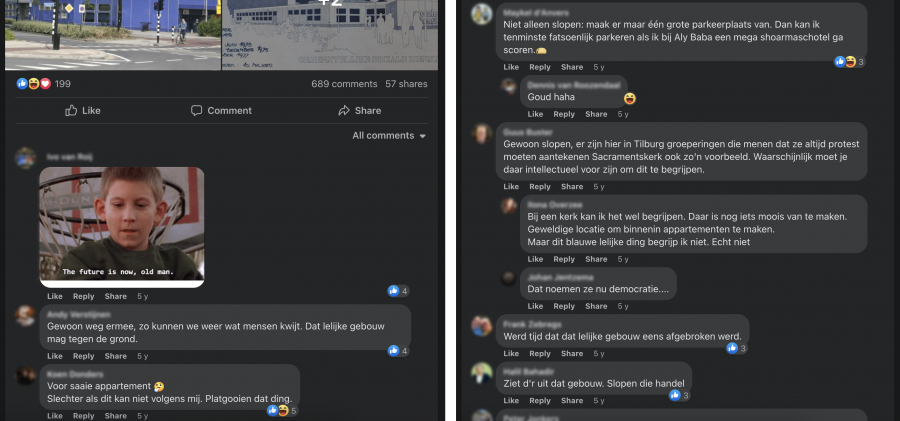

The old and intellectual elites

The projected demolition of The blue building was also discussed on other social media platforms and Facebook pages, often echoing the themes and perspectives that were also mentioned on the pressure group’s Facebook page. For the purpose of this article, these posts provide additional opportunities to elaborate upon the annoyance that was observed earlier. The comments that were produced underneath a popular post in the ‘Heel Tilburg in Een Groep!’ Facebook group — which translates as ‘The Whole of Tilburg in One Group!’ — demonstrate how negative emotional responses can often be linked to a sense of deferred or denied purposeful potentiality, as The blue building is allowed to stand vacant while a national housing crisis forces many Tilburgers to live in unfavorable conditions (Woningnood Tilburg, 2021), and the people who live in De Spoorzone struggle to park their cars close to their homes.

These screenshots show comments that were posted in response to a Facebook post on the 'Heel Tilburg In Een Groep!' Facebook page.

Though heritage professionals describe safeguarding cultural heritage as a necessary practice for an enduring sense of individual and collective belonging, and for the joy and survival of diverse communities (UNESCO, 2022), the less 'well off’ members of these communities aptly demonstrate how certain cultural practices can be perceived as a privilege or luxury some people simply cannot grasp, nor afford. Responses that, for instance, mention that “you probably need to be an intellectual to be able to understand this”, point towards the predominantly “elite nature” of heritage activism (Arabindoo, 2015), and demonstrate that the quest to save The blue building because of its beautiful ugliness might not merely underscore historical divides, but may also reproduce and update social divisions in the present time.

This picture shows The blue building and some demolition work taking place on February 2, 2023.

Away with the old ‘ugly’, and in with the new

If all goes to plan, The blue building’s dust should literally begin to settle in the course of the next few months. The digital discussions that took place while the building was heading towards its eventual destruction, demonstrate how buildings can be understood from various, often conflicting perspectives, and can therefore encompass radically different meanings. From a cultural and architectural perspective, The blue building was logically interpreted as either ‘beautiful’ or ‘ugly’ — or at least architecturally relevant or irrelevant —, and was therefore understandably embraced by architecture lovers and supporters of Tilburg’s ‘beautiful ugliness’. But from historical and functional points of view, the building represented much more profound ideations. For decades, it served as a reminder of general traumas like the city’s history of radical demolition and pervasive poverty, and of more intricate and personal traumas that were induced by the building’s function.

In general, Tilburg’s ironic and celebratory ‘beautiful ugliness’ narrative might have the potential to democratize culture and provide the inhabitants of the city with a constructive and comforting attitude to deal with their shared grief. The case of The blue building, however, demonstrates that perspectives and identities that are normally humorous and uplifting can cause anger and confusion if they fail to properly incorporate the layered dimensions and values that distinguish a particular ugly building from another. The demolition of The blue building will probably help to provide some solutions for the contemporary crises Tilburg is dealing with. With respect to the city’s historic crises, however, it must be noted that the removal of the building also implies the removal of a natural conversation starter. When the day comes that a new, generic looking apartment building rises at the location of the former blue building, it is important not to forget that erasing ugly buildings is relatively easy — especially in an experienced city like Tilburg —, but erasing traumatic memories and historically constructed poverty remains hard.

References

Arabindoo, P. (2015). Isolated By Elitism: The Pitfalls Of Recent Heritage Conservation Attempts In Chennai. New Architecture and Urbanism: Development of Indian Traditions, 155–160. https://doi.org/10.5848/csp.1892.00022

Beekmans, I. (2019, February 8). Deconstructing Tilburg: the Heilig Hartkerk. Diggit Magazine.

Beversluis, M. (2017, May 8). Naam | Martin Beversluis. Martin Beversluis.

Bilali, R., & Mahmoud, R. (2017). Confronting History and Reconciliation: A Review of Civil Society’s Approaches to Transforming Conflict Narratives. History Education and Conflict Transformation, 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54681-0_3

BN DeStem. (2017, June 17). Lelijkste gebouw van Tilburg blijft lelijk. bndestem.nl.

Brabants Dagblad. (2017, March 11). UWV-pand Spoorzone: gedrocht of juweel? bd.nl.

De Erfgoedstem. (2021, July 30). Het Blauwe Gebouw, Tilburg is het behouden waard.

De Gram, P. (2017, October 26). ‘Blauwe gebouw belangrijk voor Tilburg.’ MONUMENTAAL.

Dutchtowns. (n.d.). Dutchtowns.com - Tilburg dutch historic town- Nederlandse historische stad.

Erfgoedvereniging Heemschut. (2018, January 19). Heemschut verzet zich tegen sloop Blauwe Gebouw.

Geerts, J. (2018, March 2). Stand van zaken met het Blauwe gebouw Oude Sociale dienst. Tilburgers.nl.

Godefroy, N. (2021, January 3). Blauwe Gebouw verdwijnt: 150 appartementen erbij in de Spoorzone. Indebuurt Tilburg.

Kappelhof, T., Kolman, C., Kooij, B., Olde Meierink, B., Reijs, N., & Stenvert, R. (1997). Historie, Monumenten in Nederland. Noord-Brabant. DBNL.

Koningsberger, V. (2017, October). Voormalige kantoorgebouw voor de Sociale Dienst Tilburg Beschrijving en waardering. Google Docs.

Moses, S. R. (2015). STIGMATIZED SPACE: NEGATIVE HERITAGE IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION.

Moshenska, G. (2020). ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS AS SITES OF PUBLIC PROTEST IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY BRITAIN. Fennoscandia Archaeologica.

Omroep Brabant. (2019, February 25). De Katterug in Tilburg is de lelijkste plek van Brabant.

Pijnenburg, T. (2017, May 8). Actief voor de stad; de oude soos. Gilaworks.

Pijnenburg, T. (2020, July 8). Doek valt definitief voor Het Blauwe Gebouw. Het Blauwe Gebouw.

Raad van State. (2020, June 24). Uitspraak 201902208/1/R2. Raad Van State.

Regionaal Archief Tilburg. (2018, May 24). Een kijkje in het leven in de Koningswei.

Smith, L. (2006). Uses of Heritage. Routledge.

Tilburg.com. (2009, November 11). De jaren zeventig in Tilburg.

UNESCO. (2022, July 21). Cultural heritage.

Van Boesschoten, F., [ Dinkydau00]. (2011, September 3). Fred van Boesschoten - Tilburg is grijs en grauw [Video]. YouTube.

Van Dael, A. (2017, July). Oude UWV-pand: erfgoed of sloop? Journalistiek En Meer.

Van de Donk, B. (2017, March 14). Geen gezicht. bd.nl.

Van Den Dries, M. (2021, December). “Meer dan alleen redden en behouden.” Erfgoed Magazine Tilburg.

Van Der Schaaf, P. A. (2017a). Lokaal Tilburg stelt vragen over ‘Het Blauwe Gebouw.’ Tilburgers.nl.

Van Der Schaaf, P. A. (2017b, May 8). Gezocht: nieuwe naam voor het MCSI-gebouw. Tilburgers.nl.

Van der Vliet, R. (2017, September 4). Hoe zit het nou met het blauwe gebouw in de Spoorzone? Indebuurt Tilburg.

Van der Vliet, R. (2022, November 3). Het Blauwe Gebouw wordt snel gesloopt. Indebuurt Tilburg.

Van Hest, E. (2020, December 22). ‘Lelijkste gebouw’ van Tilburg maakt plaats voor 150 woningen in de Spoorzone. ed.nl.

Vermeer, B. (2018, June 20). Een ode aan de lelijkste Tilburgse panden: grindtegelgevels en andere “clusterfucks.” bd.nl.

Vermeer, B. (2020, January 23). Tilburg is hoogtepuntje in de reisgids Treurtrips: ‘Aangenaam pauper.’ bd.nl.

Wassens, R. (2013, August 14). Welkom in Tilburg: Brabants lelijkste eendje. Univers.

Wiki Midden-Brabant. (2021, February). UWV-pand (oud) - Wiki Midden-Brabant.

Woningnood Tilburg. (2021). Woningnood Tilburg - HOME.