How Google Arts & Culture is challenging and reproducing ‘The Museum’

Google launched the Google Arts & Culture project — ‘GAC’ from now on — in 2011 in collaboration with 17 museums (Delacroix, 2018). Today, the project contains content from over two thousand museums and has expanded its activities towards archives, heritage sites and other cultural organizations. According to Google, the GAC aims “to preserve and bring the world’s art and culture online so it’s accessible to anyone, anywhere” (Google Cultural Institute, n.d.). Previous research has, amongst other things, analyzed the features of the GAC website (Wahyuningtyas, 2017) and has engaged with the impact of its affordances on the ways in which people view art and other cultural objects (Lee, Kim & Lee, 2019; Zhang, 2020). Though some research mentions copyright issues, hitherto no critical analysis of the project was conducted in relation to more content-based challenges that are currently debated within the field of museology. Therefore, this article explores the manner in which Google Arts & Culture is addressing, (re)producing and transforming some of the current issues within the field of museology in relation to its digital context. Through this exploration, this article aims to gain insights into the impact Big Tech and digital platforms might have on current museological issues, and to provide critical questions and leads for future research.

On the GAC “Collections”-page, over 2800 museum collections are made at least partially accessible.

This screenshot shows the GAC “Collections”-page. As a default, all museums are shown.

For the purpose of this article, three collections from Belgium and the Netherlands were selected for in-depth analysis; the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, the Museum of Natural Sciences in Brussels and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Other collections, components of GAC and expressions about the Google project are perceived as relevant contextual data. The three collections were selected based on the assessment that they provide opportunities to discuss questions about structure and classification, ethical issues, and audience engagement, participation and inclusion. These subjects will be discussed following an introductory analysis of Google’s discursive use of concepts like ‘museum’ and ‘collection’.

The meaning of 'museum(s)'

Recently, discussions have been taking place about the meaning of ‘museum’ in response to the International Council of Museum’s — ‘ICOM’ — efforts to establish a new museum definition (ICOM, 2020). The five potential new definitions that were initially produced by ICOM — from which one was recently selected to become the new official definition (ICOM, 2022) — deviated from the previous definition by, amongst other things, arguing a museum should inspire the public and evoke emotions, by focusing on practices like participation and inclusion, and by emphasizing the importance of concepts like sustainability, memory, discovery and identity. One of the five definitions proposed to broaden current approaches by including “natural” heritage, whereas the other definitions focused on “tangible and intangible heritage”. Similar to the previous definition, most of the five new definitions payed attention to exhibition, conservation, research, education and enjoyment.

Though there is no formal partnership between ICOM and GAC, there are some links between the organizations. During the 2021 ICOM conference, for instance, a talk was given by GAC Partnerships Manager Ana Elizabeth Gonzalez (The British Museum, 2021), and Edmund Connolly, another GAC Partnerships Manager, is a member of the ICOM UK committee. It might therefore not come as a surprise that GAC describes itself with words that resemble parts of ICOM’s museum definitions (Google Cultural Institute n.d.). Both ICOM and GAC make being “non-profit” — the new definitions use the term “not-for-profit” instead — a central feature of their texts. Also, both ICOM's previous definition and GAC's texts deal with notions of preservation and accessibility. Other parts of the GAC ‘About’-page promote activities like “meet the people, visit the places and learn…” (ibid); thereby promoting ideas that are both present in the previous and new ICOM definitions, which partially revolve around learning and interacting with new people and culture(s). Furthermore, Google employs familiar terms like “Museums” and “Collections” to refer to digital sets of objects and employs traditional museums and their physical locations to organize these collections on its main “Collections”-page.

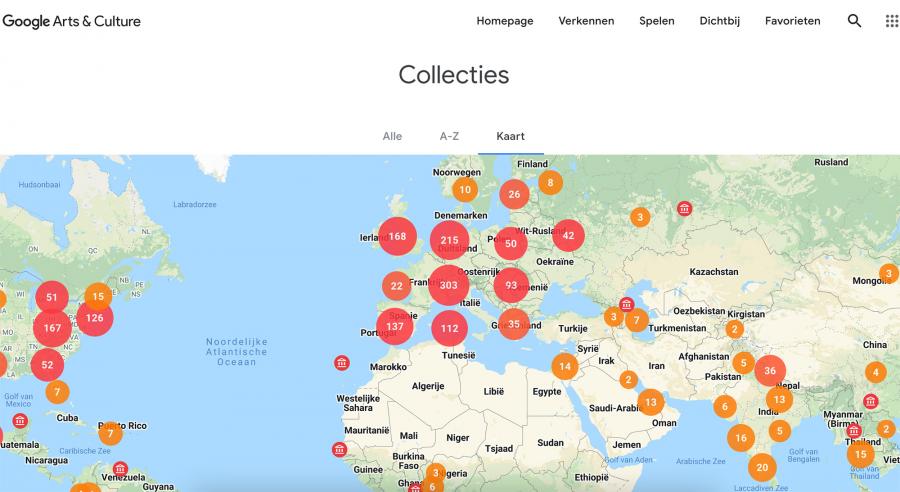

This screenshot shows the GAC “Collections”-page. The physical locations of the museums can be used by visitors to organize the museums visually, on a map of the world.

The museum and its (non-)physical structure

Organizing collections based on physical locations might feel like a ‘natural’ way to structure museological content; research shows how museum buildings are often considered very much a part of museum practices and experiences (Jones & MacLeod, 2017). In the case of GAC, however, the decision to organize content this way might be strikingly conservative and unimaginative, since the digital properties of the platform also allow for other approaches towards organizing and structuring content. Its technical capabilities could, for instance, permit the platform to behave more like French writer and politician André Malraux’ Musée imaginaire (Andersson, 2021) — an imaginary museum that contains all the art of the word without physically possessing it. Malraux, for example, created his ideal ‘musée de la sculpture’ by printing and arranging pictures of sculptures in “free association” (Pontzen, 2020). The GAC ‘museum’, however, fails to facilitate this type of individual, philosophical freedom. The platform’s “Collections”-page, in this sense, clings to notions of physical spaces and is constrained by rigid technical choices (Andersson, 2021).

Yet, moving beyond the main “Collections”-page, physical museums and the GAC collections start to diverge — a divergence that depends on the content that is submitted by the museums. For instance, before users interact with the 87 artworks in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts’ digital collection, the artworks are arranged in two ways: (1) based upon a somewhat ambiguous categorization of artistic movements and, (2) their popularity. The artistic movements — “Baroque”, “Renaissance”, “Antwerp school”, “Portrait”, etc. — are thereafter ranked based on the size of their relative share. This causes paintings that are classified as “Baroque” to be displayed first. Visitors who interact with the webpage can also rank the artworks based on their colors and specify which colors they would prefer to see. Visitors who click on a color receive a ‘badge’ to compliment them on their engagement. Though ranking collections based on color is probably still a long way from the “free association” (Pontzen, 2020) Malraux envisioned, it does allow visitors to detach themselves from the often fixed order that is present within physical museum collections.

This screenshot shows how the artworks of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp are ranked when the audience selects the color dark red.

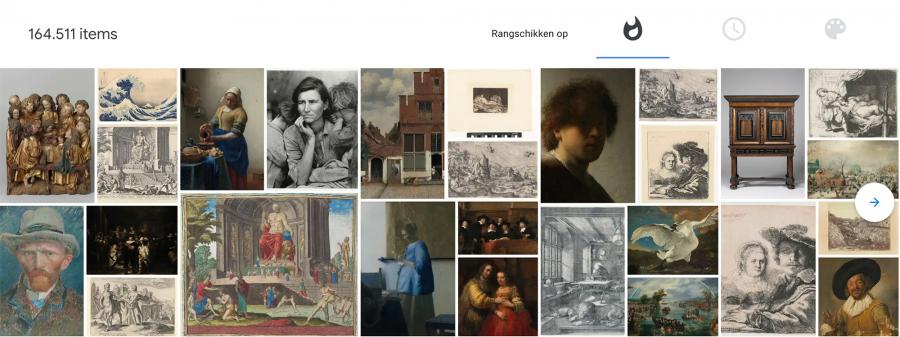

The digital structure of the Dutch Rijksmuseum is even more elaborate. Within its main collection, visitors first get the option to explore one of the collection’s 11 “stories”. Thereafter, the collection is categorized according to a variety of artistic movements that are just as ambiguous as the categories of the Museum of Fine Arts — including “Baroque”, “Amsterdam” and “Mammal”. A research that examined the practical functioning of GAC concludes that “Baroque” is the most common art movement within the project (Wani, Ali & Ganaie, 2019); demonstrating that the dominance of this category in the collections of the Rijksmuseum and the Museum of Fine Arts is a prevalent phenomenon on GAC.

This screenshot shows how the artworks of the Rijksmuseum are ranked based on popularity before the audience interacts with the ranking functionalities. Next to the flame icon — ‘popularity’ —, the clock icon and palette icon refer to time and color.

Precisely because of their ambiguity, the categories appear to be somewhat reminiscent of a classification of animals that was addressed by French philosopher Michel Foucault in The Order of Things (1994). According to Foucault, categorizations — or ‘classifications’ — are artificial and force people to think and talk about things in preconditioned manners (ibid; Snyder, 1984). In this sense, categorizations are part of top-down discursive systems that construct which actions and ideas are permissible and possible (Cameron, 2001; Cameron & Panovic, 2014). Looking at the categories that are employed in the GAC collections, we might argue that, according to Google, viewers must focus on artworks’ style periods — preferably “Baroque” —, their locations, their popularity — a category that will be discussed in more detail in the next part of this article — their creators, and sometimes on their subjects — “Mammal”, for instance. Thus, Google is not just prescribing how people should see artworks, it's also producing criteria and categories that indicate what artworks might be.

Reproducing popularity

Unlike the Museum of Fine Arts, the 164.511 artworks that are present in the digital collection of the Rijksmuseum can also be arranged by time. Visually and structurally, this time-function is favored over the option to rank the artworks based on their colors, but subordinate to the option to rank the artworks based on their popularity. The latter is the preferred filtering option in every collection on the platform. Considering that the different art movements are automatically ranked based on their relative size and the elevated status of the popularity-function, the concept of ‘popularity’ appears to be a dominant force on the platform. This is hardly surprising. Since the emergence of the internet, ‘popularity’ was deemed the most appropriate indicator for ‘wide popular consent’ and was therefore considered a useful concept in the quest to present users with relevant content (Federici et al., 2010). Recently, however, this approach is often described as a “rich-get-richer” effect, or linked to the idea of “popularity bias” (Vall et al., 2019); meaning that content that is already highly visible is rendered even more visible, while innovative content that challenges dominant beliefs is increasingly concealed. Logically, at the Rijksmuseum collection-page, a van Gogh portrait is amongst the first artworks on display. Because of the painting’s prominent position, it’s likely to receive more clicks, which will ultimately lead to the further strengthening of its popularity.

The popularity-function can, however, also trigger unexpected results. The most popular artwork of the Rijksmuseum, according to GAC, is a wooden sculpture called “the last supper”. In the physical Rijksmuseum, this artwork is by no means the most popular object. However, because it has the same name as Leonardo da Vinci’s “last supper”, it is displayed as a suggestion when people search for da Vinci’s painting, and consequently clicked on. Thus, factors that would normally not impact the visibility of an artwork, can have major consequences in digital museum environments.

Even though the technical affordances of Google Arts & Culture sometimes cause less obvious artworks to be promoted, in general, GAC seems to be inclined to reproduce existing ideas about what is ‘good’ and interesting.

Ultimately, even though the technical affordances of GAC sometimes cause less obvious artworks to be promoted, in general, GAC seems to be inclined to reproduce existing ideas about what is ‘good’ and interesting. This socio-technical mechanism is therefore also likely to counteract the intention of the Association of Critical Heritage Studies to resist the Authorized Heritage Discourse — ‘AHD’ from now — and “to promote a new way of thinking about and doing heritage” (Smith, 2012). Heritage researcher Laurajane Smith defined the AHD as a “dominant Western discourse” that “naturalizes certain narratives and cultural and social experiences” and is “reliant on the power/knowledge claims of technical and aesthetic experts, and institutionalized in state cultural agencies and amenity societies.” (Smith, 2006) Precisely because these agencies are now collaborating with a dominant tech company that highly values ‘popularity’, chances to promote new perspectives online might be diminishing. A research that analyzed the perspectives that are present on GAC finds that, indeed, urban and Western perspectives are being prioritized on the platform (Kizhner et al., 2020).

The ethics of displaying cultural heritage

As part of her resistance against the AHD, Smith also describes how museums are imbued by inequities and colonialism. She criticizes, for instance, the manner in which museums “have dealt with human remains and other items of cultural value” — specifically those of Indigenous people. In 2021, the Rijksmuseum launched multiple initiatives to address slavery and colonialism in relation to its collection (Rijksmuseum, 2021). Though associated themes and perspectives are not emphatically present on the GAC-page of the Rijksmuseum, they can be discerned in the descriptions that accompany some artworks. A text about a painting from Aelbert Cuyp, for instance, uses the words “enslaved servant” and “enslaved man” instead of “slave”. These words reflect critical perspectives on colonialism; specifically the notion that the “adjective enslaved reveals that though in bondage, bondage was not [his] core existence” (Telfair Museums, 2020).

This screenshot shows a painting by Aelbert Cuyp. The short description of the painting reads: “A leading merchant from the Dutch East India Company with his wife and an enslaved servant”.

Regarding items of cultural value that were taken from other societies, however, the Rijksmuseum appears to be less forthcoming on GAC. Objects like the Banjarmasin diamond — which is still on display in the physical Rijksmuseum (Rijksmuseum, n.d.) — are not even present in the museum’s online collection. Despite the fact that the Rijksmuseum spoke openly about returning stolen artifacts a few years ago (Boffey, 2019), the subject appears to be circumvented on the online platform.

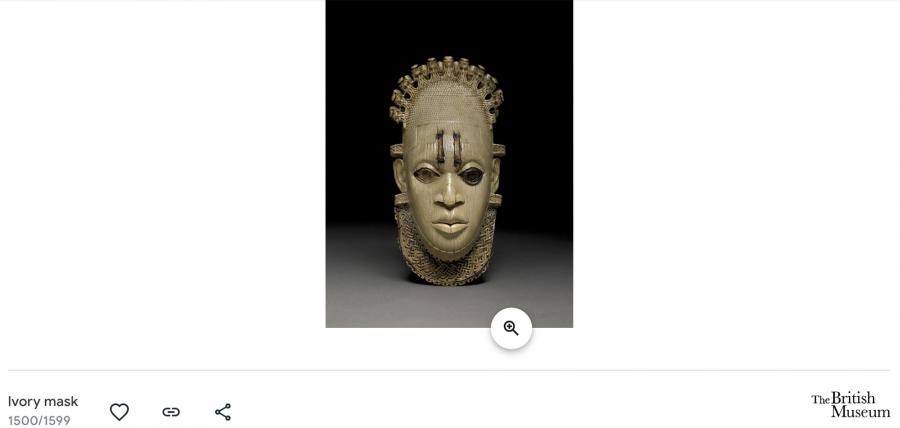

Interestingly, other collections demonstrate a different approach towards stolen objects. One of the looted Benin Bronzes (Marshall, 2021), for instance, is proudly shown on the GAC-page of the British Museum. Near the end of the text that accompanies a picture of the sculpture, it is mentioned that: “the British launched a punitive expedition against Benin in response to an attack … Numerous royal objects, including this ivory mask, were seized…”. Discursively, the text justifies — “in response to” — the actions of the British and frames the objects as being “seized” rather than “stolen”. In this sense, the possession of the mask is presented as both just and rational. The difference between the approaches of the Rijksmuseum and The British Museum might indicate that, even though Google allows museums to promote inclusive language and critical perspectives, it does not oblige them to do so. Consequently, museums can use Google’s online reach as they see fit; to challenge obsolete, colonial discourses or to reinforce outdated colonial power structures and questionable ownership.

This screenshot shows an “Ivory mask” that is in the GAC- collection of The British Museum.

Displaying human remains

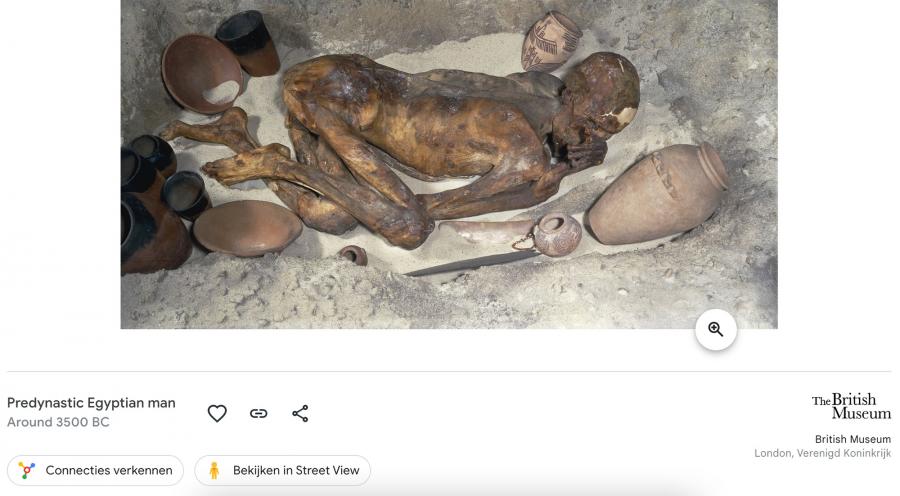

The British Museum also does not appear to factor in Smith's criticism regarding human remains. The “gebelein man” (Fletcher, Antoine & Hill, 2014, p. 60) is on display on its collection-page and in its physical museum. The latter is emphasized online by a “Watch in Street View”-button that is shown underneath the picture and title of the ‘object’.

This screenshot shows the body of a “Predynastic Egyptian man” that is in the online collection of The British Museum. The second button invites the audience to “Watch in Street View”.

Though the British Museum might be a familiar name in discussions about displaying human remains (Joy & Farley, 2019), it's far from the only museum that shows human remains on its collection-page. The Museum of Natural Sciences in Brussels, for instance, shows multiple human fetuses in its “Belgium”-category.

This screenshot shows some of the 57 objects from the Museum of Natural Sciences in Brussels that are categorized as ‘Belgium’. The image in the middle shows “human fetuses”.

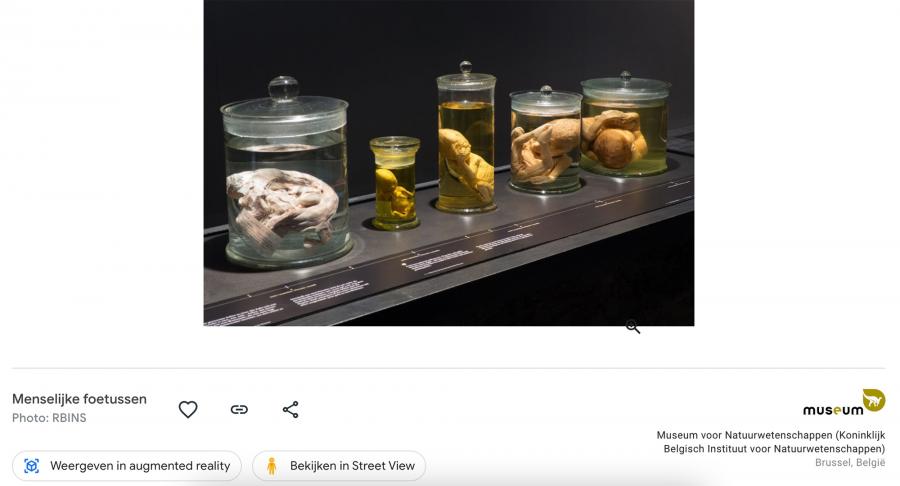

Different perspectives on displaying human remains still exist. According to sociologist Tiffany Jenkins, most museum visitors support this practice, while museum staff and minority groups are often less in favor of it (Kennedy, 2010). To respond to the various, often conflicting views, some museums have adapted the manner in which bodies are shown; for instance by partially covering them, or by providing warning labels (ibid). On GAC, however, none of these measures are taken. Even more, the ambiguous categorization that was addressed earlier might cause visitors to be confronted with human remains unexpectedly; people who visit The Museum of Natural Sciences online might not expect to see fetuses after clicking the “Belgium”-category.

This screenshot shows the human fetuses that are part of the Museum of Natural Sciences in Brussels online collection. The first button calls to “Show in augmented reality”.

Despite continuing discussions, most people appear to agree that human remains should be handled with respect and should not be used for mere entertainment. However, strong public interest in human remains — combined with the need to attract visitors — might cause museums to produce displays in which bodies serve as ‘spectacles’, rather than as sources of information and education (Cassandra, 2012). On GAC, this tendency is also present, and might even be taken to a higher level through the “Watch in Street View” and “Show in augmented reality” buttons, which both appear to lack an added educational value and might therefore be considered features that were designed merely to engage and entertain (Carmigniani et al., 2010).

Designing interaction and participation

As mentioned before, notions of ‘participation’ and ‘inclusion’ play a significant role in new approaches towards museums. Though GAC might appear to encourage participation at first glance via its impressive range of interactive functions — which also include a number of games and challenges that were found to “stimulate the student's curiosity” (Verde & Valero, 2021) —, visitors of the platform are not truly empowered and included, since contribution is only allowed via “your museum, institution, or collection” (Google, n.d.). In practice, this entails that only cultural professionals from recognized organizations can play an active role in the project.

Whilst GAC might fail to generally empower and include people, its interactive features may have a positive effect on learning efficiency and outcomes. Specifically the option to receive ‘badges’ is often considered a technical function that can encourage “desired practices” (Hakulinen, Auvinen & Korhonen, 2013) and might have a positive impact on motivation and performance (Kyewski & Krämer, 2018). People that interact with GAC can earn 20 badges, which include badges for reading texts on the platform in their entirety and for looking at a single artwork for an extended period of time.

This screenshot shows some of the ‘badges’ — or ‘achievements’ — that can be earned on the GAC platform. Badges that are shown in full-color are earned, badges that are shown in shades of grey are not yet earned.

The use of ‘badges’ is part of the overarching trend of gamification. Research shows that enhanced learning outcomes can often be linked to extended “time-on-task” periods that are attributed to gamification functions (Landers & Landers, 2014). Interpreting this in relation to the concept of “attention economy” — the notion that human attention is an “increasingly scarce resource[s]” that can be converted into money —, we should consider the idea that for Google, the quality of learning outcomes is subservient to gamification’s potential to elongate visits to its platform. This possible interpretation might be supported by criticism on some GAC functions that are linked to its badges. People can, for instance, earn a badge for zooming in on an artwork as much as technically possible. In relation to this function, cultural professionals have argued that artists never intended their artworks to be viewed in this much detail (Culture & Creativity, 2016). In this sense, Google appears to be promoting new online practices that might challenge and jeopardize the preferences and expertise of cultural professionals in order to boost its visitor engagement.

The online future of arts and culture

This article aimed to produce new insights and leads for future critical analysis with regard to the role GAC and digital environments play in relation to the (re)production and transformation of some of the current issues within the field of museology. Through its variety of interactive features and its comprehensive size, GAC allows individuals to access and interact with museological content in informative and engaging ways. Though this might encourage people to interact with art and culture in new ways and gives more people access to culture in general, there are serious issues concerning GAC that might not merely impact cultural organizations, but could affect culture in general. The platform’s strong focus on popularity, its implementation of rigid physical and technical structures and its authorisation of texts and images that reproduce traditional Western views, combined with Google’s online dominance, might strengthen the AHD and counter initiatives to renew and develop the fields of cultural heritage and museology. Furthermore, its approach to interaction and gamification could, alongside positive educational effects, also lead to the transformation of serious cultural artifacts — and even human remains — into objects of spectacle and entertainment, and might provide people with a false sense of empowerment. It must also be noted that Google’s intentions with the platform — which probably include the retention of attention for its own economic benefit — remain partially hidden. More knowledge about the latter might help future critical analyses of GAC and could inform future collaborations between GAC and museums to ensure these collaborations won’t negatively impact the future of arts and culture.

References

About Google Cultural Institute. (n.d.). About Google Cultural Institute.

Andersson, M. (2021). Entering the Imaginary Museum: Comparing André Malraux’s Theory of Aesthetics with the Google Arts & Culture online Platform. Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi.

Boffey, D. (2019, March 15). Rijksmuseum laments Dutch failure to return stolen colonial art. The Guardian.

Cameron, D. (2001). Working with Spoken Discourse. SAGE Publications.

Cameron, D., & Panovic, I. (2014). Working with Written Discourse. SAGE Publications.

Carmigniani, J., Furht, B., Anisetti, M., Ceravolo, P., Damiani, E., & Ivkovic, M. (2010). Augmented reality technologies, systems and applications. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 51(1), 341–377.

Cassandra, B. R. (2012). Human bodies and reliquaries on display: The tension between education and spectacle in museum and religious spaces. Senior Honors Projects.

Culture & Creativity. (2016, January 6). GOOGLE ART PROJECT: HOW THE BIGGEST MUSEUM COLLECTION IN THE WORLD IS ORGANIZED.

Delacroix, S. (2018, October 25). New ways to experience The Met on Google Arts & Culture. Google.

Faber, N. (2021, April 13). Should your Museum Partner with Google Arts and Culture? Cuberis - Museum Website Design and Development.

Federici, S., Borsci, S., Mele, M. L., & Stamerra, G. (2010). Web popularity: an illusory perception of a qualitative order in information. Universal Access in the Information Society, 9(4), 375–386.

Fletcher, A., Antoine, D., & Hill, J. D. (2014). Regarding the Dead. British Museum.

Foucault, M. (1994). The Order of Things. Routledge.

Google. (n.d.). Google Cultural Institute - Join Us! – Google.

Google Cultural Institute. (n.d.). About Google Cultural Institute. Google Arts & Culture.

Hakulinen, L., Auvinen, T., & Korhonen, A. (2013). Empirical Study on the Effect of Achievement Badges in TRAKLA2 Online Learning Environment. 2013 Learning and Teaching in Computing and Engineering.

ICOM. (2017, July). Statutes of the International Council of Museums.

ICOM. (2022b, August 24). ICOM approves a new museum definition. International Council of Museums.

Jones, P., & MacLeod, S. (2017). Museum Architecture Matters. Museum and Society, 14(1), 207–219.

Joy, J., & Farley, J. (2019). The Curation and Display of Lindow Man. Journal of Wetland Archaeology, 19(1–2), 172–185.

Kennedy, M. (2010, October 25). Museums avoid displaying human remains ‘out of respect’. The Guardian.

Kizhner, I., Terras, M., Rumyantsev, M., Khokhlova, V., Demeshkova, E., Rudov, I., & Afanasieva, J. (2020). Digital cultural colonialism: measuring bias in aggregated digitized content held in Google Arts and Culture. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities.

Kyewski, E., & Krämer, N. C. (2018). To gamify or not to gamify? An experimental field study of the influence of badges on motivation, activity, and performance in an online learning course. Computers & Education, 118, 25–37.

Landers, R. N., & Landers, A. K. (2014). An Empirical Test of the Theory of Gamified Learning. Simulation & Gaming, 45(6), 769–785.

Lee, J. W., Kim, Y., & Lee, S. H. (2019). Digital Museum and User Experience: The Case of Google Art & Culture. International Symposium on Electronic Art.

Marshall, A. (2021, October 29). This Art Was Looted 123 Years Ago. Will It Ever Be Returned? The New York Times.

Pontzen, R. (2020, May 6). Het beroemde imaginaire museum van André Malraux nodigt nu meer dan ooit uit tot navolging. de Volkskrant.

Riessman, C. K. (2012). Analysis of Personal Narratives. The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft, 367–380.

Rijksmuseum. (n.d.). The Banjarmasin Diamond, anonymous, c. 1875.

Rijksmuseum. (2021). Slavernij - Rijksmuseum. Rijksmuseum.nl.

Smith, L. (2006). Uses of Heritage. Routledge.

Smith, S. (2012). History. Association of Critical Heritage Studies.

Snyder, C. (1984). Analyzing Classifications: Foucault for Advanced Writing. College Composition and Communication, 35(2), 209.

Telfair Museums. (2020, May 4). Why We Use ‘Enslaved’ ».

The British Museum. (2021, March 18). ICOM 2021 Working Internationally Conference Day 3: The Future of Museums.

Vall, A., Quadrana, M., Schedl, M., & Widmer, G. (2019). Order, context and popularity bias in next-song recommendations. International Journal of Multimedia Information Retrieval, 8(2), 101–113.

Verde, A., & Valero, J. M. (2021). Virtual museums and Google arts & culture: Alternatives to the face-toface visit to experience art. International Journal of Education and Research, 9(2), 43–54.

Wahyuningtyas, S. (2017). ELIMINATING BOUNDARIES IN LEARNING CULTURE THROUGH TECHNOLOGY: A REVIEW OF GOOGLE ARTS AND CULTURE. International Conference Proceedings : Revisiting English Teaching, Literature, and Translation in the Borderless World: My World, Your World, Whose World?, 179–184.

Wani, S. A., Ali, A., & Ganaie, S. A. (2019). The digitally preserved old-aged art, culture and artists. PSU Research Review, 3(2), 111–122.

Zhang, A. (2020). The Narration of Art on Google Arts and Culture. The Macksey Journal, 1.