Reclaiming Public Services: Interview with Satoko Kishimoto from the Transnational Institute

The debate on public services and public alternatives to private ownership models is finding its way back on the academic and political agenda. Citizens and workers all over the world are staging successful campaigns to return privatised services back into public hands. One particularly interesting and deserving contribution to a debate which is both highly technical and daringly political has been the study Reclaiming public services. How cities and citizens are turning back privatisation. It brings together an impressive body of “remunicipalisation” cases situated in many different economic sectors and countries.

Remunicipalisation happens whenever a city decides to take back ownership and control of privatised our outsourced services. There can be many motives behind them but the outcomes are generally the same everywhere. Remunicipalisations are quite successful in bringing down costs and tariffs, while improving working conditions and service quality as well as transparency and accountability.

During the preparation for their symposium We Own It! On Public Ownership on 26th April in Vooruit, Ghent, ACOD Cultuur (the socialist union for cultural workers in Belgium) interviewed one of the invited speakers, Satoko Kishimoto, coordinator of the Public Alternative Project at the Transnational Institute and (together with Olivier Petitjean) editor of Reclaiming Public Services.

Remunicipalisation is the new trend. What is so new about it?

The last thirty years, we have been told that market solutions are the only way to go. Expanding the domain of the market would supposedly bring more innovation, more investment and lower service and operation costs. After the financial crisis, privatization pressures have even intensified in a political climate of austerity which forces governments to work down their debts instead of investing in public services.

But workers and citizens are starting to understand that privatization does not bring better services, more investment and technologies. Cracks are starting to appear in the old story and people have had enough of all the negative experiences. Popular movements are looking for public alternatives that are more democratic and accountable while at the same time also more efficient and effective at responding to social, environmental and climate challenges.

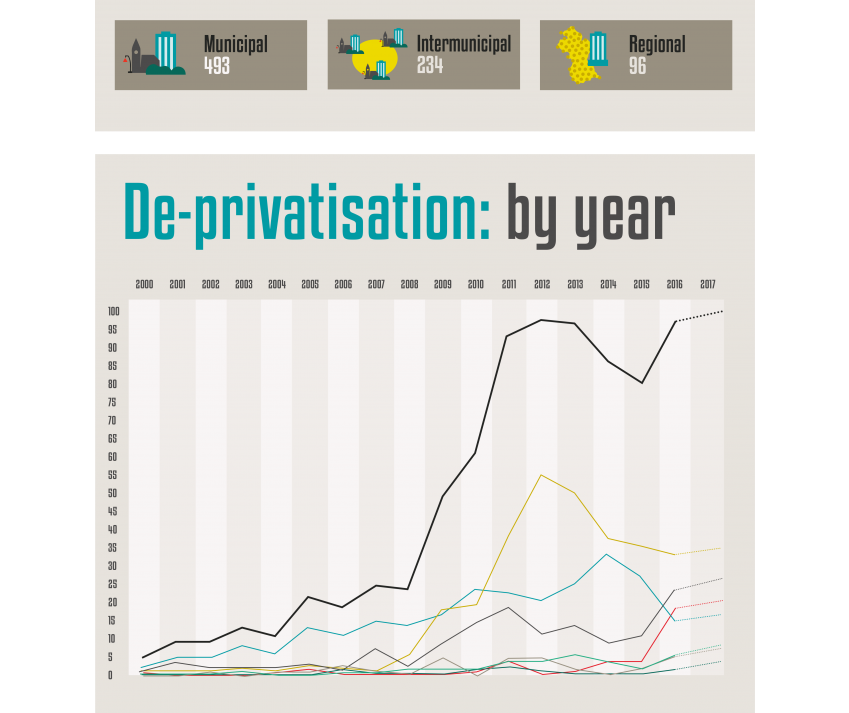

There’s a growing realization that we need a new solution. Importantly, this solution is already happening. With our book Reclaiming Public Services the Transnational Institute and partners provided an overview of how cities and citizens are turning back privatisation. In total, we have documented 835 cases of (re)municipalisation of public services involving more than 1600 cities in 45 countries.

How does remunicipalisation compare to nationalisation?

The return of privatized services into the public sector can also occur at the initiative of central governments and there can be many motives behind re-nationalisation. For instance, what we witnessed in the aftermath of the financial crisis was the nationalisation of several banks in both the USA and Europe. The goal, however, was never to re-orientate these financial institutions towards more sustainable trajectories in an economic, social and environmental sense. It was about taking over the bad debt in order to privatize whenever the market was ready again.

Nuclear energy provision in Japan provides another example of a government stepping in to temporarily fix private failure. The nuclear reactor of Fukushima was privately owned by TEPCO. After the Fukushima disaster, the Japanese government nationalised the company. It intends to privatise the TEPCO shares when market conditions and private investor trust becomes favourable again.

"Popular movements are looking for public alternatives that are more democratic and accountable while at the same time also more efficient and effective at responding to social, environmental and climate challenges."

Opposite examples and positive experiments come from Latin America. Many re-nationalisations here have very clear social objectives, for instance to make services available and affordable for the entire population. We nevertheless decided to focus on (re)municipalisation because they relate more closely to the local public interest and direct citizen needs. People have a direct interest in strong public services where they live and work. There exists a large potential to mobilise and organise around heartfelt problems and needs. It is the reason so many popular movements are picking up the gauntlet at the local level.

What is so problematic about Public-Private Partnerships? Do they represent value for money?

is actually very easy to give examples of failed PPP from the United Kingdom where they actually use the term Private Finance Initiative instead of PPP. The dynamics behind PFI or PPP are really the same. In the UK it refers to a system where the private sector finances an infrastructure project. There is a big difference with public procurement. Through procurement, a local government can choose a company to build a local hospital or school. The operational management of the service can then be provided by the local government itself or assigned to another company through another procurement contract. PPP, however, is very specific because the contracted concessionary gets control of every step along the way, from financing to constructing and eventually operating the actual service.

The negative consequences for the public are rather substantial. Financing the construction of a new school will almost always involve the borrowing of money. This is the case regardless of whether we are dealing with a PPP or not. But a PPP will cost the public treasury a lot more than a classic public procurement in which case the government takes on the loan itself. That’s because the going interest rates for private companies are many times higher. Whereas governments can loan at one or two percent, private companies can only do so at seven or eight percent. This poses a real problem. It makes a PPP-project that much more expensive and we all pay the price for it.

Reclaiming Public Services

Those supportive of PPP make it appear as if the private sector is providing capital, while in reality PPP is always a pure public expense? So, what makes it attractive?

Totally. After all, we cannot forget that the outstanding debt taken on by the private company for financing a PPP has to be repaid one way or the other. And who pays for it in the end? The public, through taxes and user fees. Also, what would be the point for a private company to just provide capital? That would never happen. They obviously want to make a profit and this expectation is calculated into the price offered to the contracting government. This further explains why a PPP is almost never value for money, at least not from the public point of view.

The attraction of PPP for local governments in Europe has to do with austerity policies. The budgetary rules of the European Union allows a PPP to be recorded off government balance sheet under certain conditions. In that case, the annual expense to the private partner only affects the budgetary deficit (or surplus) but is not added to the public debt. In reality, of course, the debt does not magically disappear. It’s just taken on by the private partner. But the public government – all of us – does pay for it, at higher interest rates!

This is why TNI believes the debt of the PPP should always appear on the public balance sheet. If that would be the case, local governments would not as easily believe the affordability illusion of PPP. When the real financial consequences are shown, governments can make a more informed decision whether it really makes sense to use a PPP.

You mention social and economical reasons in favour of remunicipalisation. But how about ecological reasons?

We live in an era of climate crisis. Energy transition needs to happen quickly. The big energy corporations, however, are not nearly as committed as they should be. The reason is quite simple. With their large fossil fuel reserves, they lack any interest in switching to clean sources of energy. Remunicipalisation on the other hand is a vital element of a serious, all-encompassing thorough transition towards a low-carbon economy that is measuring up to the standards of social justice. Especially in Germany, many municipal companies, often in collaboration with citizen cooperatives, are focussing on the local production and distribution of renewable energy.

Municipalities have a clear interest in nurturing their environment and providing their citizens with affordable, clean energy. But it’s not just the energy sector where municipal services are showing their ecological worth. Take waste disposal services. Private waste companies have no commercial incentive at all to reduce their waste. Having more waste is actually much more profitable. A private company has to keep expensive infrastructures such as incineration ovens running as much as possible. Citizens and local governments on the other hand have a real interest in reducing waste. A municipal waste company allows a city to develop far more integrated waste and recycling policies.

Re-municipalisation can create a window of opportunity for experiments to renew public values.

Same story in the water sector. Private companies don’t want to reduce water consumption. They want to sell more because that’s where profits come from. Contaminated water is another source of profit since it requires capital and chemical intensive technological solutions. So preventing water from getting polluted is not in their interest. Municipal water companies on the other hand have an interest to implement more rational and durable water resource management systems. In Paris, after remunicipalisation, the water company Eau de Paris has been working with farmers who live up stream of the river Seine to reduce their use of chemicals and pesticides. When the water source is less contaminated, producing drinking water is less expensive and more natural.

Let’s continue on that topic. How does the public sector sets itself apart from the private sector? What are the values of the public sector all about?

Allow me to make a fundamental point. They are about universality and affordability. These are the ultimate purposes of public services. Universal access means that services are delivered across an entire city or a whole nation, and not just to the most profitable areas. Affordability, especially when it comes to energy and water, is the corner stone of the public sector’s social mission. Energy has become unaffordable to many, especially in Spain and the UK where 10 to 20 % of families are not able to pay the bills. Private companies can easily drop a non-paying customer unless legal protections are in place. Public utilities, on the other hand, are obliged to keep provide services to citizens.

The attraction of PPP for local governments in Europe has to do with austerity policies."

The protection of workers is another essential public value. Good working conditions are universally important. If you want to provide good public services, you need good paid, highly respected and committed workers. Public emergency workers in Japan are so committed to their public duty. Firefighters, police officers, rescue workers and medical staff give it their best when typhoons or earthquakes occur. In the face of danger, solidarity is naturally happening in the public institutions. Indeed, solidarity is another crucial public service value.

By contrast, in case of exceptional events, the private sector does all it can to exclude liability and responsibility for providing services. This means we have to be extra careful nowadays for what the PPP contracts exactly stipulate. It comes to show private companies are not inherently bound to public duty. All they care for is operating in normal conditions because this of course is far more easy and profitable.

But we are talking about life and death situations here! Can you imagine that when disaster strikes, public governments, local authorities and private concessionaries actually first have to negotiate to find out who has to do what? That is a complete joke but sadly one we hear more and more. Whenever the private sector denies responsibility, the public sector has to step up and is thus forced to carry the biggest risks and costs. But imagine if your normal daily services are operated by a private partner. The public sector gradually loses its expertise, its people, its capacity. Acting in exceptional times hence becomes difficult or even impossible.

How can we mobilize more people behind the idea that public services are crucial for society on a day to day basis. Should we present public services as a right?

Legally speaking, many national laws and constitutions still define water, energy and other essential services as rights. Holding on to these rights is important. Inequality is a real issue in the very extreme neoliberal capitalism of our times. We cannot make a revolution. But at least in this capitalist society, we know public services are the most effective and efficient way to redistribute wealth and create decent living conditions and opportunities for people.

Re-municipalisation is never just about good working conditions. It is about strengthening the community.

Trade unions, progressive parties and research groups like TNI have to create new narratives. We must tell the tales of the people and popular movements that have created better, more democratic and universal public services. We have to raise people’s expectations. There are alternatives to ever more austerity, ever more privatisation. At the same time, we must think about ways of making public services more cost-efficient without resorting to cutting labour like private providers and companies do.

Tackling corruption, for instance, would make more money available to invest in better services manned by highly trained, well-paid workers. People grow tired of corruption scandals. But it would be wrong to assume that privatisation offers a solution here. As if private companies are corruption free or by definition more democratic. This is not the case at all. Corruption involving fraud and the unlawful use of public means is actually a very common problem we encounter with PPP-projects. Another big issue is the lack of transparency.

Can you elaborate on this lack of transparency in relation to corruption?

already starts with notoriously complex PPP contracts. Because of this nature, a government has to budget in average about ten to twenty percent of a PPP project as consultancy fees to legal consultants. Contract complexity, however, does not fully account for these high legal costs. Local governments sometimes have to drag private service providers to court in order to get relevant financial and operational information. Private companies do all they can not to disclose information in the name of commercial confidentiality. A telling example comes from Berlin where city council members could not even look into the contract between the city and the private water company. It took citizen initiatives and a referendum before council members were finally allowed to do so.

Remunicipalisation is a vital element of an all-encompassing transition towards a low-carbon economy measuring up to the standards of social justice.

Tackling corruption is not just about saving money. It’s about transparency and democratic control. Public ownership is not automatically transparent but it is a crucial precondition for democratic public services. It allows citizens to make collective decisions about the kind of public services they want for their societies. But in itself it is not enough. What we need are permanently transparent governance structures like the ones many cities in Spain are developing as we speak.

Citizen platforms are demanding not just remunicipalisation and ownership change, but also accountable, democratic and transparent public services. Citizen-worker participation fuelled by popular movements almost automatically increases transparency. Because if you want to involve citizens in how public services are run and to what ends, you need full disclosure of financial and operational information. You could go a step further. Reserving some seats in the board of public companies for workers, users and communities is what drives back corruption.

How does democracy in action look like?

We use remunicipalisation as a research strategy to demonstrate the systematic failure of privatization. But we need to take it a step further into the realm of political practice. Returning all services to the public sector is probably not realistic in the short term. Many small forms of outsourcing are not necessarily a bad thing as long as the public government retains control about important policies such as prices and working conditions. Therefore, what needs to happen in every city and country is a serious discussion among policy makers, trade unions, civil servants and citizens about the sectors and services that should always be publicly owned and controlled.

We need to determine our priorities. Acting politically requires us to think strategically in terms of goals and the means to achieve them. In Barcelona, the citizen coalition, Barcelona in Comu in power led by Ada Colau, had to work very hard just to get the facts together about the degree of privatisation and outsourcing that had been going on. The previous city government did not have this overview. This again had to do with non-transparent contracts. After a thorough investigation it became clear the city had outsourced nearly 250 services.

Whenever the private sector denies responsibility, the public sector has to step up and is thus forced to carry the biggest risks and costs

After having calculated the costs of each outsourced contract, Barcelona in Comu established the ethical, social and environmental goals which the municipal services need to attain. It was thereupon decided that returning the funeral services back into public ownership would be one of the priorities. Financial consequences were of course also taken into consideration. How much would it cost to bring the employees of the waste services into the public sector with its better pay and working conditions? What are the consequences for the workers? All these calculations must be done. One needs to be prepared before going into the fight for remunicipalisation. The other side never intends to give up easily.

How can unions partake in these people driven strategies?

Public sector workers are frontline in providing services to communities. It is what motivates them. More often than not, they are also members of those very same communities. It means they can look at public services from the perspective of both the producer and the user. Their participation is therefore critically important. Open minded unions can win big victories by engaging the community into the fight for better public services. Re-municipalisation is never just about good working conditions. It is about strengthening the community. Trade unions need to deliver the message that they are protecting public services because people need them on a day to day basis.

There are many good examples of this social or community unionism. In countries like Canada, Norway, Italy and Uruguay, trade unions contributed to or even assumed leadership of re-municipalisation campaigns. In Columbia, we see trade unions of public water companies voluntarily helping out communities that are forgotten by the state. These kinds of dynamics demonstrate that public sector workers and citizens have a shared interest in the provision of universal and affordable services. Almost all successful struggles against privatisation were made possible by strong coalitions between citizens and workers. The-remunicipalisation of the water company in Jakarta, Indonesia and Lagos, Nigeria are cases in point. We need more victories like these. They are well covered by the national media and inspire people in other parts of the countries into action.

Public ownership is not automatically transparent but it is a crucial precondition for democratic public services

There are of course huge differences between sectors and countries in terms of union density, wages and working conditions. Workers negatively impacted by liberalisation, for instance in healthcare, are generally more supportive for re-municipalisation. The situation is different in the utility sector where trade unions often maintained strong footholds. Remunicipalisation may not be a priority for unions that already secured good working conditions. Ownership change inevitably brings loads of stress and uncertainty for workers. It is understandable that workers who once transferred from the public sector to the private sector don’t feel like going through that process again. That’s why the city of Barcelona actively involves trade unions and workers in the transition plans from the outset. Real dialogue is essential to get the workers on board and allow for a socially just re-municipalisation.

Why is so important for TNI to collaborate with unions?

Working with trade unions and community organisations is very empowering. Trade unions can create spaces for discussion among members around concrete and local issues. Our research would not be possible without the assistance of trade unions because of their knowledge of remunicipalisation cases. Focussing on the local level, however, is not enough. We need to be able to present a big, long term picture of how public services can be reinforced for the benefit of future generations. That is why we need to bring our local experiences together in a universal narrative about the kind of society and public services we want to have. This is essentially what we will continue to do in the coming years.

What are the future plans of TNI?

-municipalisation can be seen as very technical. It is about ownership structure, finance, labour, information systems and many other aspects. But it is never merely just technical. On the contrary, it can create a window of opportunity for experiments to renew public values. Many cities in Spain seek a way to tender out the contract to local, non-profit organisations instead of profit driven companies. This broadens our definition of public services. Citizens and workers want to be part of the solution to design better, more ambitious, and more accountable public services beyond those that we already know.

Very technical matters can become very thrilling and exiting when you broaden the discussion to the kind of society we want. We will write new narratives. Remunicipalisation is a viable strategy for a socially just energy transition that puts people, not profits, first. Local authorities and citizens are taking back democratic control of their energy provision in many countries. Cities are emerging as a space for transformative changes to achieve social and environmental justice. I believe new narratives and experiences on the ground empower more people and communities when they are connected on a theoretical and political level. Here at TNI, we are resolved to foster those connections between movements and struggles through our research.