Why are female artists underrepresented?

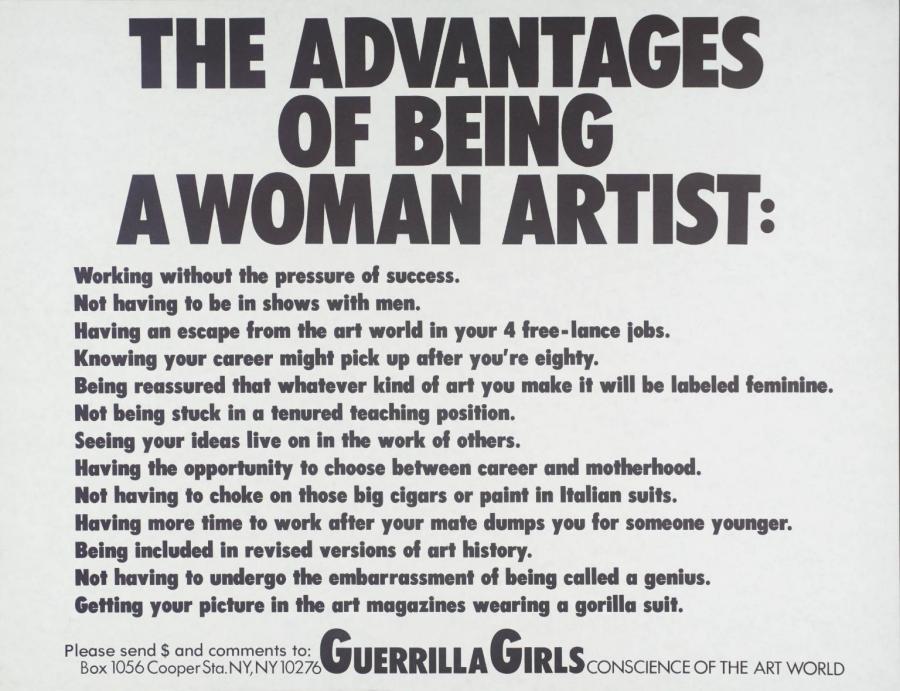

The underrepresentation of female artists is not a new topic. The issue has been raised many times before. In 1984 for instance, a group of anonymous American female artists, known as the Guerrilla Girls, created a range of activist posters. The formation of the group was created in response to the 'International Survey of Painting and Sculpture' in 1984 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This exhibition included work of 169 artists, less than ten percent of whom were women (Manchester, 2004).

"She has the talent of a man"

This is not an exception. Museums such as the Louvre, MoMa, MET, the Rijksmuseum and the Hermitage all house artwork from the most famous and appreciated artists to ever exist. Visitors tolerate long queues and expensive entrance tickets to see DaVinci, Picasso, Van Gogh, Renoir, Warhol, Botticelli or Rembrandt in real life.

Attentive readers will notice that these artists are all male. Are all recognized artists coincidentally male? Are women just not capable of being great artists? Or were women disadvantaged in the world of art history? Listing as many female acclaimed artists as male acclaimed artists is nearly impossible.

The underrepresentation of female artists

The Guerrilla girls did not believe that the unequal representation of women in art history was a coincidence. They wanted to expose sexual discrimination in the world of art, and they referred to themselves as ‘the conscience of the art world’ (Manchester, 2004).

"Are all recognized artists coincidentally male? Are women just not capable of being great artists? Or were women disadvantaged in the world of art history?"

Before discussing why women are underrepresented in art history, two things are important to mention.

First, art is not created in a vacuum. The philosopher Kant argued that art is autonomous and self-contained: l’art pour l’art. He thought that art is solely created to be ‘art’ and nothing more (Haskins, 1989). However, this point of view was heavily criticised and today it is usually assumed that art is not autonomous but reflects and influences society. In ‘Ways Of Seeing,’ Berger (1972) argues that: “Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognizes before it can speak.”In this way, art can influence the way we look at society and people.

Second, gender inequality in art is not a new topic, but a recurring issue. In 1858, an article on female artists was published in the Westminster Review (Guhl, 1858). A century later, Linda Nochlin wrote the famous essay ‘why have there been no great women artists?’ and in 1984 the above mentioned 'Guerrilla Girls' arose (Manchester, 2004).

Despite numerous publications on gender inequality in the arts, there is still limited attention towards female artists. Answering the central question of this article is therefore not an easy one, because the question creates a chain of assumptions and other questions such as: what is the nature of art? When is art excellent? What are human abilities? What is human excellence? What role does social order play in this (Nochlin, 1978)? If it’s true that art reflects and influences society, what does the male domination of art history say about the way we look at women?

Because of the complicated nature of this issue, this article will only focus on two different reasons that have caused female underrepresentation in art history: the way in which art history is written, and the position women held in the 18th, 19th and 20th century. Of course, these reasons are not self-contained but heavily intertwined.

His story of art

Art history is not a fixed fact but manufactured by human beings. In this sense, history (of any kind) is never a neutral activity (Hatt, 2017). During the Renaissance, female artists were seen as the embodiment of the Renaissance-ideal: they were well-educated and aristocratic. Halbertsma (2018) argued that these female artists were mentioned in the 16th century as artists, but fell into oblivion in the 18th century due to two causes.

First, there was a large emphasis on stylistic changes within art history. These stylistic changes were per definition performed by men. Male artists were given the freedom to experiment (which could lead to stylistic changes) while female artists were expected only to paint ‘homely’ scenes. Consequently, the less-known artists (usually females) were written out of the artistic manuals (Halbertsma, 2018).

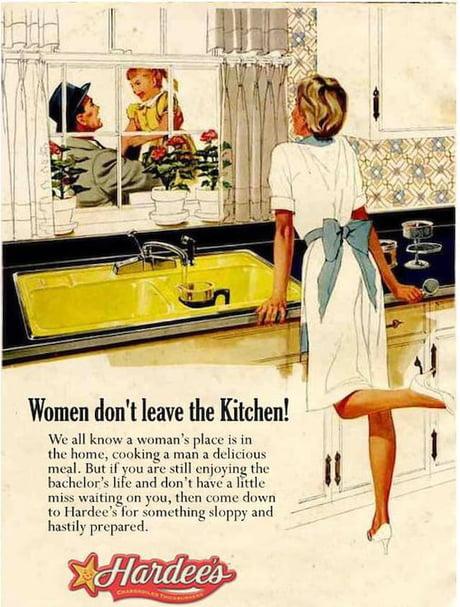

Second, the idea that woman should only be concerned with domestic tasks and motherhood dominated the 18th century. This trend continued in the 19th century (Bavelaar, 2018). In the 19th century, when art history was acknowledged as a science, the canon of art history was written. During this period, the position of women was subordinate. As a consequence, women were not perceived as possible great artists and thus not incorporated in the history of art.

"Art history is not a fixed fact but manufactured by human beings"

Not only were women excluded from the canon of art history, they also were excluded from art itself. Even though making art is often perceived as a free and autonomous activity, the opposite seems to be true. According to Nochlin (1988), art making occurs in a social situation, in social structures, and is determined by institutions like art academies. She also argues that it was made institutionally impossible for women to achieve artist’s excellence and success on the same footing as men, no matter the level of their talent.

In her essay ‘why have there been no great women artists?’ Nochlin explains different exclusion mechanisms, which were present in the art sector and society itself.

First, women were not allowed in art-guilds and academies. The exclusion from such institutions for multiple centuries had led to women being "deprived of the possibility of creating major art works’" (Harris, 2001).

Second, in the 16th, 17th and 18th century, history painting was most recognized. As mentioned before, women were not expected to concern themselves with these subjects. Another exclusion mechanism Nochlin mentioned was the exclusion from nude drawing. Women were not allowed to draw and paint with nude models as an example. Being able to paint anatomically correct bodies is indispensable when it comes to painting mythological, biblical and historical scenes (Nochlin, 1978). A final exclusion mechanism concerns the tasks females were appointed in the 18th and 19th century.

Women were not encouraged to pursue a professional career (Nochlin, 1978). On the contrary, they had to occupy themselves with domestic tasks and motherhood. Thus: the social, cultural and practical conditions for women to be artists were not present in the 18th and 19th century and consequently they were not included in the history of art.

Fig 1: Poster made by the Guerrilla Girls in 1985

Social, cultural and practical barriers

The second reason for the underrepresentation of females in art history has to do with three broad concepts: patriarchies, structures and stereotypes. Western societies are usually dominated by ideas embedded in patriarchies. A patriarchy can be defined as ‘a form of social organization in which men have more power and dominate other genders.’

This organisational form favours men and encourages the idea that one gender is natively better then others. Patriarchal societies have developed and mutated in relation to changing economic and political circumstances (Harris, 2001). Since the 19th century, the male bourgeoisie has been the predominant social and sexual class. When looking at the history of art, it is thus critical to see the relations between structures of artworks and the elements of the broader social structure within which art is produced (Harris, 2001).

In a patriarchal society there is an imbalance regarding power distribution. Hierarchical relations of power between women and men tend to disadvantage women. These gender hierarchies are often perceived as natural but are rather socially determined and are subject to change over time. They can be seen in a range of gendered practices, such as the division of labour, resources, gendered ideologies and ideas of acceptable behaviour for women and men (Reeves and Baden, 2000).

"Hierarchical relations of power between women and men tend to disadvantage women"

Ideas about acceptable behaviour can be seen as 'structures.' In the late 19th century, philosophers emphasised the power of these structures. The behaviour of individuals and groups were explained through existing social, economical and political structures. In his essay ‘Structure, Habitus, Practices, philosopher Pierre Bourdieu (1980) argued that power is culturally and symbolically created and constantly reinforced through the interplay of agency and structures. This is done by the habitus.

Bourdieau explains habitus as: “the socialized norms or tendencies that guide behaviour and thinking. It influences the identity, actions and choices of the individual” (Bourdieau, 1980). These structures are extremely persistent. The idea that men are able to create masterpieces and women should occupy themselves with domestic tasks could be a structure that is still present in today’s society.

This corresponds with the “If I haven't dusted the furniture and made the beds do I have the right to begin carving?-syndrome” by Jane Piirto. She argues that the profession of an artist demands extraordinary commitments in terms of willingness to take rejection, to live in poverty, and to be field independent. Those are traits (expected behaviour) of committed males but not of committed females, who usually choose careers as art educators, not as artists. Girls who aspire to be an artist have to reconcile their ambition with the stereotypical gender roles of a nurturing, recessive, motherly female with that of the stereotypical unconventional artist (Piirto, 2000).

Fig. 2: A commercial from the mid 20th century showing gender roles at that time

Another important concept when discussing the reasons behind the lack of female artists is 'stereotypes’ and more specifically ‘gender stereotypes.’ Heilman (2012) explained that stereotypes are generalizations about groups that are applied to individual group members, simply because they belong to that group. Gender stereotypes are generalizations about the attributes of men and women.

Gender stereotypes have both descriptive and prescriptive properties: descriptive gender stereotypes label what women and men are like while prescriptive gender stereotypes label what women and men should be like. She argues that descriptive and prescriptive gender stereotypes can compromise a woman’s career progress (Heilman, 2012).

This happened in the 18th and 19th century, when women were expected to be a mother and to not pursue a career. Because of persistent structures explained by Bourdieau (1980), these gender stereotypes are maintained. It can thus be argued that the underrepresentation of female artists has to do with persistent gender roles and solidified structures in a mostly patriarchal society, which affects the norms and values people behave towards.

In other words: uncompromising existing structures and traditional attitudes from the 18th, 19th century and 20th century regarding gender roles could explain the reason why women are still underrepresented in the world of art. However, recent cross-sectional studies have shown that there are changes visible over time towards greater egalitarianism and less gender differentiation (Haines et al, 2016). This could mean that people’s views of gender roles are slowly shifting.

"Descriptive and prescriptive gender stereotypes can compromise a woman’s career progress"

Tip of the iceberg

This article focussed on two reasons why females are underrepresented in the world of art. The first reason involved the way art history was written and art history itself. Women were not given the chance to develop themselves as artists, and consequently they were not mentioned in art history books. While this reason seems to be literally history and of a passing nature, the second reason is more profound. Because of ever-present structures regarding gender roles, women sometimes struggle to overcome the gender barriers theyface. Ideas about gender roles, which dominated the patriarchal society in the past centuries, are still present through social, political and economic structures. This means that a possible solution lies within a change in structure and culture. Perhaps this change is already in motion since the cross-sectional study by Haines et al. (2016) showed a little progress towards greater egalitarianism and less gender differentiation.

Because this article only targeted the two above-mentioned reasons, it is important to bear in mind that these reasons are only the tip of the iceberg. Gender inequality in arts extends much further than this article discusses. Topics like feminist art and the large amount of naked women portrayed in paintings are other examples of the far-reaching issues regarding gender inequality in arts. Further research on these topics could contribute to closing the inequality gap in the world of arts.

References

Bavelaar, H. (December 14, 2017). Bronnen en Methoden in de Moderne Hedendaagse Kunst (College slides).

Berger, J. (1972). Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Classics.

Bourdieu, P. (1980). Structure, Habitus, Practices in The Logic of Practice. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Haines, Elizabeth., Deaux, K., Lofaro, N. (2016). The Times They Are a-Changing…Or Are They Not? A Comparison of Gender Stereotypes, 1983-2014, Psychology of Women 1, (11). doi:10.1177/0361684316634081.

Halbertsma, M. (2007). The call of the canon. Why art history cannot do without. Making Art History: A changing Discipline and Its Institutions. New York: Routledge: 16-31.

Haskins, C. (1989). Kant And The Autonomy of Art. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 1. (47), pp. 43-54. Doi: 10.2307/431992.

Hatt, M., Klonk, C. (2006). Art History: A Critical Introduction to Its Methods. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Harris, J. (2001). The New Art History: A Critical Introduction. Londen: Routledge.

Heilman, M. (2012). Gender Stereotypes and Workplace Bias. Research in Organizational Behaviour, 32, pp. 113-135.

Manchester, E. (2004, December). Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into The Met Museum?

Nochlin, L. (1988). Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? In: Women, Art and Power. (pp.145-178). New York: Harper and Row.

Piiero, J. (2000). Why Are There So Few? (Creative Women: Visual Artists, Mathematicians, Scientists, Musicians).

Reeves, H., Baden, S. (2000). Gender and Development: Concepts and Definitions, 55. Brighton, England: BRIDGE, Institute of Developmental Studies, University of Sussex.