Why you should go see Black Panther this February

At times it can feel like all that theaters are playing these days are superhero movies. This year alone we were offered Thor: Ragnarok, Wonder Woman, Logan, Justice League, Power Rangers, a second Guardians of the Galaxy movie, and even a Lego Batman Movie. As a layman in the genre, these movies can look quite alike to me. And so I was not particularly stoked to see the announcement for yet another one when it came out this summer. But the trailer for Black Panther was different.

It hooked me right away with its bold visuals and its unapologetic African outlook. This is more than just a superhero movie with a black protagonist, it seems to be a black vision of both the past and the future of a people and a culture. And it is not the only narrative to do so. In fact, there have been a number of very popular projects that have used similar strategies in the last couple of years. In this paper, I propose that Black Panther should be understood as a manifestation of a current revival of Afrofuturism.

What is ‘Afrofuturism’?

It is not easy to define Afrofuturism, it seems to be a term that can be appropriated in different ways depending on the need one has for the concept. Often, it is understood as a subgenre of science fiction – a lot of work that could be considered afrofuturistic is also called ‘black science fiction’ or ‘black speculative fiction’. Afrofuturism combines the conventions and aesthetic of sci-fi with themes and concerns of the African diaspora. So what is being envisioned is a particular segment of the future, that is: the future of black people and black culture. That is also how the Tate museum defines the term:

“Afrofuturism is a cultural aesthetic that combines science-fiction, history and fantasy to explore the African-American experience and aims to connect those from the black diaspora with their forgotten African ancestry.”

However, when the term was first coined it referred to a lot more than merely an ‘aesthetic’. Mark Dery, who introduced the word in his essay ‘Black to the Future’ in 1993 attributed it a definite political potential. Dery proposed the term for a trend he had noticed in black art in the 80s and 90s: more and more, they included futuristic references and an emphasis on digitalization and technology. He found traces of it in the paintings of Jean-Michel Basquiat (see image below), in the scratching on the records of dj Grand Master Flash, in Lizzie Borden’s movie Born in Flames, in George Clinton’s debut album Computer Games.

Jean-Michel Basquiat “Molasses” (1983)

Up until Dery’s text, an African approach to science fiction was more broadly understood as an aesthetic point of view, rather striking due to its mix of robots, electronic sounds, tribal motifs and shining metallic. But Dery pointed out that this point of view was inherently a political one:

“The notion of Afrofuturism gives rise to a troubling antinomy: can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?”

So Afrofuturism always stands on two legs: one leg in the past, relating to the diaspora and connected to notions of alienation and estrangement, and one leg in the future, in trying to envision a utopic future.

Sun Ra’s early Afrofuturism

In retrospect, this dilemma can be found in earlier expressions of Afrofuturism too. The most common point of origin are the works of jazz musician and philosopher Sun Ra. Considering the following TV performance of Sun Ra in 1989, we can recognize the elements that still form the backbone of Afrofuturism today:

The aspect that may catch your attention first is Sun Ra’s flamboyant costume which includes a pyramid hat that gives him the looks of an Egyptian high priest. The Egyptian outfit brings in a reference to a North-African past, a vague waving towards a past that seems more mythical than factual. At the same time, the mention of ‘the wisdom of the planets and the stars’ and the extraterrestrial look of his sparkling outfit points towards a future, one that is just as vague and mythical as the Egyptian dress. Sun Ra combines the past and the future in his presentation, with little regard for historical accuracy. But how could Sun Ra present an accurate presentation of his historical roots? The African history has continuously been re-written or erased by others, that is: if it even was archived like the white western tradition has been. So the only way to tell the story of the past is to combine fact and fiction, to bring in the imagination where records don’t suffice. For Sun Ra, both his culture’s history and its future are undefined and therefore equally fantastic.

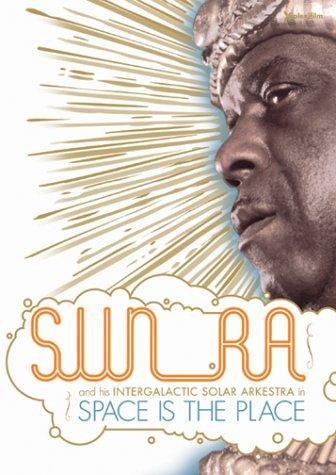

In between this mythical past and the fantastical future, we find the present. The temporal reality of Sun Ra himself, which was as uncertain as his past or future. In the 1974 movie Space is the Place, Sun Ra says:

“I’m not real, I’m just like you. You don’t exist in this society. If you did, your people wouldn’t be seeking equal rights. You’re not real. If you were, you’d have some status among the nations of the world. I do not come to you as a reality, I come to you as a myth because that’s what black people are: myths. I come from a dream that the black man dreamed long ago. I’m actually a presence sent to you from your ancestors.”

Space is the Place (1974)

To be unacknowledged and to be considered invisible effectively deprives one of one’s existence, renders one ‘unreal’. Sun Ra emphasized that he was unreal, because he knew that his presence did not matter. This question still features prominently in the news today, when we see demonstrators holding up signs to remind us of the fact that Black Lives Matter. Think also about the use of the signal ‘No Human Involved’ that white police officers used after attacking Rodney King in 1992. In this context, it is not hard to see why Sun Ra would identify with the figure of an alien – his people have been dehumanized and alienated throughout history. The extravagant outfit is a bitter emphasis of the fact that it would not matter whether he wears a normal suit and tie or dresses up as an extraterrestrial figure, it would not affect his status in the culture he lives in.

The story is further troubled because the flamboyant way with which Sun Ra expresses this fantasy makes him appear rather comical at first glance, and this is indicative of the kind of split story that Afrofuturist works portray: on the one hand there is a very entertaining performance to be enjoyed (the sparkling glitters, the funky great music, the bright colors) while at the same time, these performances tell stories that are based on a collective pain and trauma that is very real. In this context, when one is uncertain of their past and threatened in their presence, it can be a powerful act to paint the vision of a black future. Media studies scholar Nana Adusei-Poku explains that black citizens can feel:

“erased from the past, erased from the future, and you’re hovering in the here and now, waiting for someone to write a story with our complexion in it (…) Afrofuturism allows black people to see our lives more fully than the present allows – emotionally, technologically, temporally and politically.”

Adusei-Poku points out that from this position, it can be subversive to claim a vision of the future at all, because to deny your opponent a future is one of the most effective ways to deny them a presence now. How often do we not see political speech referred to opponents as ‘backward’? Whether it is the alt-right movement wanting to ‘Make America Great Again’, or Islamic interpretations of women’s dress codes – they are referred to as conservative, as something from the past, as something that has no place in the future. In an act of rebellion, a culture that is accused of lacking civilization claims the creativity to shape its own future.

And so Afrofuturism answers to a desire to know where one comes from, so that one can claim a full status in the present, and to envision where one is going. Afrofuturism creates all of this.

Afrofuturism 2.0

Sun Ra’s approach to Afrofuturism admittedly looks rather dated, but Afrofuturism is not a thing from the past. As recent as 2013 Alondra Nelson and Reynaldo Anderson, two important scholars working on this topic, have proclaimed that we are currently in a second phase of Afrofuturism. Two years later, they published their book ‘Afrofuturism 2.0 The Rise of Astro-Blackness’. Like Dery in 1993, the authors see an influx of Afrofuturism in contemporary culture. And after a moment of reflection, I am sure that you will be able to find some examples yourself.

How about Beyoncé Knowles’ reflections on African traditions in her Lemonade album (2016). The most discussed instance is perhaps her video for Hold up, in which Beyoncé references a variety of traditional African symbols.

In this clip, Beyoncé is dressed as the African goddess Oshun: with a golden-yellow dress with golden jewelry. Oshun is one of the divine figures (orisha's) of the Yoruba people, from the Southwestern regions of Nigeria. As the only female original orisha, she is a figure of femeninity and sensuality. She is also connected to the water in her many forms: both as a source of life and as a destructive force. Hold up starts with Beyoncé stepping out of the water that births her. Water is an important symbol in the African diaspora that can have many meanings: it can refer to the water that was crossed when the enslaved people were transported from the African continent, or to the water that washes away the history of the people. At the same time, water is the source of all life, it refreshes us and washes away human sin. She stood at the cradle of huiman life, but when she is angered she can produce outbursts that destroy all in her way. Beyoncé dances Oshun’s act of hysterical laughter while she unleashes her anger on the world (or the man) that has hurt her.

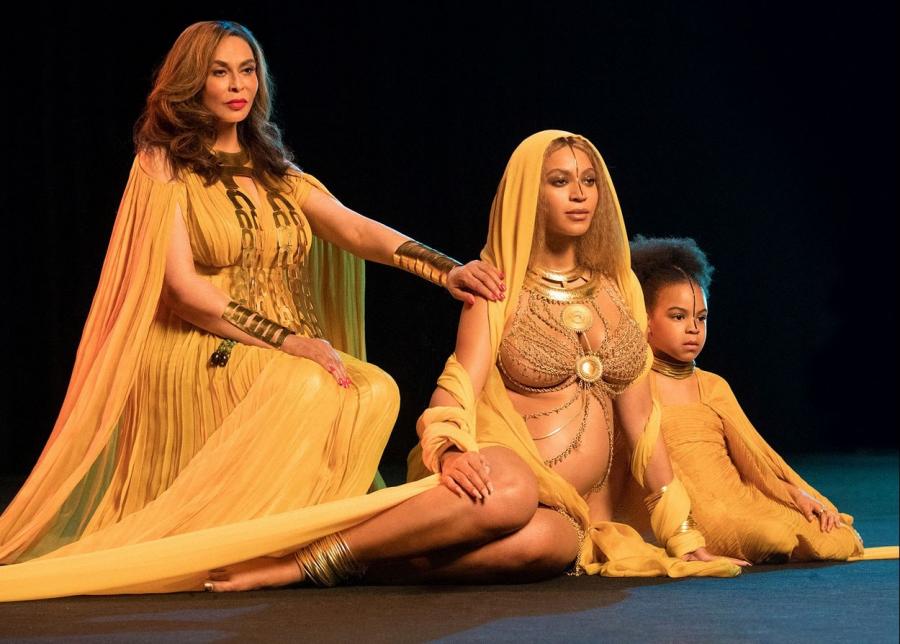

Three generations of Knowles women

In another instance, Beyoncé performed the 2017 Grammys by showing off her pregnant belly and wearing a similar Oshun costume and religious imagery. Accompanied by poetry of Somali writer Warsan Shire the performance was a mixture of mythology, religious symbolism, and African imagery, culminating in a vision of three generations of Knowles women: mother Tina, Beyoncé, and her daughter Blue Ivy. The past, present, and future of a black female line staring us down majestically. And of course, she had a similar vibe in her 2015 Grammys performance, where she was a galactic goddess in a white cape. A vision that mirrored her sister Solange Knowles’ Saturday Night Live performance in November 2016.

Beyoncé at the Grammys 2015

Solange at SNL

A more explicitly involved example is Janelle Monáe’s Metropolis project. This popular RnB singer proclaimed herself to be an android after being introduced to the concept by her colleagues in the Wondaland Arts Collective. Her works reflect her interest in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and the novels of Isaac Asimov and Octavia E Butler. Much like Sun Ra, she uses sci-fi as an allegory for the African-American experience. In an interview with The guardian, she explains:

"The android represents a new form of the Other. And I believe we're going to be living in a world of androids by 2029. How will we all get along? Will we treat the android humanely? What type of society will it be when we're integrated? I've felt like the Other at certain points in my life. I felt like it was a universal language that we could all understand.”

In her conceptual series Metropolis, she tells the story of her alter ego Cindi Maryweather, an android who is created in 2719 for a general market. In her upbeat pop songs, Monáe includes refrences ot both the past, the present, and a vision of the future of black people. Most jarring is perhaps her video for Many Moons she envisions the futuristic market in which the black android/human of the future would be sold:

Black Panther: An Afrofuturist superhero

This is the context in which the new Black Panther should be understood, and these are the artists that form the company of creators Ryan Coogler and Joe Robert Cole. This might seem a bold statement. After all, the movie isn't even out yet. But of course we already know quite a lot about the narrative of Black Panther via his appearances in multiple Marvel comics and several of their animated series. Although Black Panther isnt Marvel’s first leading super hero of color (Blade was an important precurser in terms of cinematic live action), he was one of the first Black superheroes in mainstream American comics when he first appeared in 1966. However, there is more to the story than just him being black. From what we already know about his character, he embodies a vision of both a black past and a black future.

Black Panther’s alter ego T’Challa is the freshly installed king of the African country of Wakanda. (We have seen his transition into power in the 2016 Captain America movie Civil War.) In addition to this regal position, T’Challa gets his superhero powers from the Panther God Bast. Bast is an ancient god who is imbued with a life-giving solar heat by his divine interactions with the Egyptian god Ra. T’Challa is therefore connected to several strands of Black authoritative traditions: the royal family of Wakanda and a long line of African divinities. As such, he is connected to the earliest traditions of African culture.

What is more, Wakanda might be portrayed as an explicitly African nation, but it does not adhere to the stereotypical Western imagery of a simple and technologically challenged environment. Rather, Wakanda as a country is scientifically further advanced than any contemporary Western nation. The country protects its technological knowledge by isolating itself from the world, while all the while curating its electronic secrets and developing computer systems that are impervious to attacks from other realms. Black Panther is therefore an example of a sub-genre of fiction in which Africans display a prowess and understanding of technological and scientific advancement. It paints a picture of a black future, and the success of the curation of black intellect and knowledge via technological developments. In a piece written for Comics Alliance, Aaron Reese wrote:

“In establishing Wakanda Marvel strayed away from the usual “primitive” and “wild” tropes associated with Africa, as seen in books like Tarzan, creating a self-sustaining, futuristic power-house that never felt the effects of colonialism or white imperialism. Wakanda shines as mecca built on technology and magic, without a trace of poverty or disease.”

Wakanda

This is examplified by the language used by T'Challa. In an interview with CNET, actor Chadwick Boseman explains how he developed his accent for this role:

"Colonialism in Africa would have it that, in order to be a ruler, his education comes from Europe. I wanted to be completely sure that we didn't convey that idea because that would be counter to everything that Wakanda is about. It's supposed to be the most technologically advanced nation on the planet. If it's supposed to not have been conquered -- which means that advancement has happened without colonialism tainting it, poisoning the well of it, without stopping it or disrupting it -- then there's no way he would speak with a European accent. If I did that, I would be conveying a white supremacist idea of what being educated is and what being royal or presidential is. Because it's not just about him running around fighting. He's the ruler of a nation. And if he's the ruler of a nation, he has to speak to his people. He has to galvanize his people. And there's no way I could speak to my people, who have never been conquered by Europeans, with a European voice."

Via the language spoken, the movie already indicates its Afrofurturist agenda. It indicates a re-enivisioning of Africa's past, an Africa that has not been colonized and made to sound like its opressores. And it claims for itself a reality of a non-White, all-African society that is technologically superior to those nations that in fact did invade the continent.

And this is how we should welcome Black Panther next year: as a vision of a black past and a black future, the latest arrival of a contemporary mainstream Afrofuturist narrative. And something to be very excited about.

Black Panther will be in theaters in the Netherlands from 14 February 2018.