A Nation of Immigrants or a Nation of Laws?

On August 7, 2019, 680 workers at multiple chicken processing plants in rural Mississippi, were detained in a raid coordinated by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Homeland Security Investigations, and the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District (SD) of Mississippi. It was the largest-single state worksite raid in U.S. history, a fact that was touted by press releases and public addresses after the detentions, particularly by the U.S. Attorney for the SD of Mississippi, Michael Hurst.

Noting the symbolic messaging embedded in the raid, former ICE Director John Sandweg said in an interview that, "...candidly, you know, bringing 600 agents in to make 600 arrests is done with the media in mind." Images of searches and arrests of Latino workers, contrasted with news coverage showing the young, weeping children of the factory workers, some of whom were stranded at schools when their parents could not come to get them.

For many, the images of the children were yet more evidence of the cruelty of immigration policy under the Trump administration. Still, the message was clear, the American government was throwing its full weight behind finding and removing immigrants who did not have permission to stay in the country - no matter how hard working or law abiding.

As a sort of spokesperson for the raids, U.S. Attorney Michael Hurst was legalistic in his messaging, framing the arrests of the immigrant factory workers as a simple matter of exacting accountability from "those who violate our laws". Underscoring this point, he said "Now, while we are a nation of immigrants, more than that, we are first and foremost a nation of laws." The use of "first and foremost" in the phrase distinguished it from most other versions of the expression.

Usually the phrase is delivered with "but" as qualifier, as in "Yes, America is a nation of immigrants, but, it is also a nation of laws". This particular form of the device has a long history in U.S. immigration politics. It has been used by both Democratic and Republican presidents in describing legislative action to address the problem of unauthorized immigration in the U.S. Before Hurst's statement, nearly verbatim versions of the trope were used by Presidents Trump, Obama, Clinton, and G.W. Bush.

The change signals a turn away from immigration as an American value, specifically among Donald Trump and his supporters.

Thus, the phrase has invoked bi-partisan - indeed "American" - values on immigration, while making two distinct claims about American exceptionalism. The inclusion of "but" suggests that in relation to unauthorized immigration, the laws must be prioritized such that an ideal about the U.S. as welcoming to immigrants cannot apply to those who stay illegally. Still, the bi-partisan construction at least hints at recognition of the ways that "nation of immigrants" and "nation of laws" have been discursively, ideologically, and legalistically in tension with one another.

Hurst's "first and foremost a nation of laws" dismisses this tension altogether, and signals a turn away from immigration as an American value, specifically among Donald Trump and his supporters. In fact, this rejection of America as a nation of immigrants was officially affirmed in February of 2018 when the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration removed "nation of immigrants" from their mission statement. The statement had previously read: "USCIS secures America's promise as a nation of immigrants by providing accurate and useful information to our customers, granting immigration and citizenship benefits, promoting an awareness and understanding of citizenship, and ensuring the integrity of our immigration system."

A Nation of Immigrants

The idea of America as "a nation of immigrants" is a uniquely American proclamation. The phrase does say something accurate about the centrality of foreigners in the nation's formation and America's long history of immigration, even as it invisibilizes Native Americans in that history. Yet America as "a nation of immigrants" claims an exceptionalism that is not totally warranted. Contrast United Arab Emirates 80%+ foreign-born population, or even neighboring Canada's current 22%, to America's 14% foreign-born population (it has never been more than 15%). Of course, the phrase is not supposed to point simply to demographics. In its contemporary use the phrase has a sort of poetic gravity about it. Like the Statue of Liberty, the phrase stands for America as a beacon that has drawn people from all over the world and from all walks of life.

Although today "nation of immigrants" is a pro-immigrant declaration, Gabaccia (Donna, 2010) shows that the phrase was initially used to justify the exclusion of immigrants, not to celebrate their inclusion. According to Gabaccia, "emigrant" was the more common, more neutral, term for the foreign-born, before U.S. immigration began to reach the levels that it did throughout the mid-19th century and early 20th century.

The phrase "nation of immigrants" was initially used to justify the exclusion of immigrants, not to celebrate their inclusion.

"Immigrant", instead, had a negative connotation and Gabbaccia documents how the switch in common usage from "emigrant" to "immigrant" was well in place by 1920 when powerful anti-immigrant movements had taken hold, leading to some of the most restrictive immigration policies in the nation's history. Given that "immigrant" had critical undertones, its place in the phrase "nation of immigrants" did not then have the sort of positive and U.S. exceptionalism connotations that it does now. As Gabaccia argues, when the phrase arrived on the scene in the late 19th century, it was loaded and its meaning varied regionally.

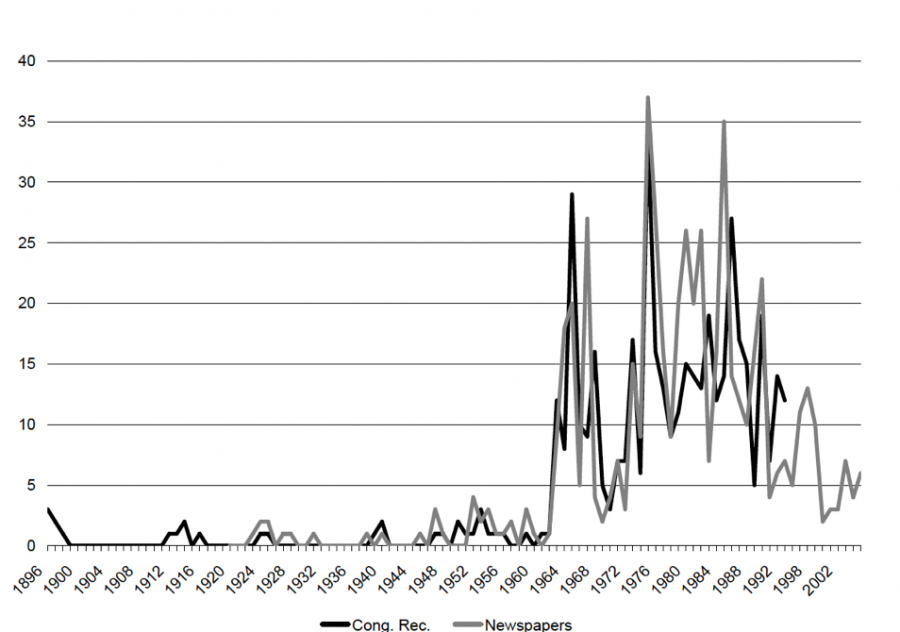

In short, Gabaccia views the adoption of the metaphorical phrase as gradual, nudged along by evolving notions within the U.S. about nation-building, and who belonged to the American nation. As can be seen in Figure 1, from Gabaccia's paper, the use of the phrase - its more idealistic variant - ballooned at the point when the U.S. was about to adopt civil rights era immigration legislation that eliminated immigration quotas favoring European immigration to the U.S.

Figure 1. Use of “Nation of Immigrants” in Digitized Newspapers and the Congressional Record, 1896–2005. Source: Gabaccia, R. D. (2010). Nations of immigrants: Do words matter? The Pluralist, 5(3), 5-31.

A Nation of Laws

The idea of America as a "nation of laws" has its roots in the very founding of the nation and the formulation of the U.S. Constitution. Historians would point to the fact that America actually inherited the idea of "the rule of law" from the English themselves, who, in the eyes of American colonists had turned away from a legal principle going back to the Magna Carta. To be a "nation of laws", then, means that through the primacy of laws America would thwart the tyranny of the ruling few.

As the logic goes, while men are partial, laws are impartial. Thus the "rule of law" carries with it a sense of all being equal before the law: "No one is above the law". While this logic is countered by the many ways that laws have been partially applied in the U.S., for example along racial lines, the idea of America as a "a nation of laws" is particularly triumphalist and perhaps even outward-facing in a way that "a nation of immigrants" is not.

"Nation of laws" forwards the notion the legal and political systems are impartial, that immigration laws are designed to be impartial and must be consistently and faithfully applied.

Since its founding, America has had no history of autocracy and has had a lasting, largely unchallenged constitution. Thus, for proponents of America as a "nation of laws", the U.S. stands like few other countries in the world, and indeed in history. "Nation of laws" is outward-facing, then, in that it asserts a privileged standing among the world's democracies. "Nation of immigrants", in contrast, has been primarily inward-facing, reflecting and shaping narratives about national belonging and citizenship.

"Nation of laws" forwards the notion that America's legal and political systems are impartial, and therefore, that its immigration laws are designed to be impartial and must be consistently and faithfully applied. However, its use by politicians to defend anti-immigrant policies masks the ways that the U.S. immigration system has deeply embedded inequities and contradictions. Scholars and critics of U.S. immigration policy - see for example, Aviva Chomsky's (2015) Undocumented: How Immigration Became Illegal - note that the U.S. government passed or dismantled laws that not only created the problem of unauthorized immigration, but actually worsened it through successive immigration control laws.

Nation of immigrants, Nation of Laws and a Polarized America

While "nation of immigrants, nation of laws" has primarily been used over the past 20-30 years in relation to unauthorized immigration, current federal policy moves to curtail legal immigration demands a careful reading of the trope's deployment in political discourse. Current debates about immigration in the U.S. are unfolding in the context of disruptive polarization, such that in the U.S. a person's views about immigration are highly correlated with political identification. This is quite different from the climate in the 1990s, when anxieties about unauthorized immigration were at fever pitch.

Today, 62% of Americans say that immigration strengthens the U.S., an opinion that is split along party lines, with 83% of Democrats saying that immigrants are a strength, and only 38% of Republicans agreeing. While a majority of Americans view immigration as a strength, this is a complete reversal of public opinion on immigration 20 years ago. In 1994, 63% of Americans said immigrants were a burden to the U.S., and Democrats and Republicans did not differ in their opinions on this.

Those who deliver the phrase for political effect may have very different audiences - indeed, quite different "Americas" - in mind when they invoke it.

Consequently, when "nation of immigrants, nation of laws" is uttered today, it is in the context of hugely polarized opinions on immigration. It means that the phrase can no longer be assumed to hold the same meaning for all Americans, and that those who deliver it for political effect may have very different audiences - indeed, quite different "Americas" - in mind when they invoke the phrase.

With the American presidential election now in full swing, Democratic presidential candidates hoping to face off against Trump in 2020 have proposed a number of ways to reform the immigration system. Some have sought middle ground positions mindful of how polarizing immigration is.

Presidential candidate Julián Castro has tried to distinguish himself in a crowded Democratic field through his more fully developed immigration reform proposals, which are to the left of most other Democratic candidates'. By naming his platform a "People First Immigration Policy ", Castro directly addresses the forceful turning away from the "nation of immigrants" ideal, towards de-personalized, and de-humanized "rule of law" principles in the execution of Trump's openly anti-immigration agenda. In practical terms, Castro's proposal would decriminalize illegal border crossings and overhaul ICE in ways that would limit the sorts of massive workplace raids that took place in Mississippi.

Symbolically, the "People First" framing used by Castro flips Hurst's version of the "nation of immigrants, nation of laws" trope, communicating instead, "while we are a nation of laws, first and foremost we are a nation of immigrants". Yet it is a message that, in the current U.S. political climate, cannot reconcile the widening political and cultural cleavages in American society in relation to immigration, or otherwise.

References

DONNA, R. G. (2010). Nations of immigrants: Do words matter?. The Pluralist, 5(3), 5-31.