Trumps Tweetopoetics

It has been remarked before: when Donald Trump gives a public speech, the units of his speeches are tweets – or at least: he produces chunks of performed rhetoric that can be effortlessly converted into the format of tweets[1]. Thus we can squeeze an almost unaltered fragment from his speech for the H&K Equipment company in Pittsburgh PA (18 January 2018) into the Twitter box:

speech in a tweet

But at the same time, this fragment of his speech draws from a tweet he posted the day before the speech:

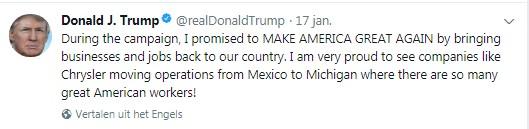

Tweet in a speech

That is the point: Trump’s offline, live discourse has an almost natural spillover quality into his online discourse. Talk is tweet, and tweet is talk.

The tweets are instructional, showing his followers how to speak like Trump.

This, then, grants some of his tweets (the most appealing ones, perhaps) an orally-performable dimension. Put simply, some of his tweets appear as chunks of discourse that can be spoken by others. In fact, they contain lots of pointers as to exactly how they can be delivered in spoken speech. In other words, they are instructional, showing his followers how to speak like Trump. Let us consider an example.

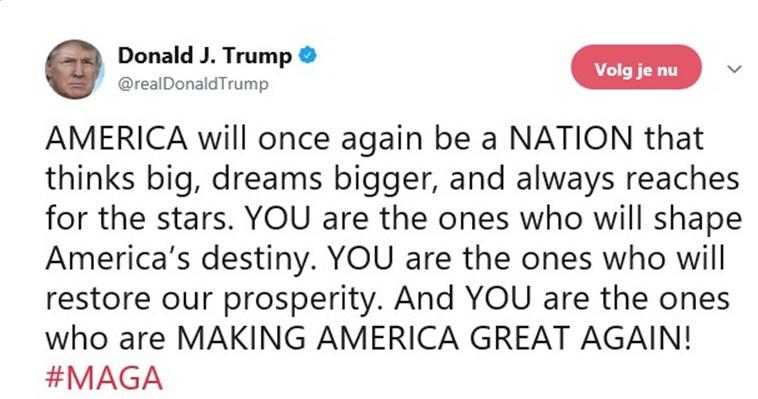

Trump tweet 18 January 2018

Trump posted this tweet on his personal account on 18 January 2018, and it reflects on the same speech in Pittsburgh. The tweet, note, is not a fragment of the speech. In the tweet, we see how he uses upper case for specific words and phrases – a familiar feature for those acquainted with Trump’s tweeting habits. He also uses an exclamation mark at the end of the tweet – once again, a familiar feature. Both features of written discourse, of course, are metapragmatic instructions: they suggest not just content relevance, but they also suggest a way of pronouncing: louder, and with some emphasis.

Talk is tweet, and tweet is talk

But there are more metapragmatic pointers in this tweet, and here we need to turn to what is known as “ethnopoetics” – an analytical technique designed to bring out the implicit structure in spoken discourse[2]. When we transcribe the tweet according to ethnopoetic conventions, we get this.

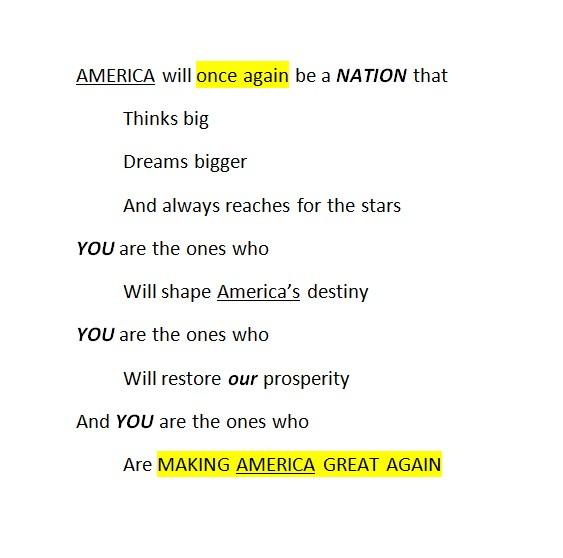

Ethnopoetic transcript of the tweet

We now see that the tweet is replete with different forms of rhyme: several kinds of connections tie parts of the text together into powerful features of performance.

- The tweet opens with “America” (in upper case). This term is repeated twice: once halfway (“shape America’s destiny”), and once in the final (punch) line: “make America great again” (in upper case). America is a central motive.

- The term “again” – the motive of revival, so powerful in Trump’s rhetoric – reoccurs in the opening phrase and the closing phrase, each time connected to “America”. America is new in this text, or, at least, it will be new - hence the use of the future tense.

- The “once again” in the opening line prefigures the “make America great again” of the closing line. Opening and closing are rhetorically connected, they are each other’s echo – hence the highlighting. But the repetition in the closing line is enriched by what precedes – the opening line sets the stage, then comes an argument, after which the opening line is reformulated as the conclusion of the argument. The rhetorical circle is closed.

- So how is this argument organized? In the opening line, “America” is equated with “nation” (also in upper case). What follows is a classical “triplet” – three repetitive lines – in which he qualifies this nation. He does so by “escalation” (again, a well-known rhetorical trick): “big-bigger-reaches for the stars”. “Reaching for the stars” is also semantically connected to “dreaming” in the previous line.

- Next, this “nation” is projected onto the audience: “You” (in upper case) followed by “are the ones who”. The term “you (are the ones who)” is the central structuring device in the middle part of the text. Trump again uses a classical “triplet” here: he organizes “you” in three consecutive, repetitive and structurally similar statements. We get a triple rhyme through the repetition of “YOU are the ones who”.

- You is twice associated with “America” (“America’s destiny” and “making America great again”), and once with “our” in the phrase “our prosperity”. You = us = America.

- Of these three statements, the first two display sound rhyme (destiny, prosperity), while the third one brings the climax: the central slogan of Trump’s campaign and presidency (“make America great again”). Any doubt that this would be the climax is removed by the exclamation mark. So we get: you = us = America = Trump.

This is a pretty fine example of rhetorical craftsmanship, in which literally nothing is out of place. We get a nice piece of poetically structured – and thus affectively appealing – political discourse here. This degree of poetic structuring makes the text performable: the audience gets loads of cues as to how this text should be, and can be, spoken to others. It is also no longer just a one-liner: it is a far more complex argumentative bit of text, driven by strong and very well elaborated images of good-better-best in a new America under Trump. It’s the stuff of persuasive talk.

We are witnessing a new format of public broadcasting here, of presidential spoken discourse.

But we get all of it in a tweet: a typically written genre of online discourse appears to display dense characteristics of spoken discourse. There is just one thing that cannot be extracted from the online to the offline world of speech: the hashtag #MAGA is the unique Twitter-only feature of the tweet. The rest of the text is exportable.

This shows us how the online and the offline rhetorical world of Donald Trump are profoundly connected. We are witnessing a new format of public broadcasting here, of presidential spoken discourse. Not just for contemplation and admiration by his audience, but for active uptake and repeated offline performance. And not the broadcasting of lengthy stretches of text, but of texts that are formatted as tweets – for retweeting as well as for repeating as tweetable speech. Trump referred to Twitter as “his voice”. Through tweets such as these, he enables his followers to imagine his voice as actually heard, and even spoken collectively as a new nation.

We get a copybook example here of “vox populism”,[3] the version of populism that is centered around manufactured representations of the “voice of the people”: first, I teach you how to talk like me, after which I can claim to talk like you, to represent your voice and turn it into a political, “democratic” program. And virality becomes a crucial infrastructure for such vox populism: look at the many thousands who retweet my words. Surely I must be a democratic politician. I must be the most democratic one ever.

Notes

[1] Ico Maly, Nieuw Rechts. Berchem: EPO 2018: 51. I am grateful to Ico Maly, Sjaak Kroon and Rob Moore for inspiration and comments on an earlier version of this text.

[2] See e.g. Jan Blommaert, Dialogues with Ethnography. Bristol: Multilingual Matters 2018, chapter 4.

[3] Jan Blommaert, Ik Stel Vast. Berchem: EPO 2001. Ico Maly, Nieuw Rechts. Berchem: EPO 2018.